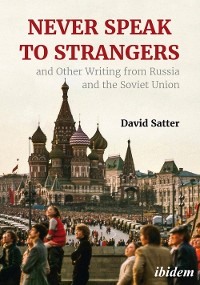

Never Speak to Strangers and Other Writing from Russia and the Soviet Union

Now, however, with the heavy industry base created, the need for efficiency is paramount because the economy faces an exhaustion of inputs. Oil production will increase only 2 per cent this year and may soon begin to fall. Population growth has levelled off, particularly in the European areas where industrial labour is most badly needed and the area of arable land is expected to decline.

Achieving efficiency would appear to require some measure of liberalisation and decentralisation, with the introduction of qualitative measures of economic performance and greater autonomy for factory managers. This was tried at the time of the Kosygin reform in 1965, but had little practical effect. There is now little likelihood that the Soviet economy will be decentralised, and it is no accident that Mr. Brezhnev failed to mention this as a possibility.

Allowing individual factory managers greater freedom to make economic decisions on economic grounds would not have direct political consequences. But the element of economic democracy represented by local decision-making would indirectly create greater possibilities for political democracy because economic discussion inevitably touches on questions of policy.

Under the Soviet system the State, which is ruled by the Party, must have full authority in all areas including the economy. Even the seemingly innocuous decentralisation of economic decision-making would weaken the authority of the Central Government.

This is why, despite Mr. Brezhnev’s threat to replace officials who fail to meet their targets, the decline of the Soviet economy is likely to continue throughout the next decade, leading to ideological vulnerability and public discontent, and giving the authorities an object lesson in the limits of centralised power.

Financial Times, Friday, December 21, 1979

Josef Stalin’s Legacy Leaves

Soviet Leaders in Dilemma

Each member of the older generation will be left with his own memories, but no official celebration is planned today for the 100th anniversary of the birth of Josef Stalin and few people are expected at the Kremlin Wall to lay flowers at the former dictator’s grave.

Josef Vissarionovich Djugashvili, the man known as Stalin, literally “man of steel” created the modern Soviet state. But the Soviet authorities show little inclination either to glorify or condemn him. Sometimes it seems that they would prefer most of all to forget him.

The dilemma posed by Stalin springs from the fact that he turned the Soviet Union into a totalitarian state. Though the present leaders may want to disassociate themselves from his crimes, they continue to exercise absolute power through the structure he created.

Kommunist, the Communist Party’s theoretical journal, tried to draw a distinction this week between Stalin and the Soviet system. The journal said Stalin’s career had both positive and negative sides but that the “negative phenomena,” namely “Stalin’s crude abuses of power,” did not reflect the nature of the Soviet system, only the distortions of the “personality cult.”

The only serious Soviet attempt to come to terms with the consequences of Stalin’s rule was made by Nikita Khrushchev, the former Soviet premier who authorised publication of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

Between 1962 and 1964 there was a sharp increase in historical and sociological research into the Stalin period. But when Khrushchev was removed, at the October 1964 plenum, this research and the publication of literature about Stalin came to an end.

There is now a basic lack of comprehension about Stalin in the Soviet Union, both on the part of ordinary people who remember how soldiers threw themselves under tanks shouting “For country, for Stalin, for mother,” and on the part of Soviet officials who, anxious for respectability, prefer not to dwell on how the regime was established.

By today’s standards, the first years of Soviet power under Lenin were open and democratic. Lenin used terror but he operated on the Marxist assumption that the need for repressive measures was temporary. The Press wrote frankly about famine and disasters, and there was intensive intra-party debate. Censorship was comparatively lax. Even the memoirs of White Army generals were officially published.

Stalin put his imprint on the Soviet State by effectively gathering all power into his own hands and then, through mass indiscriminate terror, putting an end to the diversity Lenin had tolerated. Stalin put to death 90 per cent of the members of the 1934 Central Committee during the purges of 1937 and 1938 and also most of the staff personnel who worked in the Central Party apparatus.

When Aldo Moro, the Italian Christian Democratic leader, was kidnapped by the Red Brigades last year, the Soviet Press expressed its outrage that the Red Brigades might be associated in some people’s minds with the Soviet Union. In fact no imagined regime run by the Brigades could prove more pitiless than the regime actually established by Stalin.

If total fear deprives people of human qualities and turns them into examples of the animal species Man then it was no accident that in 1937, when the terror reached its apex, a foreign resident found that Russians she approached on the streets “scattered like mice.”

The surrealism of Soviet political life, in which everything accomplished through compulsion is said to be voluntary and a population which dare not speak out is depicted as unanimous behind the Party’s policies, reflects a tradition established by Stalin. While secretly sending millions to their deaths, he spoke publicly of the need to be responsive to the wishes of the people and to treat individuals with the tenderness a gardener shows to a delicate plant.

There will never be a precise figure for the number of blameless persons sent to their deaths by Stalin. No family was untouched, and the figure of 20m cited by Western historians may be realistic.

The regime Stalin created made it possible for a single man whose outstanding characteristics were deviousness and crudity to bring an entire country to its knees. The Soviet Union after 1930 gave the impression of a land of total unanimity in which Stalin’s wishes were law. Stalin chose to eliminate even the possibility of opposition and elements of the realm he created are clearly visible in Soviet life today.

The Soviet political system concentrates power today as effectively as it did in Stalin’s day. The last policy debate inside the party occurred under Stalin, in 1929. It was on collectivisation and Nikolai Bukharin, the Politburo member who argued for a moderate approach, was tried nine years later as a German spy and shot.

The present Politburo meets in secret; 26 years after Stalin’s death, there has not been a single case of a policy being debated in the lower party ranks. Even when Khrushchev was removed from power in 1964 and the charges against him were read out at local party meetings, people were not allowed to discuss the charges but only to ask questions. The notion of the party as the all-powerful instrument of a ruler or ruling elite comes from Stalin.

Stalin both realised Marxist ideology and discarded it, and this pattern too has become characteristic of the Soviet State. The development of the Soviet Union’s “productive forces” predicted by Marx did not happen of its own accord, so he strengthened the repressive power of the State, which—also according to Marx—was supposed to fade away. He then pretended the repression did not exist.

Stalin greatly intensified the system of censorship established by Lenin and sought through it to control all published or broadcast information. He wanted to eliminate any research which directly or indirectly cast doubt on the value of the Soviet system and he wanted all art to reflect his personal taste.

Today this system has been liberalised. Foreign radio broadcasts are no longer jammed. Some previously banned poets, such as Mandelstam, Tsvetayeva and Akhmatova, are now published in limited form. Information remains curbed but the goal now is not to programme individuals but simply to make it impossible for the average citizen to form a coherent view of the outside world.

Stalin also affected the structure of Soviet ambition. The old Bolsheviks who were shot in 1937–38 were replaced by cadres completely loyal to him personally. Each of the old Bolsheviks had a long political biography, but the young men promoted rapidly to take their places had little political experience and were in no position to gain any under the conditions of terror. Their satisfaction came from career advancement; and Soviet careerism has proved as apolitical and ideologically indifferent as any in the West.

In the final analysis, perhaps the most important and the most ominous aspect of Stalin’s legacy is that he chose to fall back on the Russian tradition of progress through terror and force. Stalin’s apologists, both in Russia and the West, frequently refer to the difficult conditions he faced and the tangible gains the Soviet Union achieved. These calculations fail to consider the fact that Stalin set a pattern which may claim victims for many generations to come.

Stalin’s rule left behind political passivity, because Soviet citizens came to take it for granted that all major decisions would be taken without their participation. It also left behind an abiding fear of the state machine on which the present Government freely draws.

Soviet leaders now want stability. After Stalin’s death they took a number of steps to dismantle the terror apparatus he set up. The KGB, which was a parallel system for arresting, trying, and killing those thought guilty of political crimes, was reduced to an investigative body which must turn over its information to the prosecutors and the courts. Several KGB functions were given to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and both the KGB and Ministry were put under the control of the Party.

It is too soon to say whether these changes will forestall a new wave of terror. The Soviet form of government is a centralised, one-party system with extraordinary government powers. If opposition arises, there is a built-in tendency to eliminate it. At the same time the torpor of Russian life too often shows that a nation accustomed to being bullied can lose the ability to act on its own.

There is likely to be no honest attempt to understand Stalin in the Soviet Union. The silence may be convenient but it is far from neutral, because against the reality of state achievements it implicitly supports the notion that the interests of the state justify any human cost.

The tragedy of the Stalin era is that once again Russian leadership was cast in the mould of Peter the Great and Ivan the Terrible, reinforcing the worst aspects of the Russian state tradition at the very moment when the legatees of serfdom were seeking a new way forward.

Financial Times, Wednesday, January 23, 1980

Sakharov’s Arrest Links

Dissidence with Detente

The arrest of Dr. Andrei Sakharov1 shows that the Soviet Union is prepared to add a cynical linkage principle of its own to the East-West struggle to define the terms of detente.

Soviet authorities have stressed that Moscow has no intention of retaliating against the United States for the grain embargo or the proposal to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics. But the arrest and exile of Dr. Sakharov cannot be understood as anything but a direct reflection of the present conflict between the two super-powers.

The Soviet Union depicts itself as the victim of US punitive measures but, as the seizure of Dr. Sakharov shows, a decision has been taken at the highest level to strike back at the US. This will be done not through diplomatic action but through retaliation against the Soviet Union’s own citizens.

The USSR has consistently rejected any linkage between detente era agreements and Soviet military expansion in the Third World, but for several years it has tacitly agreed to the linkage between detente’s advantages and its treatment of its own people.

Dr. Sakharov, more than any other Soviet citizen, has represented opposition to totalitarianism and the desire of some Soviet citizens for democratic freedoms. There have been Press campaigns against him and he has been warned by state prosecutors that he was “abusing their patience.” But the Soviet desire for international acceptance always prevented his arrest.

In early 1977, the KGB began an unprecedentedly thorough crackdown on dissent which included the almost complete suppression of the various dissident groups which were formed to monitor the Soviet Union’s observance of the Helsinki Accords. But Dr. Sakharov remained untouched.

This was important because, by his very presence, Dr. Sakharov afforded a measure of protection to all other Soviet dissidents. They benefited from the fact that his international stature as a scientist and recipient of the highest Soviet academic honours leant status to the dissident movement as a whole.

Dr. Sakharov’s position came to symbolise the Soviet reluctance to offend the West. But now that the international situation has changed dramatically and U.S.-Soviet relations have sunk to their lowest point since the Cold War, Dr. Sakharov has been seized. He has been sent into what may be permanent exile in a city where no foreigner can reach him, and where he will be remote from his friends.

With Dr. Sakharov removed from Moscow, the Soviet authorities will have all but achieved their goal of eliminating active dissent. The past three months, which have witnessed a steady deterioration in U.S.-Soviet relations, have also been marked by over 40 arrests including those, of Tatyana Velikanova, who helped put out the “Chronicle of Current Events,” Father Dmitri Dudko and Father Gleb Yakunin, two dissenting orthodox priests, and Antanas Terleckas, a Lithuanian nationalist.

It is unlikely the authorities will stop with the latest arrests. The dissidents commanded the sympathy, if not the active support, of a significant part of the Soviet intelligentsia. With almost all of the active dissidents in prison or in exile, the Soviet authorities are free to bring greater pressure on intellectual and cultural figures or citizens who simply fail to conform.

The “decent opinion of mankind” played a vital role in Soviet internal political life, because the system does not set its own limits. In many cases it has seemed that the Soviet Union took an action specifically to provoke a Western response because it was powerless to make value judgments on its own.

Soviet acceptance of “foreign interference” in its internal affairs was made explicit last year, when Moscow bargained with Washington for two convicted spies by releasing five of its own political prisoners. It thereby confirmed the right of the U.S. to interest itself in the fate of Soviet citizens on general humanitarian grounds even if the persons involved had no connection with the U.S.

The USSR allowed Jewish emigration in 1979 to increase to 50,000 a year in an effort to gain most favoured nation trade status from the U.S.

The action against Dr. Sakharov, however, shows that the authority’s readiness to bargain Soviet internal liberty for Western concessions also has ominous connotations. If relations suffered, entire sections of the population could be held hostage.

Now, with detente faltering, Moscow has acted against Dr. Sakharov who symbolised the hope for greater freedom. Without the extra protection to others which his presence in Moscow afforded, the Kremlin will find little to restrain it if it decides to intensify repression to levels not seen in many years as the particular Soviet response to the chance pattern of foreign events.

1 Dr. Sakharov was arrested in Moscow on January 22, 1980 and exiled to the Volga River city of Gorky (now Nizhnii Novgorod).

Financial Times, Friday, January 25, 1980

The Limits of Detente

The progress of detente has always been based on some necessary illusions. With the invasion of Afghanistan and the exile of Dr. Andrei Sakharov, the Nobel Peace Prize winner and leader of the Soviet human rights movement, they are being dispelled all at once.

The Soviets want detente for political, economic and psychological reasons. Disarmament reduces arms expenditures and trade brings access to western goods. Cultural, technological and sporting exchanges earn the respectability which comes of co-operation with the rest of the world. But the Soviets, because of the ideological nature of their society, have no political goal—including detente—which transcends their commitment to expanding their own power. They have insisted from the beginning that Soviet military intervention in the Third World and the final say on how they treat their own people are no concern of anyone else.

Recent events have seemed to be dominated by a sinister automatism. The invasion of Afghanistan expanded at a stroke the area of the Soviet military bloc, but it also prompted U.S. grain and technology embargoes and President Carter’s intention to boycott the Olympic Games in Moscow.

Soviet officials answered the U.S. moves not by taking economic and political steps against the U.S., but by exiling Dr. Sakharov.

While it lasted, the freedom of Dr. Sakharov, who symbolised resistance to totalitarianism, epitomised the Soviet authorities’ desire to appear less repressive and to preserve elements of trust and mutual comprehension essential to the development of East-West relations. His forcible removal from Moscow signals a new attitude towards dissent and towards the opinion of the outside world.

Relations between the Soviet Union and the U.S. have now sunk to their lowest level since the Cold War, and the speed with which the fabric of relations has come unravelled reflects the diametric opposition of the Soviet and American conceptions of detente, which could only be ignored, but not reconciled.

The U.S., guided by Dr. Henry Kissinger, the former Secretary of State, sought to restrain Soviet behaviour by creating a web of mutually beneficial relations that the Soviets would be unwilling to risk by adventures in the Third World or by the kind of mistreatment of their own citizens that would attract unfavourable attention in the West.

The Soviets saw detente more narrowly, as a means of reducing military tension with the West to enable them to meet the threat from China and to gain western technology. They assumed it would be possible to continue to expand militarily in the third world and that the fate of the Soviet human rights movement, however much it might exercise western public opinion, would not affect their relations with western governments.

The incompatibility of the two viewpoints became obvious at the latest with the invasion of Afghanistan. But the Soviets mounted their first overt challenge to detente, as the U.S. understood it, in 1975, three years after President Nixon had gone to Moscow to sign the first Strategic Arms Limitation Agreement, SALT 1, and the major agreements on scientific and cultural exchanges and trade. Soviet advisers and Cuban troops intervened in the Angolan civil war and assured the victory of the MPLA faction of Mr. Agostinho Neto. The angry public reaction in the U.S. to the intervention was an important reason why the SALT 2 negotiations were put off for more than a year.

Flexibility

The Soviets did show some flexibility on human rights. They avoided arresting prominent dissidents and allowed others to be exchanged. They did renounce the 1974 Trade Act when amendments made to it in the U.S. Congress tied trade advantages to explicit assurances that Jews would be allowed to leave the country. But Jewish emigration, after a temporary drop, began to increase to record levels a short time later. Soviet officials made a quiet effort to use this fact to get the amendments removed.

When President Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, the SALT 2 negotiations were resumed, but the reaction to the Angolan intervention did nothing to dissuade the Soviets, using the Cubans as their proxies, from mounting another military operation in Ethiopia early in 1978. Soviet advisers, $1bn worth of Soviet weapons and 17,000 Cuban soldiers helped the regime of Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam defeat an invasion from neighbouring Somalia. In 1978, Vietnam, a close ally of Moscow’s, invaded Kampuchea and replaced the Pol Pot regime with the Vietnamese puppet government of Heng Samrin.

It was against this background that the Afghanistan crisis which threatens to take U.S.-Soviet relations back to the Cold War emerged. The Soviets were faced with a deteriorating situation in Afghanistan where a pro-Soviet Government, installed by a coup in 1978, appeared in danger of being overthrown by anti-Soviet Muslim guerrillas.

The Soviets paid no political price for their intervention in Angola and Ethiopia. But they cannot have been under any doubt that there would be a sharp American reaction if they flouted the U.S. notion of detente by intervening openly in Afghanistan.

Detente created greater security in Europe, but only on the condition that the Soviets did not go too far through open military intervention in tipping the balance of forces in the Third World. The U.S. had little choice but to link detente agreements to Soviet behaviour in the Third World because the Soviet Union has several inherent advantages there. No public outcry within the Soviet Union will prevent the dispatch of Soviet or Cuban troops to a zone of conflict. Once a Soviet-style regime has been installed in another country, the Soviets work to ensure that it will never be displaced.

When the Soviets decided to go into Afghanistan they had reason to be worried about the strategic situation on their southern border. Soviet officials saw little prospectfor good relations with Iran’s religious leaders in the long run, in spite of present U.S.-Iranian conflicts. All attempts to improve relations with China had been rejected as China moved steadily closer to the U.S.

Soviet officials have said that when the Soviet Union went into Afghanistan they believed that they had very little to lose because of the failure of the U.S. Senate to ratify SALT-2, the NATO decision to deploy new medium range missiles in western Europe, the increase of U.S. and NATO defence spending, and the long standing U.S. failure to respond to Soviet “signals” asking for broader trade opportunities.

All this is probably true. But there is little possibility that the Soviet Union would have desisted from invading Afghanistan had the survival of a Marxist regime there depended on it, no matter what the state of detente. The goodwill of the detente era carried within it the risk that people in West, who value the benefits of East-West cooperation, would lose their sense of realism. Even President Carter was affected by this.

Hierarchical

The Soviet Union, although an established power, differs fundamentally from most other states. It is organised like a revolutionary movement with the hierarchy, discipline and secrecy of the pre-revolutionary Bolshevik Party.

The idea of the Soviet Union as the vanguard of a committed ideological movement is false if measured against the Soviet people’s true beliefs and could almost be abandoned were it not frozen into the power structure of Soviet society with its lack of liberty, hierarchical gradations of authority and privilege, and proliferation of “secret” establishment; which do not guard anything that would be considered secret in any other society. But being organised like an ideological movement, it feels compelled to act like one.