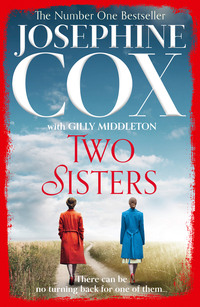

Two Sisters

‘Morning, Dora … Nell.’

‘Morning, Tom.’

‘Morning, Mr Arnold.’ Ellen beamed at remembering to be formal, even though all those present were family. She was learning already that appearances were important at the Hall.

‘You ready to get started, Nell? You could take over here, clearing up these dropped blooms and generally tidying the drive while I go and see to the lawn mower. Be sure to get up all these brown flower heads, pull out any weeds from the gravel and then just rake it over lightly.’

‘Of course, Mr Arnold,’ Ellen smiled willingly. She took off her old Fair Isle cardigan and hung it over the handles of the wheelbarrow. Her gardening gloves were in her bag – her school satchel, which was proving useful years after she’d left school – because she’d proudly taken them home to show her parents. In the end, only Dora had admired them.

‘Thank you, Nell. I’ll come and see how you’re getting on in a bit.’

He and Dora moved on towards the house.

‘You all right, love?’ asked Tom when they were out of Ellen’s hearing. ‘Only you’re looking a bit tired, like.’

‘Aye, I am a bit weary,’ said Dora. ‘I’ll be all right once I get polishing.’

Tom smiled. ‘Have you time to tell me about it while I see to the lawn mower?’

‘Five minutes then, but we’ll stay outside. I don’t want anyone getting the wrong idea: you and me in the shed together.’

Tom threw back his head and laughed. ‘Aye, lass, that would never do.’

They walked round to what Ellen had thought yesterday looked like a little village of garden outbuildings and Tom opened the big shed and wheeled out the lawn mower. Then he and Dora sat down behind it on a couple of large upturned plant pots, where they could see anyone approaching.

‘What’s the matter? Is it that brother of mine?’

‘Well, I can hardly blame him for worrying,’ said Dora, loyally. She told Tom the sorry tale of the dead sheep and lambs.

‘So he was fretting and worriting all night? I can imagine. Not a thought that you might need a good night’s sleep before another day’s work. Selfish bugger. Typical: if he’s got summat on his mind he makes sure everyone else shares the worry.’

This seemed to Dora a fair summary of Philip’s attitude throughout their marriage, and he was getting worse as he grew older. She was too tired to find any loyal words to contradict Tom. Suddenly tears sprang to her eyes and she brushed them away hastily before he saw and misunderstood.

‘Hey, chin up, lass,’ he said. ‘I’d be willing to bet there’s no more dead sheep today and the whole business will remain a mystery until everyone forgets about it.’

‘Aye, I’m hoping so.’

‘And Phil’ll go on about it for a few days, just to eke out the bad news, like, and then even he will have to shut up.’

Dora gave a watery smile. This also was a pretty accurate account of the pattern of Phil’s gloomy moods.

‘You never know, he might even remember he has two beautiful daughters – in addition to his remarkably fine wife – and be glad for them about their new jobs. It’ll do him no harm to think of summat beyond himself.’

‘You’re right, of course, Tom, though I know there is cause to be anxious about the sheep, with everyone fearing foot and mouth these days. Phil takes his work at the farm very seriously – of course he does – but if it wasn’t the flock it’d be summat else causing him fretting or fury, and often it’s a trifling matter. It’s hard work bearing the weight of all his pessimism, and the girls shouldn’t have their home life cast under a black cloud and be tiptoeing round their father’s ill temper all the time. I worry they’ll be off at the first opportunity – and I could hardly blame them – and then it’ll just be me trying to cope with Phil alone. I don’t know if I’d be able to manage. Sometimes it’s like he’s sucking all the joy out of my life.’

Tom reached out and took Dora’s hand where it rested in her lap, and she didn’t resist when he raised it to his lips and gently kissed the back of it.

‘Oh, Dora,’ he murmured, ‘if only—’

‘—it had been different,’ she finished. ‘But it is what it is, lad, and I’d best get on and tackle that sitting room before Mr and Mrs S want to be in there.’ Reluctantly she pulled her hand away, stood up, brushed off the seat of her thin coat and straightened her shoulders. She never allowed herself more than a minute or two alone with Tom, yet she relished that brief time as a thirsty insect might devour tiny drops of water on a petal. She must never look for more than that, she knew; she could not trust herself.

‘And I’d best oil this beast and make the first cut of the season,’ said Tom, also getting to his feet but not taking his eyes off Dora.

‘How did Nell do yesterday?’ she asked, stepping away and adopting the tone of Mrs Arnold, the Hall’s reliable domestic. ‘She seemed to think it went all right.’

‘It’s early days but I think she’ll be grand,’ said Tom Arnold, the gardener. ‘Oh, but, lass, we need to be extra careful with both the girls here,’ he added quietly.

‘Huh, Gina! I don’t know what she’s playing at, but I’ve had a word about the kind of behaviour I expect – or rather, don’t expect. I don’t want her giving the Arnolds a bad name. We have our reputations to think of,’ said Dora pointedly, then smiled and turned for the house.

‘As if I’m not thinking of your reputation every day,’ Tom murmured, watching her go. ‘Why else would I be feeling this way about you and doing nowt about it?’

Gina pedalled down the drive of Grindle Hall. Ahead she could see her sister bending over a pile of dead flower heads she had raked together.

‘Morning again, Nell,’ Gina called as she passed, and managed, with a well-timed kick, to tip the wheelbarrow onto its side, spilling the soggy brown debris of spent flowers onto Nell and the gravel, and casting her cardigan and satchel onto the ground. ‘Whoops, sorry!’ Gina called as she rode on, not looking back.

She continued round behind the kitchen and left the bicycle in one of the outbuildings. Then she went into the house via the kitchen door. Even Gina knew it wasn’t her place to use the front door when she arrived, though already she dreamed of a time when it would be. As she’d said to Ellen, you have to dream big dreams if you want to get on in life. And now she had this strange, new and rather frightening power that she didn’t yet understand. It couldn’t just be a coincidence that the sheep had died, could it? Gina questioned herself once again and came to the same disturbing conclusion: she had killed the sheep by mistake. No one need ever suspect, so her secret was safe. She had already resolved to be more careful in future.

Mrs Bassett was at the kitchen table, rolling out pastry.

‘Good morning, Mrs Bassett,’ said Gina.

The cook looked up. ‘Good morning, Ellen Arnold. Would you get me some taters, please, and I think there’s a bit of salad ready under those cloches. Mr Arnold will show you.’

‘Oh, I’m not Ellen,’ said Gina, laughing, but politely. ‘I’m Georgina.’

Mrs Bassett looked puzzled. ‘But I thought your name was Ellen. Aren’t you working in the garden with Tom Arnold?’

‘Oh, no. The garden’s nowt to do with me, Mrs Bassett. I’m working for Mrs Stellion,’ said Gina, and went through the door into the corridor, then up the stairs to the green door and on into the hall, amused at leaving the poor woman plainly confused.

She quickly collected Coco’s lead from the boot room and then went to find Mrs Stellion and her puppy in the morning room, where she’d met the lady the previous day.

See, only one day in, and already you’re going about your business in the house quite happily.

When she thought of the previous day and how Nell and Uncle Tom had come bowing and scraping up the back stairs, she almost laughed aloud.

She knocked on the closed door, heard the call to enter, and in an instant the little dog was yapping and panting around her feet. He was a bonny young fella and it would be easy to become fond of him, she decided, and if she meant to make herself indispensable, Coco could be a real asset. She bent to greet him with almost equal enthusiasm.

‘Gina, good morning,’ said Mrs Stellion. ‘How prompt you are for Coco’s walk. I do like people who are reliable. You’ve even got his lead handy. Now, if you walk him around the garden for twenty minutes, clean his feet, then back up here for biscuits, that will be fine.’

‘Yes, Mrs Stellion,’ said Gina, hoping there would indeed be biscuits, though she suspected Mrs Stellion meant for the dog.

She fastened the lead on the puppy’s collar and walked him down to the hall, then slipped out through the front door and down the steps to the gravel. This was, after all, Coco’s home, even if it wasn’t hers.

She led him round the house to the back, meandering in and out of the different parts of the garden, opening doors and gates to see what was what, memorising which areas were most suitable for the dog and which were of more interest to herself. When they got to the back they played a while on the grass with a stick Gina had found.

Soon Tom appeared wheeling a gigantic green lawn mower.

‘Hello, Uncle Tom,’ Gina called.

‘All right, lass? Looks like that dog needs a ball to play with.’

‘You’re right. I don’t know if he’s got one. I’ll have to ask Mrs Stellion.’ She laughed at the idea of Mrs Stellion running about on the grass throwing a ball for the energetic puppy. Of course, that was the very reason she was here.

Tom bent to fondle the puppy’s ears and he barked delightedly, loving the attention. ‘Nice little dog,’ Tom said. ‘I may know where there’s summat he can play with. Come and find me later.’

‘Thank you, Uncle Tom,’ said Gina, and scampered after Coco, who was now heading for the flowerbed. ‘Coco, come here, you little beggar …’

Tom watched her go. In some ways she resembled the carefree and undisciplined puppy, he thought. Gina was all right, but not steady like Nell. He had to admire the way she’d got herself this dog-walking job, though. However she’d managed it, it had been fast work. He made a mental note not to underestimate his niece Gina.

Edith Stellion looked out of the morning-room window at Coco playing with the stick the Arnold girl had found for him. Her husband, George, came to stand beside her and they watched together in silence. George glanced at his wife and saw that she was smiling at the antics of her little dog running around with the new girl – what was her name? Not Ellen … Gina? – but at the same time there was sadness in her eyes. He knew what she was thinking.

‘She’d have been about that age now, wouldn’t she?’ he said. ‘Clarissa.’

Edith nodded. ‘Seventeen next week.’

‘Of course.’

They stood quietly watching for a few more minutes.

‘Looks like Coco is going to be a handful, Edith,’ said George. ‘Are you sure such a lively puppy was a good idea?’

‘No,’ laughed Edith, throwing off her sadness at the thought of their little daughter who had died long ago, ‘but he’s very sweet-natured and amusing, and if Gina Arnold is taking him out most days, then I think he’ll not be too boisterous for me.’

‘Hmm …’

‘She can help me with his obedience training. And it’s nice to have a young face about the place, don’t you think?’

‘I agree. I know it’s a bit quiet for you when I’m out on business, and with Diana and James away now most of the time, though I admit to being confused which of the Arnold girls is which. Suddenly there’s two of them here, and at first glance they do look surprisingly alike.’

‘They do indeed, though I think we’ll all soon learn. Mrs Thwaite says Mrs Bassett was all at sea about them earlier.’ They exchanged amused glances.

‘Mrs Bassett is a dear, and a wonderful cook,’ said George, then lowered his voice, ‘but not especially clever in other regards.’

Edith was thinking. ‘George, I know it’s early days, but if Gina Arnold works out well with Coco, you wouldn’t mind if I gave her a few other little tasks to do for me, would you?’

‘No, darling, if you think she’s the right person. What have you in mind?’

‘Oh, just keeping me company, really. It’s a big effort to go out if I’ve got one of my headaches or I’m in a sad mood.’ She sighed. ‘I can hardly ask Mrs Thwaite, can I?’

‘Of course not.’ George thought of the elderly and humourless housekeeper. She had been at the Hall for several years and, really, with Diana and James in London much of the time, there was little for her to do most weeks. She was only kept on out of kindness because she was a widow, but Edith had never been especially fond of the prickly woman. ‘But Gina Arnold – I’m assuming she’s a village girl through and through, if she’s anything like her sister. Though of course their mother is Dora, and she has her own dignity, for all she’s had very few advantages, nor, I imagine, lived anywhere but Little Grindle. But do you really think Gina Arnold would be the kind of young woman to amuse you when you’re feeling low?’

‘Ah,’ said Edith. ‘There you have me. But I think I might find out as time goes on. I suspect that a lively, reliable and good-natured girl about the place will probably do me no end of good.’

Ellen had had a trying day. After Gina had knocked over the barrow, she’d had to shovel up all the dead flowers and the weeds again, and then there’d been a sudden shower of rain while she was tying up some roses and she’d got uncomfortably wet. Now, this afternoon, Gina was queening about on the lawn, playing with the puppy while she, Ellen, was standing on a plank in the damp herbaceous border next to it, weeding with a long hoe.

Coco came snuffling round to see what she was doing and, instead of calling him away, Gina encouraged him to make a nuisance of himself.

‘Can’t you just go away while I’m working here?’ Ellen said eventually.

‘Are you talking to me or the dog?’ Gina asked innocently.

‘Well, the blessed dog, obviously,’ Ellen snapped. ‘I wouldn’t expect an intelligent reply from you.’

‘No need to adopt a tone,’ said Gina. ‘I’m just doing my job, same as you.’

‘Job! What kind of a job is it, for goodness’ sake, gallivanting around with a puppy?’

‘Same as yours. You answer to Uncle Tom and I answer to Mrs Stellion, so I reckon that makes it a proper job, Nell, so you can get down off your high horse.’

Ellen bit back her retort and took a deep breath. Surely Gina and the dog wouldn’t be out here for long. She’d just ignore them. But it proved hard to ignore a mischievous and playful puppy when he started chewing the gloves Ellen had taken off and left on the newly cut grass because her hands were hot. Gina just stood watching and giggling.

‘Just go, can’t you, Gina? Why do you have to play here?’

‘All right, we’re going. No need to get all worked up. We’ve enough of that at home with Dad,’ she said. ‘Come on, Coco …’ She fastened his lead back on his collar. ‘We’ve got the rest of the garden to play in, haven’t we, boy? Let’s go and see how those strawberries are getting on.’

‘Don’t you dare let Coco go among those strawberry plants,’ said Ellen. ‘He’ll only wee on them and ruin them.’

‘I was only joking, Nell. You should see your face, though,’ said Gina, and, laughing loudly, led the puppy away.

‘How did you get on?’ asked Tom when Ellen had finished a good area of the border and come back to the sheds for a cup of tea.

‘All right, I suppose. I’ve done about a third, but I could have managed better without Gina and that dog messing about round me.’ Ellen wasn’t a habitual taleteller but she didn’t want to have to put up with Gina and Coco every morning and afternoon. Gina had a cruel streak and knew instinctively how to wind people up.

‘I’ll have a word,’ said Tom.

Ellen hoped that would be the end of the matter. Both girls liked and respected Uncle Tom, and even Gina would do as he asked. But Ellen felt uneasy about having Gina around at the Hall, as if Gina had somehow pushed into her life, which was unfair when she considered that both had started working there on the same day. Maybe it was the suddenness of Gina coming here that was unsettling. Ellen had to admit that she hadn’t felt quite at ease since Gina had slapped her hand away from that little bottle hidden in the wall and then started talking some rubbish about witches’ spells. It was hard to forget about that and the mad look she’d seen on Gina’s face. Despite what Gina had said the previous night, she couldn’t really believe she’d heard the last of it.

CHAPTER FOUR

‘NELL, YOU’VE GOT a visitor,’ Tom announced.

Ellen looked up from pricking out seedlings on the greenhouse bench. It was hot behind the glass in late May; she had her sleeves rolled up and was feeling rather clammy.

‘Ed! What a nice surprise.’ She brushed a strand of hair away from her flushed face with her forearm. ‘We haven’t seen you at the cottage for a week or two. Is everything all right?’ She put down her dibber and wiped the soil off her hands on an old towel.

‘I won’t keep you long, Nell; just wanted to say hello as I was here anyway.’ Edward Beveridge turned to Tom. ‘If that’s all right …?’

Edward felt slightly overheated himself. For one silly moment he didn’t know whether to remove his cap on entering the greenhouse. He’d thought to look Ellen out when he came up to the Hall to deliver some meat that Mrs Thwaite had ordered. Now, seeing Ellen working in this imposing place, setting what looked like hundreds of tiny plants, he realised he knew nothing of her life since she’d left the farm nearly two weeks ago and he felt overawed. With her eager face and untidy hair, she looked very young and very pretty, an attractive combination with the confidence and self-possession she was displaying in her new work.

‘Nell knows what she has to get done,’ said Tom, smiling.

‘Thank you, Mr Arnold.’

Tom went off to tend the vegetable plot and Ed turned to answer Ellen. ‘Aye, thank you, we’re all fine. Mum says you’re to drop in any time.’

‘I’ll do that. It’d be lovely to see her. I was right glad to hear no more of the sheep died. It must have been a terrible worry for you.’

‘It was, but that’s behind us now.’

They stood awkwardly for a moment, Ellen keen to get on but not wanting to seem rude to her friend, Edward reading that thought in her face and beginning to wish he’d gone straight home. He must think of something to say, and quickly.

‘Would you like—’

‘Well, I really must—’

They both spoke at once.

‘Please, you first,’ said Ellen.

‘I’m just wondering if you’d like to come for a walk up the field this evening – after you’ve finished work, of course. Mum could pack up a tea for us.’

‘Thank you, I’d love to,’ said Ellen. ‘It’d be nice to catch up on everyone’s news. I’ve been so busy since I started here.’

Edward took the hint. ‘Come over whenever you’re ready, then.’

‘I’ll look forward to it.’ Smiling, Ellen picked up her dibber to resume her task while Edward turned to leave, grinning.

At midday Tom reappeared and told Ellen it was time to stop working.

‘Oh, the time just flies by when I’m busy,’ she said. ‘I didn’t realise it was so late.’

‘Well, it’s library day,’ Tom reminded her, ‘so we’d best get a move on if we don’t want to be fined next time for late returns.’

‘I hadn’t forgotten,’ said Ellen, and went to the shed to collect the books she’d brought with her.

Tom and Ellen walked down the drive to the main gate together, meeting Mrs Thwaite coming the other way carrying a small pile of books, and found the van parked neatly up against Tom’s cottage. Tom nipped inside to fetch his books while Ellen mounted the steps and presented hers, opening them at the pages with the date stamps and the little cardboard pockets.

The usual librarian, Mr Shepherd, wasn’t there today. Instead there was a younger man with round wire-rimmed glasses and a severe haircut, which could not disguise that he was very good-looking.

‘Mr Shepherd not well?’ asked Ellen. She’d grown fond of the kindly librarian with his gentle manner and knowledgeable reading recommendations, even about light fiction.

‘Mr Shepherd’s been assigned to the archives,’ said the new man.

‘Oh …’ Ellen was worried. Was that a discreet way of saying he’d been forced into retirement? He was getting on in years but he hadn’t said anything about retiring when he last came by. ‘And does he … is he quite happy about that?’

‘I wouldn’t know,’ said the man abruptly. ‘Why do you ask?’

Goodness, what a rude man! ‘Well, it’s only … well, Mr Shepherd’s been the librarian for a long time and … folk are fond of him.’

‘Aye, in Little Grindle we care about folk,’ said Tom, coming in with his books. ‘We’re like that round here.’ He gave the new man a stern look but it didn’t soften his manner.

‘Indeed?’ he said dismissively. Then barked at Ellen: ‘Name?’

He took the tickets under her name from his card index box, placed them in the books and then closed the volumes to put on the ‘Returned’ shelf, glancing at the titles.

‘Romances down at the end,’ he said with a slight sneer, pointing.

Ellen shuffled away, feeling as if her taste were being judged and found wanting.

As she was returning with her chosen books, she noticed there was a shelf of practical kinds of books: handicrafts, woodworking and gardening. She hadn’t thought to look there before, never venturing beyond light romances, which she and Dora both read in the fortnight they were lent out. There was a picture book of beautiful gardens and she wondered if it was worth a look, if only to compare the photographs – which were, disappointingly, mainly in black and white – with Grindle Hall, so she took that to the librarian’s little desk too.

‘The rule is you’re allowed only three volumes,’ said the new librarian.

Ellen knew this and felt foolish for forgetting to put one of the novels back when she’d found the gardens book. She was starting to apologise when Tom interrupted, approaching with a couple of hefty novels from the classics section.

‘I’ll put one of yours on my ticket,’ he said.

‘No borrowing is allowed on another reader’s ticket,’ said the librarian, not looking up from his card index.

‘I’m not borrowing on Miss Arnold’s ticket,’ said Tom mildly. ‘I’m borrowing on my own ticket.’

‘It’s all right, Uncle Tom, I’ve decided not to have this book after all,’ said Ellen, and put one of the novels to one side. ‘I’ll take the gardens book instead.’

‘It would be helpful if you didn’t take books from the shelves that you don’t wish to borrow,’ said the librarian, snatching up the novel and putting it on the ‘Returned’ shelf.

‘But I want to borrow it,’ said Tom, taking it carefully off the shelf and adding it to his pile of books.

The librarian stared at Tom for a long time with raised eyebrows. Tom returned the look and the librarian blinked first.

‘See you next time,’ Tom said in a friendly tone as he and Ellen descended the steps, clutching their stamped books.

Ellen couldn’t help bursting out laughing, although she suspected the librarian could hear her.

‘Oh, Uncle Tom, you are brilliant,’ she giggled. ‘Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens and The Fickle Heart of Lady Blanche.’

‘I shall enjoy that one no end,’ said Tom, deadpan, handing it over to Ellen. ‘Whoever Lady Blanche is. Make sure you bring it back next time, love. I don’t want my wrists slapped by that jumped-up little stand-in for our Mr Shepherd.’