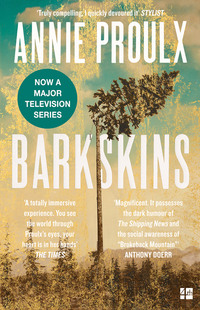

Barkskins

René had been thinking of what they said of their companion who would stay in Wobik with the fur packs, thinking of the man he had seen disappear into the spruce shadow, and he knew with sudden surety who it was.

“This one who stays in Wobik, does he have bad teeth?”

“Bad teeth? No. Chalice! He has no teeth at all. He dines on mush and broth. He cannot eat pemmican and would be a liability did he not prepare his own repasts.”

“Is his name perhaps Duquet? Or something else?”

“Duquet. How do you know?”

“He was an engagé with me, on the same ship and hired to the same man—your brother Monsieur Claude Trépagny. He disappeared into the woods one day. Your brother believes he was caught and eaten by the loup-garou.”

“Hah! He was not eaten, or if so, only a little around the edges. He is a man of affairs. He knows the important men in the fur trade—even the English. He says he will be a rich man one day.”

René had his own idea of why Duquet did not wish to see Monsieur Trépagny.

The reunion of the brothers and their uncle Chama was noisy and sentimental. They all wept, embraced, cursed, swigged whiskey, slapped each other on the back, looked earnestly at one another, wept again and talked. The brothers disapproved of the clearing. Their own way of life left no scars on the land, they said, denuded no forests. They glided through the waterways and in seconds the wake of their passage vanished in the stream flow and the forests remained as they had been, silent and endless.

“Uncle, you must come back with us to the high country, what good times we’ll have again.”

But Chama smiled sadly. He had a spine deformity that every year twisted him a little more sideways. He was no longer able to bear the hard voyageur life, a statement which motivated the pitiless brothers to describe tremendous paddling feats—twenty hours, thirty hours—without a pause. They named heroes of the water, wept for the memory of a friend who broke his leg so that the bone protruded from the bunched flesh. They had put him up to his neck in the icy water to die.

“Not long enough to sing all of ‘J’ai trop grand peur des loups,’ which he asked us to sing. It was his favorite, that song—‘I have a great fear of wolves.’ And he sang the verses with us with chattering jaws until his heart slowed and he made the mortal change.”

This started them off on stories of coureurs de bois who suffered untimely ends.

“… And Médard Baie, who suffered painful stomach cramps and died of the beaver disease?”

“That poison plant that beaver eat with great pleasure, and I have heard the Indians, too, eat of it, but it is death for a Frenchman.”

The wedding was four days away as the bride was traveling from Kébec and not expected for at least another three sunrises. A priest, not Père Perreault, but a more important cleric from Kébec, would accompany her. The marriage sacrament would take place in Monsieur Trépagny’s big house. Even now, still in his lightly soiled Parisian finery, the seigneur was directing two Mi’kmaw men loading a wagon of goods for transport to that elegant structure. Fires burned in the great fireplaces to take away the damp, the floors were strewn with sweet-grass. Those same Indians, with Chama’s help, had constructed a long table under the pines. Everything was ready—except the food.

“Mon Dieu!” shouted Monsieur Trépagny. He had forgotten the need for a cook when he sent Mari away, and only now realized the great problem.

“What problem?” bawled Toussaint. “Feed them pemmican! We feed twenty-five men a day on the stuff and it does them good.”

Monsieur Trépagny turned to René and said, “Vite! Vite. Hurry back to Wobik and get Mari. Bring her here. Bring whatever she needs to make a wedding feast. We will procure game and fish while you are gone. Vite!”

Mari and Renardette were sitting outside the mission house plucking birds. Mari heard Monsieur Trépagny’s demand stoically and kept on pulling feathers, which she dropped to the ground. The light breeze sent them bouncing and rolling. The minutes passed and Mari said nothing.

“So will you come right now? With me? I am to carry any provisions you need. Monsieur Trépagny gave me this for you”—he showed a bright coin. “And this for what you need to make this feast”—and he showed the second coin.

“Elphège shoot good duck with arrow,” she said, turning it so he could admire the fat breast. He glanced at Elphège, who grinned and put his head down shyly.

“A very handsome duck,” he said. “Finest duck in New France. Maybe Monsieur Trépagny would pay you for that duck.”

“It is for Maman,” said Elphège, then, overcome with so much social intercourse, he fled to the back of the building.

Renardette stood off to the side, rubbing the dirt with her heel in a semicircular design. “I have good beer back at Monsieur’s house.”

René understood that Mari preferred to stay where she was and roast Elphège’s duck. But she stood up, and he followed her into the mission house.

She put the cleaned duck in a pack basket. She gathered jackets, then said, “Père Pillow not here. Not know. Letter write me.” She got a pen and inkwell from the shelf, found a scrap of paper and, sitting at the table, made a parade of marks on it.

“What did you write?” René asked, consumed with curiosity.

“That feather say, ‘Cook three suns.’ That write me.”

He could see with his own eyes that Mari knew writing, though he thought her letters looked like worm casts, nothing like his exquisite R.

On the way Mari made several side forays to gather wild onions, mushrooms and green potherbs. She spent a long time searching along the river for something in particular, and when she found it—tall plants with feathery leaves—she stripped off seed heads and put them in a small separate bag. When they arrived at Monsieur Trépagny’s clearing, the brothers had butchered six does and Chama was crouched over a large sturgeon, scooping roe into a bucket with his hands. Mari said nothing to any of them but went into the old house and began to haul out pots and kettles to be shifted to the wedding house. From the cupboard she took dried berries and nuts. She found the sourdough crock, neglected in her absence, scraped the contents into a bowl, added flour and water and covered it over, carried it to the cart. She put the seeds she had gathered at the riverside into the cupboard on the top shelf. She spoke to Monsieur Trépagny in a low voice, so quiet in tone only he heard.

“Tomorrow bread bake. Tomorrow all cook. Then mission.”

“Eh,” said Monsieur Trépagny. “We’ll see.”

5

the wedding

Philippe Bosse was to bring the bride, her maidservant and the priest to the wedding house in his freshly painted cart. The brothers and their trapper comrades drank and wrestled under the pines. Monsieur Trépagny paced up and down, dashed into the house to adjust something, out again to look into Mari’s pots, then to peer into the gloom of the dark allée. Elphège had built Mari’s cook fire, a long trench where the venison haunches could roast on their green sapling spits and the great sturgeon, pegged to a cedar plank, sizzle. Mari ran back and forth between the fire trench and a small side fire, where she cooked vegetables and herbs. In one pot she simmered a kind of cornmeal pudding with maple syrup and dried apples, a pudding that Monsieur Trépagny loved to the point of gluttony. As it bubbled and popped she sifted in the seeds she had gathered at the streamside.

In clumps and couples the guests from Wobik began to arrive and they sat about drinking Renardette’s good beer and talking, admiring Monsieur Trépagny’s fine house. They looked into the great bedroom hung with imported tapestries and with inquisitive, work-worn fingers touched the pillows plump with milkweed down.

“It’s like old France.”

“Dieu, maybe too much like …”

They heard the bride long before they saw her.

“Hear that!” said Elphège. The company fell silent, listening. Suddenly three deer burst out of the forest, scattered in different directions. They all heard a distant ringing sound that gradually grew louder until it revealed itself as a high-pitched, strident female voice in a passion shrieking, “I refuse! Cheat! Impostor! Skulking savages! Uncivilized! Peasants! Nothing but trees! I have been duped! My uncle has been duped! Someone will pay! I refuse! I will return to Paris! Je vais retourner à Paris!” And it was still ten minutes before Philippe Bosse’s fur-lined cart turned into the allée.

Toussaint said to Fernand, “She is so ugly she must be very, very rich.” The bride’s face was crimson, enhanced by a liberal application of French red, her orange hair protruding from under her wig. The lady’s maid looked as if she might carry a poignard in her garter. One bony hand gripping the side of the cart the imported priest, Père Beaulieu, sat stone-faced. The bride’s eye fell on Monsieur Trépagny.

“You!” she said. “You will explain this monstrosity”—and she waved disdainfully at Monsieur Trépagny’s fine house. “What a shack. C’est un vrai taudis! Explain to me how this hut in the forest is a fine manor house and the site of a great rich city as you told my guardian uncle.” She sprang from the cart with the elasticity of an Inuit hunter, and the voyageurs applauded. She scorched them with a fiery look of disdain and marched into the house with the maid, Monsieur Trépagny and Père Beaulieu following.

Philippe Bosse complained in a low voice to his listeners. “I said, ‘Madame, I have contracted to bring you to Monsieur Trépagny’s fine house in this fine forest and I will do it. What follows is for him to decide.’”

They expected the bride, her dangerous-looking maid and the bony priest to come out of the house at any instant and get back into the wagon and roll away to France. But none of them appeared. The wedding guests could hear their voices—the bride’s hot and savage, upbraiding and sarcastic; Monsieur Trépagny’s cajoling, imploring and explaining; the priest’s murmuring and calming. As the hour passed the bride’s voice softened, Monsieur Trépagny’s soared.

Toussaint, Fernand and Chama had listened to it all before, as had René. Those familiar words! “Rich forests … unimaginable hectares of land … fertile soil … fish to feed the world … powerful rivers … beautiful cities of the future … the domus.”

Twilight fell and Chama, Elphège and Philippe Bosse built a bonfire. The voyageurs sampled the barrel of whiskey. They waited.

“After all, there’s the feast,” said Toussaint yearning toward the food. He and his comrades moved toward the table where Mari had set out the kettle of stewed eels, the roasted sturgeon, the fat duck in an expensive sugar sauce, platters of corn cakes, moose cacamos, the legs of venison done so they were crispy on the outside, tender in the teeth, various porridges and sauces. Down the length of the table paraded bottles of cherry brandy. Before they could touch the savory dishes there was a cry to wait. Monsieur Trépagny stood on the fine stone doorstep, and behind him was Mélissande du Mouton-Noir, her face red and corrugated in the light of the bonfire. Monsieur Trépagny spread out his arms as if he were a wild goose readying for flight.

“Attention!” he cried. “Will the guests please enter.”

There was an excited murmur and anticipatory cheers.

Inside the drawing room the guests sat on still-splintery plank benches, taking in the parquet floor, the ornamented couvre-feu, gaping at the fairy-like chandelier, its crystal prisms shattering the candle flames into a thousand darts that contributed the feeling of a cathedral to the marriage ceremony. The Wobik women gazed enviously at the elaborate wrought-iron chimney crane that could hold pots in three positions.

After the ceremony, the celebration began. Elphège built up the bonfire and the flames threw flaring shadows on the scene. The guests approached the table, the voyageurs rushing, stabbing and hacking, the Wobik residents picking at the feast meats with refined airs felt they were in fine society. Monsieur Trépagny produced bottles of many shapes: red wine, rum, brandy, whiskey—even champagne, real French champagne. Two of the voyageurs brought out fiddles and began to play while the others clapped and sang. The loud music and the violent stamping of the dancers, their sashes whipping and curling in the firelight as they leapt, drove off any pretensions to gentility. Even the red-faced bride danced, and Monsieur Trépagny was a madman of athletic brilliance. The distorted sound bounced off the forest trees and any nearby evil spirits shrank into the earth until it should be over. Under a bush, covered with a dish towel, waited the cornmeal pudding with its potent water hemlock seeds, Mari’s farewell dish for Monsieur Trépagny. She waited for the right moment to present it.

The sky was light when the last dancers rolled up in their blankets under the spruce. Only the voyageurs were still awake, sitting around the fire and passing one of the endless bottles. René pumped them for more information on Duquet.

Duquet, they said, was clever. He had friends high in the fur company. He knew important men. He made side deals, keeping all the marten pelts for himself. He brought forbidden whiskey into the north and got the Indians too drunk to strike any but the feeblest and most disadvantageous bargains for their furs. “And Duquet is very strong, the strongest among us. He has great endurance.” To be strong was everything. Duquet was becoming a legend of the country.

René thought the seigneur had retired with his prize, but he now saw Monsieur Trépagny standing on the other side of the fire, listening. The flames paled in the brightening morning.

“This Duquet,” Monsieur Trépagny said, beginning quietly, but speaking in a quickening, sharpening tempo, his eyes bulging and beginning to roll. “Duquet? Would that be Duquet who signed a contract to work for me for three years?” His voice rose to a furious bellow. “Would that be the Duquet who ran away like a dog? Is that the Duquet of whom you speak?” He looked at his brothers.

Toussaint said nothing, his beard limp and stained, but Fernand rolled his wicked Trépagny eyes at his bridegroom brother and said “Ouais. The same. He told us you were cruel.”

“Ah,” said Monsieur Trépagny. “He does not yet know how cruel I can be. Do you return to Wobik now? I will go with you. I will have the dog’s skull. He will serve out his three years and we will see who is cruel.”

“Brother,” said Toussaint, “you would do well to leave Duquet alone. He is a dangerous man.” Monsieur Trépagny, goaded by this apostasy, screamed “Saddle my horse” at Elphège.

“Your pudding?” said Mari, holding out the cold pot. But René noticed how the seigneur glared at her as he rushed into his house.

In the few minutes it took Monsieur Trépagny to make his excuse to his new wife for his precipitous departure, Toussaint and Fernand ran to the riverbank, leapt into Monsieur Trépagny’s canoe and began to paddle like demons, forty-five paddle strokes a minute, downstream toward Wobik. Monsieur Trépagny’s horse was slower, and when he galloped into Wobik in late afternoon the traitorous brothers and Duquet were gone. The stolen canoe lay onshore, a marten pelt draped over the thwart—Duquet’s mocking signature.

The bridegroom, exhausted and furious, slumped on the deputy’s porch until that official returned home from the wedding, then swore out a warrant for Duquet’s capture and return.

“I will not rest until I get him and when I do he will suffer.”

Monsieur Bouchard was thrilled by this pledge of vengeance, like something in an old ballad, but he had no idea how he could execute the warrant and told Monsieur Trépagny so.

“It will happen,” gritted Trépagny through stained teeth.

Mari turned the cornmeal pudding into the embers where at first it gave off a savory smell and then the unpleasant odor of burning grain and sugar; she walked back to the old house. The grey jay that watched everything below waited a day until the ashes were cold and then pecked inquisitively at the burned lump. A few days later Chama discovered the bird’s carcass with legs twisted into a sailor’s knot, a very strange sight.

Monsieur Trépagny returned to his house in the forest and brooded for some weeks while preparing his expedition into the wilderness to capture Duquet. There was a strange turn in his mind that moved him to delay. He more and more left his new wife to herself and spent much time in his old house with Mari, whom he had forbidden to go back to the mission. Under his direction she cooked handsome dishes and every evening Monsieur Trépagny put on his fine clothes and carried them to Madame Trépagny. There was no cornmeal pudding. The husband and wife dined in silence in the elegant dining room and after dinner, when the maid had cleared the table, when Monsieur Trépagny had drunk a glass of brandy, he said, “Good evening, madame,” and returned to Mari. Nothing seemed changed. Mari and her children talked and laughed together in low voices as ever, and their pleasure in each other’s company irritated Trépagny, who hissed “Silence!” René wondered, too, what she had to say to them in such long ropes of talk, often accompanied by gestures and widened eyes. Months later he understood that she had been telling them the old Mi’kmaw stories, and into the warp of that heritage had interwoven the woof of complicated jokes and language games that gave her people so much pleasure. But Trépagny was sure that he was the butt of their half-smothered laughter, and his red nostrils flared and he demanded silence.

One morning, when René and Chama were cutting in the forest, the Spanish maid appeared and went to the old man. She handed him a letter, telling him Madame Trépagny wished him to carry it to the deputy in Wobik. Chama snorted and shook his head, but when she held up a gold coin he took the letter and put it in his shirt.

His beaver robe was empty for two nights, and it was dusk of the third day before René saw him again, carrying Monsieur Trépagny’s captured canoe, his excuse for the trip if his nephew should ask.

“What’s afoot?” asked René.

“Nothing good. Monsieur Bouchard turned the color of mud when he read that letter. He said he would come here tomorrow with the priest and consult with Madame and my nephew. It’s a bad business.”

6

Indian woman

Monsieur Bouchard and Père Perreault entered the clearing riding double on Monsieur Bouchard’s old plow horse. René, hauling a basket of fish, straightened up and stared. The visitors passed the storehouse without stopping, heading for Monsieur Trépagny’s marriage house. But that elevated gentleman, who had been working at his old forge, saw them through the open door and rushed out. “Where do you go, Monsieur Bouchard? Père Perreault, what do you here?”

The deputy wheeled around, dismounted and glared at Monsieur Trépagny. Père Perreault got down as well and held the reins.

Monsieur Bouchard said, “It is distressing that I find you here and not at your grand house with your lawful wife, Madame Trépagny. I have had a letter from the lady, who complains that you continue to live with the Indian woman, Mari, and are rarely seen at that wedding mansion in which she is lawfully ensconced and where you should be.”

Père Perreault spoke in a serious tone: “She wishes to return to her uncle’s house in France and demands the return of the rich dowry given you as you have broken your marriage pledge. You have behaved badly and the lady is within her rights. The uncle is a powerful man. He has taken up the matter and it will be a serious thing for you—and your position as seigneur. I ask you to accompany us to that house where she now awaits alleviation of her painful and insulting situation.”

Monsieur Trépagny followed them silently into the gloom of the west trail.

The day passed slowly. René told Chama and Mari what he had seen and heard. He thought a little smile flickered across Mari’s face. When she went inside Chama said, “This nephew should have proceeded in his search for Duquet. He should have stayed with that rich wife. Whenever there is an Indian woman involved there is trouble. His French wife is not the kind to shut her eyes.”

Night came and still they did not return. Chama said, “Claude will be begging her, he will grant anything she wishes rather than lose the money and the important position. I know him.”

Very early the next morning, as René and Chama were readying for another day of clearing trees, the three men, all in good humor, returned.

“Tell him at once,” said Père Perreault. “At once.” And they all looked at René.

“What? What is it?” he said. He had still not had a chance to talk to Monsieur Trépagny about his land, and he was afraid now that the seigneur had found a way to evade the responsibility.

“You will marry Mari,” said Monsieur Trépagny. “Immediately. Père Perreault is on hand to officiate.”

“No!” cried René. He whispered, not wishing to be overheard by Mari. “She is old. I do not want to marry her.” He had dreamed of a wife from one of the consignment ships with women from France, the King’s girls—les filles du Roi. A charming and shy young woman with blue eyes. “Also, you and Mari—”

“It was only a country marriage.” Père Perreault let the words slide out in his gentle way. “Just a country custom.”

“But no,” said René.

“You do not yet see reason,” said Monsieur Trépagny pleasantly. “She will help you make a house of your own on the land I grant you, and I will be very generous. I will grant you a double portion of land. You will have good workers to aid you—those Indian boys Elphège and Theotiste and that servant girl Renardette. Mari is a clever cook. She will warm you on winter nights. She is adept in curing illness. She has value. What more could you want?”

Mari herself was standing in the doorway, listening without expression. Père Perreault signed to her to come near. René thought furiously in several directions. But to himself he added another reason to Monsieur Trépagny’s list: with Mari at his side he could learn to read and write or, even better, depend on her to do whatever reading and writing was needed. The blue-eyed fille du roi of his dreams vanished. Again he felt himself caught in the sweeping current of events he was powerless to escape. What could he do against the commands of more important men? He nodded once, yes, he would marry Mari, an old Indian woman. So it was done.

In every life there are events that reshape one’s sense of existence. Afterward, all is different and the past is dimmed. For René the great blow had been the loss of Achille, his brother, whom he loved and most dreadfully missed. He came to New France to escape the loss, not realizing he would carry sorrow enclosed within him. The second event was the forced marriage to Mari.

Monsieur Trépagny made a formal assignment of land to René, granting him the old domus and workshop and the gardens but not the cow, as well as the clearing to the west that René coveted and the land with clear water springing from under a yellow birch. René was, in one stroke, a man of property. Père Perreault and Monsieur Bouchard left soon after the brief ceremony with Monsieur Trépagny’s signature on René’s land assignment.

Monsieur Trépagny spoke with casual sarcasm to Mari. “Madame Sel. Cook dinner as you always do and Chama will bring it to my lady wife and myself. After this evening her maid will prepare our food until we find a cook and servant. We will purchase a Pawnee or blackamoor slave or two from Kébec.” He walked westward into the forest.

Six woodcock had been hanging for days and had reached the hallucinogenic point of decay that Monsieur Trépagny savored. Mari roasted the birds, put them in a large basket, added a cold leg of venison, four portions of steamed sturgeon. René thought it was a supper the seigneur hardly deserved. Chama, who had become attentive to the Spanish maid, carried all of this in the oxcart, the cow tied behind. For their own supper Mari thumped on the table a platter of hot eels graced with the sour-grass sauce. She had baked in the morning and served a loaf of bread with the last of the butter—alas for the loss of the cow.