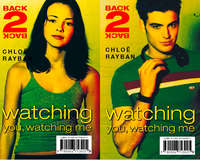

Watching You, Watching Me

Anyway, the Saturday after Matt had moved in, I happened to be up in the loft with Dad spending an ecological evening. I was helping him by sticking on rows of little green sponge trees and creating parks and open spaces. I’ve got rather fond of Dad’s project over the years. We used to get into long arguments over traffic control. I’m all for a couple of east-west one way systems which take you past all the cool shopping streets, but Dad’s plan is to filter all the traffic south of the river and ban everything from central London apart from public transport, taxis and of course, bikes. On this particular evening we’d designed a ring over-pass right round London that was like a cycle superhighway.

‘What’s that din?’ asked Dad, looking up from the calculations he was feeding into his lap-top.

It was a deep throaty boom-boom-boom that was reverberating through the loft.

‘Umm … sounds like music.’

‘But where’s it coming from?’ He was already making his way down the loft ladder.

I followed, realising only too well what was up. By the time I reached my room he was leaning out of the window staring at number twenty-five.

People were milling round outside trying to get in through the crush round the front door.

‘It’s only a party,’ I said.

‘But listen to the noise!’

‘Oh well, I don’t expect it’ll go on for long.’

‘Hmm,’ said Dad.

It was about 2.00 am when he totally flipped. I hadn’t got much sleep. In fact, I hadn’t got any. I’d wrapped myself in my duvet and sat in the window with the lights off and the curtains closed behind me — watching. I wouldn’t have believed so many people could have crammed themselves into one house. In fact, they couldn’t. There was a constant overflow of people into the garden. They were the kind of people who were a bit of a novelty in Frensham Avenue. It looked like the whole of Camden Market and Portobello Road had decided to migrate south-west. Through number twenty-fives shadowy windows you could see the waving forms of people dancing. I strained into the gloom for a sighting of Matt but it was pretty well impossible to make out anyone in the flickering candlelight.

And then, just as I was giving up and deciding to crawl into bed, I saw her — the girl who had been with him at the cinema. She’d come into the garden and she was sitting on the low wall smoking a cigarette. A few minutes later, he came out. He was standing in front of her saying something. Then he waited for some minutes with his hands on his hips while she obviously said something back. It was impossible to hear any of the discussion against the music. They appeared to be having some sort of argument. He looked as if he was about to make off when she suddenly stood up and slipped her arms around his waist. For a moment he seemed to be pulling away. But then they went into a clinch. You couldn’t really see but I could tell by the way his back was hunched they were snogging. I came away from the window and slumped miserably down on the bed.

That was when I heard Mum and Dad’s door open. Mum was saying to Dad that she’d had enough and that they ought to call the police. Dad was answering back, saying he’d give them one more chance. I heard our front door slam. I was back at the window in a flash.

But someone had got there ahead of Dad. It was grouchy old Mr Levington from number twenty. Mr Levington was about the most miserable interfering old so-and-so you could ever hope not to live next door to. A real semi-detached Sunday morning car washer. The Levingtons were a kind of family joke — Mum claimed that Mrs Levington washed out the insides of their dustbins each week. They had this garden that looked like a municipal park — a square of grass with symmetrical beds all round and all the plants tied to stakes like torture victims. Mum and Dad had an ongoing battle against their putting out noxious weed-killer and poisonous slug pellets. They were the kind of people who thought — if it moves, it must be a pest, kill it.

Mr Levington was having a go at Matt and the girl by the look of it — waving his arms around and saying something I couldn’t decipher. And now Dad had joined him. He was standing in the middle of the road in his dressing gown and slippers — cringe. The worst thing about it was Dad and Mr Levington seem to have teamed up over this one.

Dad had gone right up to Matt and the girl. Matt still had his arms around her but they’d stopped snogging. She took one look at Dad as if he was the lamest thing or two legs and then made off into the house. Matt was gesticulating, talking back. But Dad and Mr Levington stood their ground. It looked like some row. When they left. Matt went back into the house and the music was turned down.

The music stayed turned down for all of ten minutes. And then there was a crash of shattering glass and a load of shouting. The house seemed about to erupt and a kind of people-explosion burst through the front door. It looked as if a fight had broken out.

I heard Dad’s bedroom door being flung open again, and this time he did go down to the phone. I heard him dial three times and wait.

The crowd flooded out on to the street. There were about six massive guys bearing down on someone who had his back to me. He tripped and fell backwards. And then I caught sight of him under a street light. It was Matt. He was getting to his feet again, shouting things, but none of the guys were taking any notice. Then something glinted in the light of a street lamp. One of them had a broken bottle in his hand.

I stood helplessly at the window. I wanted to scream or shout but I stood frozen to the spot, afraid that any sound from me would cause a fatal lunge or slip.

And then, just in the nick of time, two police cars came careering down the road with their blue lights flashing.

I’ve never been so relieved to see a police car in my whole life.

After the police had gone the party broke up. I lay there listening as people left. At last, the final stragglers made their way down the road, kicking cans and shouting to each other and eventually singing in a slurred sort of way as they rounded the corner. Gradually the street subsided into silence.

Number twenty-five was in darkness apart from a single candle flickering in that top room. I wondered whether that was Matt in there and whether he was alone. I wondered whether he was all right. I sat watching the light for a moment. And then it went out.

Chapter Nine

I didn’t sleep too well and I was the first up next day. I decided to walk down to the newsagent and get the Sunday paper — do Dad a favour — or maybe it was just an excuse to get a closer look at what the damage opposite had been.

The whole of the front garden of number twenty-five was trampled flat, and looked as if a herd of wild elephants had dropped by. The wreckage extended into the garden next door. The ground was littered with rubbish: cans and glass from broken bottles, a shoe, a load of flyers, a sweatshirt, and the crushed packaging and scraps from a take-away meal. Then I looked back at our side of the street. The Levingtons’ house had recently been decorated, stark black and white, same as it had been before — really imaginative. I’d heard Mr Levington grumbling across the wall to Dad about how much it had cost. And there — right along the length of their pristine white front wall — someone had spray-painted the word ‘Fascist’, followed by a swastika.

I bit my lip. I’d never liked Mr Levington, he was a miserable old fogey — he was going to go mental when he saw this. I continued on my way to the shops deep in thought. The whole street would be up in arms when they took stock of the mess.

I bought a Sunday Independent for Mum and Dad and had a half-hearted browse through the mags. I needed something to cheer myself up.

Mr Patel leaned over the counter. ‘I hear you had some trouble in your street last night.’

‘It was nothing much. Someone had a party that’s all.’

‘But the police came.’

‘And then everyone left.’

‘But they painted signs. I don’t like the look of it.’

The news had got around. Even Mr Patel had heard about it. The way things were going the whole district was going to gang up on Matt. As I walked back I realised dismally — he was bound to get evicted. He’d probably move to some other squat, miles away — then I’d never get to know him.

A few doors down from the Levingtons, I noticed the house-martins were making a dreadful din. It wasn’t their usual bright chirping and whistling. They were giving out harsh cries of alarm and making dives at the Levingtons’ house. As I drew level, I saw why. Mr Levington was leaning out of the second floor window with a long broom in his hand, trying to reach up to their nest. Luckily, the ledge over that window prevented him from seeing what he was doing, so he kept missing his aim.

‘Don’t! Please don’t!’ I yelled. You mustn’t … They’ve got got baby birds in there.’

Mr Levington paused and looked down at me. His face was red from the effort and he glared.

‘They’re filthy creatures. Messing all over my newly painted window-sills.’

He stretched up again and took another swipe at the nest. He was getting nearer the mark now.

‘Stop it!’ I screamed again. ‘I’ll report you. That’s cruel! You can’t.’

The birds were getting more and more agitated. It was agonising to hear their cries of distress. I was practically crying myself.

With each swipe Mr Levington’s broom inched closer to the mark.

‘You’re an evil wicked man …’ I shouted, my voice going shrill with emotion.

And then suddenly another voice joined mine, a male voice.

‘Stop it, you bastard. Can’t you see what you’re doing?’

Mr Levington looked down and nearly lost his balance.

‘You!’ he roared. ‘I’m amazed you dare show your face in this street. Don’t move from there. I’m coming down.’

He was standing beside me dressed in an old T-shirt and jogging shorts. His feet were bare. He looked as if he’d just climbed out of bed.

‘Thanks …’ I said, my voice all husky. I jerked back the tears. The last thing I wanted to do was to start blubbing like some baby.

‘Good thing you caught him.’

His hair was all scruffed up the wrong way where he’d been sleeping on it. He didn’t look like a drop-out or a junkie, or the kind of person who got into fights. How could everyone be so horrid about him?

‘Have you seen what’s happened to his wall?’ I asked.

He half-grinned. ‘Pretty accurate description if you ask me.’

That’s when Mr Levington’s front door flew open and he strode down the front path waving his broom threateningly at Matt.

‘As for you … you vagrant! Bringing scum into this street. You get packing — out of there this very day …’

‘Look … About last night, I’m sorry it wasn’t … I mean, I didn’t …’

‘Sorry! Sorry! Is that all you can say? I’ll give you sorry …’

‘I didn’t even know those people …’

‘Filth, that’s what they were …’ He took a threatening step forward and stabbed with his broom at some greasy pizza boxes that were littering the pavement.

‘I’m going to get you out of there if it’s the last thing I …’ He moved another threatening step forward.

‘Look, I’m going to clear up a bit — OK?’ Matt leaned down and snatched up a handful of litter.

‘Clear up! You know what you can do — you can clear out …’

‘Like them?’ said Matt gesturing towards the martins’ nest. ‘Clean the place up … Is that what you’re going to do? Want to stick your broom through my house? Nice attitude I must say … Do you know how few house-martins there are left?’

I chimed in, ‘He’s right you know. It’s because of pesticides and drought … Soon there won’t be any at all …’

Mr Levington scowled. ‘I want you out of there by the end of the day … Do you hear?’

‘You know what you are, don’t you?’

‘Huh,’ said Mr Levington, turning back towards the house.

That was the point at which he caught sight of the graffiti on his front wall.

He rocked on his feet for a moment while the vision before him sank in. Then his face seemed to grow even redder if that was possible. He looked as if he was about to have a heart attack. ‘Fascist!’ he gasped.

‘You said it, not me,’ said Matt and he turned on his heel and started to walk back across the road.

Then he paused and turned back. ‘Come on,’ he said to me. ‘I think we’ve made our point.’

‘We.’ It was the way he said ‘we’ like that. It made my heart turn over with a thump.

It wasn’t how I’d planned to meet up. Ideally, I’d have liked to have decent clothes on and some make-up maybe. I knew I was looking an absolute mess but that didn’t seem to matter right now.

I followed him into the back garden of number twenty-five. He paused outside the back door.

‘I’d ask you in, but the place is not exactly fit for entertaining at present,’ he said.

He didn’t seem arrogant at all. In fact, the way he was looking at me, with the sun catching in his eyes like that (those gorgeous eyes, flecked with hazel — the eyes that had met mine that cringe-making morning in Sainsbury’s) — he seemed almost shy. I glanced through the open door. Poor guy. The place was totally trashed. It stank of sour spilled beer and cigarette smoke. It would take him forever to clean up.

‘You had quite a party last night,’ I said.

‘Yeah well, you should’ve come over.’

‘You should’ve asked me.’

‘I would have,’ he said. ‘But I didn’t think it would be quite your scene.’

There it was. He’d practically spelt it out. He thought I was just a kid and nowhere near old or cool enough to party with his friends. It wasn’t surprising — he’d only seen me in school uniform. Or going to see a kids’ film — it was so unfair. But I’d show him. Just give me time.

‘Look, I’d better be going,’ I said.

But he didn’t seem to want me to go. He was being really friendly for some reason.

‘Don’t go for a minute. You live at number twenty-two don’t you?’

I nodded.

‘Name’s Matt,’ he said, holding out a hand.

We stood in that totally trashed garden and shook hands really formally. Like some funny old-fashioned couple. I liked the feel of his hand, liked it too much. I mean, he had a girlfriend for God’s sake — I’d seen them getting off together.

I mumbled my name and then there was a ghastly pause. I stood there feeling awkward.

‘Who is it who that plays a … clarinet, is it?’

‘Oboe.’ I felt myself flush scarlet. He must have heard me practising. This was just so galling. Now he thought I was a nerd as well.

At that moment I heard Dad’s voice calling me. ‘Natasha!’

‘I’ve got to get back, for breakfast …’ I said.

‘Don’t go yet.’

‘Look, I’ve got to.’

‘Think the old bastard will leave those birds alone now?’

I shrugged. ‘I don’t know.’

‘Tasha? Did you hear me?’ Dad was standing at the side gate of number twenty-five — frowning.

‘Looks like you really had better go,’ said Matt.

‘Yeah, OK. Bye.’

I made my way back across the road as fast as I could.

I stormed through the front door with Dad hot on my heels.

‘I just can’t believe you did that …’

Dad looked unrepentant. ‘Did what?’

‘Humiliated me, in front of that guy.’

‘I beg your pardon. I did nothing to humiliate you.’

‘Treating me like a child like that.’

‘I merely pointed out it was breakfast time.’

‘You know very well what I mean.’

Mum and Dad ganged up on me after that. They made a real scene over breakfast.

‘I just don’t believe it,’ Mum was saying. ‘After last night. God knows what those people were on …’

‘And there you were standing talking to the bloke — after I expressly asked you to keep away,’ added Dad.

‘Keep away. What do you think he is — an axe-murderer? You’re mad. If you actually bothered to speak to him you’d find out — he’s really nice …’

‘He doesn’t have very nice friends,’ Mum pointed out.

‘How can you tell?’

‘Certain things I found in the flower bed, when I emptied the rubbish this morning.’

‘I reckon those people were gatecrashers. Let’s face it — they didn’t do any real damage …’

‘What about Mr Levington’s wall?’

‘Mr Levington deserved it. He is a fascist — do you know what he was doing this morning?’

‘Apparently that boy was being really abusive to him.’

‘He rang us up in a real state,’ said Mum.

‘I’ll tell you what he was doing — trying to knock down the house-martins’ nest. And there are baby birds in it.’

‘That’s awful. Dad, you’ve got to do something,’ said Gemma

‘He wasn’t, was he?’ asked Dad.

‘Yes he was. That’s how I got talking to Matt — that’s his name. He was trying to stop Mr Levington too.’

Mum and Dad exchanged glances.

‘So that’s what old Levington was going on about,’ said Mum.

‘I’ll go and have a word with him,’ said Dad.

When Dad came back we were all waiting expectantly.

‘Well, I put the fear of God into Levington. Said they were protected and I’d report him to the RSPB.’

‘Are they?’ asked Mum.

‘Don’t know. But if they’re not they should be. Think it did the trick though. Don’t think he’ll be touching that nest again. But he’s been on to the police about our squatter. Seems to think after last night, it shouldn’t be too much of a problem to get him evicted.’

Gemma’s gaze met mine. I sent her a silencing frown.

Chapter Ten

Dad took us on one of our London-wide cycle tours that Sunday. We were meant to be checking the cycle paths along the Thames to Richmond and back again, so we were out all day.

I was at my least enthusiastic. I hadn’t had that much sleep the night before and cycling was the last thing I felt like. I do have a life of my own actually, in spite of all appearances to the contrary. And I wouldn’t have minded keeping an eye on what was going on across the road. As far as I knew, a load of council bailiffs were breaking into number twenty-five and Matt was being forcibly evicted. I kept going over and over in my mind the events of the last twenty four hours. Each time I ended on — and lingered over — our meeting earlier that morning.

Dad kept on stopping and noting things down about the state of the paths on his Psion and I was supposed to be keeping my eye on the number and frequency of cycle-path signs. I had a pad fixed to my handlebars and a pen on a string — God, I must have looked naff. It had rained during the night and a splattering of mud up my legs added the finishing touch to my appearance.

As our bikes sloshed through the puddles, I was deep into a soul-searching examination of the conversation I’d had with Matt. I know it hadn’t been much but I could remember each and every word. He’d been really nice about the house-martins — but maybe he was just getting his own back at Mr Levington. I went hot and cold, recalling things I’d said. Adding everything up, I’d probably come across as some lost, sad oboe-playing birdwatcher. Or worse — a pathetic school kid with an obsessively protective Dad …

‘Missed one,’ said Dad, as we rode under the shadow of Hammersmith Bridge. He came to a stop standing on his pedals, idling his bike.

I took out my pencil and stabbed at the pad. I was feeling hot and cross and my cycle helmet was driving me mad.

‘What’s up, Tash?’ asked Dad.

‘I didn’t ask to come.’

‘Sunday cycle rides are meant to be a treat. I’ve made a really special picnic,’ said Mum.

‘Oh great, yum-mee,’ I said in a really flat voice. I know I was being a pain. Gemma and Jamie were riding on ahead making whoops and screams that echoed under the bridge. I guess it was a big treat — for them.

Mum frowned at Dad. But Dad just swung his bike round and started after them.

We cycled on past the smelly bit where the sewage farm butts up to the towpath. Gem and Jamie were making their usual exaggerated ‘I’m-going-to-be-sick’ noises. But I just pedalled on stoically. It was a crummy day, I felt like death warmed up and the delightful smell of sewage really topped the lot.

It rained throughout our picnic at Ham House. We all clustered together under a tree but the rain still got through and the crusty loaf Mum had bought went disgusting and soggy. The rain really set in after lunch so we had to put on our gross waterproof kagouls. We rode home as fast as we could. I had my hood on underneath my helmet. I must’ve looked as though I belonged to some strange cult. My fringe was sticking to my forehead in flat spikes and my face felt red and hot. That’s the thing about rainwear — it doesn’t let the rain in but it doesn’t let anything out either. By the time we reached Frensham Avenue it felt like a tropical rainforest inside mine. I steamed up to the house just praying that Matt wasn’t looking out of his window at that precise moment.

I made a bee-line for the bathroom before anyone else could get in there. Then I ran a deep hot bath with bubble bath in and ignored Jamie and Gemma beating on the bathroom door. Eventually Mum joined in.

‘Rosie’s here to see you. Hurry up and leave the water in — they can go in after you.’

‘Honestly,’ I shouted back. ‘Anyone would think we were living in the Third World!’

‘What’s that about the Third World?’ It was Rosie’s voice. She was standing outside the bathroom waiting for me.

I climbed out of the bath and put on my towelling robe.

‘Re-using bathwater. Its Mum’s bid to save the world from drought and disaster,’ I said.

I could hear Jamie through the bathroom door. ‘Did you know we’ve got a hippo in our lavatory?’ he said importantly.

‘Really!’ said Rosie, pretending to sound amazed. ‘How horrid. Why doesn’t it try to climb out?’

‘It’s in the top bit. There’s a lid on.’

‘All the same. It can’t be very nice in there.’

‘It’s not a real hippo, silly,’ said Jamie.

‘Isn’t it?’ said Rosie.

‘Come on,’ I said. I’d been talking to little kids all day. I’d had enough of it.

‘So?’ said Rosie when we were alone in my room.

‘I actually got to speak to him, properly, this morning.’

‘You did! What’s he like?’

‘He’s not nearly as full of himself as we thought.’

I gave her a quick update on the events of the morning and then the night before, complete with an account of the party in lurid detail. But she only seemed interested in one thing — Matt.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книгиВсего 10 форматов