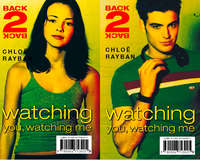

Watching You, Watching Me

Melanie deserved the all-time poseur prize because she’d been to the South of France and stayed on her uncle’s ‘yacht’ (i.e. power cruiser, but nobody was splitting hairs). Loads of people had been to Spain and were sporting tans to prove it. Jayce, the rebel of the class, claimed to have been on a caravan holiday with her boyfriend and went into a huddle with some of her mates over the steamier details. Rosie had spent two weeks in Tenerife with her Mum — she’d met this boy and had brought in tons of photos.

I just kept my head down. No-one needed to know about our two-week family walking tour along Hadrian’s Wall, did they? I’d enjoyed it, actually, in a masochistic sort of way. The weather had been fantastic and we’d taken field glasses and seen curlews and sparrow hawks and one day we’d even sighted a falcon’s nest. But I knew from bitter past experience that the very mention of bird-watching would bring the united weight of class scorn down on me.

I’d done an essay, a year or so back, about what I’d done on holiday, and got an A for it. I had to read it out to the whole class with Mrs Manners looking on and smiling indulgently. Dad had taken us to a place called Holy Island. It’s not really an island — its at the end of this causeway, but it’s cut off at high tide. It’s got a castle and an abbey but absolutely nothing else except marsh and sea and birds. I’d felt myself getting hotter and hotter as I read out all this stuff about the abbey and the monks and the curious sense of history in the place. I could hear people fidgeting and giggling beneath the sound of my voice.

That’s when I got friendly with Rosie. She’d come and found me in the cloakroom where I’d gone to get some peace. There’s a place between the coat racks where nobody can see you if you sit really still.

‘It’s OK for you,’ I said, blowing my nose on the tissue she’d given me. You went to Majorca. You’ve got a tan and everything.’

‘Yes, and Mum went out every night and I had to stay in this stuffy hotel bedroom and watch crappy films on the TV. The hotel was full of grossly overweight middle-aged couples getting sunburn round the pool — the women looked like red jelly babies and the men looked like Michelin men and they were all trying to get off with each other. It was disgusting.’

‘You didn’t put that in your essay.’

‘Course I didn’t, stupid.’

Rosie was brilliant like that. She didn’t tell lies exactly, she just knew how to present the truth in the right light for class consumption. If she went to Calais with her Mum on a day trip, she’d let drop that they’d popped over to France for lunch. If a boy asked her out she wouldn’t say he was fit exactly, she’d just find the right way to describe him. I’d got to know her shorthand and how to translate. Tall for his age (i.e. overgrown and weedy). Fascinating to talk to (i.e. gross to look at). Really fit and into sport (i.e. totally obsessed by football).

Anyway, unlikely as it seemed, Rosie and I had teamed up. I had an ally, a conspirator, a protector. However gross the girls in class might be to me, I always had Rosie to have a laugh with.

She was beckoning wildly to me now as a matter of fact.

‘How come you were so late in?’

‘Mum nearly ran someone over. This really gorgeous guy on rollerblades.’

‘She should’ve driven faster — you might’ve got acquainted.’

‘That shouldn’t be a problem. He’s moved into our street.’

‘You’re joking — a fit guy in Frensham Avenue?’

‘Stranger things have happened. Except we think he’s a squatter.’

‘In good old respectable Fren-charm.’ (She was putting on a posh accent). ‘All the local budgies will be falling off their perches in shock.’

‘Yeah well, we’re not sure yet.’

‘I better come’n check him out — like tonight.’

‘OK, you do that.’

I had double Biology at that point and Rosie went off to General Science so I didn’t see her again until after school.

Chapter Three

There was a kind of unspoken feud going on between West Thames College and our school. Our school is an all-girls comprehensive, and it has quite a reputation for getting people into university. I guess the West Thames crowd look on us as swots. We return the compliment by considering them losers. Our status isn’t helped by the fact that we have to wear uniform until we’re in the Sixth Form. So the galling truth — that you’re only in Year eleven or below — is positively broadcast to the nation every time you walk down the street.

On my walk home I always came across groups of West Thames students hanging about in the street. Generally, I tried to ignore them. But today I took an interest. I was hoping to catch a furtive glimpse of our squatter. Most of the students were a lot older and a lot more chilled than us. There was a load of them crowding round a café having a laugh. The girls looked really sophisticated, more like art students. I crossed over to the other side of the road. It was really humiliating to be seen by them wearing school uniform. I’m pretty tall for my age so I look twice as ludicrous as the average girl in mine. My legs are so skinny my gross grey socks slip down as I walk. I could feel them right now subsiding into sagging rolls round my ankles. But there was no way I was going to stop and pull them up with the present audience.

A searching glance through the crowd revealed, to my relief, that there was no-one of his height or colour in the group.

I was continuing on my way down Frensham Avenue dressed in this totally humiliating way when I had that feeling again. The feeling of being watched. The closer I got to home the stronger it got. I glanced up at number twenty-five. I couldn’t see anyone at the windows but I felt positive he was looking down — watching me.

I got inside as fast as I could and slammed the front door.

‘Hi Tasha — want some tea?’

‘No thanks. I’m going upstairs to change.’

‘Have a cup first.’ Mum appeared round the kitchen door. What’s up? Had a bad day?’ It never ceases to astonish me how mothers have such an uncanny knack of reading every tiny intonation in your voice and then drawing a totally inaccurate conclusion.

‘I just want to get out of this,’ I said, indicating the uniform.

‘Have a shower — you’ll feel much better.’

‘Mmm.’

I dragged my clothes off and climbed into the shower. I washed my hair. I let the water run down through my hair and over my face and I did feel better as a matter of fact. I felt as if I was washing away my dreary day and that terrible vision of long lanky me in saggy grey socks. The person who emerged from the shower was new and clean and not half-bad actually — wrapped in my white towelling robe I felt like someone quite different.

I went and lay on my bed for a while in order to savour the feeling. I’d just spend ten minutes or so chilling out before I got down to my homework.

I lay there staring at the ceiling. That guy over the road was just so — fit. I’d never stand a chance. I mean, he was surrounded by dead cool girls, wasn’t he? He’d never be interested in me. Then I got to thinking about that word ‘cool’. The trouble is, if you’re like me, the minute you’ve got the hang of it — like the right clothes and music and language and stuff — you find the whole scene has moved on. And whatever it was you thought was ‘cool’, isn’t any more.

In fact, the truly sad thing is, the harder you try to be ‘cool’, the more it evades you. Like that ghastly time the girls at school were talking about their favourite film stars. I thought I’d be really ‘cool’ and mature so I said Ralph Fiennes. And everyone fell about. I didn’t know you were meant to pronounce his name ‘Rafe Fines’. It would have been simpler if I’d just settled for Leonardo diCaprio or Brad Pitt like everyone else.

One day I’d show them all. I’d be so damn ‘cool’ that everyone would be absolutely begging to come round to my place. I’d have one of those mansions in the hills in LA — all white with pillars and palm trees and a couple of marble swimming pools and a drive-in wardrobe. And I’d give this massive party with guys in uniform ushering limos in. I’d be standing there on the steps wearing this incredible designer outfit with Brad Pitt on one side and Leonardo diCaprio on the other and ‘Rafe Fines’ lurking enigmatically somewhere in the background being incredibly mysterious. All these girls from school would drive up and I’d look at them blankly and say: ‘Hang on a minute — do I know you …’

‘Hi … I’ve come to check out your horny new neighbour.’

Rosie woke me up!

‘Oh no! What’s the time?’

‘Seven-thirty. You look so you’ve been hard at work, I must say.’

‘How did you get up here? Mum in a coma or something?’

My parents generally went ballistic if anyone interrupted the sacred homework hour.

‘Nah, told her we were doing a project together — official visit. So I’ve come to see what he’s like. I hear he’s got a really fit body.’

She had moved over to the window and was staring out in the most obvious fashion.

‘Get away from there, he’ll see you. How come you know so much about his body anyway?’

‘Your kid sister’s put out an official statement. Only a matter of time apparently before you two are an item. She’s chosen her bridesmaid’s dress already.’

‘Gemma! Uggh … You can have no idea what a pain it is to have a younger sister. I’ve absolutely nil privacy. I fantasise sometimes about being an orphan with no family whatsoever. You don’t know how lucky you are.’

‘Yeah well, but brothers and sisters can take the pressure off. Being an ‘only’ means Mum’s investing all her hopes and ambitions in me.’

‘Huh — you can wind her round your little finger.’

‘That’s technique. Taken years to perfect. Sod-all going on over there — budge over.’

Rosie grabbed a pillow and settled herself down end-to-end on my bed. She leaned over and shoved a CD in my player, then sat well-prepared for a girly chat.

‘So … what is he like?’

‘Turn it down a bit — they’ll hear.’

‘God, I’d give anything for a ciggie — do you think they’ll notice?’

‘Yes, Dad’s got a built-in smoke detector up his nostrils.’

‘OK, shoot. Is Gemma making it all up? Said he looked like that guy who used to be on Blue Peter — you know …’

‘Tim Vincent? The one she nearly died of a crush over? She needed counselling when he left the programme …’

‘Well is he …?’

‘Nah. He’s a bit more mature-looking than that. Not so baby-faced.’

‘Mmmm … Tell me more.’

I suddenly had an insight that if Rosie got in on the act I wouldn’t stand a chance.

‘I didn’t get that good a look at him. Not that fit. Maybe he had dandruff …’

‘You must’ve got a pretty good look at him to notice that!’

‘Look, hold on — we don’t know a thing about him! He’s a squatter for God’s sake and he’s probably really rough. He goes to West Thames.’

‘A squatter who goes to college?’

‘Well, seems like he was going there this morning. I guess it is a bit odd.’

‘Maybe he’s a cleaner there or something.’

‘Mmm.’

Rosie had grabbed my eyelash curlers and was studying her reflection in my hand mirror. She was concentrating on putting the curl back in her lashes.

‘Hey … Something is going on over there.’ She stopped with one lash done — the hand mirror was trained over her shoulder.

I craned towards my window. The boards which had been nailed up over one of number twenty-five’s upstairs windows — the one at the very top, opposite mine — were being split apart. It looked as if someone was trying to break through.

Rosie had leapt from the bed and was hovering by the window.

‘Do we have a sighting?’ I asked.

‘Uh-uh, nothing yet,’ Rosie whispered, waving a hand at me to keep quiet. Then she added: ‘Down lights. Down music. Action!’

I switched the bedside light off and joined her.

The squatter was leaning out and wrenching at one of the boards which was proving hard to shift. He was wearing a torn old T-shirt. The light of the street-lamps had just come on and were catching him from below like footlights.

‘I thought Gems was exaggerating. But he is really scrummy.’

‘Isn’t he just?’

‘So why aren’t you in there, man?’

‘How?’

‘Head over there with a cup of sugar. Enrol him into the local Neighbourhood Watch. Sign him up for the Brownies. Use your imagination!’

‘Small problem.’

‘What?’

‘Mum and Dad have already decided he’s big, bad and not-nice-to-know.’

We were interrupted at that point by a loud ‘Cooooey’ from below. ‘Supper-time!’

We made our way downstairs.

‘Do you want to stay, Rosie? There’s plenty to go round.’

Rosie eyed Mum’s veggiebake, which was standing steaming on the table.

‘Thanks Mrs Campbell, but Mum’s expecting me back.’

Mums cooking was a bit of an embarrassment. I mean, there’s a limit to what you can do with vegetables. I expected Rosie and her mum were having one of those lush M&S meals. I’d seen inside their freezer, it was stacked with stuff — ready-made meals all with posey foreign names. Some people had all the luck.

But it was one of Mum’s better bakes. As a matter of fact, I even had a second helping. When Dad had eaten enough of his meal to put him in a receptive mood, I took the opportunity to ask a few questions.

‘What happens to squatters, Dad? If they’re caught? Do they get fined or go to prison or what?’

‘It depends,’ said Dad. ‘If the property’s derelict and they’re in there long enough, they can establish something called ‘squatter’s rights’. Then it can be really difficult to get them out.’

Gemma eyed me over her food. This was good news.

‘But there must be some way to get rid of them,’ said Mum.

‘If you can prove they’re causing damage or are a nuisance you can.’

‘This one’s not a nuisance. He’s quiet as a mouse. He doesn’t even have lights on,’ said Gemma. ‘I think he’s lovely.’

‘Stop messing about with your food and eat it properly,’ said Mum irrelevantly. Her irritation showed in her voice.

‘I don’t like the horrid black bits. They’re all wibbly.’

The black bits are aubergine and there’s no such word as ‘wibbly’,’ said Mum.

An argument broke out as to whether or not ‘wibbly’ was in the dictionary and Gemma insisted on finding it to check. So the subject was dropped for the time being.

Post-dinner Gemma was on drying-up duty, so I headed back upstairs as fast as I could.

‘Haven’t you forgotten something?’

Mum’s voice floated up from the kitchen.

‘No … what?’

‘Your turn to empty the green bucket.’

The green bucket — the yukk-bucket, or ‘yucket’ for short as we’d renamed it — was Mum’s big bid to save the world. Absolutely everything that didn’t get eaten went into it — the more disgusting the better. Every day it had to be emptied into her compost-maker. This stood in the front garden like a great green dalek. Other people had bay trees or statuettes or nice tubs of flowers in their front gardens. But we didn’t. We had to be different. We had a green plastic dalek standing on guard outside our house — announcing to the whole world that this family was basically peculiar.

‘I’ve got my slippers on. Can’t Jamie do it?’

‘Jamie’s on cat duty this week.’

‘Gemma then.’

‘I’m drying up.’

I tried a new tactic. ‘I’ve got to do my oboe practice.’

Mum was standing at the sink with the yucket in her hand.

‘Well that won’t take all night. What precisely is the problem?’

‘Nothing,’ I muttered and went and collected the beastly thing from her.

I shot out of the front door as fast as I could, praying that our squatter wasn’t looking out of his window at the time. I just knew he was, though. I could feel his gaze positively boring into the back of my neck. It was so mortifying.

Chapter Four

Three whole days went by and I didn’t get a single sighting of him. School was one big yawn once the novelty of starting a new year had worn off. Teachers were starting to put the pressure on. A year to go before GCSEs — now was the time to panic early — big deal. Every day I trudged home with a massive bag full of books. I reckoned I was going to look like the Hunchback of Notre Dame by the time GCSEs had come and gone.

And on Thursdays — the day I had my music lesson — I had to carry my oboe and my music as well. I’d been really keen on the oboe to start with. I’d begun learning on the school oboe years ago, and I’d begged and begged my parents to buy me one of my own. I’d even saved up part of the cost myself. At the time the idea of getting into the school orchestra had seemed the ultimate in achievement. I’d really worked hard and got through loads of grades. Miriam my music teacher had started talking about applying to a music school.

But recently I was beginning to have second thoughts. The orchestra wasn’t such great shakes anyway. Nearly all the girls wanted to play woodwind — we always had loads too many flutes — and the strings were dreadful. Now I was in Year Eleven everyone was really dismissive about the orchestra. You didn’t need to be clairvoyant to realise that playing in it labelled you as a nerd. So I’d taken to carrying my oboe disguised in a big sports bag. Weighed down like this, that I was approaching the shops.

I dropped into the shops every day on my way home from school. I’d devised this plan to survive the week by punctuating it with comfort treats. Sad but true, these pathetic little gestures gave me something to look forward to every day. Monday — first day of the week — generally left me weak from exhaustion, so I’d treat myself to a Creme Egg on the way home. Tuesday it was Pastrami Flavour Bagel Chips to eat in front of Heartbreak High. Wednesday — more than halfway through the week, so cause for body-pampering — a luxury face pack or an intensive hair treatment. Thursday — that was the day I treated myself to a magazine.

Hang on — it was Thursday today.

Rosie was reading a Hello from the racks while she waited for me.

It had become a kind of ritual that Rosie and I would meet in the newsagents every Thursday. If Rosie, say, bought Mizz, I’d buy a J17. and that way we could do a swop when we’d read them. I also had another reason for the ritual. Mum and Dad would have had an absolute fit if they knew I was spending my pocket money on magazines. Sounds pretty innocent doesn’t it? I mean, magazines — it’s not as if I was buying cigarettes or booze or hash or anything. Just think what I could be into at my age.

But it’s not what’s printed in the magazines they fuss about. It’s what they’re printed on. I said we were a pretty peculiar family, didn’t I? Well, Mum and Dad are absolutely paranoid about using paper. They reckon magazines are a total waste of the world’s resources - and as for junk mail …! Don’t start them on that. I mean its virtually a criminal act in our house to blow your nose on a paper tissue. They go on as if you’d been caught chopping down a prime sapling in the rainforest or something.

Anyway, I’d decided to keep the older generation happy with this convenient little fiction that it was Rosie who bought the magazines and I borrowed them from her. We were coming back from Mr Patel’s that evening and exchanging vital chunks of media gossip when Rosie paused and nudged me.

‘Guess who’s right behind us?’

I knew immediately without turning round.

‘Keep walking,’ I muttered to her. I’d made a big plan about how I was going to look when we met. A plan that included a major make-over, newly washed hair, sophisticated-but-subtle make-up and my latest stack-heeled sandals. Not as I was at present, in my standard gross school uniform. I even had my hair up to keep it out of the way for my music lesson. It was in ludicrous childish bunches that bounced like spaniel’s ears every time I moved my head.

‘No,’ insisted Rosie. This is our chance to get to know him.’

I could have killed her. I mean, she was looking OK — she’d been home and changed and had her new mini skirt and skimpy T-shirt on. Before I could protest further she’d stopped at the corner. She was loitering really obviously.

‘Hi …’ I heard her say.

I stood, pretending not to be there. I was just praying he’d ignore us and go past. But, no. Thanks a lot, Rosie. He had to stop, didn’t he?

Rosie was going on about how we’d noticed he’d moved into the street, as if we’d been spying on him or something — which we had of course.

‘You read that kind of stuff?’ He was staring at my magazine. I glanced down. It had the most embarrassing headline on the front. The things I’d like to do with boys’ — the kind of headline that’s designed to get you to buy the magazine but turns out to be really tame inside. It would probably be things like roller blading and scuba diving — but it didn’t imply that on the front. I flipped the magazine over.

But he’d seen it already. I could tell he thought it was really, really naff. You could see it written all over his face. I mean, I don’t take these mags seriously — they’re entertainment for God’s sake — a little light relief in my dreary week. But it was just my luck. Not only was I standing there looking like a dog’s breakfast, but I’d come across as a total airbrain as well.

‘Want to borrow it?’ said Rosie, flirting with him like mad. I stared fixedly into the distance. Somehow, ignoring him made me feel less visible.

‘Hardly — its like girls’ stuff, isn’t it?’ I heard him say.

‘So how would you know?’ asked Rosie. She was trying to be witty but the comment fell painfully flat.

‘I wouldn’t know — I mean, obviously,’ he said. And he walked off down the street.

‘Egotist,’ Rosie muttered, watching him as he turned off into number twenty-five.

‘We really made a good impression. I don’t think.’

‘Well, you didn’t have to be so off with him.’

‘If I’d had my way we wouldn’t have spoken to him.’

‘That’s what I mean.’

‘Honestly Rosie, sometimes you can be such a prat.’ I guess I was pretty fed up and I was taking it out on her.

‘So you’re the world’s expert on how to talk to boys, are you?’ she retorted.

‘At least I wouldn’t have offered to lend him a stupid girls’ magazine.’

‘That was meant to be a joke.’

‘Thanks for telling me.’

‘Oh honestly, Tasha. Loosen up. He’s not the only fit guy in the world.’

‘He’s the only one living in my street.’ I stared miserably in the direction he’d disappeared in. ‘I’m never going to be able to face him now.’

‘Oh for God’s sake, Tash. Stop being such a drama queen.’

I hitched my school bag further up on my shoulder. ‘Look, I’ll see you tomorrow, OK?’

‘If you say so.’

I strode off leaving Rosie standing there. We never argued as a rule. But this time she’d gone too far.

Chapter Five

It was some days after this excruciating first encounter that he was sighted again. But not by me this time. It was by Mum.

I was doing my French homework curled up on the sofa. I usually did this downstairs, hoping to glean a little help from Mum’s shaky command of French. She was pretty good on anything to do with food or travel.

I looked up and found her poised with the Hoover mid-way through cleaning the sitting room carpet. She was staring out of the window.

‘What is it?’

She switched the vacuum off.

‘Just take a look at that.’

‘What now?’ I was sorting a particularly difficult bit of past tense into imperfect and passé composé and didn’t want to lose the thread.

Jamie joined her. ‘Huh,’ he said with six-year-old disapproval. ‘He’s drinking out of the bottle.’