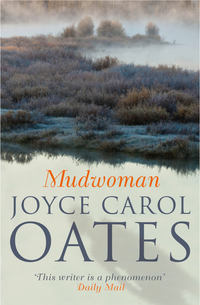

Mudwoman

Or—It isn’t likely that I would accept a position at any university other than a major research university. That is not M. R. Neukirchen’s plan.

Amid the cast-off household litter was a strip of rotted tarpaulin.

M.R. pulled it loose, dragged it to the Toyota to place beneath the wheels on the driver’s side, that were mired in mud. This was good! This was good luck! Awkwardly then she crawled back into the badly tilted car, located the keys on the floor mat, and managed to start the engine—eased the car forward a few inches, let it rock back; eased it again forward, and let it rock back; at first the wheels spun, then began to take hold. The car moved, jerked spasmodically; in another minute or two she would have eased the Toyota back up onto the road except—the rotted tarpaulin must have given way, the wheels spun frantically.

“God damn.”

M.R. reached for the cell phone, that had fallen to the floor. Tried to call AAA but the phone was unreceptive.

If only she’d thought to call her assistant a half hour ago—the cell phone might have worked then. Just to allow the (anxious?) young woman to know I may be late for the reception. A few minutes late. But I will not be late for the dinner. I will not be late for my talk of course.

She would have spoken to Audrey in her usual bright brisk manner that did not invite interruptions. It was a bright brisk manner that did not invite murmurs of commiseration. She would have said, if Audrey had expressed concern for her, Of course, I’m fine! Good-bye for now.

She was hiking along the road with the cell phone in her hand. Repeatedly she tried to activate it but the damned thing remained dead.

Useless plastic, dead!

If she ascended to higher ground? Would the phone be more likely to work? Or—was this a ridiculous notion, desperate?

“I am not desperate. Not yet.”

Amid the mudflats was a sort of peninsula, a spit of land raised about three feet, very likely man-made, like a dam; M.R. climbed up onto it. She was a strong woman, her legs and thighs were hard with muscle beneath the soft, just slightly flabby female flesh; she made an effort to swim, hike, run, walk—she “worked out” in the University gym; still, she quickly became breathless, panting. For there was something very oppressive about this place—the acres of mudflats, the smell. Even on raised ground she was walking in mud—her nice shoes, mud-splattered. Her feet were wet.

She thought I must turn back. As soon as I can.

She thought I will know what to do—this can be made right.

Staring at her watch trying to calculate but her mind wasn’t working with its usual efficiency. And her eyes—was something wrong with her eyes?

The reception would begin at—was it 6 P.M.? But M.R. wouldn’t need to arrive promptly at 6 P.M. M.R. wouldn’t have to attend the reception at all. Such events were hardly crucial. And the dinner—was the dinner at 7:30 P.M.? She would hurry to the table which would be the head table in the enormous banquet room—she would murmur an apology—she could explain that she’d had to drive somewhere, unavoidably—her car had broken down returning.

Stress, overwork the doctor had told her. Hours at the computer and when she glanced up her vision was distorted and she had to blink, squint to bring the world into some sort of focus.

How faraway that world—there could be no direct route to that world, from the Mill Run Road.

A crouched figure. Bearded face, astonished eyes. Slung over his shoulder a half-dozen animal traps. With a gloved hand prodding at—whatever it was in the mud.

“Hello? Is someone …?”

She was making her way along the edge of a makeshift dam. It was a dam comprised of boulders and rocks and it had acquired over the years a sort of mortar of broken and rotted tree limbs and even animal carcasses and skeletons. Everywhere the mudflats stretched, everywhere cattails and rushes grew in profusion. There were trees choked with vines. Dead trees, hollow tree-trunks. The pond was covered in algae bright-green as neon that looked as if it were quivering with microscopic life and where the water was clear the pebble-sky was reflected like darting eyes. She was staring at the farther shore where she’d seen something move—she thought she’d seen something move. A flurry of dragonflies, flash of birds’ wings. Bursts of autumn foliage like strokes of paint and deciduous trees looking flat as cutouts. She waited and saw nothing. And in the mudflats stretching on all sides nothing except cattails, rushes stirred by the wind.

She was thinking of something her (secret) lover had once said—There is no truth except perspective. There are no truths except relations. She had seemed to know what he’d meant at the time—he’d meant something matter-of-fact yet intimate, even sexual; she was quick to agree with whatever her lover said in the hope that someday, sometime she would see how self-evident it was and how crucial for her to have agreed at the time.

Thinking There is a position, a perspective here. This spit of land upon which I can walk, stand; from which I can see that I am already returned to my other life, I have not been harmed and will have begun to forget.

Thinking This is all past, in some future time. I will look back, I will have walked right out of it. I will have begun to forget.

The spit of land—a kind of raised peninsula—the ruin of an old mill. In the tall spiky weeds remnants of lumber. Shattered concrete blocks. She was limping—she’d turned her ankle. She was very tired. She had not slept for a very long time. In the president’s house she was so lonely! Her (secret) lover had not come to visit her. Her (secret) lover had not come to visit her since she’d moved into the president’s house and there was no plan for him to visit—yet.

In the president’s house which was an historic landmark dating to Colonial times M.R. had her own private quarters on the second floor. Still, the bed in which she slept in the president’s house was an antique four-poster bed of the 1870s and it was not a bed M.R. would have chosen for herself though it was not so uncomfortable a bed that M.R. wished to have it moved out and another bed moved in.

For his back, Andre required a hard mattress. At least, the mattress in M.R.’s bed was that.

At the end of the peninsula there was—nothing. Mudflats, desiccated trees. In the Adirondacks, acid rain had been falling for years—parts of the vast forest were dying.

“Hello?”

Strange to be calling out when clearly no one was there to hear. M.R.’s uplifted hand in a ghost-greeting.

He’d been a trapper—the bearded man. Hauling cruel-jawed iron traps over his shoulder. Muskrats, rabbits. Squirrels. His prey was small furry creatures. Hideous deaths in the iron traps, you did not want to think about it.

Hey! Little girl—?

She turned back. Nothing lay ahead.

Retracing her steps. Her footprints in the mud. Like a drunken person, unsteady on her feet. She was feeling oddly excited. Despite her tiredness, excited.

She returned to the littered roadway—there, the child’s clothing she’d mistaken so foolishly for a doll, or a child. There, the Toyota at its sharp tilt in the ditch. Within minutes a tow truck could haul it out, if she could contact a garage—so far as she could see the vehicle hadn’t been seriously damaged.

Possibly, M.R. wouldn’t need to report the accident to the rental company. For it had not been an “accident” really—no other vehicle had been involved.

She walked on, not certain where she was headed. The sky was darkening to dusk. Shadows lifted from the earth. She saw lights ahead—lights?—the gas station, the café—to her surprise and relief, these appeared to be open.

There was a crunch of gravel. A vehicle was just departing, in the other direction. Other vehicles were parked in the lot. In the café were lights, voices.

M.R. couldn’t believe her good luck! She would have liked to cry with sheer relief. Yet a part of her brain thinking calmly Of course. This has happened before. You will know what to do.

At a gas pump stood an attendant in soiled bib overalls, shirtless, watching her approach. He was a fattish man with snarled hair, a sly fox-face, watching her approach. Uneasily M.R. wondered—would the attendant speak to her, or would she speak to him, first? She was trying not to limp. Her leather shoes were hurting her feet. She didn’t want a stranger’s sympathy, still less a stranger’s curiosity.

“Ma’am! Somethin’ happen to ya car?”

There was a smirking sort of sympathy here. M.R. felt her face heat with blood.

She explained that her car had broken down about a mile away. That is—her car was partway in a ditch. Apologetically she said: “I could almost get it out by myself—the ditch isn’t deep. But …”

How pathetic this sounded! No wonder the attendant stared at her rudely.

“Ma’am—you look familiar. You’re from around here?”

“No. I’m not.”

“Yes, I know you, ma’am. Your face.”

M.R. laughed, annoyed. “I don’t think so. No.”

Now came the sly fox-smile. “You’re from right around here, ma’am, eh? Hey sure—I know you.”

“What do you mean? You know—me? My name?”

“Kraeck. That your name?”

“‘Kraeck.’ I don’t think so.”

“You look like her.”

M.R. didn’t care for this exchange. The attendant was a large burly man of late middle age. His manner was both familiar and threatening. He was approaching M.R. as if to get a better look at her and M.R. instinctively stepped back and there came to her a sensation of alarm, arousal—she steeled herself for the man’s touch—he would grip her face in his roughened hands, to peer at her.

“You sure do look like someone I know. I mean—used to know.”

M.R. smiled. M.R. was annoyed but M.R. knew to smile. Reasonably she said: “I don’t think so, really. I live hundreds of miles away.”

“Kraeck was her name. You look like her—them.”

“Yes—you said. But …”

Kraeck. She had never heard it before. What a singularly ugly name!

M.R. might have told the man that she’d been born in Carthage, in fact—maybe somehow he’d known her, he’d seen her, in Carthage. Maybe that was an explanation. There was a considerable difference between the small city of Carthage and this desolate part of the Adirondacks. But M.R. was reluctant to speak with this disagreeable individual any more than she had to speak with him for she could see that he was listening keenly to her voice, he’d detected her upstate New York accent M.R. had hoped she’d overcome, that so resembled his own.

“Excuse me …”

Badly M.R. had to use a restroom. She left the fox-faced attendant staring rudely at her and climbed the steps to the café.

It was wonderful how the sign that had appeared so faded, derelict, was now lighted: BLACK RIVER CAFÉ.

Inside was a long counter, or a bar—several men standing at the bar—a number of tables of which less than half were occupied—winking lights: neon advertisements for beer, ale. The air was hazy with smoke. A TV above the bar, quick-darting images like fish. M.R. wiped at her eyes for there was a blurred look to the interior of the Black River Café as if it had been hastily assembled. Windows with glass that appeared to be opaque. Pictures, glossy magazine cutouts on the walls that were in fact blank. From the TV came a high-pitched percussive sort of music like wind chimes, amplified. M.R. was smelling something rich, yeasty, wonderful—baking bread? Pie? Homemade pie? Her mouth flooded with saliva, she was weak with hunger.

“Ma’am! Come in here. You look cold. Hungry.”

Out of the kitchen came a heavyset woman with a large round muffin-face creased in a smile. She wore a man’s red-plaid flannel shirt and brown corduroy slacks and over this a stained gingham apron. She was holding the kitchen door open, for M.R. to join her.

“Ma’am—mind if I say—you lookin’ like you had some kind a shock. You better come here.”

M.R. smiled, uncertainly. With a touch of her warm hand the heavyset woman drew M.R. forward as the men at the bar stared frankly.

Maybe—they liked what they saw. They approved of the girl-Amazon in city clothes, disheveled.

The woman was as tall as M.R.—in fact taller. Her hair was knotted and coiled about her head—a wan, faded gold like retreating sunshine. Her wide-set eyes were lighted like coins. And that wide, wet smile.

“Good you got here, ma’am. Out on that road after dark—you’d get lost fast.”

“Oh yes! Thank you.”

M.R. was dazed with gratitude. She felt like a drowning swimmer who has been hauled ashore.

In the kitchen, M.R. was given a chair to sit in. It was a familiar chair, this was comforting. The paint worn in a certain pattern on the back—the wicker seat beginning to buckle. And just in time for her knees had become weak.

Another comfort, the smell of baked goods. Simmering food, some kind of stew, on the stove. Like a sudden flame a frantic hunger was released in M.R.

“Hel-lo! Wel-come!”

“Ma’am! Wel-come.”

There were others in the kitchen, warmly greeting M.R. She could not see their faces clearly but believed that they were relatives of the older woman.

There came a bowl of dark glistening soup, placed steaming before M.R. She supposed it was some kind of beef soup, or lamb—mutton?—globules of grease on the surface but M.R. was too hungry to be repelled. Her lips were soon coated with grease, there was no napkin with which she might wipe her face. She’d become so civilized, it was awkward for her to eat without a napkin in her lap—but there were no napkins here.

“Good, eh? More?”

Yes, it was good. Yes, M.R. would have more.

She was seated at a familiar table—Formica-topped, simulated maple, with battered legs. The air in the kitchen was warm, close, humid. On the gas-burner stove were many pots and pans. On another table were fresh-baked muffins, whole grain bread, pies. These were pies with thick crusts and sugary-gluey insides. Apple pies, cherry pies.

A bottle of beer. Bottles of beer. A hand lifted the bottle, poured the foaming dark liquid into a glass. M.R. drank.

So thirsty! So hungry! Her eyes welled with tears of childish gratitude.

The heavyset woman served her. The heavyset woman had enormous breasts to her waist. The heavyset woman had a coarse flushed skin and sympathetic eyes. Her crown of braids made her appear regal yet you knew—you could not coerce this woman.

When others—men, boys—tried to push into the kitchen to peer at M.R. in her rumpled and mud-stained clothes, the heavyset woman shooed them away. Laughing saying, Yall go away get the hell out noner your business here.

M.R. was eating so greedily, soup spilled onto the front of her jacket.

Her hands shook. Beer in her nostrils making her cough, choke.

She’d had too much to drink, and to eat. Too quickly. Laughing became coughing and coughing became choking and the heavyset woman thumped her between the shoulder blades with a fist.

It was the TV—or, a jukebox—loud percussive music. She could not hear the music, so loud. Something was entering her—lights?—like glinting blades. She wasn’t drunk but a wild drunken elation swept over her, she was so very grateful trying to explain to the heavyset woman that she had never tasted food so wonderful.

Thinking I have never been so happy.

For it was revealed to M.R. that there were such places—(secret) places—to which she could retreat. (Secret) places not known even to her that would comfort her in times of danger. A sudden expansion of being as if something had gotten inside her tight-braided brain and pumped air and light into it—fire, wind—laughter—music.

Hel-lo. Hel-lo. Hel-lo!

Don’t I know you?

Hey sure—sure I do. And you know me.

Feeling so very relieved. So very happy. A warmth spread in her heart. Clumsily M.R. tried to stand, to step into the embrace of the heavyset woman—press her face against the woman’s large warm spongy breasts and hide inside the warm spongy fleshy arms.

You know—you are safe here.

Waiting for you—here.

Jewell!—Jedina. We are waiting for you—here.

Yet there was something wrong for the heavyset woman hadn’t embraced her as M.R. had expected—instead the heavyset woman pushed M.R. away as you might push away an importunate child not in anger or annoyance or even impatience but simply because at that moment the importunate child isn’t wanted. There was a rebuke here, M.R. did not want to consider. She was thinking I must pay. I must leave a tip. None of this can be free. She was fumbling with her wallet—she’d misplaced her leather handbag but somehow, she had her wallet. And she was trying to see her watch. The numerals were blurred. In fact there were no hands on the watch-face to indicate the time. Let me see that, ma’am. Deftly the watch was removed from her wrist—she wanted to protest but could not. And her wallet—her wallet was taken from her. In its place she was given something to drink that was burning-hot. Was it whiskey? Not beer but whiskey? Her throat burned, her eyes smarted with tears. That’ll speak to you, ma’am, eh?—a man’s voice, bemused. There was laughter in the café—the laughter of men, boys—not mocking laughter—(she wanted to think)—but genial laughter—for they’d pushed into the kitchen after all.

Ma’am where’re you from?—for her voice so resembles theirs. Ma’am where’re you going?—for despite her clothes she’s one of them, their staring eyes can see.

Her heavy head is resting on her crossed arms. And the side of her face against the sticky tabletop. So strange that her breasts hang loose to be crushed against the tabletop. The rude laughter has faded. So tired! Her eyes are shut, she is sinking, falling. There’s a scraping of chair legs against the floor that sound unfriendly. A hand, or a fist, lightly taps her shoulder.

“Ma’am. We’re closing now.”

Mudgirl Saved by the King of the Crows.

April 1965

In Beechum County it would be told—told and retold—how Mudgirl was saved by the King of the Crows.

How in the vast mudflats beside the Black Snake River in that desolate region of the southern Adirondacks there were a thousand crows and of these thousand crows the largest and fiercest and most sleek-black-feathered was the King of the Crows.

How the King of the Crows had observed the cruel behavior of the woman half-dragging half-carrying a weeping child out into the mudflats to be thrown down into the mud soft-sinking as quicksand and left the child alone there to die in that terrible place.

And the King of the Crows flew overhead in vehement protest flapping his wide wings and shrieking at the retreating woman now shielding her face with her arms against the wrath of the King of the Crows in pursuit of her like some ancient heraldic bird-beast in the service of a savage God.

How in the mists of dawn less than a mile from the place where the child had been abandoned to die there was a trapper making the rounds of his traps along the Black Snake River and it was this trapper whom the King of the Crows summoned to save the child lying stunned in shock and barely breathing in the mudflat like discarded trash.

Come! S’ttisss!

Suttis Coldham making the rounds of the Coldham traps as near to dawn as he could before predators—coyotes, black bears, bobcats—tore their prey from the jaws of the traps and devoured them alive weakened and unable to defend themselves.

Beaver, muskrat, mink, fox and lynx and raccoons the Coldhams trapped in all seasons. What was legal or not-legal—what was listed as endangered—did not count much with the Coldhams. For in this desolate region of Beechum County in the craggy foothills of the Adirondacks there were likely to be fewer human beings per acre than there were bobcats—the bobcat being the shyest and most solitary of Adirondack creatures.

The Coldhams were an old family in Beechum County having settled in pre-Revolutionary times in the area of Rockfield in the Black Snake River but scattered now as far south as Star Lake, and beyond. In Suttis’s immediate family there were five sons and of these sons Suttis was the youngest and the most bad-luck-prone of the generally luckless Coldham family as Suttis was the one for whom Amos Coldham the father had the least hope. As if there hadn’t been enough brains left for poor Suttis, by the time Suttis came along.

Saying with a sour look in his face—Like you’re shake-shake-shaking brains out of some damn bottle—like a ketchup bottle—and by the time it came to Suttis’s turn there just ain’t enough brains left in the bottle.

Saying—Wallop the fuckin’ bottle with your hand won’t do no fuckin’ good—the brains is all used up.

So it would be told that the solitary trapper who rescued Mudgirl from her imminent death in the mudflats beside the Black Snake River had but the mind of a child of eleven or twelve and nowhere near the mind of an adult man of twenty-nine which was Suttis’s age on this April morning in 1965.

So it would be told, where another trapper would have ignored the shrieking of the King of the Crows or worse yet taken shots with a .22 rifle to bring down the King of the Crows, Suttis Coldham knew at once that he was being summoned by the King of the Crows for some special purpose.

For several times in his life it had happened to Suttis when Suttis was alone and apart from the scrutiny of others that creatures singled him out to address him.

The first—a screech owl out behind the back pasture when Suttis had been a young boy. Spoke his name SSSuttisss all hissing syllables so the soft hairs on his neck stood on end and staring up—upward—up to the very top of the ruin of a dead oak trunk where the owl was perched utterly motionless except for its feathers rippling in the wind and its eyes glaring like gasoline flame seeing how the owl knew him—a spindly-limbed boy twenty feet below gaping and grimacing and struck dumb hearing SSSuttisss and seeing that look in the owl’s eyes of such significance, it could not have been named except the knowledge was imparted—You are Suttis, and you are known.

Not until years later came another creature to address Suttis and this a deer—a doe—while Suttis was hunting with his father and brothers and Suttis was left behind stumbling and uncertain and out of nowhere amid the pine woods there appeared the doe about fifty feet away—a doe with two just-born fawns—pausing to stare at Suttis wide-eyed not in fright but with a sort of surprised recognition even as Suttis lifted his rifle to fire with a rapidly beating heart and a very dry mouth—Suttis! SuttisSuttisSuttis!—words sounding inside his own head like a radio switched on so Suttis was given to know that it was the doe’s thoughts sent to him in some way like vibrations in water and he’d understood that he was not to fire his rifle, and he did not fire his rifle.

And most recent in January 1965 making early-morning rounds of the traps, God damn Suttis’s brothers sending Suttis out on a morning when none of them would have gone outdoors to freeze his ass but there’s Suttis stumbling in thigh-high snow, shuddering in fuckin’ freezing wind and half the traps covered in snow and inaccessible and finally he’d located one—one!—a mile or more from home—not what he’d expected in this frozen-over wet-land place which was muskrat or beaver or maybe raccoon but instead it was a bobcat—a thin whistle through the gap in Suttis’s front teeth for Suttis had not ever trapped a bobcat before in his life for bobcats are too elusive—too cunning—but here a captive young one looked to be a six-to-eight-months-old kitten its left rear leg caught in a long spring trap panicked and panting licking at the wet-blooded trapped leg with frantic motions of its pink tongue and pausing now to stare up at Suttis in a look both pleading and reproachful, accusatory—it was a female cat, Suttis seemed to know—beautiful tawny eyes with black vertical slits fixed upon Suttis Coldham who was marveling he’d never seen such a creature in his life, silver-tipped fur, stripes and spots in the fur of the hue of burnished mahogany, tufted ears, long tremulous whiskers, and those tawny eyes fixed upon him as Suttis stood crouched a few feet away hearing in the bobcat’s quick-panting breath what sounded like Suttis! Suttis don’t you know who I am and drawn closer risking the bobcat’s talon-claws and astonished now seeing that these were the eyes of his Coldham grandmother who’d died at Christmas in her eighty-ninth year but now the grandmother was a young girl as Suttis had never known her and somehow—Suttis could have no idea how—gazing at him out of the bobcat’s eyes and even as the bobcat’s teeth were bared in a panicked snarl clearly Suttis was made to hear his girl-grandmother’s chiding voice Suttis! O Suttis you know who I am—you know you do!