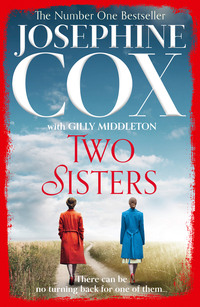

Two Sisters

‘I wonder what’s happened to Mr Shepherd. He’d surely have told us if he was expecting not to be round in the van any more. That rude man said he’d been “assigned to the archives”, but I don’t really know what that means.’

‘Oh dear, I wonder if that’s a euphemism for being pensioned off. I’ll make some enquiries …’

Gina enjoyed going up to the Hall twice a day. She didn’t mind exercising Mrs Stellion’s puppy, but being at the Hall was, to her, the whole point of her employment. She always eked out the tasks of cleaning Coco’s paws and tidying away his lead and the old tennis ball Tom had found for him so that she could spend as long as possible around the house.

This morning Mrs Stellion was in good spirits and was sitting writing letters with a fountain pen, quickly covering thick sheets of paper from her desk stand in neat writing, so that when Gina returned the happy dog to his owner, Mrs Stellion was too occupied to chat for long. Nor was there tea and biscuits laid out on a tray for Gina and her employer, as there sometimes was.

‘Oh, thank you, Gina,’ said Mrs Stellion, looking up and smiling at the dog. ‘Good boy, Coco. Sit!’

Coco obediently sat down beside his mistress’s chair at her leather-topped desk, a vase of fragrant early roses on it.

Gina felt proud of her pupil. ‘He’s coming on well, isn’t he, ma’am?’ she said, looking for praise.

‘Indeed. He’s a clever young fellow. Coco and I will see you this afternoon, then, thank you, Gina.’

‘Yes, Mrs Stellion. Goodbye for now.’ Gina knew she was being dismissed.

It was a beautiful morning and she didn’t fancy cycling home to do household chores until it was time to return here. Maybe she could just stay if she didn’t get in anyone’s way.

She went back to the gloomy entrance hall but, instead of leaving through the green door at the back, she decided to do a little exploration. Gina had seen Mr Stellion driving away in the big car earlier, so she knew only the morning room was occupied. She also knew that Dora was cleaning upstairs today and Mrs Thwaite was doing something in the kitchen. It was a good time to have a little look around.

Gina took the other corridor from the hall. There were four doors off it, mirroring the arrangement of rooms at the far side, and she opened the first slowly and peered in. It was filled with bookcases and the window blind was pulled down to keep the light low. She moved on.

She saw light was pouring in at the far end. The door on that side must be glass. Of course … it was a conservatory; she’d seen it from the outside. She approached, glanced quickly behind her to see that the coast was clear, then crept in and closed the door quietly.

It was quite a big room, with a high glass roof and stone floor, which was damp in places, as if the many plants in pots had recently been watered. It was very warm and the air smelled green and lush. Gina sat down in one of the basket-like chairs set between the pot plants, arranged the cushions and closed her eyes …

‘And what do you think you’re doing, young woman?’ asked a severe voice.

Gina opened her eyes and saw Mrs Thwaite standing in front of her.

‘Oh, Mrs Thwaite, I’m afraid I got lost and then it’s so warm in here that I—’

‘Lost? Really? You didn’t look like you were making much of an effort to find your way out,’ said Mrs Thwaite.

‘No. As I said—’

‘I heard enough of what you said, Gina Arnold. You may have business here playing with Mrs Stellion’s puppy, but let me remind you, that is all the business you have here.’

‘I was only—’

‘I can see exactly what you “were only” doing. I hope I don’t need to remind you that you are not a resident of this house. Your job – if “job” it can be called – is to entertain the dog, make sure he’s clean enough to be inside on the furniture and then to leave.’

Gina felt herself turning pink with fury. Entertain the dog! That made her sound as if she were the dog’s servant. Mrs Thwaite had clearly plucked up the courage to take some pathetic revenge for what Gina had said to her on that first morning. Most days they managed to avoid each other – and certainly that suited Gina, who would rather the episode about the missing money at the village shop were well and truly forgotten – but Gina knew she had overstepped the mark by being here today. Simmering with anger though she was, she bit back the insult she was about to fling at Mrs Thwaite and decided to retreat with what dignity she could.

‘Yes, Mrs Thwaite,’ she said quietly. ‘It’s all right, I’m leaving now.’ She went to the door, but the housekeeper was there before her and opened it, so that Gina knew she was literally being shown out, as if she wasn’t to be trusted. She walked back up the corridor and Mrs Thwaite followed behind her like a gaoler escorting a prisoner. In the hall, Gina forgot herself for a moment and stepped towards the front door, as she did when she walked Coco.

‘Back stairs,’ barked Mrs Thwaite, pointing the way. Then, as Gina passed in front of her to reach the green door, she hissed, ‘And don’t you ever forget your place in future, Gina Arnold.’

Gina didn’t answer or look back, but went through the door, glad of the cooler air on the staircase against her burning face. She went down the corridor, past the kitchen and to the door at the end, which opened into the courtyard where the outbuildings were. She wheeled out the bicycle and pedalled away, not looking round, knowing she’d been well and truly bested by the housekeeper this time.

Mrs Stellion was usually very friendly – less so today because she was busy – but now Gina felt as if she’d had a wake-up call. She had thought she had a way into the lives of those at the Hall, only to have it brought home to her that she was merely the girl who walked the dog – the dog’s servant, as Mrs Thwaite had implied. Dora had the run of the house and was trusted, after many years of service, and Ellen was learning a proper trade and, from what Gina had seen of her in the garden, was going about it in a very competent manner. But she … oh, it was too bad: sacked by Mrs Beveridge and now practically thrown out of the Hall by the housekeeper. For a moment she wondered if she would bother going back this afternoon, but it was Mrs Stellion she answered to, and it was possible that the lady neither knew nor cared that her dog walker had sat down in her conservatory. Gina decided it would be worth returning to see how the land lay.

In the meantime she had a few hours alone at the cottage until it was time for Coco’s afternoon walk. She had avoided taking the little book of spells out from its hiding place since the incident with the sheep. Events had run away with her then, and she had felt unsettled by the suspicion that the power she could muster was not entirely under her control. Now, though, passing time had blunted her fear, and she decided she needed a little help if she were to teach Mrs Thwaite the lesson she deserved. She arrived at the cottage, unlocked the door and rushed upstairs to consult her book.

‘Good grief, Gina. What on earth is that awful smell?’ asked Ellen. ‘It’s like a singed perm, but it doesn’t look as if you’ve burned your hair,’ she said, staring at Gina’s long brown curls, which looked just the same as usual.

‘It must be bleach,’ said Gina, thinking fast. ‘I got a mark on my shirt and I’ve been trying to get it off.’

‘Mm …’ Ellen opened the window of their room to let in some fresh air. ‘I’m off out with Ed in a minute, when I’ve got changed. We’re just going for a walk and a packed tea. Do you want to come?’

‘No fear,’ said Gina. ‘I’m not playing gooseberry to you two.’

‘Don’t be daft.’ Ellen changed out of her shirt and breeches and put on a cotton frock, first time on this year. It looked shorter and was definitely tighter than it had been on its last outing, and somehow the fabric had faded on top of the skirt gathers since she’d put it away in September. Strange how clothes changed when you didn’t wear them for a while. Sometimes they came out looking better; mostly they were worse.

‘What do you think of this? Does it look too tight?’

‘A bit,’ said Gina.

‘Ah, well, it’ll have to do. I’ve nowt else and I only wanted summat cool to wear. It’s been hot today, potting up seedlings. How did you get on “popping over to the Hall to exercise Coco”?’

Gina rolled her eyes; the joke had lost its sting with frequent repetition. Instead of answering she asked, ‘What do you think about Mrs Thwaite?’

‘I don’t have owt to do with her really. She’s all right whenever I do see her, though. Why?’

‘Nowt … Just wondered.’

‘I know she takes her books to the mobile library, same as me and Uncle Tom. We met her on her way back. Mr Shepherd – you know, the old librarian who’s always so friendly – he wasn’t there. He’s always been there before now. Funny that Mrs Thwaite didn’t mention it when we met her.’

‘Mebbe she doesn’t get on with Mr Shepherd.’

‘No, Mr Shepherd gets on with everyone. Uncle Tom’s going to try to find out what’s happened. What if he’s ill? Folk in Little Grindle would want to do what they could for him.’

‘Nell, I’ve really no idea,’ said Gina.

Ellen took her brush through her hair and tied it back with her home-made blue scarf knotted in a bow above her ear. ‘Right, I’m off to the farm. See you later.’

Gina listened to her sister’s feet descending the stairs, then Ellen was saying something Gina couldn’t hear to Dora, and then there was the sound of the back door closing.

She pulled the shabby little volume of spells out from under her bed, with a candle, a box of matches and a saucer, a bottle of vinegar, various bits of plants she hoped she’d identified correctly, and some scraps of paper on which she’d written various wishes for the intervention of whatever power she’d hoped to conjure up before she’d gone to walk Coco that afternoon. Whether it had worked or not, she didn’t know. Mrs Stellion hadn’t mentioned the conservatory and Gina had seen nothing of Mrs Thwaite. So far as Gina was concerned, that was a good result to be going on with. Time would reveal whether the short-tempered housekeeper had met her match.

Ellen and Ed took the well-worn path past the hen houses, up through the gate into the field where the girls had lazed on their afternoon off, and on up higher. Ellen remembered about the silly business with the little bottle, but whatever Gina had been up to, nothing had come of it and Ellen’s fear of that mad moment had faded until it was almost forgotten.

‘Such a lovely hot day,’ she said. ‘Like midsummer. The air’s a bit fresher up here, though.’

‘Aye, it is, but look over there.’ Edward pointed to the west. ‘Those clouds mean rain, though I think we’ll be all right for this evening.’

‘Shall we stop here for our tea?’ asked Ellen after a few more minutes. ‘The view’s amazing this high up.’

Edward laughed. ‘Yes, a rare sight to be able to see so far. Look, there’s the Hall over there, and the village street stretching away. Half the year the clouds are down to the ground and all you can see up here through the fog is tragic-looking sheep clinging onto the fell.’

‘Don’t I know it! I was helping with them until a few weeks ago, don’t forget.’

‘It feels as if you’ve been gone for ages,’ said Edward, sitting on the dry cropped grass.

‘Yes, funny, that. I feel the same,’ smiled Ellen.

‘Do you miss it?’

‘Oh, no, not at all. It was nice working with you and your parents, but I think I like gardening better than farm work,’ said Ellen. ‘And I’m learning all kinds of new things. You can understand why I’m keen on that, can’t you, Ed?’ She was anxious not to offend by mistake.

‘Of course.’

‘I want to learn all about gardening, get to know everything Uncle Tom knows – and he knows so much I think it will take me years to catch up – so that one day mebbe I can be in charge of a garden. I’d like to learn to cut those bushes into shapes like chessmen, though I’d settle for trimming a box hedge straight for now,’ she laughed. ‘You don’t think it’s daft, do you, that I should want to learn and mebbe even be a head gardener somewhere?’

‘’Course not. Why would it be daft?’

‘Well, I’m just Ellen Arnold, who lives in a tied cottage in Little Grindle and hasn’t much of an education. It’s not like I live in a place where there’s lots of different things happening and opportunities to do them.’

‘You never know, you might still get to do all sorts,’ said Edward. ‘If you work hard enough, I reckon you can do whatever you want. It’s not about where you come from, is it, Nell? It’s about where you’re going: all the things you’re going to do in your life. When I saw you this morning you looked as if you knew exactly what you were doing with all those little plants. That’s a start, isn’t it?’

‘Thank you, Ed. There’s so much to learn that I sometimes feel as if I’ll never get anywhere with it. I am trying hard, though.’

‘I know you are. And think how much you’ve done in the time you’ve been at the Hall. I reckon Mr Arnold wouldn’t be putting up with anyone who was a hindrance and not a help. He wants the best for the Hall garden, and he won’t waste time with you if you’re no good to him, even if you are his niece.’

‘True,’ Ellen conceded. ‘He’s kind, but I know he’d say if I were hopeless. And you’re kind, too, pulling up my spirits like that.’

‘Aye, well, just don’t be setting off down the road to success and forgetting who your friends are, will you?’ Edward said. ‘And I’d really miss you if you went away to be head gardener at some other big house. We all would – Mum and Dad as well as me,’ he added, shy about his feelings and safely diluting them by bringing his parents into it. ‘I’m a farmer’s only son so I shan’t be going anywhere. My future was mapped out at birth.’

‘Well, I’m here for now, and for at least the next ten years if I’m to learn everything about gardening from Uncle Tom,’ smiled Ellen. ‘Now, I’m starving and I expect you are, too. What’s your mum packed in that picnic basket? It’s heavy enough for a feast.’

‘I reckon she’s feeding us up,’ said Edward, pleased Ellen had no real plans to leave Little Grindle. He admired and understood her ambition, but he certainly didn’t want her to go away. He had, at the back of his mind, plans for his own life that might well include Nell Arnold.

CHAPTER FIVE

‘WE’RE ALL SET for summer, I see,’ said Philip, casting a disgruntled look through the kitchen window at the rain teeming down. ‘It’ll be like this for weeks now, you mark my words.’

‘You don’t know that, Dad,’ Ellen said. ‘It was that hot yesterday it felt like midsummer. Could be as quick to change again.’

‘I doubt it,’ said Gina, recklessly imitating her father’s voice and pulling a long face. ‘Cheer up, Dad, we might all be dead by July.’

‘Gina, shut up.’

‘Gina—’

‘You’re not too old to feel the back of my hand,’ threatened Philip as Ellen and Dora tried to shush her. They all knew that, Gina most of all. He took a step towards her with his arm raised and she stepped quickly out of reach, the smile gone from her face immediately.

‘Sorry, Dad,’ she muttered, then quickly said, ‘I think I’ll take Coco for a run around the outbuildings; save us both getting wet.’ She watched ribbons of rain cascading down the windows.

‘You’d better ask Mrs Stellion,’ Dora suggested to her. ‘She might want her dog to have a proper walk, rain or no rain.’

‘He won’t shrink in the wet, Gina,’ said Ellen.

‘No, but I might. Perhaps we’ll even play inside and not go out at all,’ Gina mused.

‘Well, I think it’s time you got yourself a proper job, like our Nell, and stopped “playing” with puppies,’ said Philip. ‘Just ’cos you got the sack from the farm doesn’t mean you can’t make a fresh start. After all, you got the sack from the shop but it didn’t stop you working again. You need to make the effort, Gina, if you even know what that means. Playing with puppies’ll get you nowhere in life.’

Like you’ve got somewhere, you mean? Gina intended to go an awful lot further in her life than the farm at the end of the lane. Her job at the village shop had been a short-lived disaster. Gina still maintained publicly that it wasn’t her fault the money in the till didn’t match the receipts.

‘You got the sack from the farm?’ asked Dora. ‘You never said.’ She, too, recalled the unpleasantness at the village shop. For a while she’d been reluctant to go there, which had been awkward, though the Fowlers were good people and hadn’t blamed her for the incident at all.

‘I hear they need someone for general labour at Fellside, that farm on the way to Great Grindle,’ Philip went on. ‘They grow vegetables and have a little dairy herd. Even you can muck out cows and pick taters, Gina. They needn’t know you were sacked if you don’t tell them – I know you’re good at keeping secrets; you have a good teacher – and you could work full time and earn your keep for once in your life. It’s time you started paying your way, and playing with puppies won’t be doing that.’

Ellen frowned, wondering what exactly he was referring to about secrets, but she knew better than to say anything, so instead she went to look out her wellingtons from under the stairs, keen not to get drawn into this kind of low-level argument that seemed to run perpetually between her father and sister, and which would occasionally erupt into physical violence.

‘General labour! Muck out cows and pick taters!’ Gina was horrified. She thought of Mrs Stellion’s pretty morning room and how she had the run of almost the entire garden to play with the dog. No way was she going back to filthy farm work! She had hardly begun to get her plans under way yet, but she meant to forget she’d ever seen a farm, never mind worked on one.

‘Why don’t you just get off to work,’ said Dora to her husband, keen to damp down the full-scale argument brewing between him and Gina, ‘before you get the sack, too?’

‘Aye, I’m going, woman,’ he said, and left, grumbling to himself as he buttoned up his coat.

‘What was he on about?’ Gina asked.

‘About you getting a proper job instead of “popping over to the Hall to exercise Coco”, as you know very well,’ said Ellen. ‘Still, at least you seem to be doing that all right. Just keep that dog out of the vegetables, though, and anywhere I’m working.’

‘What, outside? On a day like this? And I meant what did he mean about me being good at keeping secrets?’

‘I’ve really no idea,’ said Dora dismissively. ‘Now, Gina, tidy the kitchen before you leave for the Hall, please, and if you see Ellen working you’re not to disturb her.’

Dora and Ellen gathered their mackintoshes, hats, umbrellas and wellingtons, and went out, exclaiming at the fierceness of the downpour.

For a moment Gina stood staring out at the driving rain. It was tempting not to leave the cottage at all, but what Philip had said about going to work at Fellside Farm had unnerved her. She needed to make sure of her role at the Hall and there was no time to lose.

Dora shook out her wet coat and hung it on a hook in the downstairs corridor, then pulled off her wellingtons and put on the shoes she kept at the Hall. Not a good start to the day: rain running down the back of her neck, despite her rain hat and umbrella and, even more annoying, Phil in another of his black moods, and making snide remarks about her.

She would never forget his jealousy and suspicions about her so-called secret on the night Gina was born. She’d put up with it for years, although he’d never referred to it before in front of the girls. Dora hoped this was not the start of a season of blacker moods and worse temper in her difficult husband. Was that when their marriage started to go wrong, or had it been failing even before then? It was hard to remember a time when they were happy, before this darkness descended on Philip …

Dora held her newborn baby in her arms. She was a beauty, with fine dark hair and the softest skin on her perfect little body.

‘A lovely girl,’ said Betty Travers, the midwife. ‘All the right limbs in all the right places and a good weight, too. A wonderful start to the New Year: a baby born just on the stroke of midnight.’ She opened the bedroom window just a crack so that Dora could hear the church bells in Little Grindle ringing in 1939, then quickly closed it again. Betty didn’t believe in fresh air for her new mothers and babies, especially in January.

Dora smiled tiredly. It was wonderful to have a second daughter, a sister for Nellie to play with. Nell was little more than a baby herself, a clever little thing, walking and trying to speak, though she wouldn’t be two until the autumn. Dora had hoped for a daughter but kept this to herself because Philip had said he wanted a son. Well, he had a second lovely little girl and she just had to hope he’d come round to the news when he saw her.

Dora smoothed the baby’s damp hair. Oh!

‘Betty, she’s got a little mark just here … look. Is summat wrong? It won’t get bigger, will it? She won’t be scarred?’

Betty took the baby in her arms and looked closely. ‘Oh, bless you, Dora, it’s just a tiny birthmark. It might even fade as she gets older, but it certainly won’t get bigger. And she’s lucky it’s behind her ear: by the time this dark hair has grown it’ll be completely hidden. Don’t you fret, love, there’s nowt to be worriting over.’

Philip thought very differently, though, when he came in to see his new child.

‘What’s this, then?’ he asked, seeing the tiny birthmark straight away. ‘It looks like a little crescent moon, same as the one our Tom has on his arm.’

‘So it does,’ said Dora, feigning surprise. Of course, she had already thought this. ‘Mebbe it’s just summat that runs in families, like,’ she said, then realised this was leading her husband to entirely the wrong conclusions.

‘Well, I’ve got no birthmarks and I’m the child’s father,’ he growled. He looked pointedly at Dora. ‘Aren’t I?’

Dora caught Betty’s eye with a desperately tired look.

‘And Baby has your dark hair,’ the midwife joined in. ‘There’s a strong resemblance between your beautiful new daughter and yourself, I’d say, Philip.’ Betty and Dora had been good friends for years, but even Dora thought Betty was laying it on a bit thick with that.

‘But what about this mark?’ Philip persisted. ‘I’ve not got one, but Tom has.’

‘It really is of no account, Philip,’ Betty said. ‘Some babies have birthmarks and most don’t, and that’s all there is to it. Now, why don’t you go and make Dora a cup of tea? I’d say she was ready for one and I think I could manage one, too. We’ve been hard at work up here.’

‘Aye, I heard the fuss,’ Philip grumbled.

‘Well, you can be thankful you were out of it then,’ Betty replied shortly.

When Philip had retreated to the kitchen, Dora sighed deeply.

‘She’s a bonny little thing but my Phil does get some daft ideas,’ she muttered. Tears were now springing to her weary eyes. ‘After all that birthing, you’d think he’d be pleased to have his child delivered safe and sound. I wanted another little girl, though I didn’t say owt and I didn’t really mind. Little Nellie’s been such a good baby that I feel I know how to cope with girls. But as Phil wanted a boy, I reckon he’s disappointed.’