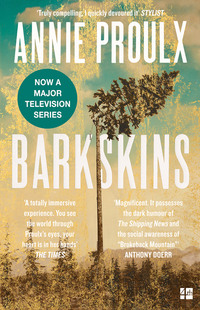

Barkskins

“You’ve held an ax before; you have a woodsman’s skill.” René told him about the Morvan forest where he and Achille had cut trees. But already that life was unmoored and slipping sidewise out of memory.

“Ah,” said Monsieur Trépagny. The next morning he took their wretched axes from them and went off, leaving them alone.

“So,” said René to Duquet, “what is Monsieur Trépagny, is he a rich man? Or not?”

Duquet produced a hard laugh. “I thought that between you and Monsieur Trépagny all the knowledge of the world was conquered. Do you not know that he is the seigneur and we the censitaires?—what some call habitants. He is a seigneur but he wants to be a nobleman in this new country. He apportions us land and for three years we pay him with our labor and certain products such as radishes or turnips from the land he allows us to use.”

“What land?”

“A fine question. Until now we have been working but there has been no mention of land. Monsieur Trépagny is full of malignant cunning. The King could take the seigneurie from him if he knew. Did you really not understand the paper you signed? It was clearly explained in France.”

“I thought it concerned only a period of servitude. I did not understand about the land. Does that mean we are to be farmers? Landowners?”

“Ouais, plowmen and settlers, not landowners but land users, opening the forest, growing turnips. If people in France believed they could own land here outright they would rush in by the thousands. I for one do not wish to be a peasant. I don’t know why you came here but I came to do something. The money is in the fur trade.”

“I’m no farmer. I’m a woodsman. But I would like to have my own land very much.”

“And I would like to know why he took my tooth. I saw him.”

“And I, too, saw this.”

“There is something evil there. This man has a dark vein in his heart.”

Monsieur Trépagny returned a few hours later with iron axes for them, the familiar straight-hafted “La Tène” René had known all his life. They were new and the steel cutting edges were sharp. He had brought good whetstones as well. René felt the power in this ax, its greedy hunger to bite through all that stood in its way, sap spurting, firing out white chips like china shards. With a pointed stone he marked the haft with his initial, R. As he cut, the wildness of the world receded, the vast invisible web of filaments that connected human life to animals, trees to flesh and bones to grass shivered as each tree fell and one by one the web strands snapped.

After weeks of chopping, limbing and bark peeling, of dragging logs to Monsieur Trépagny’s clearing with his two oxen, cutting, notching and mortising the logs as the master directed, lifting them into place, chinking the gaps with river mud, the new building was nearly finished.

“We should be building our own houses on our assigned lands, not constructing a shared lodging next to his ménage,” Duquet said, his inflamed eyes winking.

Still they cut trees, piling them in heaps to dry and setting older piles alight. The air was in constant smoke, the smell of New France. The stumpy ground was gouged by oxen’s cloven hooves as though a ballroom of devils had clogged in the mud: the trees fell, their shadows replaced by scalding light, the mosses and ferns below them withered.

“Why,” asked René, “do you not sell these fine trees to France for ship masts?”

Monsieur Trépagny laughed unpleasantly. He loathed René’s foolish questions. “Because the idiots prefer Baltic timber. They have no idea what is here. They are inflexible. They neglect the riches of New France, except for furs.” He slapped his leg. “Even a hundred years ago de Champlain, who discovered New France, begged them to take advantage of the fine timber, the fish and rich furs, leather and a hundred other valuable things. Did they listen to him? No. Very much no. They let these precious resources waste—except for furs. And there were others with good ideas but the gentlemen in France were not interested. And some of those men with ideas went to the English and the seeds they planted there will bear bloody fruit. The English send thousands to their colonies but France cannot be bothered.”

As spring advanced, moist and buggy, each tree sending up a fresh fountain of oxygen, Duquet’s face swelled with another abscess. Monsieur Trépagny extracted this new dental offense and said commandingly that now he would pull them all and Duquet would waste no more time with toothaches. He lunged with the blacksmith’s pliers but Duquet dodged away, shook his head violently, spattering blood, and said something in a low voice. Monsieur Trépagny, putting this second tooth in his pocket, spun around and said in a silky, gentleman’s voice, “I’ll have your skull.” Duquet leaned a little forward but did not speak.

Some days later Duquet, still carrying his ax, made an excuse to relieve his bowels and walked into the forest. While he was out of earshot René asked Monsieur Trépagny if he was their seigneur.

“And what if I am?”

“Then, sir, are we—Duquet and I—to have some land to work? Duquet wishes to know.”

“In time that will occur, but not until three years have passed, not until the domus is finished, not until my brothers are here, and certainly not until the ground is cleared for a new maize plot. Which is our immediate task, so continue. The land comes at the end of your service.” And he drove his ax into a spruce.

Duquet was gone for a long time. Hours passed. Monsieur Trépagny laughed. He said Duquet must be looking for his land. With vindictive relish he described the terrors of being lost in the forest, of drowning in the icy river, being pulled down by wolves, trampled by moose, or snapped in half by creatures with steaming teeth. He named the furious Mi’kmaw spirits of the forest—chepichcaam, hairy kookwes, frost giant chenoo and unseen creatures who felled trees with their jaws. René’s hair bristled and he thought Monsieur Trépagny had fallen too deeply into the world of the savages.

The next day they heard a quavering voice in the distant trees. Monsieur Trépagny, who had been limbing, snapped upright, listened and said it was not one of the Mi’kmaw spirits, but one that had followed the settlers from France, the loup-garou, known to haunt forests. René, who had heard stories of this devil in wolf shape all his life but never seen one, thought it was Duquet beseeching them. When he made to call back Monsieur Trépagny told him to shut his mouth unless he wanted to bring the loup-garou closer. They heard it wailing and calling something that sounded like “maman.” Monsieur Trépagny said that to call for its mother like a lost child was a well-known trick of the loup-garou and that they would work no more that day lest the sound of chopping lead the beast to them.

“Vite!” Monsieur Trépagny shouted. They ran back to the house.

2

clearings

With Duquet gone—“eaten by the loup-garou,” said Monsieur Trépagny with lip-smacking noises—the seigneur became talkative, but told differing versions of his history while he chopped, most of his words lost under the blows of the ax. He had a skilled eye that could see where small trees stood more or less in a row, and these he would notch, then fell the great tree at the end, which obligingly took down all the small trees. He said his people came from the Pyrenees, but another time he placed them in the north, in Lille, nor did he neglect Paris as his source. He described his hatred of villages and their lying, spying, churchy inhabitants. He despised the Jesuits. Monsieur Trépagny said he, his brothers and their uncle Jean came to New France to enter the fur trade, although he himself had better reasons.

“Our people in earlier times were badly treated in France. The popish demon church called us heretics and tortured us. They believed they had conquered us. They were wrong. We have held to our beliefs hand, head, heart and body in secret for centuries and here in New France we will grow strong again.” He extolled the new land, said it would surpass Old France in richness and power.

“A new world that will become greater than coldhearted old France with its frozen ideas. Someday New France will extend all the way to Florida, all the way to the great river in the west. Frontenac saw this.”

René thought of it and agreed, New France was a prize if England kept away. But he did not often think of such things. He saw himself as a dust mote in the wind of life, going where the drafts of that great force carried him.

“What,” asked Monsieur Trépagny, “is the most important thing? After God, of course.”

René wanted to say land, he wanted to say seeds, he wanted to say stolen teeth. He didn’t say anything.

“Blood!” said Monsieur Trépagny. “Your family. Your blood people.”

“They are all dead,” said René, but Monsieur Trépagny ignored him and continued his history. He and his brothers, he said, went first up the mysterious Saguenay River “to barter with the Hurons for furs, and later with the Odaawa, building up trust, but we avoided the Iroquois, who love the English and who, from childhood, practice testing themselves against horrible tortures. They enjoy inflicting pain on others. The voyageurs’ life is a good life for my brothers, who still ply the rivers. For me, a very disagreeable way.

“Now,” he said, “the Iroquois are less terrible than in former times. But all Indians were mad for copper kettles, the bigger the better, so large they could not be easily moved, and the possession of a kettle changed their wandering ways. Once they had that copper or iron kettle no longer did they roam the forests and rivers so vigorously. Villages grew up around the kettles. All very well, but someone had to carry those monstrous vessels to them, someone had to toil and haul them up dangerous portage routes.” He pointed silently at his breast. “This was below my station in life.” And he smote his tree.

“The fur trade moved north and west,” he said to the tree as he told of his disenchantment. “The portages. Six, eight miles of rocks with two fur packs the weight of a cow, then back to the canoe and more packs or one of the cursed kettles. Finally, the canoe. You would not believe the enormous loads some of those men carried. One is said to have carried five hundredweight each trip from early morning until darkness.” Carrying one of the detested kettles, said Trépagny, his right knee gave way. The injury plagued him still.

“However! The fur company, with the rights the King assigned them, made me a seigneur and charged me to gather habitants and populate New France. This is the beginning of a great new city in the wilderness.”

René asked a question that had bothered him since the first trek through the woods.

“Why do we cut the forest when there are so many fine clearings? Why wouldn’t a man build his house in a clearing, one of those meadows that we passed when we walked here? Would it not be easier?”

But Monsieur Trépagny was scandalized. “Easier? Yes, easier, but we are here to clear the forest, to subdue this evil wilderness.” He was silent for a minute, thinking, then started in again. “Moreover, here in New France there is a special way of apportioning property. Strips of land that run from a river to the forest give each settler fertile farm soil, high ground safe from floods, and forest trees for timber, fuel and—mushrooms! It is an equitable arrangement not possible with clearings taken up willy-nilly—bon gré mal gré.”

René hoped this was the end of the lecture but the man went on. “Men must change this land in order to live in it. In olden times men lived like beasts. In those ancient days men had claws and long teeth, nor could they speak but only growled.” He made a sound to show how they growled.

René, chopping trees, felt not the act but the pure motion, the raised ax, the gathering tension in arms and shoulders, buttocks and thighs, the hips pivoting, knees loose and flexed, and then the swing downward as abstract as the shadow of a stone, a kind of forest dance. He had bound a rock to the poll with babiche to counterbalance the heavy bit. It increased the accuracy of each stroke.

Monsieur Trépagny launched into a droning sermon on the necessity, the duty of removing the trees, of opening land not just for oneself but for posterity, for what this place would become. “Someday,” Monsieur Trépagny said, pointing into the gloom, “someday men will grow cabbages here. To be a man is to clear the forest. I don’t see the trees,” he said. “I see the cabbages. I see the vineyards.”

Monsieur Trépagny said his uncle Jean Trépagny, dit Chamailleur for his disputatious nature—Chama for short—would take Duquet’s place. He was old but strong, stronger than Duquet. He would arrive soon. Monsieur Trépagny’s brothers would also come. Eventually. And he said the time for felling trees was now over. The bébites were at their worst, the wet heat dangerous, the trees too full of sap. Indeed, the hellish swarms of biting insects were with them day and night.

“Winter. Winter is the correct time to cut the forest. Today is the time for removing stumps and burning.” It was also the time, he added, for René to begin to fulfill his other duties.

“For three days a week your labor is mine. As part of your work,” said Monsieur Trépagny, “you are to supply my table with fish.” The more immediate work involved preparing the gardens for Mari. The oxen, Roi and Reine, pulled Monsieur Trépagny’s old plow sullenly. A savage fly with a green head battened on their blood. Monsieur Trépagny smeared the animals with river clay, which hardened into dusty clots but could do nothing about the clustering gnats. But Mari, the Indian woman, steeped tamarack bark in spring water and twice daily sluiced their burning eyes. In the long afternoons, with many sighs, she planted the despised garden. One day that summer she sent her two young sons to a place called Odanak, where remnants of her people had fled.

“Goose catch learn them. Many traps learn. Good mens there hunting. Here only garden, cut tree learn.”

Monsieur Trépagny said acidly that what they would learn would be rebellion against the settlers and warfare.

Mindful of his fishing duties René went to the river. Monsieur Trépagny had given him a knife, fishhooks, a waxed linen line and a large basket for the fish. In the river fish were large and angry and several times the linen line parted and he lost a precious hook. But Mari was scornful. “Small fish,” she said. “Good fisherman not Lené. My people make weirs, catch many many. Big many.”

To divert her irritation he pointed at a stinging nettle in the garden. “We have those in France,” he said.

“Yes. Bad plant grow where step whiteman people—those ‘Who is it Coming’—Wenuj.”

Mari asked him to leave the fish intact—she would clean them herself. She buried the entrails in the garden and when René asked her if that was the Indian way she gave him a look and said it was a common practice for all fools who grew gardens instead of gathering the riches of the country.

“Eels!” she said. “Eels catch. Eels liking us. We river people.”

She wove three eel traps for him and gave him fish scraps for bait, went with him to the river and showed him likely places to try. Almost every day thereafter he brought her fat eels. She said the Mi’kmaq had many ways to catch eels and that the traps were best for him. When her sons came back from the Abenaki village of Odanak they could show him other ways.

In early July the pine trees loosed billows of pollen, yellow plumes like citrine smoke drifting through the forest, mixing with the smoke from burning trees. One morning an old man, his back bent beneath a bundle, his glaring eyes roving left and right, came ricketing out of the pollen clouds from the west trail, which led, as far as René knew, to the end of the world. Above the little mouth stretched a grey mustache like a bit of sheep’s wool caught on a twig. The eyes were like Monsieur Trépagny’s eyes, black and white and rolling. Chamailleur looked at René, who was preparing to go fishing, and started in at once.

“Salaud! You bastard! Why are you not working?”

“I am. It is part of my duty to supply the house with fish for the table.”

“What! With a string and a hook? You must use a net. Have the woman make a net. Or a basket trap. Or you must use a spear. Those are the best ways.”

“For me the line and hook are best.”

“Stupid and obstinate!—oui, stupide et obstiné! I know what is best and you do not. It is good I came. I can see you need correction. My nephew is too easy.”

René continued stubbornly with his hooks and twisted linen line. But he thought about nets. A net might be better, for the fish were so thick in the river he might get several large ones at the same time. As for Mari’s insufferable speechifying on the ways the Mi’kmaq built different kinds of weirs, how they hunted esturgeon at night with blazing torches and spears—he ignored all she said. He did use the eel traps she had made, excusing himself on the ground that eels were not fish.

Searching for land to claim when his servitude ended, he discovered Monsieur Trépagny’s secret. He had walked far upstream. Recent rains had enlarged the river to a bounding roar over its thousands of rocks. He thought it might be best to choose land not too close to the river, but something with a spring or modest stream. He made his way through an old deadfall where in between the fallen trees millions of saplings grew, as close together as broom straws. Twice he heard a great crashing and saw a swipe of black fur disappear into the underbrush. In early afternoon he came onto a wide but faint trail trending east-west and wondered if it might connect to Monsieur Trépagny’s clearing to the east. Instead, with the afternoon before him, he turned west. He saw traces of old ruts that could only have been made by a cart. It was not an Indian trail. Now he was curious.

In midafternoon the trail divided. He followed the wagon ruts. The way became markedly different in character than the usual forest path. Trees had been carefully cleared to create the effect of an allée, the ground thinly spread with thousands of broken white shells. He saw this allée ran straight, a dark tunnel of trees with a pointed cone of light at the end. He had seen these passageways in France leading to the grand houses of nobles, although he had never ventured into one. And here, in the forests of New France, was the blackest, harshest allée of the world, the trees like cruel iron brushes, white shells cracked by deer hooves. The end of the allée seemed filled with light, a void at the limit of the tilting earth.

A massive pale thing loomed up, a whitewashed stone house, almost a château, that might have been carried on the sea winds from France and dropped in place. René knew that this was Monsieur Trépagny’s domus, the center of his secret world. There were three huge chimneys. The windows were of glass, the roof of fine blue slate, and a slate walkway curved around the building, leading to a fenced enclosure. The fence was tall, formed of ornate metal rods. Everything except the stone had come from France, he knew it. It must have cost a fortune, two fortunes, a king’s ransom. It was the proof of the seigneur’s madness, his mind clotted with old heretic ideas of clan and domus, himself the king of an imaginary world.

Disturbed, René cut back to the main trail and followed it east. Dusk was already seeping in. Night came quickly in the forest, even in the long days. As he had guessed, the trail ended in Monsieur Trépagny’s clearing. He went straight to the cabin he now shared with Chama, who was rolled up in Duquet’s old beaver robe, snoring and mumbling.

The summer months went on. Chama, bossy and cursing, decided where they would cut. They cleared trees, dragging stumps into line to form a bristled root fence. René fished for the table, listened to Mari tell Mi’kmaw stories to Elphège, Theotiste and Jean-Baptiste about beaver bone soup and rainbow clothes and the tiny wigguladumooch, and as he absorbed that lore he watched Monsieur Trépagny and wondered about his secret house, which later he learned the seigneur had named Le Triomphe. He had the coveted particule and could call himself Claude Trépagny du Triomphe.

The heat of summer disappeared abruptly. Overnight a wedge of cold air brought a new scent—the smell of ice, of animal hair, of burning forest and the blood of the hunted.

3

Renardette

Violent maples flared against the black spruce. Rivers of birds on their great autumnal journeys filled the skies—Hudsonian godwits, whole nations of hawks, countless black warblers—paruline rayée—looking like tiny men with their black berets, chalky faces and dark mustache streaks, cranes, longspurs, goldeneyes, loons, sparrows, flycatchers, warblers, geese. The first ice storm came one night in October. Then the world pressed flat, snow hissing in the spruce needles, the sun dimmed by a grisaille wash. The forest clenched into itself as though inhaling a breath.

Mari’s sons Elphège and Theotiste returned from Odanak carrying traps and snares, whistles and calls to lure game. Mari was intensely interested in these objects, but Monsieur Trépagny called them rubbish and threw Theotiste’s beaver funnel trap into the fireplace. René watched the boy’s face harden, watched how he kept his eyes lowered, not looking at Monsieur Trépagny. For a moment he saw in Theotiste the cruel Indian.

December brought stone-silent days though a fresh odor came from the heavy sky, the smell of cold purity that was the essence of the boreal forest. So ended René’s first year in the New World.

Snow heaped in great drifts smothered the trees so thickly they released avalanches when the wind rose. René learned he had never before in his life experienced extreme cold nor seen the true color of blackness. A burst of ferocious cold screwed down from the circumpolar ice. He woke in darkness to the sound of exploding trees, opened the door against a wall of palpable chill, and his first breath bent him in a spasm of coughing. Jerking with cold he managed to light his candle and, as he knelt to remake the fire, he saw minute snow crystals falling from his exhaled breath.

At breakfast Monsieur Trépagny said it was too cold to cut trees. “On such a day frozen ax blades shatter and one burns the lungs. Soon you cough blood. Then you die. It will be warmer in a few days.”

When René mentioned hearing trees explode, the seigneur said that in such intense cold even rocks could not bear it and burst asunder. Folding gelid moose bone marrow into a piece of bread he said, “One winter, after such a cold attack, I came upon four deer frozen upright in the forest.”

“Ah, ah,” said Chama, “one time in the north when the weather was warm and pleasant for ten days, then, in a single breath, a wind of immeasurable cold descended like an ax and the tossing waves in the river instantly froze into cones of ice. We prayed we would not do likewise.”

It was during this cold period that Mari’s youngest child, Jean-Baptiste, who from infancy had suffered a constant little cough, became seriously ill; the cough deepened into a basso roar. The child lay exhausted and panting.

The moon was a slice of white radish, the shadows of incomparable blackness. The shapes of trees fell sharply on the snow, of blackness so profound they seemed gashes into the underworld. The days were short and the setting sun was snarled in rags of flying storm cloud. The snow turned lurid, hurling away like cast blood. The dark ocean of conifers swallowed the afterglow. René was frightened by the intensity of the cold even in the weak sunlight, and by Jean-Baptiste’s sterterous wheezes coming from his pallet near the fire, his weakening calls to Mari and finally the everlasting silence. Monsieur Trépagny said coldly, “All must pay the debt of nature.”