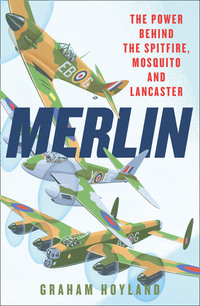

Merlin

Silver Ghost was a name that would resound down the years in the Rolls-Royce hall of fame, a name that at first referred to that particular car but eventually became applied to all 40/50s. What’s in a name? In the 1960s a new model of Rolls-Royce was about to be launched, called ‘Silver Mist’ to commemorate its illustrious ancestor, when the marketing department realised to their horror that ‘Mist’ meant ‘dung’ in German. The name was speedily changed to Silver Shadow. In this the car nearly joined the glorious pantheon of unfortunate car names such as the Studebaker Dictator (built in 1933), the Chevrolet Nova (‘it doesn’t go’ in Spanish), and the Buick LaCrosse, which in Québécois slang means ‘masturbator’. Not to mention the Mazda Titan Dump and the enigmatic Tarpan Honker. But ‘What’s in a name?’ asked Juliet. ‘That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet.’

Going so far upmarket meant that the only individuals who could afford a 40/50 Silver Ghost were royalty, dictators and the very wealthy. And ‘behind every great fortune lies a great crime’, as Balzac tells us.1 The Roi-des-Belges, or tulip phaeton, body might have appealed to the royal market, as the style began with a 1901 Panhard commissioned by Queen Victoria’s cousin Leopold II of Belgium: the Roi des Belges himself. The style of tulip-shaped seats was suggested by Leopold’s mistress, Cléo de Mérode, a dancer who was aged 22 when she met the king, then aged 61. (Leopold obviously lacked the scruples of Princess Teano, who wouldn’t remain in the same room as a dancer.)

Leopold founded and exploited the Congo Free State as his own personal business venture. Forced labour, punishment amputations, torture and murder were perpetrated upon the 20 million Africans under his rule, 10 million of whom died, according to Mark Twain. Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1899) describes the apocalypse that descended on the Congo under Leopold, and Roi-des-Belges also happened to be the name of the Belgian riverboat that Conrad commanded on the upper Congo in 1889. As the Roi-des-Belges body had no roof, the blood-soaked Leopold and his mistress du jour could be admired by the populace as he was chauffeured around the boulevards of Brussels.

Bolshevik royalty also enjoyed luxury cars. Vladimir Lenin’s Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost was purchased on 11 July 1922. Because of Moscow’s deep winter snows the car was fitted with caterpillar tracks at the rear and skis on the front wheels, so that the dictator could be driven from his Gorki mansion to the Kremlin. His chauffeur was Adolphe Kégresse, formerly Tsar Nicholas II’s personal driver (the Tsar had two Silver Ghosts). Lenin’s crimes were many; when famine swept his native Volga region in 1891, killing 400,000 peasants, he propagandised against charitable relief efforts from America because the spectacle of death might prove a ‘progressive factor’ in weakening the Romanovs. Stalin and Brezhnev also owned Rolls-Royces. Wherever history was being made there seemed to be a Rolls-Royce parked around the corner.

In India, the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, then the richest man in the world, ordered a Silver Ghost state limousine with a raised throne on gold mounts with four collapsible seats for attendants.* He died at the age of 45 before it was delivered.

Claude Johnson, the marketing genius of Rolls-Royce, had asked for a new radiator to be designed to be more in keeping with the company’s new upmarket image, and it proved to be another success, surviving up to the present day as the face of the company. At first sight it looks like a chrome-plated Greek temple, but there is more to it than that. Like the facets of the portico of the Parthenon it imitates, the flat faces of the Rolls-Royce radiator are slightly curved to give the illusion of straightness. There are no straight lines on the Parthenon, and even the columns are not straight along their vertical axes but swell in the middle. This ‘entasis’ is intended to counteract the optical effect in which columns with straight sides appear to the eye to be more slender in their middle – to have a waist. The ancient Greeks were masters of perspective. Without entasis the Rolls-Royce radiator would have the appearance of a chromium grin.

The Rolls-Royce radiator is also a triumph of iconography. ‘The composition of the radiator’, observed Professor Erwin Panofsky, ‘sums up, as it were, twelve centuries of Anglo-Saxon preoccupations and aptitudes: it conceals an admirable piece of engineering behind a majestic Palladian front; but this Palladian front is surmounted by the wind-blown “Silver Lady” in whom art nouveau is infused with the spirit of unmitigated Romanticism.’2 Panofsky traces Inigo Jones’s introduction of Palladian Classicism to the facades of stately homes such as Lord Burlington’s Chiswick House. The aristocrat being driven by his servant in a Rolls-Royce would feel as though he was being preceded by his own front door.

In 1910 there was a brief craze for bonnet mascots, and Johnson decided to have one designed for his classic radiator. He asked the sculptor Charles Robinson Sykes to design an ornament conveying ‘the spirit of the Rolls-Royce, namely, speed with silence, absence of vibration, the mysterious harnessing of great energy and a beautiful living organism of superb grace’. The grimly pragmatic Henry Royce objected that the mascot interfered with the driver’s view. Sykes had already sculpted a mascot for Lord Montagu’s 1909 Silver Ghost. His model was allegedly Eleanor (Nellie) Thornton, Montagu’s secretary and secret mistress, and the figurine held one finger to her lips to symbolise their secret love affair. It was dubbed The Whisperer, and when Sykes received his commission for The Spirit of Ecstasy the model was once again Thornton. Nellie had a daughter by Montagu (whom she gave up for adoption), but she was drowned with hundreds of fellow passengers in 1915 when the SS Persia was torpedoed by U-boat U38. Lord Montagu survived the sinking.

Claude Johnson’s ‘Silver Ghost’ demonstrator was prepared for a crack at a world record: the non-stop reliability run. A team of drivers, including Johnson and Rolls, drove the car with the press aboard on the course of the Scottish Reliability Trials, and they broke record after record.

What was it like to drive? As you climb aboard you notice a large, cranked windscreen with a view over the bonnet which makes it look surprisingly short. The Grecian radiator constantly reminds you that you are driving a Rolls-Royce. On top of the unsupported upright steering column is a big four-spoke wheel with a polished wooden rim. On that is a control cluster with two levers, labelled Fast/Slow and Early/Late, and the Governor. The plain-speaking Henry Royce thought that ‘early/late’, referring to the spark timing, was more understandable than the more usual ‘advance/retard’. A plate on the scuttle reads: ‘Rolls-Royce Ltd., London & Manchester’ and gives the car number as 551. The driver has a snake-like bulb-horn and the front passenger is also provided with a Desmo bulb-hooter, mounted outside below the left elbow. Outboard of the driver’s door, and between it and the spare tyre, are the silver-plated gear and brake levers. The gear gate is unusual, as 1st is forward and left but 2nd and 3rd positions are both down and back, then with a short movement forward into the overdrive top; reverse is between bottom and top. The handbrake operates the cable-applied rear-wheel brakes, which are fairly quiet. The footbrake is little used; it works on the transmission and is likely to bind in hot weather and lock the back wheels in a skid. The accelerator pedal is to the right of the brake, unusually for those days – it was often between the clutch and brake pedals. Beside the spare wheel there is a Cowley speedometer reading from 10 to 80 mph, with a little clock above it. The engine is idling silently.

When you drive off the Ghost will perhaps feel rather lorry-like, with a heavy clutch and the odd crunch of gears, but the flexible engine soon gets you up to 30 mph, which is a comfortable cruising speed even on main roads. The ride is surprisingly good. The passenger sits high in a comfortable leather armchair and has to maintain 1 lb fuel pressure with a vertical floor-mounted bicycle-like plated air pump, watching the gauge that reads to 4 lb/square inch. This needs constant attention, or else the engine will stop. Otherwise you glide along in silence. This is the best of Edwardian motoring.

Johnson collected a Gold Medal on his non-stop reliability run. Then the Silver Ghost continued on a journey between London and Glasgow 27 more times without stopping the engine except for Sundays, when the car was locked in a garage. After 15,000 miles had passed Johnson invited the RAC scrutineers to strip the engine and chassis down and advise on what parts had to be replaced to return the car to ‘as new’ condition. The engine was passed as perfect, but one or two parts of the steering had slight wear, and so did the joints in the magneto drive; altogether costing £2 2s 7d (about £250 in today’s terms). A private owner would not have needed to replace anything. This was a standard of reliability that far exceeded anything Rolls-Royce’s competition could manage, and Johnson made sure he broadcast their success everywhere. For a while the ‘Silver Ghost’ was the most famous car in the world. Not everyone was an admirer, though. Laurence Pomeroy of Vauxhall described the Rolls-Royce as a triumph of workmanship over design, by which he suggested they placed too much reliance on correcting errors that other manufacturers would have avoided in the first place. This was a criticism that could also be levelled at the Rolls-Royce Merlin.

The 40/50s were also used as rally cars. The Austrian Alpine Trial was an eight-day reliability run, known as the toughest rally in Europe and involving steep mountain passes. In 1912 a Silver Ghost was privately entered by James Radley, the pilot who had first reached Charles Rolls after his fatal crash at Bournemouth. Embarrassingly, its three-speed gearbox proved inadequate for the ascent of the Katschberg Pass, as Radley’s car ground to a halt and would only continue when two passengers got out and walked. The factory took this failure seriously and only one solution was possible if the car was to maintain its reputation. The Rolls-Royce perfectionism was brought into play and cars were sent out to the Alps to reconnoitre the passes. A factory team of four cars was prepared for the 1913 event with lower-ratio four-speed gearboxes with the engine power increased to 75 bhp. This time the passes were conquered:

The Rolls-Royces came past in great style, and I am bound to say that I have never seen anything as beautiful in the way of locomotion than the way in which they flew up the pass; we all know what a fast car is like on the level; but the sight of a group of cars running up a mountain road at high speed, with a superbly easy motion to which each little variation in the surface gave the semblance of a greyhound in its stride, was inspiring to a degree.3

This time Radley finished first in all the stages, and the team gained six awards including the Archduke Leopold Cup. Replicas of the victorious cars were put into production and sold officially as Continental models, but they were called Alpine Eagles by chief test driver (and later Rolls-Royce Managing Director) Ernest Hives. The whole experience also made Henry Royce wary of entering into competition.

There was competition in the marketplace, though. A new sleeve-valve engine was announced by the Daimler company which was said to be even quieter than the Silver Ghost’s engine. Johnson wrote: ‘It is quite difficult to know how far the new Daimler valveless engine is going to affect us. The engine is wonderfully silent.’ As we have seen, poppet valves look like pennies on a stick and are pushed down by the camshaft lobes to open the inlet and exhaust ports. In contrast to poppet valves the sleeve valve is an extra liner between the piston and the cylinder, like a tin can with no ends and with cut-out holes in the sides. These uncover bigger ports by quietly sliding up and down and side to side: the action you might employ to dry the inside of a beer glass with a dish towel. The sleeve valve required less maintenance and allowed a better-shaped combustion chamber, but higher initial cost and greater oil consumption limited the sleeve valve’s appeal to car manufacturers. It had a future, though, in Bristol and Napier Sabre aero engines.

* This was chassis number 2117, and the car’s total lifetime mileage was only 356.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.