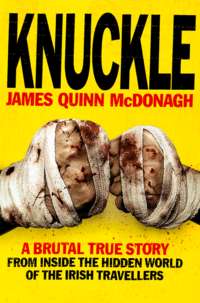

Knuckle

Everything we did in our spare time, we had to provide ourselves, whereas nowadays kids all have video games and things like that. We’d be out all day picking spuds from 6 a.m. until about four in the afternoon. Then straight away we’d have something to eat at home before running outside to play games: football, handball, kick the can – you name it. Even though we’d been working all day, we never felt too tired to play.

A couple of years later another change came that was even more exciting – we moved into a place in Mullingar, where I can remember my mother coming home from the hospital with my sister Maggie. It was a rough area, so bad that much of it has been demolished now, but we were there for a year or so before we moved south to Dublin, where we lived for a short while in Coolock, in the north-east of the city. We never stayed anywhere long enough for me to make friends or even to get to know anyone really.

Nineteen seventy-six was a blistering summer and we stayed right next to the beach for the entire summer. I spent the whole time outdoors, all day in that heat, swimming whenever we could. We had great times there. As well as my family, Chappy was there with all his kids, so we played every kind of game we could out on the beach. We stayed there right through till it was time to move on to start the potato-picking season in County Meath.

Family life was very good. My mother and father were very good to us; they were never too strict and always tried to give us whatever they could afford. They had no education, and so for us those early years were about survival. If my parents could afford a pair of Wellingtons or a pair of shoes or other clothing for us, they’d get them for us. Like every other travelling woman in Ireland in the 1970s, my mother went from door to door knocking for handouts and old clothes, and a lot of those clothes ended up on my back and on the backs of others in the family. That was true for 99 per cent of travelling families throughout Ireland in those years. But even though things were so bad, as a child I wasn’t aware of it. As long as we had food I didn’t mind how we lived.

From when I was 9 or 10 we were out doing a lot of farm work all over County Dublin, County Louth and County Westmeath. We’d pick potatoes, sprouts, sugar beet – anything the farmers had planted we’d be there to help harvest. I don’t remember liking the work but I certainly didn’t hate it. Working hard was something that we were just brought up to believe in doing, just as we believed God is God. Work wasn’t something that we had to be taught; we knew it almost from our very first breath. We believed that it had to be done, and everyone pitched in to make it easier for the family. For example, my mother didn’t just look after all of us, but worked too, selling things at a flea market, the Hill Market in Dublin, on a Saturday.

The time came when my father started thinking how much easier he’d found it to get work in England in the early 1960s. So he went back over to Manchester and when I was 10 we all followed him over. He had also told my mother about how we could get a house over there, and how there were many travelling families – the Joyces, Keenans and Wards – there too. It was so different – I’d never seen a coloured person before, for instance – but living was not a whole lot easier then. The better times had long gone and it was a lot harder to get work than my father had expected. He found work on building sites but having his family with him made the experience harder this time. People were prejudiced against us, although not because we were travellers – we were just Irish to them. There were some who’d call us ‘tinkers’, which never bothered me much as I didn’t really know what it meant, but I was happy when we returned to Ireland. My father sold the van and bought a truck and a car. As he was the only driver, he’d put the car on the back of the truck and hook the caravan on the back of the truck, and set off like that along the roads around Dundalk again.

People in Ireland, I learned, could often be just as prejudiced as the English. We met so few other children from outside the traveller families – mainly the farmers’ children who came to see us when we moved onto a site – so we kept very much to ourselves. Not long after moving back from England my father bought a new caravan – well, new to us anyway – and it had a battery in it that could power a little 12-volt black and white television. Sitting in the trailer watching TV by the side of the road was a great thing.

I was happy going back out on the road. Lots of the sites were familiar to me and I knew where to find little hiding places and where to make dens for myself. I never thought life would change; the most my family ever wanted was a nicer car, a nicer caravan. We’d put up somewhere for the winter and be joined by other families who, like us, would travel the roads during the warmer months but rest up for the colder ones. I liked to see new faces, as much as I loved my family I could also get a little sick of the same old thing every day. Even though I had three brothers and three sisters and we all got on like a house on fire, it was still great when someone new to us was nearby. I loved to see someone different pull in beside us, strangers who might be part of the clan but still people we hadn’t seen for months. For me the great thing was that our games could be more involved because there were more youngsters joining in.

Come the spring the three or four families would each go their separate ways, and we’d move about, never sure who we’d find ourselves alongside for the night. In those days there was never any trouble between the clans; we were always careful, but the times were easier. It was only when travellers started to give up the travelling life that everything started to get more difficult. That began to happen at the end of the 1970s, when the recession hit and there was little or no work, and the only money my family had coming in was the social security. The lack of work hit everyone, not just travellers.

In 1979 I went to the horse fair at Ballinasloe, over in County Galway, with my father; it was a great experience for me but he didn’t enjoy it. My father was the kind of a man who never liked trouble, but there was always trouble at the fairs, so he avoided them if he could. As soon as we saw some fellows picking on each other, trying to provoke a fight, he said, ‘Right, Jimmy, we’re off,’ and that was it. I’ve never been to a horse fair since.

Chapter 2

BOXING GLOVES

One thing that never really featured highly in my childhood was school. Like most traveller children, what I needed to learn I learned from my father out in the fields and hedgerows. The only point of going to school, as far as travellers were concerned, was to prepare a child for their Holy Communion and Confirmation by learning about religion.

My first school was the primary school in Mullingar run by the Christian Brothers. Travellers weren’t well looked after in school and I discovered it was no different at the one I attended. In the last few years the Christian Brothers’ schools have come in for criticism and I’m right behind what has been said about them. Our teacher, Brother Reagan, was a priest, and what he used to do to the small children in his class was not at all nice. He had a thick black strap, what we called the black taffy, and if he felt you needed it, he’d make you stick out your hand and would whack you hard with it. He would do this to kids as young as 6 years old. We never learned anything from him; we just feared and hated him. Traveller children weren’t expected to learn; we were simply a nuisance as far as Brother Reagan was concerned and he just wanted us to keep quiet and not bother him. We were never sure of what rules he had, so often we’d get the taffy across our hands for what seemed like nothing at all.

I was taken out of the Christian Brothers’ school and sent to the convent school next door. My class was taught by a nun called Sister Mary. She was a saint by comparison with Brother Reagan, but she was as well the loveliest nun I’ve ever met. All the bad feelings I’d started to have about religious people changed completely when I was in her class. Where Brother Reagan was fierce and angry, Sister Mary was very pleasant, and I felt protected by her. Yet I still didn’t learn much with her, always looking forward to being out of the classroom playing.

The school playground was full with my cousins as well as my younger brothers and sisters. One of our cousins, Theresa, was in the class below mine. I didn’t see her again until ten years later on, at my brother’s wedding – and I had to be reminded who she was. Within a few days of that meeting she’d agreed to marry me.

When I’d been at the school for a while I was moved up into the next class and I stopped learning altogether. But my experience wasn’t quite as bad as my brother Paddy’s. He and several cousins, boys from the Joyces and Nevins, as well as our cousin Sammy, all roughly the same age, were put into a pre-fab building by themselves at their school. There were no desks, just a few chairs for them to sit on. ‘Here you go, lads,’ said the teacher, handing them a pack of cards. ‘Keep quiet till break time.’ That was their education, five days a week. On other days, they’d be led into the playground when they arrived in the morning and told to get on with kicking a ball about, but not to make too much noise or they’d disturb the children from settled families, who were all in class learning.

That I never learned much at school wasn’t just down to my being ignored by the teachers, or not caring; it was also because I never stayed in one school long enough. When I’d been at the school in Mullingar for a while, my father came home one night and with absolutely no warning said, ‘I’m moving us to Dundalk.’ We moved the very next day and after we’d settled into our site I was taken into a school in Dundalk, another school run by the Christian Brothers, but much better than the one in Mullingar. No one chased us to find out why I wasn’t at school; the school I had been at had no contact with us, as we had no phone and no forwarding address. No one came round to the site to see if there were any children who should be at school; the system wasn’t interested in forcing traveller children to attend school. Why should it be? We weren’t going to be doing anything with what we learned; we would be out in the fields long before the other children would be just starting to study for their exams. Travellers wouldn’t use what they might have learned because they didn’t get jobs that needed an education. That was the attitude people had then. Maybe the authorities also knew that the reason I was going to school was for what I would be given – free uniform and free shoes.

All I could tell my new teachers about what I’d learned was where I went to school and what class I had been in. I couldn’t remember what I’d learned and I still couldn’t read or write, so whenever I started a new school I was always put into the first class. They never asked me, who was your teacher, how far did you go through the school? Whatever picture books I’d been given were gone, left behind, and that was one of the main reasons my reading and writing never improved. No one at the school ever tried – as far as I know – to contact the previous schools to see what records about me they had. The teachers at each new school seemed to think it was ‘easier if we start again, James’. Which meant I never made any progress.

The time that most upset me was when I was taken aside at school and asked about my family. I didn’t know what the teacher was getting at until she used the word ‘adopted’. I couldn’t work out why, but it was because my father called himself Jimmy Quinn and the teachers had my name down as James McDonagh. I didn’t know this at the time because nobody explained things like that to me, and I was left to puzzle it out for myself.

We moved again, this time south. I was put in a school, in the middle of Cara Park, a traveller site in Coolock, where there were a few pre-fab buildings in the centre. One of these little units was a school for travellers, and us young lads went there. There were about six or seven of us of the same age going through the last stage of school at the same time, and this is where the one thing that did change things for me came about. The school at least showed some interest in getting me through my religious education, and a little nun educated me for my Confirmation. Sister Clare gave me all the prayers I needed and told me how to respond to the questions I was asked.

The day came for my Confirmation, and that day I wore a blazer. My father and mother were there, watching proudly, as were other traveller families because others were confirmed at the same time. One of them was my friend Turkey’s Paddy; we’d got on famously since we’d met. Not long afterwards his family moved on to Newry and he went swimming in a river and drowned. Turkey’s Paddy was buried in Dundalk. His mother, Maggie, came over to me at the funeral and said, ‘James, you and Paddy will never play together again,’ and I cried. I was still only a child and I’d never before experienced losing someone that close to me. I just didn’t know what that meant until the moment Turkey’s Paddy’s mother spoke to me at the funeral. She knew how close the two of us had been, and as a token of that, when she had her next child she called him James.

As soon as I could after I was confirmed, I left school, and we went away and travelled. As a travelling family was mostly moving around in the summer and working in the fields in the autumn, there wasn’t a lot of time for me to go to school anyway. I left school at 12. I’d never liked it.

My mother had only sent me to school to be prepared for my Confirmation, and once that was finished she didn’t care any more about my education. People care now. As a parent now myself I have very different feelings about education. The times have changed and what was considered OK then would not be allowed now. Back then, traveller kids were considered second class, second rate, and it didn’t interest those in charge that we weren’t getting an education. Travellers are no longer left behind and ignored in classes; in some schools, like the one my sons went to in Dundalk, there are classes just for travellers. Some see this as special treatment but I don’t, because I think traveller children have a long way to go to catch up with settled children, who are used to the idea of school, expect it, and welcome it. It will take a long time for education to become a habit for all traveller families. You can’t make that happen just by wanting it; you have to change the way everybody else thinks about it too, and that is a long-term project.

In later life I taught myself to read and write, but as a young boy the only thing I liked about school was learning about religion. All traveller families are religious, some more than others perhaps, but they all believe in God. Some may be sarcastic about it, they may do wrong, but they also believe in Holy Mother Mary and in Jesus Christ. That has never left me; as an adult I have even been on pilgrimages overseas, to Fatima in Portugal, for instance. A lot of travellers go to Lourdes. I try to attend Mass every Sunday. I believe in Heaven – that when someone has been good they will go there – and I believe in Hell. I believe in a lot of angels. The Holy Trinity is tattooed on my back. Religion is probably the most important constant in traveller life, and all families bring their children up to believe in God and to go to Mass. A newborn child must be christened, because travellers believe that a child doesn’t prosper or improve until they get that original sin taken away from them by being baptised into the Church. We pray for those who have died, we pray for their souls, we pray for each other. My wife is a very religious person. Theresa will say the Rosary every day and she will never miss Mass. She’ll walk five or even ten miles to attend.

Although I’d left school I was still unable to go and join my father in his work – I was too young – so instead I had to work at a training centre for young travelling kids. AnCo was the name of the organisation, and they would teach me a skill that would enable me to become an apprentice in a job. I chose carpentry but it was never really my thing. I did it for a while, mostly because I was paid £30.30 a week to stay on there at AnCo.

The first week I had that money in my hands I went out to spend it right away. When we were doing the farming work, all we ever got was pocket money because all that we were earning was needed to keep the home going. It meant so much to me to have my own money to spend at last. I knew what I wanted to buy first: a bike. That way I could get out, go anywhere I wanted. The second week, I bought a tape deck so I could listen to music. The third week, I bought some clothes: Shakin’ Stevens was big then with his hit ‘This Ole House’ and I bought some clothes like his. White trainers, tight jeans, a Levi jacket, black shirt, white tie: that was Shakin’ Stevens’s look on his album cover and I got it. But it wasn’t a Shakin’ Stevens record I bought first; it was Rod Stewart’s ‘Baby Jane’. I liked Rod, still do, and country and western too, and we’d dance to the records at the teenage disco that was held on the site once a week. I was happy with what I was doing: I was earning some money, I spent Friday nights at the disco, and the rest of the weekend hunting. And I went boxing.

I’d started boxing for two reasons. The first was that I hated being pushed around by other kids, and from a young age found myself bullied. Certain settled kids in Mullingar were bullies; they were a clan of their own, and a little gang of them would go about the place trying to find someone to pick on. They’d never value anything we said or did. That has all changed since those days, and when my sons were at school they learned that settled kids often look up to traveller kids. But it wasn’t like that when I was young. If a game of football or of handball was going on, I’d go to join in and these kids – who weren’t playing themselves – would stop me, push me off the field, and hit me. If they were playing and it was our turn to play, they’d push me away, kick me up the arse, shove me, slap me on the head. They would hit me hard enough to make me cry, and crying is embarrassing when you’re that age. No one would stop them because they knew that they’d get the same thing if they tried.

It wasn’t just settled kids who were the problem. I remember one time at Cara Park, I was playing with two friends on the roof of a pre-fab. Another kid came along, older than us but shorter, and told us to stay up there or he’d punch us. We were that petrified of him that we stayed up there on the roof even when he went away, and only crept down when it got to about two in the morning. There we were, the three of us, all taller than him, and we still wouldn’t come down. That’s the power bullies have over people.

I didn’t have many friends then. I’d make friends easily, but if we didn’t move off after a few weeks, then their families did. When you’re that age you really look for someone to be your friend, especially if you feel you’re picked on otherwise. So perhaps it wasn’t a surprise that I fell in with some people who lived near Cara Park, in Belcamp House, a mansion that later burned down. They were a charismatic Christian group and I started going there just for the fun of it and then really got into attending the prayer meetings and other events they organised. I made some good friends there and for a while I became very serious about being involved in their kind of Roman Catholicism. For two years I was going to prayer meetings on Tuesdays and Thursdays, as well as Mass on Sundays. Saturdays we’d meet for bible study. It’s a surprise that I had time for anything else.

My greatest friends at Belcamp House were an American family called Cullins. Brendan Cullins was around my age and became my particular friend. The family moved back to the States and – it just goes to show the difference an education can make – Brendan went on to be a brain surgeon, while I ended up someone who goes to country lanes to bash people in the face for a living.

As kids we’d always boxed a bit. We couldn’t always play football or whatever game we wanted, but boxing was something else we could do near to the site. When we came back from picking spuds or wherever we’d been, if there wasn’t time to run off and get a game going, we could stay by the trailer and box. I’d always known I wasn’t very good at football, much as I liked to run about. I was always last to be picked to go on someone’s team, and when there’s fifteen to twenty kids standing on the pitch waiting to get the game going, this can be embarrassing. I was always the last one chosen because everyone knew that no matter how hard I tried I couldn’t kick a ball. It made me feel some kind of wimp that I couldn’t kick a football straight. To this day I think I must have been the worst footballer of any traveller in the world. Trying to play handball was no better. No one would play doubles with me, even though I liked the game. They didn’t want to waste their time because again I couldn’t play it.

Just about every sport I was rubbish at; so when I realised that I could throw out my two hands well, I was pleased. I don’t know whether people were happy for me that I’d found something I could do, or if they were just being polite, when they said, ‘You know, James, you’re not bad at that boxing there,’ but that motivated me. I’d finally found something that I enjoyed and that people liked seeing me doing. It would be big-headed of me to say I was good at boxing right from the start, but I’d found something that I was better at than most other people. I only took it up in the first place because I could do it and because I thought that if I was any good I could use it to stop being bullied – I had no idea where it would take me in the end. I just wanted to be able to look after myself in years to come.

My father never had a fist-fight in his life. His brother Chappy was known as a man to have had a few fights, but not my father. If my father got into trouble, Chappy would step in and take his place or go and sort it out. He had done a bit of boxing – or a bit of fighting, shall I say – but no training. So I’m not sure why my brother Paddy and I took to it so well. I just know we did.

When I was 10 and Paddy a year or so older, we were given boxing gloves for Christmas. Paddy loved boxing from the moment he started; he still loves it to this day, and although he’s a bit old to do the training now, he still has the head for it and knows what he’s doing. As Paddy’s sparring partner, it took me a while to do more than just stand there and block his punches. But eventually I did, and that’s when people noticed I could box quite well. So I was sent along to a club to train and learn to box properly.

Paddy started to box regularly at a local gym in Dundalk. When he went for his training sessions I would sometimes go down there with him. At first I felt out of place – the other boys seemed more powerful than me and I was long and skinny then – but after a while I got to like it. I started feeling fitter from all the training I did and once I had learned to protect myself properly I really started to enjoy the boxing itself.

I joined the Dealgan Boxing Club and I trained there for about a year and a half before we moved too far away for me to travel there easily. Then, when we moved to Cara Park, I carried on my training at the Darndale Boxing Club in Coolock, where they produced great boxers like Joe Lawler, who fought in the 1986 Olympics. There I learned how to move when boxing, how to breathe – not as simple as it sounds – and it was there I would have my first fights. The first thing the trainer, Joe Russell, taught me at Darndale was to breathe in through my nose, out through my mouth. ‘James,’ Joe said, ‘every chance you get, hold back, get the breath in your body. Stand off a little, not so far he notices but far enough to give you a little time to breathe. Take every chance you can. In through the nose, out through the mouth. Don’t show you’re breathing, like this’ – he would breathe heavily and fast through his mouth – ‘don’t let them know. Just step back and be on your foot, be on your back foot, be on your toe.’ Joe would demonstrate by standing tall and breathing deeply through his nose. ‘Side step. When you feel tired, you know, just step back a little bit. Drop the hand. Let the blood flow back in. If you hold it up for five minutes it gets tired. So you have to just pull it back in and relax.’ Now Joe was talking about fighting in a ring, where there are breaks to let you recover your breath and lower your guard. Years later, when I was fighting out in the air with no ropes and no breaks, his advice was still the best I’d been given. Rest, and breathe, whenever you can.