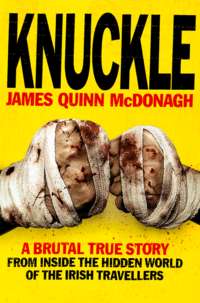

Knuckle

The boxing club itself was a place I liked to go to, because the people there had an attitude towards us travellers that was completely different from what we’d encountered at school. Schools hadn’t been very good to us, whereas the boxing club welcomed us in. Having someone teach me who encouraged me to improve every time I came in – a new experience after my years at school – meant not only that I started to enjoy my boxing, but that learning came easily to me. In addition, the training did a lot for my strength and my physique. I found aggression that I didn’t have outside in the world would come to me when I was in the ring. At first I wondered where this came from, because outside the ring I thought I was a normal person, but when I stepped into the ring it was a different story. Perhaps it was because with the gloves on and someone in front of me wanting to hit me, I became a different person.

Young traveller lads on the sites we stayed on were often keen to take up the sport because it meant they could say to themselves and their friends, ‘I can handle myself, I can box.’ Sometimes boxing clubs would have as many as ten or twelve travellers as members, but as usual they would come and go, depending on where their families were living and working and whether or not they could keep up the training. Me and Paddy were the most persistent two in the club; we stuck it out for a good few years, Paddy longer than I did. My younger brother Dave joined us in the club and he too was a good boxer, but he never kept it up the way Paddy did, or went out onto the street with it the way I did.

At the club I made good progress and was paired up with Joe Lawler as my sparring partner. He was about my age but a lot lighter than me and a lot smaller too. To be honest, Joe was my biggest nightmare there. He had a right-hand punch that I couldn’t seem to avoid, and when he hit me with it I was always taken by surprise because it was phenomenally hard. He would jump up slightly and sling his hand forward, and I’d see it coming at me, riding over the top of his reach until it connected with my head – bam. I don’t think he’d be allowed to use it now, but he’d just sink it on my head and I’d feel my brain pounding. Joe was brilliant: I watched him win nearly fifty fights with a knock-out, and in all of them that right hand of his made the difference. I used to dream about that punch, it preyed on my mind so much.

The first time I stepped into the ring for a competitive fight I wasn’t successful, but as it was my first fight I hadn’t had any experience, so I wasn’t disappointed that I lost that one, and besides I knew I’d fought very well. But the next fights went my way: I won every one of the following thirteen, both club and competition fights. Ten boxers would be picked from each club and put into the ring to fight each other. The biggest fights for me were when I fought for Dublin against Galway, Cork and Limerick in the under-18 County League as a little scrawny ten-stone welterweight.

I didn’t win my last County League fight, though, against a guy from Omagh, in County Tyrone. A Northern Ireland champion, he was four years older than me, bigger than me, stronger than me; and at that age those four years can make a lot of difference. But everyone said I had balls to go into the ring with the guy and so I felt some confidence before the fight. And I went into the ring and fought well; although I lost I didn’t embarrass myself. My trainer said, ‘James, well, you know you lost, though to me it was a fifty/fifty fight but the judges went against you.’ I knew he was trying to pick me back up, but the feeling of losing that fight was pretty bad. But at least I knew I’d been beaten by someone bigger, stronger and more experienced. If I’d lost to someone I didn’t feel had those advantages over me, I’d have been almost suicidal. I understood then how much I didn’t like losing, and it was something I hadn’t realised until it happened.

I didn’t yet think I could make anything of myself as a boxer. I enjoyed it and wanted to carry on but at that time it wasn’t something I thought I could carry on for ever. This was down to my family life; I knew that at any moment we might move away from Dublin and I’d no longer be coming into the gym. I had a couple of competitive fights coming up, one in Dublin and then – if that went well – a tournament in Leeds where I’d be representing Ireland – when my father told me we were leaving the city.

We had been living in a little traveller housing scheme in Coolock, but my father told me he needed to move again in his hunt for work, because there was none anywhere in the Dublin area. I didn’t know it at the time, and it wouldn’t have meant anything to me then, but Ireland was going through a deep recession. Back then most travellers didn’t know what a recession was. Now they can see that a recession affects all walks of life, but at that time, like most people, they didn’t know anything about politics or economics; all they knew was about surviving, day-to-day living. My father decided that we’d try our luck in England again, so my time in the boxing club was over.

Some years later I learned that there was more to it than this, that my father had had a dispute with my trainers at the club. I don’t know who this dispute was with, and I don’t know what it was about, but he had fallen out with someone at the club. He told me many years later that it was due to some perceived favouritism at the club – that he wanted me to face someone else but the club had reserved that fight for another boxer, and he felt I was being overlooked. I don’t know the ins and outs of all this and I wouldn’t like to speculate, but I don’t resent what happened. All I do know is that I was due to take part in the biggest fight of my life so far – I would have won a national title if I’d won that fight – and we were going to move abroad before it could happen.

I wish now that I’d been given a chance to pursue that boxing career, to see whether it would have taken me along a different path than the one I ended up on, and whether it would have got me a career inside the ring. I believe I could have done something with the boxing. I believe that I could have faced the challenge. I wasn’t a sports person, so to find a sport I liked, one where I could control the opposition and do what I wanted with them, made boxing very exciting to me. I was good as a boxer and I wanted to carry on with it. I don’t know how far I could have gone but I would have loved to have had the chance to find out. Perhaps then I wouldn’t have found myself boxing out on the street.

Chapter 3

ENGLAND

My father hitched up the caravan and we all set off to England on 13 April 1984. The ferry runs from Dublin to Holyhead in Anglesey, off the north-west coast of Wales, but we weren’t expecting to stay in Wales for any length of time but to drive straight on into England. When we got off the ferry, though, my father was taken to one side; it turned out that he was banned from returning to England after he was imprisoned there in the 1960s. He was supposed to stay out of the country for twenty-five years, he was told. He said he had no idea that the ban was still in force but no one took any notice of what he said and he was taken off by the police and put into a cell to await an appearance in court.

We were stuck in Holyhead. We couldn’t leave without my father, as we didn’t know if he was going to be locked up again, told to leave the country, or what. My mother was in distress. We got in touch with some of my father’s relatives and they came to see how he was doing and whether or not there was anything they could do to help us. It was my uncle Johnny Boy, my cousin Joe Joyce, and his cousin Tim Joyce who came to see us. Paddy was 17, I was 16, and the three of them took us to the pub. We had a few drinks and then went to see my father. The policeman who took us to the cell said, ‘Lads, there’s no problem, really. He’ll go to court and they’ll deactivate the banning order and he can come out. If he’d committed crimes in Ireland it would be different, but as it stands there’ll be no problem.’ And he was right: after a couple of days my father was released and we were back on the road again.

We headed to a little village called Wing in Buckinghamshire, between Aylesbury and Leighton Buzzard. This is where my uncle and cousins had come from to see us in Holyhead. We stayed there on their site with them for a couple of months and then moved on to Eye, outside Peterborough, where we stayed in a lay-by.

My father and my cousin would go out looking for work together – we call it hawking. They’d spend the day hawking and then, if we were lucky, they’d come back having got themselves some work for the next day. It might be shifting something in the van, or laying tarmac on someone’s drive. If anyone needed labourers, Paddy and I would do that. They were the foremen – we were the workforce, the ones actually doing the work. Except when it came to laying tarmac; you had to be skilled to do that, not because the work required it, but because the skill came in making money out of it. The thinner the layer of tarmac you laid the less your outlay, and that’s where you made some profit. The older men were far more experienced than me and my brother at getting the thinnest layer possible, so they did that work, while we cleared the ground and kept the tools hot in the fire. That’s not to say we’d do a bad job – my father and Joe were proud of the work they did – but we weren’t doing it for love but for money. And once we had one house in a street getting their drive done, then Paddy and I would be up and down the road, asking people if they wanted theirs done too, ‘because we’re in the area doing your neighbour’s drive and we’ve a little tar left over’. That worked a treat every time.

Meanwhile I found a boxing club to go to, the local one in Leighton Buzzard, in Bedfordshire. When I had warmed up a bit my first time there, the trainers asked if I’d go in the ring and spar with their top boxer, a 17-year-old ABA season champion. I don’t know why they asked me. Maybe they’d run out of sparring partners for him and wanted fresh meat. I suppose I can’t have looked much of a threat to him, as he was massive, like a fully grown man, with a crewcut and tattoos, and there was me, a scrawny thing of about ten stone, slightly younger than him to boot. But I’d forgotten to mention to them how much fighting I’d done in Dublin, so I had that up my sleeve, and when we got into the ring I punched this lad around the ropes, and in two or three rounds I took him apart. I kept him away from me, so he couldn’t touch me, and when I stepped in and hit him I got my punches away cleanly. He was livid but the trainers were delighted. They wanted a proper test for the guy, and they thought they’d found another boxer for their stable. ‘Have you boxed much before?’ someone now bothered to ask me. ‘Well, a little,’ I told him. ‘A year or two in Dublin. I won a few fights for the club.’ He studied me a bit. ‘We’d like to enter you for some fights here, you know.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов