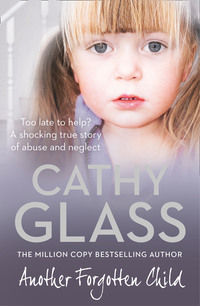

Another Forgotten Child

Before she had a chance to refuse I’d scooped up the ragged clothes and was hurrying downstairs and into the kitchen, where I threw the clothes in the washing machine. I took the pyjama top and knickers from the plastic carrier bag and put those in too. Then I added a generous measure of detergent and set the machine on a hot wash. I would have liked to have washed Aimee’s teddy bear, which was in the plastic carrier bag, but I knew Aimee would need that tonight for security. I thoroughly washed my hands and then returned to the bathroom, where Aimee had made a good attempt to dress herself. The pyjama top was on back to front but that didn’t matter.

‘Well done. Good girl.’ I smiled, and instinctively went to hug her, but she drew back.

‘Don’t you like hugs?’ I asked.

‘Not from you,’ she said defiantly. ‘You ain’t me mum.’

‘I understand. Let me know when you’d like a hug.’

‘Never!’ Aimee scowled.

Mindful that the evening was quickly passing and I would need to get Aimee up early for school the following morning, I continued with the bedtime routine. Now she was clean and in her pyjamas I gave her a new toothbrush and tube of toothpaste and told her to squeeze a little paste on to her brush and clean her teeth well. It soon became obvious that Aimee didn’t know how to take the top off the toothpaste, let alone squirt some paste on to the brush, so I did it, showing her what to do so that she’d know for next time. ‘Now give your teeth a very good clean,’ I said, handing her the toothbrush.

She put the toothbrush into her mouth, sucked off the paste and swallowed it. ‘Ahhh!’ she cried, spitting the rest into the bowl. ‘You’re trying to kill me!’

‘Aimee, love,’ I said stifling a smile, ‘you’re not supposed to eat it. Just brush it over your teeth and then spit it out. Didn’t you have toothpaste at home?’

Aimee shook her head.

‘Didn’t your mum and dad brush their teeth?’

‘Mum ain’t got many teeth,’ Aimee said. ‘And Dad takes his out and puts them in a jar.’ From which I gathered that both her parents had lost most of their teeth and her father had false teeth. Her parents were only in their mid-forties but one of the side effects of years of drug abuse is gum disease and tooth loss.

‘Do you know how to brush your teeth?’ I asked Aimee. ‘Did you brush them at home?’

Aimee shook her head.

Horrified that a child could reach the age of eight without regularly brushing their teeth, I took the toothbrush and said, ‘Open your mouth, good girl, and I’ll show you what to do.’

There was a moment’s hesitation when Aimee kept her mouth firmly and defiantly closed; then, thinking better of it – perhaps remembering her parents’ lack of teeth – she opened her mouth wide. ‘Good girl,’ I said, and I began gently brushing. Many of her back teeth were in advanced states of decay or missing. As I gently brushed Aimee’s remaining teeth, showing her how to brush, her gums bled – a sign of gum disease.

‘Did you ever see a dentist?’ I asked as I finished brushing and Aimee rinsed and then spat out.

‘Yeah. And I ain’t going back. He put a needle in me mouth so he could pull me teeth out. I’ll end up like me mum if he keeps that up.’ So that I thought at least some of Aimee’s missing teeth had been extracted by the dentist because of advanced tooth decay. The poor kid had really suffered and my anger flared at parents who could so badly neglect their daughter; but then drug-addicted parents would be more concerned with obtaining their next fix than making sure their daughter brushed her teeth.

Before we left the bathroom I told Aimee I wanted to fine-tooth comb her hair and I asked her to lean over the sink while I did it. She didn’t object and ten minutes later the white porcelain basin was covered with hundreds of dead head lice. The lotion would stay on overnight so that it could complete its job and I would wash it off in the morning. When we’d finished I praised Aimee for keeping still.

‘Will I have friends at school now?’ Aimee asked.

‘I’m sure you will. Why? Has there been a problem with your friends?’

‘I ain’t got none,’ Aimee said bluntly. ‘The other kids call me “nit head” and “smelly pants”. When I try and play with them they run away.’

‘Well, not any more,’ I said, my heart going out to her. ‘Now you’re in foster care you will always be clean and have lots of friends.’

‘Promise?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you never break a promise?’

‘Never.’

‘Cor, I’m looking forward to going to school.’

Chapter Six

‘I’ll Tell Me Mum!’

Aimee settled easily that first night. She was so pleased to be sleeping in a bed and in a room of her own that she forgot her anger at being in care. She sighed as she snuggled beneath the duvet and felt the caress of the soft clean pillow against her head.

‘This is nice,’ she said. ‘I like me bed.’

‘Good. I’m pleased. You’ll be fine in care, here with me until everything is sorted out,’ I said, and she didn’t disagree.

I had read her a bedtime story downstairs and I now tucked her into bed and reminded her I would need to wake her early in the morning so that I could wash her hair before school. I asked her if she’d like a goodnight kiss but she said she wouldn’t, so I told her to call me if she woke in the night and needed anything. Then I said goodnight and came out, closing her bedroom door as she’d asked.

When I checked on her ten minutes later she was sound asleep, lying flat on her back with her mouth slightly open and holding her teddy bear close to her chest. With her features relaxed in sleep and her blonde hair fanned out on the pillow she looked angelic, and I dearly wished I could have waved a magic wand and taken away all the bad that had happened to her and make everything all right. But realistically I knew, from what I’d seen of Aimee so far and from the referral, that it was going to be a long uphill climb to undo the harm that had been done to her before she could come close to leading a happy and fulfilling life.

Once Aimee was asleep I went downstairs, tidied the kitchen, wrote up my log notes and then watched a bit of television with Paula, while Lucy was on the computer MSNing her friends. When I asked the girls how they felt the evening had gone they agreed with me that Aimee’s behaviour hadn’t been as bad as we’d anticipated, although of course it was only the first night. Paula and I were in bed at ten o’clock and Lucy followed a little while afterwards.

I was expecting Aimee to wake in the night – her first night in a strange room – but she slept soundly and was still asleep when I went into her room to wake her for school the following morning. I’d also been expecting her to wet the bed, as the referral had stated and the social worker had confirmed she did, but she was dry.

‘Good girl, well done,’ I praised her as she climbed out of bed, yawning and stretching. ‘We’ll wash your hair before you get dressed, so go into the bathroom.’

‘Ain’t wearing those,’ Aimee said, now fully awake and pointing to the skirt and jumper I’d taken from my emergency supply and laid ready at the foot of her bed. ‘They ain’t mine!’

‘I know,’ I said, ‘but I thought you could wear those while we go to school. I’m going to buy you a new uniform from the school but you need to wear something to get there.’

‘I want me own clothes,’ Aimee demanded, her face setting defiantly.

‘No problem,’ I said lightly. ‘There they are.’ I pointed to the clothes she’d arrived in, which I’d also laid on the end of her bed, half anticipating they might be needed.

‘Me clothes are clean!’ Aimee exclaimed, astonished, as though some trickery had been done. ‘How did you do that?’

‘I washed and dried them in the machine last night,’ I said. ‘You know the washer/dryer in the kitchen?’ I added as Aimee looked blank. ‘Perhaps your mother used a launderette?’

‘What’s a laundry-net?’ Aimee asked.

‘A launderette is where you take your clothes for washing and drying if you don’t have a machine at home.’

‘We don’t go there,’ Aimee said, still eyeing the clean clothes suspiciously.’

‘Perhaps there is a washing machine at your flat.’

‘No. Me mum didn’t wash clothes.’

I thought their clothes must have been washed sometimes by someone, but it clearly wasn’t a regular occurrence, which didn’t surprise me, given the filthy state of Aimee’s clothes when she’d arrived.

‘So I’m wearing me own clothes, then?’ Aimee clarified.

‘Yes, if you wish. Then you can change when I buy your uniform at school.’

Although I would have preferred Aimee to wear the clothes I’d provided rather than the threadbare and far too small clothes she’d arrived in, I knew I could surrender this smaller point for bigger issues. Looking after a child with behavioural problems is a balancing act between what I can reasonably let go and what I have to insist on, as Aimee was about to prove.

‘Don’t want me hair washed,’ Aimee now said. ‘It’s stopped itching, so it don’t need washing.’

‘It does need washing,’ I said. ‘We have to wash out the lotion and the dead lice and eggs.’

‘No, we don’t!’ Aimee said, making a move towards her clothes.

‘You can’t go to school with your hair smelling of nit lotion,’ I said. ‘And although the lice are dead your hair is still dirty.’

‘No it ain’t!’ Aimee said again.

I wasn’t going to enter into a ‘yes it is, no it ain’t’ argument, for in this matter she needed to do as she was told. Visions of us arriving late for school on our first morning, or Aimee arriving with unwashed hair, if she didn’t cooperate, flashed through my mind. Not only would it create a bad first impression of my fostering, but it would also set a precedent that would allow Aimee to continue to do exactly what she wanted, as she had been doing at home.

‘Aimee, I need to wash your hair, love,’ I said evenly but firmly one last time.

‘No!’ Aimee said, plonking herself on the bed and folding her arms tightly across her chest.

‘Then I’m afraid you won’t be watching your television this evening, or tomorrow evening, or for the rest of the week, until I wash your hair. Now, get dressed and come down for breakfast.’ I turned and began towards the bedroom door.

Loss of television time was a sanction I’d found very effective in the past, for nearly all children like to watch some television, and Aimee was no exception. As I placed my hand on the door and was about to leave the room I heard Aimee’s voice from behind.

‘All right! You win!’ she shouted. Grabbing her clothes, she stomped past me and into the bathroom.

‘Good girl,’ I said, taking every opportunity to praise her. ‘Sensible decision.’

‘No it aint! I’m telling me mum what you did.’ Which I ignored.

Washing Aimee’s hair was no small achievement. Whereas the evening before when I’d applied the lotion I’d had Aimee’s cooperation, now she worked against me. Part of her agitation was because she wasn’t used to having her hair washed and part of it was sheer bloody mindedness – she was having to do something she didn’t want to do, although it was for her own good. She refused to lean over the bath properly, so that when I turned on the shower it was difficult to wet her hair without it running down her back; she wouldn’t keep the flannel over her face to stop the water going into her eyes; she continually moved when I asked her to stand still; and when I applied the shampoo she yelled it was cold. In fact Aimee yelled so much that eventually Lucy and Paula were driven from their bedrooms and came to see what was the matter.

‘I’m only washing her hair,’ I said defensively.

Lucy smiled and raised her eyebrows. ‘Aimee, you sound like you’re being murdered. Be quiet.’

‘Shut up,’ Aimee said rudely, raising her head and flicking soapy water everywhere. Paula groaned and the girls returned to their rooms.

‘Lucy and Paula wash their hair regularly,’ I said, hoping Aimee might see this as a good example to follow.

‘Don’t care!’ she snapped. ‘That stuff’s getting in me eyes!’

‘Well, keep your eyes closed and the flannel over your face, like I’ve told you,’ I said again.

‘And it’s in me mouth!’ Aimee shouted.

‘Keep that closed too.’ But Aimee couldn’t because she was too busy shouting and cursing at me, although she didn’t try to kick me, as the referral had stated she had her mother.

Trying to pacify Aimee as best I could, I continued with what was probably the most stressful but most necessary hair wash I’d ever given a child. As I lathered the shampoo, rinsed and lathered again, the dirty water slowly began to run clean and dead head lice finally stopped dropping into the bath.

‘All done!’ I said at last. I wasn’t sure who was more relieved. ‘Next time we’ll try washing your hair in the bath,’ I added. ‘It might be easier for you.’

‘You ain’t doing it again!’ Aimee scowled, snatching the towel from my hand and rubbing her hair.

‘Hair needs washing at least twice a week,’ I said, planting the idea so that she had time to come to terms with it.

‘No, it don’t!’ Aimee said.

I ignored this and told Aimee to go into her bedroom and I’d fetch the hairdryer and dry her hair. Throwing the towel on the bathroom floor she stomped off round the landing and into the bedroom, causing Lucy to call, ‘Be quiet, Aimee!’

‘No!’ Aimee shouted. ‘Shut up!’

I returned to Aimee’s bedroom with the hairdryer and before I switched it on I explained to Aimee that it would make a loud noise and blow hot air, for I doubted her mother owned a hairdryer. I was wrong.

‘I ain’t thick,’ Aimee said. ‘Me mum uses the hairdryer for killing me bugs.’

‘You mean she washed your hair and then dried it?’ I asked, slightly surprised, for certainly Aimee’s hair hadn’t looked as though it had been washed for weeks.

‘No,’ Aimee said. ‘Mum never washed me hair. She blew the bugs away with the dryer so they were dead.’ Which I could believe, although it was nonsense: you can’t blow away head lice, as they fasten themselves on to the hair and glue their eggs to the root shaft. But I let the point go.

Aimee moaned some more as I brushed and dried her hair, but when I’d finished, her hair shone and was quite a few shades lighter. ‘Fantastic!’ I said.

‘No it ain’t!’ Aimee said. ‘I’m telling me mum.’

‘I’m sure your mother will be very pleased,’ I said, turning her threat into a positive.

‘No she won’t,’ Aimee said. ‘She’ll report you.’ Which I ignored.

I now explained to Aimee that I wanted her to get dressed as quickly as she could and then come down for breakfast. ‘I need you downstairs by seven fifteen,’ I said, nodding at the clock on the wall. Aimee stared blankly at the clock. ‘When the big hand is here,’ I said, pointing to the three. ‘It’s five past seven now, so you have ten minutes to get dressed, which is plenty of time. What would you like for your breakfast?’

‘Biscuits.’

‘Biscuits are bad for your teeth. Toast or cereal?’

‘What’s cereal?’

‘We have cornflakes, wheat flakes, Rice Krispies or porridge.’

‘Toast.’

‘What would you like on your toast? Marmite, jam, honey or marmalade?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Sure?’

Aimee nodded.

Leaving Aimee to dress, I went downstairs and into the kitchen, where I made coffee for myself, and toast for Aimee and me. Paula and Lucy would make their own breakfasts when they came down. I lightly buttered the toast and added marmalade to mine; then I cut Aimee’s toast in half and half again so that it was easier for her to eat. Setting the plates on the table, I called upstairs to Aimee that breakfast was ready. To her credit a minute later she appeared, dressed in her old but now clean clothes. The joggers were far too small, as was her jumper, and her toes poked out of the holes in her socks, but all that would change once we’d bought her new clothes.

‘Well done,’ I said with a smile. ‘You dressed yourself very well.’ I showed Aimee to her place at the table, where her toast was waiting. ‘What would you like to drink?’ I asked. ‘Milk, juice or water?’

‘Water,’ Aimee said, sitting on the chair but too far from the table. I made a move to help her ease the chair under the table but she roughly pushed my hand away. ‘I can do it,’ she snapped.

‘All right, love, but don’t be rude. There are nice ways of saying things without being aggressive.’

‘I talk to me mum and dad like that,’ Aimee said, as though that justified her disrespect.

‘I don’t doubt it, love, but you shouldn’t. And you certainly won’t be talking to me like that.’ I said it kindly but firmly so that Aimee could see that I meant it. Teaching a child to show respect to others is crucial in putting them on the road to achieving socially acceptable and good behaviour. ‘Also, love, if you want to make friends you will need to speak to the children at school nicely too.’ Obvious to children who have been correctly brought up but not to a child from a dysfunctional background.

Aimee looked at me but didn’t say anything and I smiled again. Jumping her chair under the table until she was close enough, she took a bite of her toast and spat it out. ‘That’s disgusting,’ she cried.

‘It’s toast, as you asked,’ I said.

‘It’s got slimy stuff on it,’ Aimee said, wiping her mouth on the sleeve of her clean jumper.

‘I put a little butter on it,’ I said. ‘That’s all.’

‘What’s butter?’ Aimee asked.

I now took the butter from the fridge and showed her. She shrugged, indicating she’d never seen butter before. ‘Perhaps you had spread at home?’ I suggested.

Returning the butter to the fridge, I took out the tub of butter substitute and showed her, but Aimee shook her head. ‘We didn’t have that. I want me toast like I make it at home.’

‘All right. Tell me how you made it and I’ll do the same.’

Aimee turned to look at me and then, using her hand to gesticulate, explained: ‘I get the bread from the packet and I scratch off the green bits. That’s mould. Then I put the bread in the toaster and later it goes pop! It’s ready then. It’s hot, but it don’t have slimy stuff on it. Our toaster don’t do that. The man next door gave us the toaster. So I take me toast to the living room and I switch on the telly, only I have to have the sound on low because Mum is asleep on the mattress, and she gets angry if I wake her. Then I sit on the floor and eat me toast. I get toast and biscuits whenever I want.’

What a morning routine, I thought! I could picture Aimee waking in the morning beside her mother on the filthy mattress on the floor, then slipping out so she didn’t wake her mother, and making toast from rotting bread, which she ate dry because there was nothing to put on it. Compare Aimee, I thought, with a child from a good home. A chasm of neglect lay between them.

I made Aimee another slice of toast and gave it to her dry with the glass of water she’d asked for, but I knew I should start introducing new foods into her diet as soon as possible. She was pale, her skin was dull and her movements were lethargic, which made me suspect she might be mineral and vitamin deficient. All children who come into foster care have a medical and I would raise my concerns with the paediatrician when we saw her, and while I couldn’t give Aimee a vitamin supplement without the doctor’s or her parents’ consent, I could improve her diet.

Paula and Lucy came down to breakfast as Aimee finished eating hers.

‘Feeling better?’ Lucy asked, taking a bowl for her cereal from the cupboard.

‘No,’ Aimee scowled.

‘What’s the matter?’ Paula asked, joining Aimee at the table.

Aimee looked at the girls for a moment, then at me, and her face crumpled. ‘I want me mum,’ she cried, and burst into tears.

‘Oh, love,’ I said, immediately going to her. ‘Please don’t upset yourself. You’ll see her soon.’ I went to put my arms around her, wanting to hold and comfort her, but she drew back, so I settled for laying my hand on her arm and standing close to her.

I saw Paula’s eyes mist as Aimee sat at the table with her head in her hands and cried. ‘I want me mum. Please take me to my mum.’ For like most children, no matter how bad it has been at home, Aimee missed her mother, with whom she’d been all her life.

‘You’ll see her tonight,’ I reassured her, ‘straight after school.’

‘Don’t cry,’ Paula said, her voice faltering. ‘We’ll look after you.’

‘Better than your mother did,’ Lucy added under her breath. I frowned at her, warning her not to say any more.

‘Why can’t I see me mum now?’ Aimee asked, raising her tear-stained face. She looked so sad.

‘Because your social worker has arranged for you to see your mum tonight,’ I said. ‘And we have to do what your social worker says.’

‘Me mum didn’t do what the social worker said,’ Aimee said, oblivious to the fact that had she it would have probably helped them both.

‘I know it’s difficult to begin with,’ Lucy said, going round to stand at the other side of Aimee. ‘But it will get easier, I promise you. And doesn’t your hair feel better already? No more itchy-coos.’ Lucy lightly tickled the back of Aimee’s neck, which made Aimee laugh.

‘Good girl, let’s wipe your eyes,’ I said. I fetched a tissue from the box and went to wipe Aimee’s eyes, but she snatched the tissue from my hand and wiped them herself. Children who have been badly neglected are often very self-sufficient; they’ve had to be in order to survive.

Chapter Seven

Should Have Done More

I called goodbye to Paula and Lucy, and Aimee and I left for school at 8.00 a.m. as planned. This would allow half an hour to drive through the traffic so that we arrived at school – on the opposite side of the town – well before the start of the school day at 8.50. This morning I wanted to go into school before the other children so that I could introduce myself at reception and, I hoped, meet Aimee’s teacher or the member of staff responsible for looked-after children. All schools in England now have a designated teacher (DT) who is responsible in school for any child in care. The child is taught as normal in class but the designated teacher keeps an eye on the child, attends meetings connected with the child, and is the first point of contact for the social services, foster carer, child’s natural parents and professionals connected with the case.

As I helped Aimee into the child seat in the rear of my car she asked why she had to sit in this seat and I explained it was so that the seatbelt could be fastened securely across her to keep her safe. She had no idea how to put on the seatbelt and I showed her what to do, how to fasten it, and then I checked it was secure. I closed the car door, which was child-locked and therefore couldn’t be opened from the inside, and climbed into the driver’s seat. I started the engine and reversed off the drive. As I drove, Aimee asked many questions about the car and how I drove it, as though being in a car was a new experience for her, so that eventually I asked: ‘Aimee, have you ever been in car before?’

‘Only with the social workers yesterday,’ she said. ‘But it was dark and I couldn’t see what was happening. Mum and Dad use buses.’ Which was another indication of just how disadvantaged Aimee’s background had been. For a child in a developed country to have reached the age of eight without regularly riding in a car was incredible; I’d never come across it before. Even if a child’s parents didn’t own a car (not uncommon for children in care) the child had usually been a passenger in the car of a relative or friend’s parents; usually someone the child knew owned a car. But I believed Aimee when she said her first experience of riding in a car had been the day before, for her curiosity and questions about my car and driving it seemed to confirm this and were unstoppable: ‘What’s that blue light for?’ ‘Why’s that number moving?’ ‘Why you holding that stick?’ ‘I can hear a clicking!’ ‘There’s an orange light flashing!’ And so on and so on.