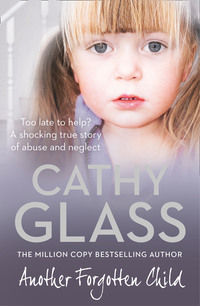

Another Forgotten Child

At lunchtime Jill telephoned and asked if I’d heard anything from Kristen. I hadn’t, so we assumed the case was still in court. An hour later Kristen phoned and said she’d just come out of court and the judge had granted the care order, which was clearly a relief. Kristen said she and her colleague, Laura, were on their way to Hayward school to collect Aimee. ‘Susan, Aimee’s mother, was very upset in court,’ Kristen said. ‘And her barrister was good, so I had to agree to let Susan see Aimee for half an hour at the end of school to say goodbye.’

‘All right,’ I said. ‘See you later.’ I put down the phone and thought of Susan going to school to say goodbye to her daughter.

I felt sorry for her, as I did for many of the parents whose children I fostered, for none of them started life bad with the intention of failing and then losing their children. I guessed life had been cruel to Susan, just as it had to Aimee.

Chapter Three

A Challenge

Despite all the years I’d been fostering I still felt nervous when anticipating the arrival of a new child. Will the child like me? Will I be able to help the child come to terms with their suffering and separation from home? Will I be able to cope with the child’s needs? Or will this be the one child I can’t help? Once the child arrives there is so much to do that there isn’t time for worrying, and I simply get on with it. But on that Thursday afternoon while I waited for Aimee to arrive, which I calculated would be between 4.30 and 5.00 p.m., my stomach churned, and all manner of thoughts plagued me so that I couldn’t settle to anything. Jill had phoned to say she’d been called to an emergency so wouldn’t be able to be with me for moral support when Aimee was placed. I’d reassured her I’d be all right.

Paula arrived home from school at four o’clock and, having had a drink and a snack, went to her room to unwind before starting her homework; Lucy wouldn’t be home until about 5.30. My anxieties increased until at 4.40 the doorbell rang. With a mixture of trepidation and relief that Aimee had finally arrived, I went to answer it.

‘Hello,’ I said brightly, with a big smile that belied my nerves. ‘Good to see you.’ There were two social workers, whom I took to be Kristen and her colleague Laura, and they stood either side of Aimee, who carried a plastic carrier bag. ‘I’m Cathy. Do come in.’ I smiled.

It was clear who thought she was in charge, for, elbowing the social workers out of the way, Aimee stepped confidently into the hall and then stood looking at me expectantly.

The social workers followed. ‘Hello, Cathy,’ they said and introduced themselves.

‘Shall we leave our shoes here?’ Kristen said thoughtfully, slipping off her shoes, having seen ours paired in the hall.

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘And I’ll hang your coats on the hall stand.’

As Kristen and Laura took off their shoes and coats I looked at Aimee, who was doing neither. ‘Shall we leave your shoes and coat here?’ I said encouragingly.

‘No. Not taking ’em off,’ Aimee said, jutting out her chin in defiance. ‘And you can’t make me.’ My fault, I thought, for giving her a choice. What I should have said was: ‘Would you like to take off your coat first or your shoes?’ It’s a technique called ‘the closed choice’ and would have resulted in action rather than refusal.

‘No problem,’ I said easily. ‘You can do it later.’

‘Not taking ’em off at all,’ Aimee said challengingly. The two social workers looked at me and then raised their eyes.

‘You can keep your shoes and coat on for now,’ I said, aware I needed to be seen to be in charge. ‘And we’ll take them off later. Come on through.’ Before Aimee could give me another refusal I turned and led the way down the hall and into the sitting room. My thoughts went again to Jodie. Although Aimee was the same age as Jodie, with similar blonde hair and grey-blue eyes, she wasn’t so badly overweight and also seemed more astute. I knew I would need my wits about me in order to gain her cooperation.

In the sitting room Aimee plonked herself in the middle of the sofa, which left the two social workers to squeeze themselves in either side of her. ‘This is nice,’ Aimee said, running her eyes around the room. ‘It ain’t like this at my house. My ’ouse is a pigsty.’ I smiled sadly at her heartfelt and innocent comparison – she was simply stating it as she saw it.

‘No,’ Kristen agreed, seizing the chance to demonstrate what an improvement coming into care was. ‘Cathy’s house is clean and warm and has lots of nice furniture. You’ll have your own room here – we’ll see it soon. And there’ll always be plenty of food and hot water.’ All of which I assumed had been missing from Aimee’s house.

‘It’s nice, but it ain’t me home,’ Aimee said.

‘It will be for now,’ Laura put in.

‘No it won’t,’ Aimee said, louder, turning to Laura and jutting out her chin. ‘Me home’s with me mother and neither you nor your bleeding lawyers can change that.’

Kristen and Laura both looked at me. ‘I can guess where that’s come from,’ Kristen said. I nodded. It was a phrase an adult would have used, not an eight-year-old child, so I assumed Aimee was repeating something her mother had said.

‘Cathy will be taking you to school and collecting you,’ Kristen continued, unperturbed. ‘And tomorrow you’ll be able to see your mother after school.’ Then, looking at me, Kristen said: ‘I’ll speak to you later about contact arrangements.’

‘OK,’ I said. Then I offered them a drink, as I hadn’t done so before.

‘No, I’m fine, thanks,’ Kristen said. ‘We’ll settle Aimee and then get back to the office.’ Laura agreed.

‘What about you, Aimee?’ I said. ‘Would you like a drink?’

She shook her head, more interested in the objects in the room, which she was gazing at in awe, like a child in a toyshop. My sitting room was nothing special, but it clearly was to Aimee, who seemed mesmerized by the framed photographs on the walls, the potted plants, ornaments, etc. like those that adorn most sitting rooms.

‘Aimee has one bag with her,’ Kristen said. ‘It’s in the hall.’ I nodded. ‘We’ll try to get some more of her things when Mum has calmed down, but I’m not sure how much use they’ll be.’ I nodded again, as I understood what she meant. If the clothes Aimee wore now were representative of the rest of her clothes, the others were likely to be suitable for the ragbag. The jacket she’d refused to take off was far too small, dirty and badly worn; the faded black jogging bottoms were too short and badly stained; and her plastic trainers had split at both toes, so that her socks poked through. I couldn’t remember the last time I’d seen a child so poorly dressed.

‘Is she in her school uniform?’ I asked, mindful that Aimee had come to me straight from school.

‘What there is of it,’ Kristen said. ‘You’ll need to buy her a whole new uniform. I’ll arrange for you to have the initial clothing allowance.’ This allowance – approximately £80 – is a payment made to foster carers when a child arrives with nothing and needs a whole new wardrobe. It is often weeks before the money is paid and it only goes some way towards the clothes a child needs, but at least it is something.

‘Thank you,’ I said.

‘Is there somewhere private where we can go to talk?’ Kristen said to me. ‘Laura could stay here with Aimee.’

‘Of course,’ I said, standing. ‘We can go in the front room. There are some games over there,’ I said to Aimee and Laura, pointing to the boxes of games I’d brought in.

Laura stood and went over to select a game while Aimee remained on the sofa, studying its fabric as though she’d never seen anything like it before. Then she began struggling out of her jacket. ‘It’s bleeding hot in ’ere,’ she said. ‘I’m gonna take me coat off.’

‘Good choice,’ I said, throwing her a smile.

Kristen took some papers from her briefcase and as we left the room we heard Laura suggest to Aimee they do a jigsaw together and Aimee ask what a jigsaw was.

‘Aimee is eight,’ I said quietly to Kristen in the hall. ‘And she doesn’t know what a jigsaw is?’

‘It doesn’t surprise me,’ Kristen said. ‘She’s been so neglected. There were never any toys at her mother’s flat, so Aimee watched television all day and night. Susan said the toys were at Aimee’s father’s flat but he wouldn’t let me in, so I could never substantiate that. I doubt there were toys there, though. All their money went on drugs.’

Once we were in the front room with the door closed Kristen confided that Aimee’s was one of the worse cases of neglect she’d ever come across, and repeated that she couldn’t understand why she hadn’t been removed from home sooner. Then she said again that Aimee had very bad head lice, so my family and I should be careful not to catch them.

‘I’ll treat her hair tonight,’ I said. ‘I have a bottle of lotion.’

‘Good,’ Kristen said. ‘She needs a bath as well. She smells something awful.’

I nodded, for I had noticed as she’d walked in. ‘I’ll do that as well before she goes to bed.’

‘You know Aimee used to kick and bite her mother when she tried to wash her?’ Kristen reminded me.

‘Yes, I know. I read it in the referral.’

‘There’s a high level of contact with her mother,’ Kristen said, moving on. ‘Face-to-face contact will be supervised at the family centre and it will take place after school on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. There will be telephone contact every night they don’t see each other, including weekends. Can you monitor the phone contact, please, on speakerphone?’

‘Yes,’ I said. This was something I was often asked to do. ‘So is the care plan eventually to return Aimee home?’ I asked. That was the most likely explanation for the very high level of contact – so that the bond between Aimee and her mother would be maintained for when Aimee was eventually rehabilitated at home.

‘Good grief! No!’ Kristen exclaimed, shocked. ‘There’s no chance of Aimee being returned home. Her mother has been given enough chances to sort herself out in the past. The care plan is to try to find Aimee an adoptive home or, failing that, a long-term foster placement.’

‘So why is there so much contact?’ I asked, puzzled. ‘It seems cruel if there’s no chance of her going home.’

‘Susan’s barrister pushed for it in court and there was a good chance that if we hadn’t agreed the judge wouldn’t have granted us the care order.’

‘What?’ I asked, amazed. ‘With this level of neglect?’

‘I know, it’s ludicrous.’ Kristen sighed. ‘But the threshold for granting care orders is so high now that children are being left at home for longer than they should.’

Not for the first time I thought how badly the whole child protection and care system needed reviewing and revising. While no one wants to see a family split, early intervention can give a child another chance at life. By the age of eight most of the damage is done and it is very difficult to undo.

‘As mentioned in the referral,’ Kristen continued, checking the essential information forms she’d taken from her briefcase, ‘Aimee wets the bed.’

‘I’ve put a protective cover on the mattress,’ I said. ‘It’s not a problem.’

‘Good. It was at home. The mattress Aimee and her mother slept on in the lounge stank of urine. It was disgusting and you could smell it as soon as you walked into the flat. Now, as you know, Aimee needs firm boundaries and routine,’ Kristen continued. ‘There were none at home. And as I mentioned on the phone Susan is very good at making allegations and complaints against foster carers, so be careful. She seems to think that if she gets her children moved enough times they will eventually be returned to her, but of course it doesn’t work like that.’

‘Susan has contact with her other children?’ I asked.

‘Some. A lot of it is informal. Once kids become teenagers you can’t stop them getting on a bus and going to see their natural parents, and many of them seem to gravitate home.’ Kristen sighed again, and then, turning to the back page of the set of forms, said: ‘Can you sign this, please, and then we’ll show Aimee her room and I’ll be off.’

We both signed the relevant form which gave me the legal right to look after Aimee, and then we returned to the sitting room. Laura and Aimee were on the floor poring over a large-piece jigsaw. It was obvious Aimee hadn’t got a clue what to do and had been relying on Laura to do the puzzle for her – a puzzle for pre-school children aged two to four years.

‘Aimee,’ Kristen said brightly, ‘Cathy is going to show us your room now. Won’t that be nice?’

Aimee seemed to agree that it would be nice and hauled herself to her feet. I noticed she hadn’t got Jodie’s hyperactivity; if anything Aimee’s movements were very slow, lumbering almost. Laura stood and I led the way out of the sitting room, down the hall and upstairs. As we passed the bedrooms I said, ‘This is my daughter Paula’s bedroom. She’s seventeen. You’ll meet her later. And this is Lucy’s. She’s at work now.’

‘That’ll be nice, won’t it, Aimee?’ Lauren enthused. ‘Two grown-up girls to play with.’ I wondered if Paula had overhead this comment and what she thought of it!

Aimee didn’t say anything until we got to her room, when her face lit up. ‘Cor, this is nice. Is it all for me?’ she said with touching sincerity.

‘Yes. This is your room. Just for you,’ I said.

‘Can me mum come and stay with me? She’d like it ’ere,’ Aimee said, running her hands over the duvet on the bed.

‘No,’ Kristen said. ‘You’ll see your mum at the family centre. She won’t be able to come here.’

‘I know that,’ Aimee snapped. ‘You told me already. I ain’t thick.’

Kristen let it go but I could see how easily Aimee could change from being polite and engaging to confrontational and aggressive.

‘This is where you keep your clothes,’ I said, opening the wardrobe door, and then the drawers, to show her.

‘I won’t be needing all that,’ Aimee said. ‘I ain’t got many clothes.’

‘I’ll be buying you some,’ I said positively, with a smile.

‘No you won’t,’ Aimee said sharply. ‘That’s me mother’s job.’

‘Aimee,’ Laura said evenly, ‘while you are living here with Cathy she will buy your clothes and cook your meals, like your mother did at your house.’

‘But she didn’t,’ Aimee said, quick as a flash. ‘That why I’m in bleeding foster care. She didn’t buy me clothes. They were given to us. She didn’t take me to school, and she didn’t give me any boundaries, whatever they are. And she gave me too many biscuits, so me teeth got bad. That’s why I’m in foster care and not wiv me mum. You know that!’

I turned to stifle a smile as Aimee finished her lecture. Clearly Aimee didn’t miss much and she had such a quaint way of putting things – a mixture of child-like honesty and middle-aged weariness. I didn’t know if Aimee’s explanation of why she was in care was something that had been said to her, possibly by a social worker, or if it was a deduction Aimee had made, but it was accurate. Laura and Kristen were smiling too.

‘Is that telly mine?’ Aimee said, pointing to the small portable television on top of the chest of drawers.

‘Yes, it’s yours to use while you’re here,’ I confirmed. ‘But I limit its use. If you’ve had a good day you can watch it for a little while in bed before you go to sleep, but it’s a treat.’

‘And what if I ain’t had a good day?’ Aimee asked, turning to meet my gaze.

‘Then you won’t be watching it,’ I said clearly.

‘How you gonna stop me?’ Aimee challenged. Her eyes flashed in defiance and I saw the social workers looking at me, waiting for my reaction.

‘Very simple,’ I said. ‘I don’t turn on the television, or I remove it from the room.’

‘You can’t do that,’ Aimee said, her voice rising. ‘It ain’t allowed. I’ll tell me mum and she’ll have me moved from ’ere.’

Kristen and Laura exchanged another meaningful glance, for very likely Susan, employing tactics she’d used to disrupt the foster placements of her older children, had put this idea into her daughter’s head. I relied on my usual strategy of trying to defuse confrontation by focusing on the positive. ‘But I’m sure you won’t be losing your television time, Aimee,’ I said brightly. ‘I’ve heard you’re a good girl.’

I half expected her to say ‘No, I ain’t,’ but she didn’t. Indeed she looked quite taken aback that I’d suggested she could be good.

‘Thanks,’ she said. ‘That’s kind of ya.’

‘You’re welcome,’ I said.

I was warming to Aimee. I liked her spunky repartee when she stated her thoughts simply and directly. I liked the fact that she could look me in the eyes. So my first impression was that all was not lost and I hoped I could work with her and eventually make a difference. I was relieved and grateful that Aimee didn’t appear to have Jodie’s problems, which had resulted from horrendous sexual abuse. Yet while I now thought Aimee had little in common with Jodie, beyond hair and eye colouring, I still felt there was something that reminded me of Jodie, something I couldn’t quite put my finger on. That was until I stopped outside my bedroom and pushed open the door, so Aimee could see where I slept if she needed me in the night.

‘Do you have a man?’ she asked, peering in.

‘No, I’m divorced,’ I said.

‘So who gives you one?’ she asked with a knowing grin. It was then I knew that Aimee, like Jodie, had a sexual awareness well beyond her years: a knowledge she should not have had, and which could only have come from watching adult films or sexual abuse.

Chapter Four

‘I Want Biscuits’

I ignored Aimee’s remark, as did Kristen and Laura, and we made our way downstairs, but Aimee’s words worried me deeply, as I knew they would the social workers. Kristen and Laura returned briefly to the sitting room for their bags, and then unhooked their coats from the hall stand and slipped on their shoes. Aimee was by my side, watching them. I knew it would be difficult for her as the social workers said goodbye and left. Then reality would hit her: that she was now in foster care and living with me, not with her mother or father. For no matter how bad things are at home children usually do not want to be parted from their parents, whom they have known all their lives and love despite everything that has happened.

‘Well, goodbye then,’ Kristen said to us both.

‘Goodbye,’ Laura said, then added ‘Thank you’ to me.

‘I’ll be in touch,’ Kristen said.

‘Where you going?’ Aimee asked.

‘To our office,’ Kristen said. ‘Then home.’

‘Am I seeing me mum tonight?’

‘No, you saw her after school,’ Kristen said. ‘It’s evening now. You’ll see your mum again tomorrow after school.’

‘What’s tomorrow?’ Aimee asked, confused.

‘After one sleep,’ Laura said, using an explanation one would normally use with a much younger child.

Aimee looked blank.

‘You’ll sleep here for one night,’ Laura explained. ‘That is tonight. Then in the morning you’ll go to school and after school you will see your mum.’

Aimee nodded, although I wasn’t sure she understood. I’d explain again later. Clearly she had a poor grasp of time, well behind the understanding an average eight-year-old should have.

As the social workers left I reached for Aimee’s hand to offer comfort but she snatched it away. I noticed the social workers hadn’t tried to hug her as they’d said goodbye, as social workers often did, and I could understand why. Aimee wasn’t a child who seemed to want to be hugged, held or even touched. There was a sense of ‘keep away’ in her body language, as though an imaginary line had been drawn around her, over which you wouldn’t dare step.

As the social workers left, Lucy appeared.

‘Hi,’ I called as she came down the front garden path. ‘This is Aimee.’ Then to Aimee: ‘This is my eldest daughter, Lucy.’

‘Hello, how are you?’ Lucy asked Aimee as she came in and kissed my cheek.

Aimee shrugged. ‘Dunno.’

‘Welcome to the world of foster care,’ Lucy said brightly. ‘Your life just got so much better.’

I smiled, grateful for Lucy’s positive approach. Having come to me as a foster child herself, she knew what it felt like to be in care. But Lucy’s welcome didn’t touch Aimee and she just stared blankly at Lucy.

‘We’ll be eating a bit later tonight,’ I said to Lucy. ‘I need to get the lotion on Aimee’s hair first.’

Lucy knew what I was referring to, as she too had been plagued by head lice before coming into care, as had many of the children we’d fostered. There seems to be an ongoing epidemic of head lice in England, with many school-age children affected. And while not life-threatening they’re very unpleasant.

‘You’ll feel much better once they’re all gone,’ Lucy said to Aimee. ‘All that nasty itching will stop.’ For even in the few minutes since Lucy had come in Aimee had been scratching her head, as she had been doing on and off since arriving.

‘Me mum didn’t do it properly,’ Aimee said to Lucy. ‘The social worker gave her the bottle but it didn’t work.’

‘Don’t worry, mine always works,’ I said positively, aware that the most likely reason for the lotion not working was that its application had been interrupted by Aimee kicking her mother, as had been stated in the referral.

‘See you later, Aimee,’ Lucy said, disappearing up to her room to relax after her day at work.

‘Come on,’ I said to Aimee. ‘Let’s get rid of those nasty lice. The lotion smells but it won’t hurt you.’

As I led the way upstairs I wondered what plan B would be if Aimee refused to have the lotion applied or if she got angry, as she had done with her mother, and kicked me. Clearly I couldn’t forcibly apply the lotion, but nor could I not apply it. A bad infestation of head lice requires more than combing or brushing to get rid of it – not that she’d allowed her mother to do that either. Adopting my usual approach of being so positive that there was no room for refusal I went into the bathroom, took down the bottle of lotion, unscrewed the cap and then turned to Aimee, ready to apply the lotion.

‘Good girl, lean over the sink so it doesn’t run in your eyes,’ I said. ‘We’ll soon have you feeling better.’

There was a moment’s hesitation when Aimee looked at me, clearly deciding if she was going to do as I’d asked or not. ‘Come on, be quick,’ I encouraged. ‘Then we can have our dinner.’

There was another hesitation before Aimee took the couple of steps to the basin and bent her head over. ‘Good girl,’ I said. ‘Now stay as still as you can while I put on the lotion.’ I began separating out the hair at the back of her head and on her crown and liberally applying the lotion.

Quite often the only indication a child has head lice is the minute white eggs that are glued by the adult head lice to the root of the hair, close to the scalp, where they incubate and hatch; very rarely does one actually see head lice, as they fix themselves to the hair and camouflage themselves. But now as I massaged the lotion into Aimee’s hair and scalp head lice began appearing, drawn out by the toxic lotion. There were dozens and dozens, grouped in clusters, large adult lice that had been allowed to breed untouched for months. It was disgusting and my stomach churned. There were so many that they were crawling over each other in the thickest parts of her hair. It was one of the worst cases of head lice I’d ever seen and must have caused her untold misery. There were sores and scabs on Aimee’s scalp where she’d been scratching and had broken the skin. I thought the lotion would sting the open sores but she didn’t complain; she just stood with her head bent over the sink, quiet and still. ‘Good girl,’ I said repeatedly as I continued to apply the lotion. ‘This will feel much better.’

‘It does already,’ Aimee said, which I could appreciate. Although it would take two hours for the lotion to kill all the lice, and the lotion would need to stay on overnight to kill the eggs, many lice were already coming out and dying and therefore not biting her scalp, which must have given her considerable relief.