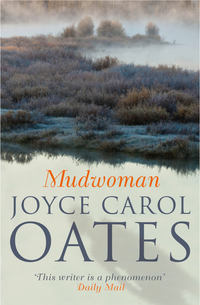

Mudwoman

“‘Just to stretch my legs.’ No other reason.”

She laughed. Her laughter was hopeful. A thin dew of fever-dreams on her forehead, oily and prickling in her armpits. And some sort of snarl in her hair. As if in the night she’d been dreaming of—something like this.

She would have time to shower before the reception—wouldn’t she? Change into her chic presidential clothes.

As a girl—a big husky girl—a girl-athlete—M.R. had sweated like any boy, sweat-rivulets running down her sides, a torment at the nape of her neck beneath the bushy-springy hair. And in her crotch—a snaggle of even denser hair, exerting a sort of appalled fascination to the bearer—who was “Meredith”—in dread of this snaggle of hair being somehow known by others; as there were years—middle school, high school—of anxiety that her body would smell in such a way to be detected by others.

Of course, it had. Many times probably. For what could a husky girl do? Warm airless classroom-hours, sturdy thighs sticking/slapping together if you were not very careful.

As on certain days of the month, anxiety rose like the red column of mercury in a thermometer, in heat.

Having her period. Poor Meredith!

Everything shows in her face. Funny!

Early that morning before Carlos arrived—for M.R. had slept only intermittently through the night—she’d showered, of course, shampooed her hair. So long ago, seemed like another day.

And so another shower, back at the hotel. When she returned.

On the interstate M.R. was making good time in the compact little vehicle. Her speed held steady at just above sixty miles an hour which was a safe speed, even a cautious speed amid so many larger vehicles hurtling past her in the left lane as if with snorts of derision.

But—the beauty of this landscape! It required going away, and returning, to truly see it.

Farmland, hills. Wide swaths of farmland—cornfields, wheat—now harvested—rising in hills to the horizon. She caught her breath—those flame-flashes of sumac dark-red, fiery-orange by the roadside—amid darker evergreens, deciduous trees whose leaves hadn’t—yet—begun to die.

Already she was beyond Bone Plain Road, Frozen Ocean State Park. Passing signs for Boontown, Forestport, Poland and Cold Brook—names not yet familiar to her from her girlhood in Beechum County.

These precious hours! If her parents knew, they’d have wanted to see her—they’d have been willing to drive to Ithaca for the evening.

They’d have wanted to hear her keynote address. For they were so very proud of her. And they loved her. And saw so little of her since she’d left Carthage on that remarkable scholarship to Cornell, it must have perplexed them.

“I should have. Why didn’t I!”

It was as if M.R. had not thought of the possibility at all. As if a part of her brain had ceased functioning.

That peculiar sort of blindness/amnesia in which objects simply vanish as they pass into the area monitored by the damaged brain. Not that one forgets but that experience itself has been blocked.

Now that M.R. had assistants, it was no trouble to make such arrangements. At the hotel, for instance. Or, if the conference hotel was booked solid, at another local hotel. Audrey would have been delighted to book a room for M.R.’s parents.

M.R.’s lover had heard her speak in public several times. He’d been surprised—impressed—by her ease before a large audience, when M.R. was so frequently uneasy in his company.

Well, not uneasy—excited. M.R. was frequently so excited in his company.

She couldn’t bring herself to confess to her (secret) lover that intimacy with him was so precious to her, it was a strain to which she hadn’t yet become accustomed. She’d said with a smile No speaker makes eye contact with his audience. The larger the audience, the easier. That is the secret.

Her lover imagined her a far more composed and self-reliant individual than she was. It had long been a fiction of their relationship, that M.R. didn’t “need” a man in her life; she was of a newer, more liberated generation—for her lover was her senior by fourteen years, and often remarked upon this fact as if to absolve himself of any candidacy as the husband of a girl “so young.” Also, Andre was enmeshed in a painful marriage he liked to describe as resembling Laocoön and sons in the coils of the terrible sea-serpents.

M.R. laughed aloud. For Andre Litovik was so very funny, you might forget that his humor frequently masked a truth or a motive not-so-funny.

“Oh—God …”

Powerful air-suction from a passing/speeding trailer-truck made M.R.’s compact vehicle shudder. The trucker must have been driving at eighty miles an hour. M.R. braked her car, alarmed and frightened.

She’d been daydreaming, and not concentrating on her driving. She’d felt her mind drift.

Better to exit the interstate onto a state highway. This was safer, if slower. Through acres of steeply hilly farmland she drove into Cortland County, and she drove into Madison County, and she drove into Herkimer County and into the foothills of the Adirondacks and at last into Beechum County where mountain peaks covered in evergreens stretched hazy and sawtoothed to the horizon like receding and diminishing dreams.

She’d planned to drive north for only an hour and a half before turning around but decided now that a few minutes more—a few miles more—would do no harm.

Wherever she found herself at—4:30 P.M.?—she would stop at once, turn her car around and head back to Ithaca.

This was likely the first time in months that no one on M.R.’s staff knew where she was, at such an hour of a weekday. No friends knew, no colleagues. M.R. had passed into the blind side of the brain, she’d become invisible.

Was this a good thing, or—not so good? Both her parents had praised her as a girl for her maturity, her sense of “responsibility.” But this was something different, a mere interlude.

This was something different: no one would ever know.

She’d turned off her cell phone. More practical to take messages and answer them in sequence.

And what relief, to have left her laptop behind on the hotel bed! She was attached to the thing like a colostomy bag. Her senses reacted in panic if it appeared to be malfunctioning for just a few minutes. A flurry of e-mails buzzing in her wake like angry bees.

Belatedly M.R. remembered—she was supposed to meet with a prominent educator now chairing a national committee on bioethics who’d been asked to invite M.R. to join the committee. This was a committee M.R. wanted to join—nothing seemed to her more crucial than establishing guidelines on bioethics—yet somehow, she’d forgotten. In her haste to rent a car and drive up into Beechum County, she’d forgotten. And M.R. had scheduled their meeting-time herself—just before the reception, at 5 P.M.

She might have called the man to postpone their meeting to the next day but she didn’t have his cell phone number. Nor did she want to call her assistant Audrey to place the call for her for Audrey would naturally inquire where M.R. was and M.R. could not possibly tell her—“Just crossing the Black Snake River, up in Beechum County.”

Audrey would have been speechless. Audrey would have thought that M.R. must be joking.

Now in Beechum County M.R. switched on the car radio. She hoped to tune in to a Watertown station—WWTX. Once an NPR affiliate but now M.R. couldn’t locate it on the dial only just deafening patches of rock music and advertisements—the detritus of America.

On one FM station there appeared to be news—news from Washington—but static swept it away like ribald laughter.

News from Washington—but the U.S. Congress wouldn’t yet be voting on the war resolution, would it? This was too soon. There had to be days yet of debate.

M.R. couldn’t quite believe that legislators in Washington would authorize the bellicose Republican president to wage war against Iraq—this would be madness! The U.S. hadn’t entirely recovered from the debacle of the Vietnam War of which little ambiguity remained—the war had been a terrible mistake. Still, excited war rumors in the media—even the more liberal media like the New York Times—flared and rippled like wildfire in dried brush. There was a terrible thrillingness to the possibility of war.

It was astonishing how effectively the administration had lied to convince the majority of the American public that there was a direct link between Iraq and the terrorist attacks of 9/11. For since that catastrophic episode a near-palpable toxic-cloud was accumulating over the country, a gradual darkening of logic—an impatience with logic.

Madness! M.R. could not think of it without beginning to tremble.

She was an ethicist: a professional. It was criminal, it was self-destructive, it was cruel, stupid, quixotic—unethical: waging war on such flimsy pretexts.

What was the appeal of war?—the appeal of a paroxysm of sustained and collective violence repeated endlessly, from the earliest prehistory until the present time? It was not enough to say Men are bred to war, men are warriors—men must perform their role as warriors. It was not enough to say Humankind is self-destructive, damned. Of all the species, damned.

As a liberal, as an educator, M.R. did not believe in such primitive determinism. She did not believe in genetic determinism at all.

Very likely she had young relatives scattered through Beechum County who were in the National Guard or in a branch of the armed services. Some might even now be stationed in the Middle East awaiting deployment to battle, as in the Gulf War of some years ago. Like the more southern Appalachian region Beechum County was the sort of economically depressed rural-America that provided fodder for the military machine.

M.R.’s immediate family—Agatha and Konrad—were Quakers, if not “active” in the nearest Friends’ congregation, which was some distance from Carthage. (“Too lazy to drive,” Konrad said. “You can ‘Quaker’ at any time and any place.”) None of the other Neukirchens were Quakers and certainly none were pacifists like Konrad who’d been granted the status of conscientious objector during the Korean War and instead of being incarcerated in a federal prison was allowed to work in a VA hospital in Baltimore.

Konrad was a kindly man, short and squat as a fireplug and fierce in declaring that if somehow he’d found himself in the army—in combat—he could never fire at any “enemy.” He could not even hold a gun, point a gun at anyone.

M.R. smiled, recalling her father. She was recalling Konrad not as he was at the present time—an aging ailing man—but as he’d been in her earliest memories, in the mid-and late 1960s.

The one thing they can’t make you do is kill another person. They can’t even make you hate another person.

There was a sign—CARTHAGE 78 MILES. But M.R. could not drive to Carthage today.

Uneasily she was thinking—is it time to turn back? Some instinct kept her from checking the time….

How strange she was feeling! This sensation she’d felt as a girl inching out—with other, older children—onto the frozen river; so darkly swift-flowing a river, like a black snake with glittering scales, that water froze only at shore and continued to rush along at the center of the stream.

Unmistakably, there was a thrill to this. Daring and reckless the older boys crept out onto the ice, toward the unfrozen center. Younger children stayed behind out of timidity.

You must not let them entice you, Meredith! If you are injured they will run away and abandon you for that is their kind—they are cruel, can’t help themselves for their God is a God of conquest and wrath and not a God of love.

There was a dislike, a resentment of Meredith’s parents—not to their faces but behind their backs—for Konrad’s unmanly pacifism. For Beechum County was a gun culture. Hunters, warriors.

M.R. felt a mild headache coming on. She hadn’t eaten since early that morning and then at her desk at home, answering e-mails.

Solitary mealtimes are not very pleasurable. Solitary mealtimes are best avoided.

The deficiency of philosophy is that it has no stomach, no guts. In all of classic philosophy not a single pulsebeat of feeling.

Oh why hadn’t she invited Agatha and Konrad to Ithaca for this evening! It would have been so easy to have done, and would have meant so much to them.

M.R. loved her parents but often seemed to forget them. Like clouds sailing overhead, they were—snowy-white clouds of surpassing and unearthly beauty at which no one thinks to look.

“I will do better. I will try harder. I hope they will forget me.”

She meant forgive of course. Not forget.

In fact she was—just now—crossing the Black Snake River. The wrought-iron truss bridge vibrated beneath the lightweight Toyota. The river was thirty or more feet below the bridge, rushing like something demented. Wheels—spirals—of light—like defects in the eye. You could imagine a giant serpent in that molten liquid—lifting its head, tawny eyes and fanged jaws.

Look again, the serpent has vanished beneath the water’s surface.

Farther to the west, at Carthage, in layers of crusted shale there were fossils M.R. had searched for, as a girl. Ancient crustaceans, long-extinct fish. Her biology teacher had sent her out: he’d identified the fossils for her. M.R. had drawn them in her notebook, with particular care.

A string of A-pluses attached to Meredith Neukirchen like a comet’s long tail.

Here the river’s shore was less rocky, more marshy. The river did not appear to be the river of her girlhood and yet—it was strangely familiar to her, like the serpent’s head.

Off the bridge ramp was a sign for RAPIDS—5 MILES. SLABTOWN—11 MILES. RIVIERE-DU-LOUP—18 MILES. In the near distance Mount Moriah—one of the highest peaks in the southern Adirondacks—and beyond, shadowy peaks whose names M.R. couldn’t recall with certainty: Mount Provenance, Mount Hammer? Mount Marcy? It was geology—nineteenth-century geology—that had first shaken the Christian creation-myth so deeply entrenched in Europe, and in the blood-steeped soil of Europe, you would never think it might be extirpated like rotted roots; eruptions of human certainty like eruptions of volcanic lava scouring everything in its path. For what was the earth but a mass of roiling lava—not a “created” thing at all.

Within a few decades, the old faith was shaken utterly. All was devastation.

Except, as Nietzsche so shrewdly observed, the devastation was ignored. Denied. Knowledge of Earth’s position in the universe had entered the blind-visual field of neglect.

She would not be a party to such denial, such blindness. She, empowered as the first woman president of a great university, would speak the truth as she saw it.

For in her vanity she wished to align herself with the great truth-tellers—not with those who spoke to placate.

In high school M.R. had been drawn to geology as to other sciences but in subsequent years her passion for the abstract—for philosophy—“ethics”—had driven out the hard concrete names like irreducible ores—igneous, sedimentary, metamorphic.

Science is another name for God-seeking, the Neukirchens had assured her. Their Quaker faith was so very wide, vast, all-encompassing—a Sargasso Sea without boundaries and without a Savior.

M.R. dared not glance at the dashboard clock. It was time for her to turn back, she knew.

She was passing trailer villages, small asphalt-sided houses, semi-abandoned farmhouses and barns. She was passing the Old Dutch Road—was this familiar?—and the Sandusky Road. The narrow Black River Road curved dangerously close to the river. On that side, the shoulder had been eaten away by erosion. On the farther shore was a curious steep step-ladder-like hill or small mountain near-bare of vegetation from which gigantic boulders seem to have loosed and fallen into the river. There was the look of an ancient landscape shaken, broken. Yet a powerful beauty in these broken shapes.

A sharp pain struck between her shoulder blades like a stinging insect for she’d been tensing up, driving. Leaning forward gripping the steering wheel in both hands as if fearing the wheel might get away from her.

He’d said to her—her (secret) lover—Eternity hasn’t a damn thing to do with time—but he’d been joking, he had not meant to be cruel or mocking and she had kissed his mouth, daring to kiss his mouth that was only just barely hers to kiss.

More mysteriously he’d said Earth-time is a way of preventing everything happening at once.

Did he mean—what? M.R. wasn’t sure.

Telling a story, you must lay out “events”—in a chronological sequence. Or rather, you must establish a chronological sequence, so that you know what your story is, and can “tell” it.

Only in time, calendar-time and clock-time, is there chronology. Otherwise—an entire life is but a nanosecond, as swiftly ended as it began, and everything has happened at once.

Possibly, this was what Andre meant. His field was galaxy evolution and star formation in galaxies—his boyhood obsession had been a hope of “mapping” the Universe.

M.R. had had few lovers—very few. For men were not naturally—she supposed, sexually—attracted to her. Her weakness was for men of exceptional intellect—at least, intelligence greater than her own. So that she would not be required to mask her own.

The sorrow was, such men seemed to have been, through her life, invariably older than she. And some of them cynical. And some worn like old gloves, scuffed boots. Most were married and some twice-or even thrice-married.

She did want to be married! One day.

She did want to marry Andre Litovik.

He’d tried to discourage her from accepting the presidency of the University. She’d had a sense that he was fearing his girl-Amazon might drift from him after all.

If truly he loved her—he’d have been hopeful for her, proud of her.

Or maybe: even an exceptional man has difficulty feeling pride in an exceptional woman.

M.R. tried to determine where she was. Ever more uneasily she was conscious of time passing.

Ready you must be readied. It is time.

A sign for SPRAGG 7 MILES. SLABTOWN 13 MILES. A sign for Star Lake, in the opposite direction—66 MILES.

Spragg—Slabtown—Star Lake. M.R. had heard of Star Lake, she thought—but not the others, so oddly named.

Abruptly then she came to a barrier in the road.

DETOUR

ROAD OUT NEXT 3 MILES

You could see how beyond the barrier a stretch of road had collapsed into the Black Snake River. Quickly M.R. braked the Toyota to a stop—the earth-slide was shocking to see, like a physical deformity.

“Oh! Damn.”

She was disappointed—this would slow her down.

She was thinking how swiftly it must have happened: the road caving in beneath a moving vehicle, a car, a truck—a school bus?—plunging into the river, trapped and terrified and no one to witness the horror. Not likely that the road had simply collapsed beneath its own weight.

Death by (sheer) accident. Surely this was the most merciful of deaths!

Death at the hands of another: the cruelest.

Death by the hands of another who is known to you, close as a heartbeat: the very cruelest.

By the look of the fallen-away road, vines and briars growing in cracks, a tangle of sumac and stunted trees, the river road had not collapsed recently. Beechum County had no money for the repair of so remote a road: the detour had become perpetual.

Like a curious child—for one is always drawn to DETOUR as to NO TRESPASSING: DANGER—M.R. turned her car onto a narrow side road: Mill Run. Though of course, the sensible thing would be to turn back.

Was Mill Run even paved? Or covered in gravel, that had long since worn away? The single-lane road led into the countryside that appeared to be low-lying, marshy; no farmland here but a sort of no-man’s-land, uninhabited.

At a careful speed M.R. drove along the rutted road. She was a good driver—intent upon avoiding potholes. She knew how a tire can be torn by a sudden sharp declivity; she could not risk a flat tire at this time.

M.R. was one who’d learned to change tires, as a girl. There was the sense that M.R. had better learn to fend for herself.

In fact there had been inhabitants along the Mill Run Road, and not too long ago—an abandoned house, set back in a field like a gaunt and etiolated elder; a Sunoco station amid a junked-car lot, that appeared to be closed; and an adjoining café where a faded sign rattled in the wind—BLACK RIVER CAFÉ.

Both the Sunoco station and the café were boarded up. Just outside the café was a pickup truck shorn of wheels. M.R. might have turned into the parking lot here but—so strangely—found herself continuing forward as if drawn by an irresistible momentum.

She was smiling—was she? Her brain, ordinarily so active, hyper-active as a hive of shaken hornets, was struck blank in anticipation.

In hilly countryside, foothills and densely wooded mountains, you can see the sky only in patches—M.R. had glimpses of a vague blurred blue and twists of cloud like soiled bandages. She was driving in odd rushes and jolts pressing her foot on the gas pedal and releasing it—she was hoping not to be surprised by whatever lay ahead and yet, she was surprised—shocked: “Oh God!”

For there was a child lying at the side of the road—a small figure lying at the side of the road broken, discarded. The Toyota veered, plunged off the road into a ditch.

Unthinking M.R. turned the wheel to avoid the child. There came a sickening thud, the jolt of the vehicle at a sharp angle in the ditch—the front left wheel and the rear left wheel.

So quickly it had happened! M.R.’s heart lurched in her chest. She fumbled to open the door, and to extract herself from the seat belt. The car engine was still on—a violent peeping had begun. She’d thought it had been a child at the roadside but of course—she saw now—it was a doll.

Mill Run Road. Once, there must have been a mill of some sort in this vicinity. Now, all was wilderness. Or had reverted to wilderness. The road was a sort of open landfill used for dumping—in the ditch was a mangled and filthy mattress, a refrigerator with a door agape like a mouth, broken plastic toys, a man’s boot.

Grunting with effort M.R. managed to climb—to crawl—out of the Toyota. Then she had to lean back inside, to turn off the ignition—a wild thought came to her, the car might explode. Her fingers fumbled the keys—the keys fell onto the car floor.

She saw—it wasn’t a doll either at the roadside, only just a child’s clothing stiff with filth. A faded-pink sweater and on its front tiny embroidered roses.

And a child’s sneaker. So small!

Tangled with the child’s sweater was something white, cotton—underpants?—stiff with mud, stained. And socks, white cotton socks. And in the underbrush nearby the remains of a kitchen table with a simulated-maple Formica top. Rural America, filling up with trash.

An entire household dumped out on the Mill Run Road! Not a happy story.

M.R. stooped to inspect the refrigerator. Of course it was empty—the shelves were rusted, badly battered. There was a smell. A sensation of such unease—oppression—came over her, she had to turn away.

“And now—what?”

She could call AAA—her cell phone was in the car. But probably she could maneuver the Toyota out of the ditch herself for the ditch wasn’t very deep.

Except—what time was it?

Staring at her watch. Trying to calculate. Was it already past 4:30 P.M.—nearly 5 P.M.? This was unexpectedly late! Mid-October and the sun slanting in the sky and dusk coming on.

This side of the Black Snake River were stretches of marshland, mudflats. She’d been smelling mud. You could see that the river often overran its banks here. There was a harsh brackish smell as of rancid water and rotted things.

Staring at her watch which was a small elegant gold watch inscribed with the name and heraldic insignia of a New England liberal arts college for women. It had been given to M.R. to commemorate her having received from the college an honorary doctorate in humane letters and shortly thereafter, an invitation to interview for its presidency. She’d been thirty-six at the time. She’d been dean of the faculty at the University at the time. Graciously she’d declined. She did not say I am so grateful but no—it isn’t likely that I would accept a position at a women’s college.