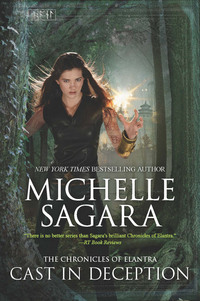

Cast In Deception

“There was a fight?”

Caitlin did not reply.

Marcus did, in a fashion. His low growl filled the office, which was otherwise unnaturally silent. Silence was never good, here. Kaylin glanced at Bellusdeo, whose eyes remained a remarkable gold as she inclined her chin in Kaylin’s direction.

Kaylin then went to stand at attention in front of the sergeant’s desk. Hardwoods, she decided, were good. They didn’t scratch as easily, and it was clear from the surface of the desk that Marcus had been working at making a few gouges.

“You are to meet your partner and head—immediately—to the East Warren.”

Kaylin, who had expected the word “Elani” to crawl out from between the folds of a growl, blinked. The East Warrens, as the area was colloquially called, was a Hawk beat; its boundary ended at the Ablayne, and the enterprising fool who chose to cross it ended up in one of the fiefs. Kaylin’s geography was sketchy at best; she mostly knew what she’d walked across. She hadn’t walked into that fief.

Bellusdeo, however, had a strong interest in the fiefs—or, more accurately, the Towers that stood at their centers. “The East Warrens?” Her eyes had lost their gold, but at least that made sense; Marcus’s eyes were red. His facial fur, however, hadn’t jumped up two inches; it had settled. He looked sleek, his upper fangs more exposed than they usually were, his claws extended.

He wanted to tell Bellusdeo to get lost, except with ruder words. And he wanted to tell Kaylin to go home. She felt some sympathy for this, because she wanted to tell Bellusdeo to go home. The East Warrens were not Elani street in any way; they were vastly more dangerous. It was not a beat given the groundhawks of the mortal variety. The Aerians could fly patrol over the streets, but at a safe enough height crossbows wouldn’t be an issue.

No, it was a Barrani beat.

Marcus, for whom low growling had replaced all sound of breath, waited, daring Kaylin to argue. She wasn’t stupid. In his current mood, she’d agree that black was the new pink if that’s what he demanded, and consider herself lucky. Enraged Leontine seemed far more dangerous than a strolling walk through some of the city’s poorer streets. A Dragon would certainly make that patrol safer.

Until the Emperor heard about it.

“May I ask,” Bellusdeo began.

“No.”

“—if this has something to do with the fief of Candallar?”

Marcus said nothing. He growled, but didn’t bother with words. Unfortunately, he was facing a Dragon—a Dragon who hadn’t been forced to swear an oath of allegiance to the Emperor, whose laws the Hawks served. And any attempt to rip out her throat or tear off her arm—or leg—was going to be unsuccessful, in the best case. In the worst case—and given Marcus’s mood, worst was a distinct possibility—the office would be reduced to charred wreckage. Charred, broken wreckage.

And that was above her pay grade.

Bellusdeo, however, folded her arms and looked down at the sergeant, her eyes narrowed. They stared at each other for three long, half-held breaths. It was, to Kaylin’s surprise, Marcus who looked away first—but by the time he did, his eyes had shaded to a much safer orange.

“Yes.”

“And does the fief of Candallar have something to do with the current mood of the office?”

“I don’t discuss rostering issues with anyone who doesn’t outrank me.”

Bellusdeo’s smile was gem-like: hard enough to cut, but bright anyway. Kaylin wanted to leave to find out what had happened, but knew better. She waited. Marcus finally dismissed her, although he didn’t bother to look in her direction. Bellusdeo, however, did not follow.

* * *

“What happened?” Kaylin asked, keeping her voice as low as she could. Marcus’s hearing was good, but he was unlikely to hear her when she was in Hanson’s office. Hanson was the choke-point for the Hawklord’s time; he was like, and unlike, Caitlin. This morning, the dissimilarities were stronger.

“It is not a going to be a good day,” he told Kaylin. “The Hawklord hasn’t demanded your attendance—which is about as much luck as you’re likely to have in the near future. If I were you, I’d remember that you’re a private. Whatever is happening, it is not your problem.”

“Did I mention that Teela and Tain are coming to live with me?”

“Fine. It is your problem. Your problems, however, are not my problem.”

“East Warrens is a Barrani beat.”

“You don’t say.”

“Bellusdeo is coming with me, wherever I happen to be assigned.”

Hanson grimaced; she could practically hear the lines around his mouth crack. “Emperor’s problem,” he finally said. But he knew that if something happened to Bellusdeo, it would be everyone’s problem. And in this case “everyone’s” problem was a matter for the Hawklord. Which, of course, would become Hanson’s problem. “There was an altercation this morning between two of the Barrani Hawks.”

“Go on.”

“In general, Corporal Danelle handles difficulties between the Barrani Hawks. She is not the only corporal among their number, but her word carries weight with the Barrani for entirely extralegal reasons. The altercation occurred before her arrival; it was considered severe enough that she booked the West Room in which to resolve the difficulties.”

Kaylin nodded. In and of itself, this was business as usual, although Barrani altercations were on the wrong side of “intense.”

“The altercation was between Corporals Tagraine and Canatel.”

She frowned. They were partners. While altercations between Barrani could be intense, in general they had greater respect for—or at least care for—their beat partners. “What set them off?”

“The office was largely empty when the altercation occurred. Barrani don’t need sleep; they usually arrive early. Today, they arrived early. Teela did not.” He raised a brow, as if expecting that Teela’s tardiness—for a Barrani—was somehow Kaylin’s fault. “She entered the office as the altercation was in progress, broke it up and booked the West Room.”

Kaylin had heard nothing that would justify removal of Barrani Hawks from the duty roster. “She couldn’t stop the altercation.” It wasn’t a question.

Hanson bowed his head for a long minute. When he raised it again, he looked exhausted. “It appears that the altercation between Tagraine and Canatel was a fabrication. The purpose of the altercation was to separate the rest of the office from the Barrani.”

She froze then. The only good reason to do that was the laws of exemption: if only Barrani were involved, the Imperial Laws took a back seat to the caste court laws. A Barrani confrontation in the normal office could not be guaranteed not to cause extraracial collateral damage—and that would void the laws of exemption entirely. The implications of that...were not good.

She thought of the morning’s events, the morning’s arguments, the fact that the cohort were coming to stay with Helen, and Tain’s comment—cut off angrily by Teela—that Teela had already been under “pressure.” The Barrani definition of pressure.

“Something happened to Teela.”

“Something,” Hanson said, exhaling, “almost happened to Teela. She survived. One of the two would-be assassins did not.”

“Tagraine and Canatel?”

Hanson nodded.

“The survivor is in the infirmary that we’re not allowed to visit by order of Moran, unless we want to join him.”

He nodded again. “The High Court has been on the mirror network, demanding an explanation. The East Warrens may, or may not, have been involved with the altercation in some subtle way. Therefore the Barrani are off that beat.” He exhaled. “They are off their beats until some of the issues are resolved.”

“Meaning investigations are ongoing.” It was a catch phrase used in place of hells if I know.

“Meaning exactly that.”

“How, exactly, did the High Court even know?”

“Apparently they were informed.”

“By who?”

“Oddly enough, no one in the office even thought of asking that question. I’m sure if someone had, we’d have that information in our hands by now and everything would be resolved.” The sarcasm in Hanson’s voice should have been lethal; it was embarrassing instead.

“The Emperor’s going to reduce me to ash if anything happens in the warrens.”

“Figure out a way to survive a lot of fire then,” Hanson replied. It was the warrens; if was not precisely the right word. It was simply the hopeful one.

* * *

“The warrens are okay,” Kaylin told Bellusdeo on the way to said warrens. Severn said nothing. “They’re nowhere near as bad as the fiefs. They’re more crowded than the rest of the city, and more run-down. But: no Ferals.”

“I have no fear of Ferals,” Bellusdeo replied. “And before you warn me of all the other dangers, please remember I’m a Dragon. A prickly Dragon.”

“If it helps, this is considered a Barrani beat.”

“Because no one is stupid enough to think a few underfed thugs present a danger to the Barrani, of course.” Her chilly tone was a warning. She considered Dragons to be stronger than Barrani, and any implication to the contrary was not going to be well received. “Do yourself a rather large favor and worry about your own survival.”

She wasn’t worried about Bellusdeo; she was worried about the Emperor. She couldn’t point this out if she didn’t want to add to the hostility between the two Dragons. Since the Emperor had come to dinner at Kaylin’s house, there’d been something close to peace between them—but it was a peace between previously warring nations. It was fragile.

“Besides, I think your assignment in the warrens was a deliberate choice.”

“Oh?”

“I go where you go, with Imperial permission.”

“You think they’re expecting real trouble? No wonder Marcus was in a mood.”

“Oh, I think your sergeant’s mood had a lot to do with the Barrani unrest. He’s a sergeant. He expects everyone under him to operate under the same rules.” Bellusdeo smiled fondly. “It’s almost nostalgic.”

“You had to deal with sergeants?”

“Or their equivalents, yes. But never from beneath them.” She shook herself. “He is fond of you, of course, which is why you come in for more of his public displeasure than the average new recruit. He can’t afford to show favoritism. It bleeds solidarity from the ranks. If he’s fond of you—and he is, no one could miss that—and he treats you the way he does, it means no one is safe.” She wrinkled her nose. “I take it this is also where the tanneries are.”

* * *

Kaylin did not detest the warren. She didn’t feel the need to make excuses for the people who lived here; life had already done that. But she knew theft from the inside out. Knew that she’d been good enough not to get caught often. She needed to eat, same as anyone, and if there was no way to do that legitimately, she’d made other choices. She wasn’t proud of them, but she wasn’t humiliated by them, either.

She understood that once you started, crime became another tool, another way to survive. That you could want a better life, dream of it, of being a better person, and it didn’t matter. Dreams didn’t fill a stomach. But the warrens were on this side of the Ablayne. They were subject to the Emperor’s Law. The worst excess of human behaviors was curbed here. It wasn’t like the fiefs.

She knew that the tabard she wore put a wall between her and the warren’s residents. But at least it was the East Warrens, not the south.

“Power,” Bellusdeo said, “is always interesting. It is not an absolute, with few exceptions.”

“Exceptions?”

“The Eternal Emperor would be one of them. But he is considered out of reach. His position is not visibly contested in any way. People gather. It’s what people do.”

“Dragons don’t.”

“No. But Dragons have hoards, and hoards can make a Dragon dangerously unstable if they are not prepared for it. We do not make friends the way mortals do.”

“Or the way Barrani do?”

“Or the way Barrani do, no. We have not found there is strength in numbers, except perhaps in the case of war. And even then, it is questionable. I ruled. In any gathering of mortals, at any station of life, there is always a question of power. Or perhaps hierarchy. Even in the fiefs, where one could arguably say there is little true power, people struggle for position. People kill for it, one way or the other.”

“That doesn’t make humanity sound all that appealing.”

The Dragon smiled. “If that was all that humanity contained, perhaps it would be unappealing. The power games of most mortals makes no material difference to my life. But no, power itself is inert. People want it for different reasons. In the warrens—as in your fiefs—they want power because it is tied to survival. But so, too, family, kin, clan. To belong to a group is to gain a negotiable safety from it. It is why gangs clash. It is why reprisals exist.

“I would imagine the warrens are no different from the fiefs. Tell me, have you lost many Hawks to the warrens?”

Kaylin glanced at Severn. It was Severn who answered. “Yes. Not, however, since Barrani joined the force. Aerian patrols were also successful in preserving lives, but they were not considered as effective at deterring crime.”

“And the Barrani themselves are trusted not to add to the crime?”

“They have been,” Severn replied. “Teela, however, has been crucial to their performance.”

“And someone tried to kill her this morning.”

3

Each beat had its own route. Even Elani. Those routes, however, were considered by most beat Hawks to be general guidelines, and deviation from the suggested norm was not career-threatening. Flexibility was a necessity in the life of a beat Hawk, something that the higher-ups did understand, except when it came to quartermasters and uniforms.

Kaylin knew the warrens because she had come here with Teela and Tain before she had been given a rank and a uniform of her own.

Being with Barrani, and not hiding from them, had been a novel experience. She understood why people in the warrens vanished from visible windows or door frames as the two Hawks walked by. She also understood that the very young, very stupid, or very ambitious could—and occasionally did—attempt to take Hawks down.

It was the reason this was considered a Barrani beat. If the gangs felt they were equal to two officers with tabards, the equation changed markedly when the people who were wearing the tabards were Immortal. The gangs here had lived their lives in the maze of buildings and compromises that were the warrens. They could be forgiven for assuming the law was irrelevant, because in most obvious ways in their limited experience, it was.

It had been both irrelevant and a daydream in the fiefs of Kaylin’s youth, and at least these streets didn’t have Ferals literally devouring the unwary.

But...was that really any better? She wanted to slap herself for even thinking it. Clearly she’d been too comfortable, too safe, for too long. The Ferals were death. You had a hope of negotiating with anything else.

“You’re thinking, again.”

“Ferals,” Kaylin told the Dragon. “We were more terrified of Ferals than almost anything else.” Small and squawky snorted dismissively. Bellusdeo didn’t bother, but it was clear she felt the same.

“That wasn’t a terrified face.”

“It’s just...they weren’t personal. They weren’t plotting against us. They wanted one thing: to eat us. We wanted one thing: to avoid them. The cost for failure was high, but...it wasn’t personal. Does that make sense?”

“Yes. Why are you thinking of that here?”

“Because the East Warrens are the closest the city comes to the fiefs I grew up in.”

Bellusdeo frowned. “I would like a word with your Emperor.”

“Have several. But before you do, are you implying that your city didn’t have warrens?”

Bellusdeo was silent for several steps. “No. I couldn’t realistically imply that. Some of my best soldiers, however, probably came out of my version of your warrens.” She smiled and added, “We’re being followed.”

“Oh, probably.”

“Will they attack us?”

“They might. They’re used to seeing Barrani in these tabards; the Barrani have been doing this beat for a long time, now. Seeing normal mortals—”

Bellusdeo coughed.

“They can’t see the color of your eyes from here, and you don’t look Barrani at a distance. Even if they could, I doubt over half would realize what the eye color meant. For obvious reasons, there aren’t a lot of Dragons randomly wandering the streets. If they do attack, though, going full-on Dragon would probably be the fastest way to end the fight.”

“I thought that was illegal.”

“You’ve always gotten away with it before.”

“Kaylin.”

She stopped talking at the sound of Severn’s voice. She didn’t, however, stop walking. She didn’t even glance in his direction. She knew where he was, knew how far away, knew how ready he was for a fight. “Where?”

“The old town hall.”

She glanced down the street toward the tallest building in the warren. It stood at the edge of this particular beat, but it had, some indeterminate length of time ago, been a rallying point in a besieged city. It was called the town hall because historical rumor suggested it had been built for that purpose. Whether it had seen any use in that capacity was an entirely different question.

Her small dragon, however, drew himself into the seated posture that implied he was ready for a fight. Or a bellow of outrage. Since she hadn’t done anything to warrant the latter, she tensed, but didn’t break her slow, steady stride.

Not until a familiar voice said, “This is not the place for you.”

Bellusdeo came to an immediate stop. Golden eyes reddened significantly into the orange that was anger, worry or fear—and Bellusdeo was not afraid of the owner of that voice. “What,” she said, in her icy, regal queen tone, “are you doing here?”

Mandoran, however, failed to materialize.

The small dragon squawked and then lifted a wing to cover Kaylin’s eyes. The wing was translucent, of course, but looking through it often revealed hidden things. Or worse. Mandoran wasn’t so much standing in the street as drifting above it.

“What are you doing here?” Kaylin demanded, repeating the gold Dragon’s words. Because Bellusdeo had stopped walking, she had come to a stop as well, the rhythm of patrol abruptly broken.

“Teela found out that you’d been sent to the East Warrens on patrol.”

“Yes. And?”

Mandoran made a face. “She doesn’t want you in the East Warrens. But it’s not actually you she’s worried about.”

Mandoran, Kaylin decided, was an idiot. Had she been in possession of his True Name, she’d be shouting at the top of her lungs in his figurative ears. His wince made clear that someone in his cohort—likely Teela—had had the same thought.

Sadly, Bellusdeo wasn’t as oblivious as Mandoran. “She couldn’t possibly be worried about me.”

“Maggaron’s been sulking for weeks now because he’s not allowed to accompany you—and you know how he hates being left out of a fight.”

Bellusdeo’s brows rose, briefly, in Kaylin’s direction—but to do that, she had to break her glare. “Ask Teela how political this is.”

Mandoran, unlike most of the Barrani she had known before the cohort, was terrible at lying. He didn’t try. “She says you’re likely to survive, and the miscreant she’s worried about—the soon-to-be possible miscreant—would take heat for any attack against you in the High Court. Problem is, he’s not part of the High Court, and hasn’t been for some time.”

“You have an outcaste living in the warrens?” At Mandoran’s expression, Bellusdeo added, “It wouldn’t be the first time it’s happened.”

“This would not be my idea of a safe hiding place.” Mandoran’s grimace was heavy with disgust; it was also brief. He turned to Kaylin. “Teela wants you out of the warrens.”

“Marcus doesn’t. And you can tell her I said so.”

“I won’t repeat what she just said.”

“Why not? I’ve heard it all before.”

“Yes, but the Dragon probably hasn’t, and you know the Emperor’s just going to blame you if she starts using that kind of language.” For a moment, his expression looked normal but his color was entirely off. His hair seemed almost white, his skin, blue. And his eyes were not Barrani colored at all.

The small dragon squawked, and Mandoran cursed. He turned toward the old town hall. Kaylin tracked the direction of his gaze with little effort.

She froze.

Standing at the peak of the decrepit tower roof was a Barrani.

* * *

Unlike Mandoran’s, his coloring was more or less the norm for Barrani: his hair was black, his skin ivory. At this distance, his eyes couldn’t clearly be seen, but Kaylin would have bet her own money that they were Barrani blue. She hadn’t managed to contain her surprise enough to look away, and although she couldn’t see the color of his eyes, she saw the subtle shift in their shape.

He was invisible, and had expected to remain so. She had seen him. Math had never been Kaylin’s strong suit, but even she could handle one plus one.

“Time to move. Move.”

Severn was armed, but had not yet unwound his weapon chain; not even in the fiefs did he fully arm himself unless it was night. She headed into the nearest narrow alley to break the line of sight, and everyone except Mandoran followed.

She practically spit his name in a whisper that would have been a hiss had his name had any sibilants.

“He can’t see me.”

“Don’t be so certain of that.”

“Even if I were visible, I wouldn’t be too worried. It’s the Dragon he’s going to be aiming for.”

“He can try,” the Dragon snapped. It obviously annoyed her to have to run and hide from Barrani. Then again, it often annoyed her to have to run, period. She was a Dragon.

“Are all Dragons like this?” Mandoran asked, as if he did have Kaylin’s True Name, and had heard the thought.

“Not the time for this,” Kaylin snapped back. “What is he doing?”

“Moving.”

“Coming down?”

“Yes. In case you’re worried, he’s not using the stairs.”

“Given the rest of the exterior, I doubt the stairs would support his weight.”

Mandoran swore.

“What’s happening?”

“He can, apparently, see me.”

Bellusdeo snorted smoke.

“I’m going to head back home now, while Teela is only enraged. She can’t leave the office if she wants to retain the tabard—but she’s considering it anyway.” True to his word, Mandoran faded from sight. Kaylin didn’t see him leave, but knew the moment he was no longer present.

“I’m going to strangle Mandoran,” Bellusdeo said, in a soft voice. “The minute we get home. I’m going to throttle the life out of him.”

“Fire would be faster,” Kaylin observed. She had retreated—they had all retreated—to the middle of the alley; there were walls to either side, and the windows they possessed weren’t large enough to cause tactical problems.

“Exactly.”

Severn had finished unwinding the chain, although this was not the place to make full use of it; the alley was too narrow. All of the alleys in the warrens were. “He’s coming.”

Kaylin nodded, her expression shifting. The familiar kept one wing across both of her eyes. She shook her head. “Go to Bellusdeo,” she told the translucent, winged creature. “Now.”

“I don’t need his protection—”

“No, I do. If anything happens to me, I’ll recover. Unless I’m dead. If anything happens to you, I’ll only wish I was dead. Probably forever.” She grimaced.

Severn said, “Magic?”

She nodded. Her skin was beginning to tingle. Tingling was not painful, but in general, it didn’t stop there. Kaylin’s allergy to magic—if allergy was the wrong word, it was the one she used anyway—made certain types of magic actively painful. It was why she hated doorwards and other modern security features. Invisibility—and there were whole libraries about how it worked, all jealously guarded by mages—was not a small magic. It wasn’t considered nearly as insignificant as a doorward.