Merlin

Brakes were virtually non-existent, and Rolls had trouble with slowing down. He had graduated from Cambridge in that same year of 1898 with a degree in Mechanical and Applied Science, and started on a career in engineering. But he wasn’t a designer, more of a pioneering driver and adventurer. Lord Montagu described one jaunt:

He determined to celebrate Christmas by driving down from South Lodge to the Hendre in the Peugeot. To moderns, to embark on such an adventure in winter with primitive brakes which overheated at the least provocation appears sheer lunacy … such pneumatic tyres as were available were treadless and thus incapable of any degree of grip. Anti-freeze was unknown, and one thawed out one’s cooling system by lighting fires under the car.

On this journey Rolls had to negotiate the steep hill down the Cotswold Edge at Birdlip, which has a gradient of 1 in 6 (16 per cent).

Birdlip all but proved their Waterloo. The side-brake expired on the steepest part of the hill, while the foot-brake linkage bent under the constant pressure, and the pedal went flat to the floor, leaving the Peugeot careering downhill towards a light which appeared to be a vehicle in the road, but was fortunately a lantern in a cottage window. They narrowly missed heaps of stones but reached the foot of the hill in safety.12

(I attempted to emulate Rolls’s brakeless descent of Birdlip Hill just after writing this section. It proved impossible to descend the 1.1-mile-long hill without applying the brakes to remain within the speed limit, and on my second try a wheel hit an Edwardian-sized pothole and burst the tyre. I take my cap off to him.)

Rolls’s troubles weren’t over. The next morning as he bent down to wind the starting handle ‘the clutch pedal jammed down, and he had the humiliation of being run over by his own car. He was unhurt, but his companion was so thunderstruck that he made no attempt to arrest the Peugeot’s wild career, and it rammed a dog-cart, which Rolls had to repair before going on his way’!13

The death toll of animals killed by the new motor cars on quiet country roads was startling: Charles Rolls’s tally on just one day was two dogs, a suckling pig and four chickens. On another occasion he reported that he came around a corner with his constant-speed engine and negligible brakes only to meet a butcher’s cart. The frantic horse bolted and overturned the cart, ‘scattering various spare parts of animals about the road’.

One can imagine that the attitude of the wealthy owners did not endear them to the rustic owners of slaughtered livestock, if indeed they bothered to stop at all. Cathcart Wason, MP decried motor cars as ‘those slaughtering, stinking engines of iniquity’ and in return Lord Montagu, writing in 1966, refers to the ‘thick-headed drivers of horsed vehicles and stubborn cyclists’. His description of his rural fellow countrymen as ‘the peasantry’ is surely one of the last uses of the word in non-ironic form.

It is hard to imagine the heady excitement of motor-car driving in those pioneer days, but Kenneth Grahame captures it for us in The Wind in the Willows. Toad, Ratty and Mole are strolling down a country lane when:

… far behind them they heard a faint warning hum; like the drone of a distant bee. Glancing back, they saw a small cloud of dust, with a dark centre of energy, advancing on them at incredible speed, while from out the dust a faint ‘Poop-poop!’ wailed like an uneasy animal in pain. Hardly regarding it, they turned to resume their conversation, when in an instant (as it seemed) the peaceful scene was changed, and with a blast of wind and a whirl of sound that made them jump for the nearest ditch, it was on them! The ‘Poop-poop’ rang with a brazen shout in their ears, they had a moment’s glimpse of an interior of glittering plate-glass and rich morocco, and the magnificent motor-car, immense, breath-snatching, passionate, with its pilot tense and hugging his wheel, possessed all earth and air for the fraction of a second, flung an enveloping cloud of dust that blinded and enwrapped them utterly, and then dwindled to a speck in the far distance, changed back into a droning bee once more.

Ratty and Mole are stunned and outraged, but Toad decides at once to buy one of these machines:

They reached the carriage-drive of Toad Hall to find, as Badger had anticipated, a shiny new motor-car, of great size, painted a bright red (Toad’s favourite colour), standing in front of the house. As they neared the door it was flung open, and Mr. Toad, arrayed in goggles, cap, gaiters, and enormous overcoat, came swaggering down the steps, drawing on his gauntleted gloves.14

To Kenneth Grahame the typical motor-car owner of the time was like Toad of Toad Hall, a vulgar, spoilt, loud and boastful creature who has inherited riches from his father. Motor cars changed rural England for ever, and not for the better.

After his passion for motor cars, Rolls fell in love with ballooning, a particularly Edwardian sport involving coal gas and not hot air as a lifting medium. Rolls had his usual set of aristocratic friends with him on these jaunts. Lord Montagu said of this sport: ‘Even at its zenith, ballooning had some insurmountable limitations. A balloon could only start its voyage from the vicinity of the gas works, and thus participants in “balloon house-parties” had to desert the drawing room for the less salubrious atmosphere of the local gas company’s premises …’15

One can only begin to imagine their discomfort.

‘… One of the advantages of a feudal society was, of course, the ease with which gas companies acceded to the use of their facilities.’ Some of the toffs landed in insalubrious surroundings, too, such as Princess Vittoria de Teano, who landed next to a gypsy encampment but was kindly invited to partake of their gin. The Princess Teano was not used to slumming it:

… imagine her horror when on going to a reception given by the Duchess of Sutherland she was told that the honoured guest of the evening was Lina Cavalieri, the singer. Now all Rome knows that ‘La Cavalieri’ began her career by selling flowers at the doors of the theatres and concert halls in Rome. Donna Vittoria described how embarrassed she was; but she soon recovered her presence of mind and immediately left the house, remarking that she was not accustomed to meeting such persons. She afterward understood that King Edward, having heard of the incident, had said that she was perfectly right.16

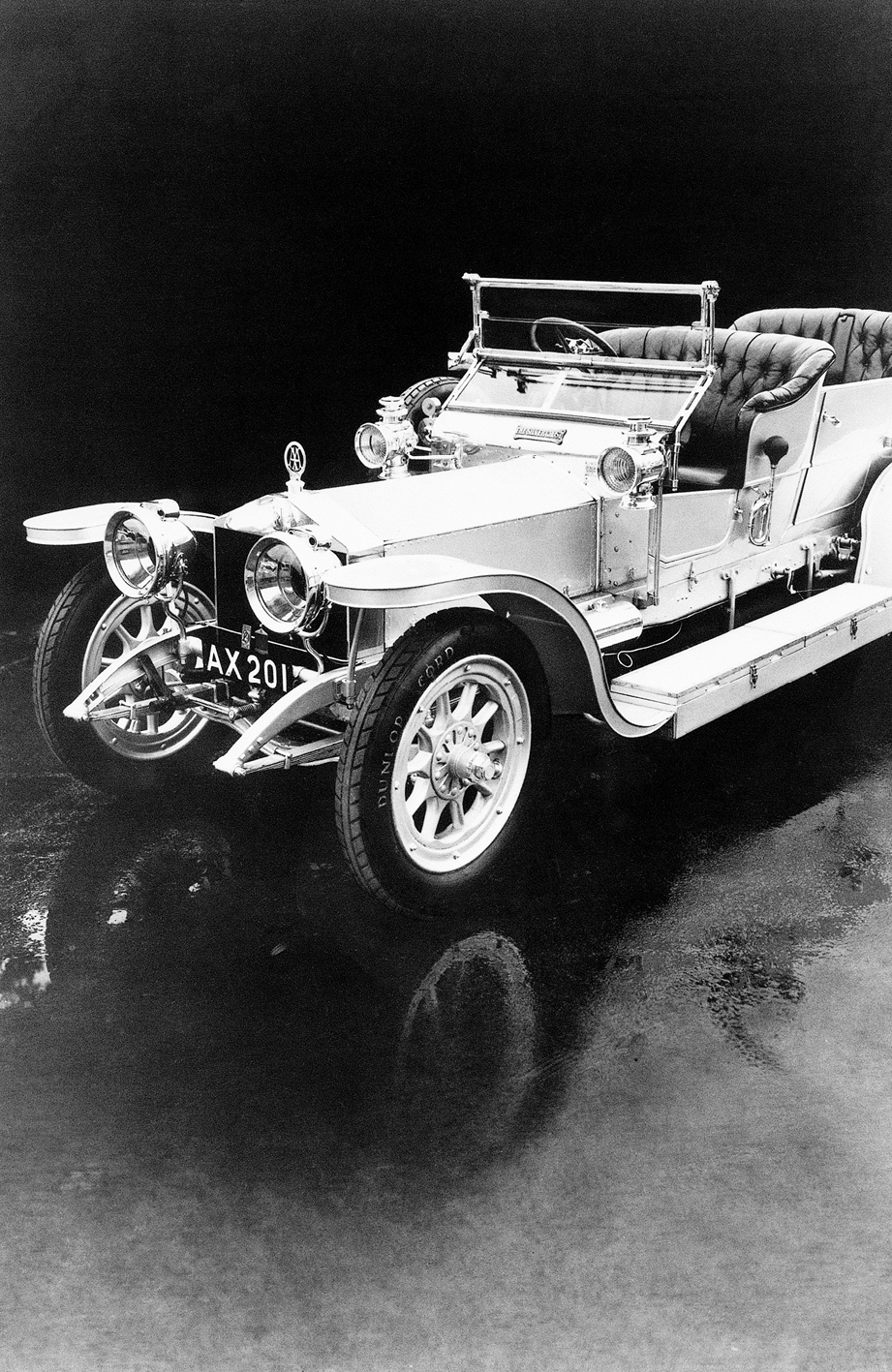

This is the milieu the Hon. C. S. Rolls inhabited, and he milked it for all it was worth. On another balloon outing the press was transported in no less a vehicle than AX 201, the original Silver Ghost, which thus received the accolade of ‘a splendid racing motor car’ from the Times newspaper. Dirty Rolls always had an eye for a sale.

Charles Rolls said to Edmunds on their train journey to Manchester that he would like his name to be synonymous with excellence, like Broadwood pianos or Chubb safes. In that he succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. When the cars are spoken of today most of the public (other than the Royce purists) refer to ‘the Rolls’. In 1902 he had started a car-sales company with Claude Johnson (later to be known as ‘the hyphen in Rolls-Royce’). The company of C. S. Rolls & Co. would be selling only the best-quality cars to the wealthy motorist. Because of the inhibiting effects of the Locomotion Acts there were few British cars of quality – perhaps only Daimler and Napier might be recognised today. Rolls therefore sold mostly French cars to his wealthy and aristocratic friends, but they weren’t particularly reliable.

One day the previous year of 1901 he was driving a French car that developed mechanical trouble. He pulled up outside a bicycle repair shop in Reading just before closing time and asked for advice and tools. The owner said he was closing up for the night and couldn’t help. However, a 16-year-old young lad who worked at the shop, one Ernest Hives, approached Rolls and asked if he could help. He got to work and soon fixed the problem. Rolls was impressed and asked the lad if he would like to come to London to be his personal mechanic. Ernest ran home to ask his mother, got permission, jumped into the car and accompanied Rolls back to his home in London. This was a fortunate meeting for the whole country, because Hives was thus serving as Rolls’s mechanic when Rolls met Royce two years later. He became Royce’s right-hand man at Derby, and as works manager he pushed through the production of the Merlin engine during the war. In 1941 he decided ‘to go all out for the gas turbine’, ensuring Rolls-Royce’s leading role in developing jet engines for civil and military aviation. He then became Chairman of Rolls-Royce Ltd and ultimately Lord Hives. Such was the curiously stratified yet meritocratic nature of English society at the time. What an extraordinary life, all contingent upon a fault in a car and a mother’s quick decision.

When Rolls met Royce he had been looking for a British-built replacement for the French-built Panhards and Peugeots he had been selling to his acquaintances. He deplored the lack of British manufacturers and was on the lookout for a suitable car. What he found at Royce’s was a revelation. Although he disliked two-cylindered engines, and had been looking for a three- or four-cylindered car, the smooth running of the two-cylindered Royce convinced him that here was a car he could sell under his own name.

The first Royce was not large by modern standards, with four solid-spoked wheels, a radiator in front with a flat top (not the later pent-roof Rolls-Royce design), a small engine, a dashboard, a round steering wheel (tiller steering had fallen out of favour) and leather bucket seats for driver and passenger.

Rolls was so enthusiastic about the Royce car that when he returned to London he is said to have hauled his business partner Claude Johnson out of bed, telling him: ‘I have found the best engineer in the world!’

Arrangements were quickly made for C. S. Rolls & Company to sell the entire output of cars from Royce Ltd. Several new models were produced, a 15 hp three-cylinder, a 20 hp four-cylinder and a 30 hp six-cylinder. This last engine proved problematic, and the solution to that problem led indirectly to the reliability and long life of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

Rolls had been insistent that a six-cylinder model was included in the Rolls-Royce range, as their rivals, especially Napier, were adding them to their ranges. D. Napier was a well-established precision-engineering company, but in the numerous uncritical hagiographies of Rolls-Royce the authors give Napier rather a raw deal. The Acton-based company had made cars before Rolls-Royce, and Charles Rolls had acted as riding mechanic on a racing Napier on the Paris–Toulouse–Paris race of 1900, buying a 50 hp model the following year. Napier seemed always to be the talented poorer cousins of Rolls-Royce, and it could be argued that they made the best British aero engines of their day in the shape of the Lion and the Sabre, but they never prospered in the long shadow of the Derby company. Napier had announced a six-cylinder engine in 1903, becoming the first manufacturer to make a commercially successful six. It was described as a ‘remarkably smooth and flexible’ car, and Napier were the first to use the expression ‘The Best Car in the World’ before Rolls-Royce used the slogan. Presumably the thought had crossed Charles Rolls’s mind that he might like to buy the Napier company, too. Or might he have wondered if he could start a company, which like Napier, could build six-cylindered cars?

And so, at Rolls’s request Henry Royce built a six-cylindered engine. It was made up of three separately cast two-cylinder units in a line above the crankshaft, which therefore had to be long. It was rather like three of Royce’s two-cylinder 10 hp engines in a row, but unlike them it kept breaking its crankshaft at a particular rate of revolutions. To his consternation three of the six-cylinder engines broke their crankshafts in early 1906.

Broken crankshafts would prove to be a problem for many makers of six-cylinder engines, including Mercedes, for whom this problem would persist for some time. Other manufacturers even had to give up making their ‘sixes’. But Henry Royce realised that the problem lay in treating the engine as three two-cylindered engines. As we saw with the Wright brothers’ six-cylindered engine, as each cylinder fired it imparted a slight twist to the crankshaft, rather like winding a spring. Like any other spring it would resent this treatment and respond by rapidly unwinding in the other direction. Unfortunately, at certain crankshaft rotational speeds this winding and unwinding could overlap with the crankshaft’s natural resonant frequency, and increase (rather like the bouncing Vauxhall we met earlier). In a six-cylindered engine these frequencies were close to the long crankshaft’s natural frequency, and at certain engine speeds these torsional vibrations set up in the long, spindly crankshaft grew worse and worse until the poor thing snapped like a carrot and the engine clanked to a stop. This would be inconvenient if fitted in a car, potentially fatal in an aeroplane.

Henry Royce in his typical fashion puzzled over this matter until he realised that if he treated the engine as two of his three-cylindered engines in mirror image he could solve the problem and achieve smooth running. Royce arranged matters so that the piston no. 1 mirrored no. 6 – both reached the top or bottom of their stroke at the same time. In the same way no. 2 mirrored no. 5, and no. 3 mirrored no. 4. The firing order was such that there was a bang every 120° of rotation. It is worth pointing out that this was nothing new: Napier had already figured out how to make a successful six-cylindered engine. But Royce’s pièce de résistance was a completely new invention, contrary to the usual view of him. It was the harmonic or vibration damper, which was a sort of flexibly mounted small flywheel attached to the front end of the crankshaft and which damped out vibrations at the critical speeds. Everything smoothed out. Royce made this crankshaft slipper (friction) vibration damper for his 1906 30 hp model; however, he didn’t patent it.17 Interestingly, the Wrights eventually offered a ‘flexible flywheel drive’ on their six, which did much the same job and suggests that the bush telegraph was working well.

When the decision was made shortly afterwards to produce just one model, the six-cylinder 40/50, Royce used the same mirror-image layout for the cylinders and made the crankshaft much beefier, with a large centre main bearing to suppress any carrot-snapping tendencies. The crankshaft had seven main bearings in total and full-pressure lubrication to all bearing surfaces. The result of all this was the world-famous smoothness and silence of the Rolls-Royce engine, which was largely due to Henry Royce’s mastery of the six-cylinder engine. It was this engine that formed the basis of the Rolls-Royce Eagle aircraft engine, doubled up to a V12 layout and enlarged to over 20 litres. In his typical style he had taken the best engine of the best car in the world and made it better, in fact good enough to be an aircraft engine.

Rolls emphasised his own name in the initial advertising. The 1905 catalogue mentioned Royce Ltd as the manufacturer of the car only on page 3: ‘Works, Manchester’, and while there were biographies and photographs of Rolls and his partner Johnson there was no mention of Henry Royce. However, Rolls did work hard, and took Royce chassis and engines to the Paris salon in December 1904. Incidentally it may surprise modern readers to learn that car manufacturers only supplied the chassis, wheels, brakes, suspension, engine and transmission. The bodies were built by traditional horse-drawn carriage builders such as Barkers, Rolls-Royce’s preferred builder. Rolls-Royce did not provide their own bodywork until early 1946.

The reviews of the 10 hp car were glowing, and the one thing they all commented on was the silent running:

… never before have I been in a car which made so little noise, vibrated so little, ran so smoothly … indeed, the conclusion I reached then and there was that the car was too silent and too ghost-like to be safe. That the engine could be set running while the car was at rest without any noise or vibration perceptible to the occupants of the car was good; that the car in motion should overtake numerous wayfarers without their giving any indication of their having heard it, so that the horn had frequently to be called into use, was almost carrying excellence too far.18

(Note that the car was described as ‘ghost-like’. This could have been the inspiration for the later Silver Ghost label.)

A gold medal was awarded at the Paris salon. The cars were a success! Royce was delighted to hear that the prospective buyers were impressed by the silent running, and worked even harder: ‘… it is only fair to add that he drove no one harder than himself. In order to solve one particularly knotty problem he did not leave the works for three days and nights, his only rest being a few hours’ sleep on a bench.’

Rolls worked at promoting the cars, too. When the headmaster of Eton retired, Rolls suggested to fellow old Etonians that a Rolls-Royce would be an appropriate leaving present. He was one of the founders of the Motor Volunteer Corps of the Army and proved the value of the newfangled motor cars to the British Army by taking the Duke of Connaught for a trial drive along the south coast. The Duke was one of Queen Victoria’s sons and Commander-in-Chief of the British land forces: once again Rolls was using his connections. This jaunt would eventually lead to the Rolls-Royce Armoured Car, as used by Lawrence of Arabia. In March 1906 Rolls-Royce was set up as a company, and Rolls travelled to the United States to promote the cars.

However, he had an ulterior motive: to meet the Wright brothers. Rolls was by then hooked on a new craze: aeroplane flying. In 1909 he bought a Wright Flyer Model A aircraft, made more than 200 flights, and by 1910 he was the best-known aviator in the country. He made arrangements with Royce to cease his day-to-day commitments to their company. Rolls then became the first man to make a non-stop double crossing of the English Channel by plane, taking 95 minutes. He became a national hero. But he crashed his Wright Flyer at Southbourne on 12 July 1910, during the first International Aviation Meeting in Great Britain, and was killed outright – the first Briton to die in a powered aircraft accident. Henry Royce was devastated.

Charles Rolls had been a visionary. He correctly forecast the universal acceptance of the car, constantly advocating a small cheap runabout for the average family. He instinctively knew how to build the prestige brand of Rolls-Royce, encouraging Royce to go upmarket with six-cylinders and the 40/50. Once the revolution of the motor car was channelled into the evolutionary progress of his Silver Ghost, he switched his attention to aeroplanes, and he planned to build an aero engine. His prophecies for the future of the aeroplane were accurate, including the techniques of aerial bombing, which was the eventual reason for the Merlin engine. His reservations on the subject of airships were proved right, and even his biographer failed to acknowledge his influence on recreational ballooning. Sceptics might scoff at his title and his privileges, but the new cult of the internal combustion engine needed a pacesetter in Britain, and Rolls was the golden boy of both motoring and aviation. Without him Royce might never have found someone to promote his little two-cylinder cars and he would probably have returned to making electric cranes. Without Rolls the Rolls-Royce Merlin probably would never have been built, and maybe the Battle of Britain never won.

Let’s give the last word on the Hon. C. S. Rolls to Lord Montagu:

In 1870, he would have been dismissed as an aristocratic dabbler, a by-product of the eccentric squirearchy; lack of funds would have frustrated him in 1930: while in our present times his birth and education alone would involve cries of ‘privilege’ from ‘the dotty left’. The age of the internal-combustion engine needed a central figure, and in Britain this central figure was Rolls.

Chapter Six

The Best Car in the World

The Rolls-Royce 40/50 ‘Silver Ghost’. Possibly the most valuable car in the world. (Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images)

The Rolls-Royce 40/50 ‘Silver Ghost’ was described as the ‘Best Car in the World’, an epithet bestowed on it by the magazine Autocar in 1907:

The running of this car at slow speeds is the smoothest thing we have experienced while for the silence the engine beneath the bonnet might be a silent sewing machine … at whatever speed this car is being driven on its direct third, there is no engine as far as sensation goes, nor are one’s auditory nerves troubled driving or standing by a fuller sound than emanates from an eight day clock. There is no realisation of driving propulsion; the feeling as the passenger sits either at the front or the back of the vehicle is one of being wafted through the landscape.

The chassis was originally called the 40/50 and the power output was a rather relaxed 48 hp from just over 7 litres of capacity (the current Rolls-Royce Phantom V12 car develops 563 hp from 6.75 litres).

We have seen that the term ‘horsepower’ requires caution: it depends on the size of the horse. Early cars in Britain were taxed on a formula called RAC horsepower. It did not reflect the actual measured horsepower but was calculated by a formula including cylinder-bore size, number of cylinders and notional efficiency. Cars were commonly named for their taxable horsepower, such as the Austin Seven and the Riley Nine. The name ‘Rolls-Royce 40/50’ referred firstly to the taxable horsepower, 40, and the measured horsepower, 50. The unintended consequence of this foolish law was that manufacturers were obliged to design engines with pinchingly narrow bores and ludicrously long strokes. They were then stuck with inefficient sidevalves instead of overhead valves, which needed larger bores, setting back the design of British cars by 40 years. Exported British cars with asthmatic long-stroke engines blew up on the freeways of the USA, while short-stroke VW Beetles from Germany (which had a more intelligent fiscal law) rattled along for ever. And at one point the British led the world in diesel-engine technology, but this advantage was lost as a result of the heavy tax imposed on diesel fuel in the budget of 1938. Such was, and is, the scientific grasp of British politicians.

The gentle state of tune of the Rolls-Royce 40/50 made the engine delightfully flexible, and the ability to drive almost everywhere in top gear was of great importance to Edwardian motorists, many of whom could not manage the ‘crash’ gearboxes of the day and were unable to change gear on the move.

The chassis was built at first at Royce’s Manchester works, then production moved to a new factory at Derby, attracted by low rates offered by the town council.

The chassis of the 40/50 retailed at £985, and a suitable body could cost a further £110 14s, a staggering total which could have bought a house. The first customer was William Arkwright of Sutton Scarsdale Hall, Derbyshire, a descendant of Richard Arkwright, one of the founders of the Industrial Revolution. Initial sales were slow due to the high asking price. Claude Johnson realised that excellent though the new model was, it needed to be brought to public attention if the newly floated Rolls-Royce Ltd was to succeed. Johnson had an unerring eye for publicity. He used to balance a glass of water on the bonnet of the new 40/50 while the engine was taken up to 1,600 revolutions per minute, and not a drop would be spilt. He would also balance a penny on the end of the chassis and the penny would remain where it was. He then had an even better idea. He persuaded the factory to build a special ‘demonstrator’. This was chassis no. 60551, the twelfth 40/50 to be made. An open-topped Roi-des-Belges (King of the Belgians) body by Barker was fitted, which was specially finished in aluminium paint with silver-plated fittings. On the dashboard was a plaque with the name that Claude Johnson had chosen: ‘Silver Ghost’. This actual car, registration number AX 201, features largely in Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines. It is now considered the world’s most valuable car, and is insured for around $35 million.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.