0

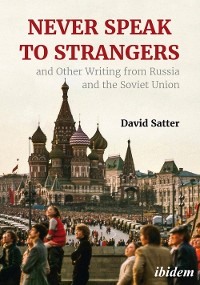

0Never Speak to Strangers and Other Writing from Russia and the Soviet Union

Afghanistan’s Rocky Road to Socialism

In the crowded bazaars of Kabul’s old city, life proceeds at a pace set centuries ago. Craftsmen hone their fine copper, and brass merchants in shallow stalls idly sip tea while veiled women inspect meat carcasses amid swarms of flies.

In a city of 700,000 where many pray five times a day but which has no municipal sewage system, the activities of the middle ages linger on. Itinerant barbers cut their customers’ hair on patches of earth and scribes compose letters for men in flowing robes.

The cities and baked mud villages of Afghanistan have seen little change for centuries but the country now appears on the brink of one of the most important attempts at modernisation in its history and, possibly, it could bring with it unprecedented bloodshed.

The regime which seized power six months ago in a coup has moved the country appreciably deeper into the Soviet orbit and has pledged itself to abolish feudalism. Mr. Hafizullah Amin, the foreign minister and apparent strongman in the Government, said the goal of the ruling Khalq (People’s) party is to create a modern, Socialist society.

The party is conducting an intensive drive to recruit young men in every village and productive unit in the country at the same time as making many arrests, particularly in the armed forces, and suppressing Islamic revolts in the eastern provinces of Badakhshan, Kunar, Paktia, Logar, and Laghman.

Russians have become the most common foreigners passing through Kabul airport and are now a common sight in Kabul in the crowds behind the Pul-I-Kheshti mosque or strolling past the rug emporiums on Chicken Street under the eyes of suspicious merchants.

The anomaly of a socialist government in a fundamentally conservative, deeply religious country like Afghanistan has not been lost on either the Government or its many actual and potential opponents. Government representatives are being assassinated in the provinces by the Akhwani, the semi-secret Moslem brotherhood and there have been mass desertions from the armed forces and the beginnings of guerrilla activity.

The best estimate of the Khalq Party’s present strength is that it numbers no more than 2,000 hard core members. For purposes of comparison, there are believed to be more than twice that many people under arrest and awaiting an uncertain fate at the Pul-e-Charki prison outside Kabul.

Russian Backers

This small, organised group and its Russian backers want to remake this country where the terraced mud and adobe houses rise mirage-like atop each other in clouds of mist and dust on the sides of barren hills and the devout pray on prayermats in the corners of public buildings. To do this, however, they may have to use great violence which the regime is now in no position to apply.

The coup itself is believed to have involved only 600 officers commanding two divisions and an armoured brigade. Loyal units were prevented from coming to the relief of the regime by the air force, under the command of Major General Abdul Qader, a member of the Parcham (flag) Party—rivals of the Khalqists since Afghan Marxist-Leninists factionalised in the 1960s.

As against this, however, the Khalq Government—which, is headed by President Noor Mohammed Tarakki, a poet, ex-shipping clerk, and former Press attaché in the Afghan Embassy in Washington—can count on the support of 2,000 Soviet military advisers and 3,000 Soviet civilian advisers, in all, four times as many Soviet advisers as before the coup.

The regime’s ultimate intentions are far from clear. Government meetings are opened with readings from the Koran in an attempt to still Moslem fears but the actions the regime has taken in promulgating, although not implementing, a policy of dividing up the estates of large landowners, and abolishing smallholders’ debts to money lenders, give an indication of the Socialist direction in which they intend to proceed.

The increasing Soviet presence in Afghanistan and the new regime’s dependence on Soviet support have caused alarm in the West. This is belated in light of the fact that social and political conditions created years ago made it a virtual certainty that any modernising government would inevitably be Soviet oriented.

With 60 per cent of the population of 17 m seeking out a living as farmers, an ossified social structure and mass illiteracy, the voluntary processes of a market economy have long seemed to many educated Afghans to have little to offer.

Soviet influence was first established in the 1950s when the Russians agreed to supply Afghanistan with arms after the U.S. turned down Afghan requests for arms in connection with the border dispute with Pakistan. Young Afghan officers thereafter spent up to seven years training in the USSR. Many returned to join the Khalq or Parcham parties.

In the last 20 to 25 years, Soviet assistance has totalled $1.5 bn—more than that provided by any other country. The impact of this was to bring Soviet advisers into the ministries, particularly of planning and mines and industries. A Soviet model of development based on industrialisation is accepted by the Government—as it was by the former regime of President Mohammed Daoud—as the most valid approach for Afghanistan’s future development.

Under the Daoud Government, the situation in Afghanistan, however, was one of complete stagnation. In a country where half the children die before the age of five, the Daoud regime had no stated commitment to development.

A member of the Mohammad Zai clan, which had ruled Afghanistan for 200 years, Mr. Daoud did not make use of a Soviet credit line worth $308m. The smallest Western aid proposals were debated at Cabinet level where weeks were lost in arguments over the wording of agreements. In April of this year, Mir Akhbar Khaibar, a leading Parcham ideologist, was assassinated by unknown persons. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people took part in the funeral and a demonstration at U.S. Embassy, frightened the Daoud Cabinet and led to the arrests of Mr. Tarakki and Mr. Amin, the organisers of Khalq support in the armed forces. On April 27, a Cabinet meeting was called to consider purges in the armed forces. This triggered the coup.

The coup has been described as “desperate, daring and do or die”—it was violent, involving heavy fighting and hundreds of deaths, including those of Mr. Daoud and his family, and its outcome was uncertain all through the night of the 27th. Its success was followed by waves of arrests in the armed forces and a purge of the civil service.

As soon as the new Government had organised itself, however, the Khalqists began the elimination of their Parchamist partners in the coup starting with the dispatch of Mr. Babrak Karmal, former leader of the Parcham, and four other Parchamists to ambassadorial posts and their subsequent dismissal. This was followed by the arrest of Gen. Qader.

The purge of Parcham leaders was followed by the arrests of rank and file Parchamists in the armed forces and a second purge of the civil service.

These measures secured a Khalq monopoly of power but whittled down the regime’s base still further. Public lectures, rallies in military units and factories, and the requirement of Khalq membership for important posts are all now being used to swell the party’s ranks.

The purges appear to be over for the time being and there are signs that the new Government is growing in self-confidence. The Khalq Party still declines to refer to itself as “Marxist-Leninist” for fear of posing too sharply the conflict with Islam but two weeks ago, the regime introduced the new Afghan flag, which is entirely red and no longer sports the traditional Islamic colour of green.

Still, the Government is taking no chances. There are 60 tanks inside the palace grounds as a precaution against a counter coup, and an 11 pm curfew is strictly enforced while powerful searchlights nightly sweep Kabul’s surrounding hills. Military units are constantly being shuffled, the command structure is shattered and the air force is grounded.

If the regime consolidates itself, it must decide how far to go in transforming Afghanistan society. The five-year plan now being prepared is intended to introduce the first serious industrialisation in the country’s history.

The intention is for the share of industry to increase with each subsequent five-year plan. Agriculture is to be collectivised on a voluntary basis following land reform. Private enterprise, is eventually to be abolished, and the 10 per cent of the population which is nomadic is to be offered land for voluntary resettlement.

Agriculture

Western experts view this programme with distrust. They believe Afghanistan cannot be competitive as an industrial society and have urged diversification of agriculture with concentration on cash crops such as cotton, nuts and dried and fresh fruit.

In keeping with national pride and the regime’s “antiimperialist” bias, the Afghans have rejected this advice and although dependent on outside sources for an estimated 70 per cent of the funds for their five-year plan—most from the Eastern Bloc—they are going ahead with capital intensive projects such as exploitation of the Ainak copper deposits. This will isolate them from the world economy and tie them irrevocably to the Soviet Union.

The effective date of the decree on land reform has been postponed until next autumn—in effect, for two more harvests—and the article abolishing peasants’ debts to money lenders is, in many cases, being ignored by peasants who are paying their debts lest they be deprived of credit to get seed for next year’s planting.

There seems little doubt, however, that if the regime wants to make rapid progress in industrialisation and collectivisation it will at some point have to decide whether to use overwhelming force to achieve its ends.

There is another worldly quality to this remote, mountainous country where life seems to centre on prayer, the local tearooms, which are full of animated Afghans at the height of the working day, and the campfires of tribal nomads, which dot the side of the main highway to the capital at night. The reaction to an attempt to destroy the traditional patriarchal society by Marxist-Leninist ideology would probably throw the country into chaos.

There is however some backing in Afghanistan for forcible methods.

If the Khalqi regime emerges as militantly revolutionary, its activities could also have an international dimension. The regime could inspire increased violence in Pakistan and Iran by giving support, at the Soviet Union’s behest to the left-wing separatist movement, acting on behalf of 5 m Baluchi tribesmen.

If the Baluchis, using Afghanistan as a staging area, are successful in separating Baluchistan from Pakistan—and there are many who believe that in the medium term they will make the attempt—Afghan militancy would have helped destabilise the regional balance, allowing the Soviets, at long last, to realise the long-held aspiration of dominating Afghanistan and Baluchistan, thus achieving a warm water port—Gwadar—on the Arabian sea.

Financial Times, Wednesday, March 8, 1978

David Satter visits Murmansk, the USSR’s Arctic metropolis

Russia’s ‘Civilised North’

The low-lying Arctic sun burns through the white mist for only a few hours in midwinter as Murmansk, the world’s largest city north of the Arctic Circle, emerges from the total darkness of three months of polar nights.

Beyond the pillared stone buildings on Lenin Prospekt, the city’s main street, the railway yards and massive harbour, with its steam-shrouded cranes and ocean-going ships, testify to the accident of geography which is the city’s raison d’être.

Although 69 degrees north, Murmansk has the only ice-free port in North European Russia at the eastern end of the Gulf, Stream. The city has become, perforce, a social laboratory for testing man’s ability to thrive in arctic conditions.

Murmansk is 1,000 miles north-west of Moscow at the top of the sparsely populated Kola Peninsula. There are no nearby cities of any consequence and, with little in the way of cultural facilities, Murmansk is one of the most isolated cities of its size in the Soviet Union.

The most difficult adjustment for Murmansk’s new residents, however, is getting used to three months of total darkness between mid-October and mid-January. This is followed by a three month period in the summer when there is no darkness at all.

Under these conditions, Murmansk could have the same difficulty holding population as new cities in remote areas of Siberia. But although 5,000 to 6,000 persons leave Murmansk every year, the city’s population has grown by 8,000 a year since 1959. This is a tribute to the complex of economic, health and recreational measures designed to keep it functioning.

Murmansk is what its residents call the “civilised north” to distinguish it from cities in Siberia where conditions are primitive. There is a housing shortage in Murmansk, as elsewhere in the Soviet Union, and many live in communal flats.

But the housing stock is modern and with 400,000 inhabitants, Murmansk boasts the largest library and the only trolleybus service north of the Arctic Circle.

This winter in Murmansk has been one of the worst in memory with temperatures hovering around −30 centigrade. For the first time in 13 years, passenger ship transport to the port, a major transit point for Soviet goods shipments, actually stopped on February 14.

Despite difficulties, however, the port, which was the destination of Allied convoys during the Second World War, was soon operating again and this reliability in a country largely frozen in winter is what has made Murmansk an essential urban centre.

The impressive harbour is used extensively by the Soviet northern fishing fleet, which is serviced by Sevryba, the Soviet Union’s largest fish processing combine. Although the catch from the Barents Sea is declining after years of over-fishing, Murmansk remains one of the Soviet Union’s biggest fish centres.

The Soviet naval presence is even more important but less obvious. The northern fleet in Murmansk and the nearby submarine base of Severomorsk constitutes the greatest concentration of naval military power in the world. Western intelligence places the strength of the northern fleet at 51 surface ships and 126 submarines, of which 54 are nuclear powered.

The use by commercial and military shipping of the fiord like Kola Bay is so intensive that there is no place on the bay set aside for recreational purposes. It is this concentration of activity, carried on for months in sub-zero cold and often in conditions of total darkness, which is made possible ultimately by the social measures to maintain Murmansk in a desolate area where snow falls 10 months out of the year and trees only reach sapling size after 65 years.

The most important incentive to work in Murmansk is economic. On arrival, a worker receives a 40 per cent pay increase raised at six months’ intervals by 10 per cent, until, after four years, he is earning at least 200 per cent of what he would have earned at a job farther south.

The number of people employed in the fishing industry is expected to decrease with technological improvement and the declining catch in northern waters. Plans call for the development of light industry, including knitted ware, manufacturing and the opening of a vodka factory to save the cost of transporting bottles 900 miles up the railway line.

The goal of holding population in the far north would probably not be achieved, however, were it not also for Murmansk’s comprehensive health care system. The long Polar night and a period in February and March when the sun shines but gives off no ultra-violet rays can cause severe vitamin deficiencies. These are warded off by ultraviolet lights in factories and schools and daily vitamin doses for every Murmansk resident at “health points.”

In the summer, Murmansk becomes a city without children as virtually every child is packed off to pioneer camp in the south. Adults have 42-day holidays—twice what they would have in the south. People come to Murmansk in their twenties, spend 30 or more years of their lives there, and then leave the city for a more comfortable existence further south.

The state encourages this. Salaries are high in Murmansk and so pensions are also generous. The retirement age is 55 for men and 50 for women compared with 60 for men and 55 for women in the rest of the USSR.

Financial Times, Tuesday, May 1, 1979

David Satter examines the latest

U.S.-Soviet prisoner exchange

Moscow Yields to ‘Interference’

The largest exchange of prisoners ever arranged between the U.S. and the Soviet Union has confirmed that despite its protest, Moscow now accepts that foreign “interference” in Soviet internal affairs is an established fact.

East-West prisoner exchanges have, of course, occurred before, beginning with that in 1962 of Gary Powers, the U-2 spy pilot, for the Soviet agent Rudolf Abel. But last week’s exchange of two Soviet spies for five Soviet dissidents represented the first time that the Soviet Union has agreed to retrieve two of its spies by granting freedom, not to foreign-agents, but to five of its own citizens.

Despite the extra difficulty of discouraging dissent when prominent dissidents are freed from prison and sent to the West, last week’s events could also lead to further exchanges resulting in freedom for Anatoly Shcharansky and Dr. Yuri Orlov, two prominent members of the group which tried to monitor Soviet observance of the Helsinki accords.

When Mr. Leonid Zamyatin, a top Kremlin spokesman, was asked on Saturday, following Soviet-French talks, about the effect of the exchange on detente, he replied angrily that detente was a question of major issues and he had nothing to say to those who saw detente in such narrow terms.

However, it was almost certainly with an eye to the SALT 2 arms treaty and the effect of Soviet treatment of dissidents on Western public opinion, that plans were made for the release of the dissidents. Although they were traded for convicted spies, there was nothing in the charges against any of them to show they had ever had any connection with a foreign power.

The best known of them is Alexander Ginzburg, a veteran Soviet dissenter who has been in and out of labour camps since the 1950s, and was sentenced to eight years imprisonment in a special-regime labour camp last July after being convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.

Mr. Ginzberg was, with Mr. Shcharansky and Dr. Orlov, a member of the now all but suppressed Helsinki monitoring group. But the principal charge against him was that he helped to distribute copies of “The Gulag Archipelago,” Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s history of the Soviet labour camp system.

The two Jewish dissidents who were freed, Mark Dymshits and Edward Kuznetsov, were also jailed on charges which had nothing to do with espionage. They were sentenced to death in 1970 for their part in an unsuccessful attempt to commandeer a light aircraft at Leningrad Airport and to fly it to Sweden from where they hoped to go to Israel.

The sentences were later reduced to 15 years’ imprisonment after widespread international protests. In 1971, Mr. Kuznetsov’s “Prison Diaries” were published in the West. Five other Jews involved directly or indirectly in what became known as the “Leningrad Affair,” were released from prison earlier this month during the visit to the Soviet Union of a delegation of U.S. Congressmen.

Another of those exchanged, Mr. Valentin Moroz, was a Ukrainian historian jailed in 1970 for anti-Soviet propaganda. After six years in prison, Mr. Moroz was moved to an institute of criminal psychiatry. When the move was announced, 20 U.S. Senators called on Mr. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet President, to allow Mr. Moroz to take up a post at Harvard University.

The last of the exchanged dissidents was Georgi Vins, leader of a faction which broke away from the officially sanctioned Baptist Church. He was jailed for inciting Soviet citizens to illegal actions. Just as he was about to be released last month, dissident sources said he had been sent back for a long prison term in Siberia after being held for seven weeks in a Moscow jail.

All five were convicted according to the normal operation of Soviet law and the exchange appears to mean that the long-standing subordination of the Soviet legal process to the political interests of the state can now be extended to include subordination to the desires and pressures of foreign states as well.

The five dissidents arrived in New York, amid intense publicity but the Soviet media carried no news of the return to Moscow of Valdik Enger and Rudolf Cheryayev, the two Soviet employees of the United Nations who were sentenced to 50 years each in New Jersey last October for receiving secret naval documents from a double agent.

It is believed that negotiations for the release of Mr. Shcharansky, and possibly Dr. Orlov, are taking place. It is speculated that a second exchange may be timed for a strategic moment to ease Senate ratification of the SALT 2 agreement.

Most observers believe that the release of other prominent dissidents will have a good effect on U.S.-Soviet relations but this remains only one of the factors that the Soviet authorities must bear in mind.

They may want good relations with the West, but releasing political prisoners to get it makes the consequences of dissent less frightening and affirms that the Soviet Union is not as resolute in rejecting attempts at outside interference in the legal process as it would like others to believe.

.

Financial Times, Monday, June 18, 1979

Tensions Between Systems Show at Summit

The first meeting between Mr. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet President, and President Carder may improve the atmosphere of Soviet-U.S. relations but, in this neutral and historic Viennese setting, there is ample evidence that interaction between the American and Soviet systems does not come without strain.

Tension derives from the fact that although the U.S. is a democracy and the Soviet Union is a dictatorship with a totalitarian structure, the Soviet leaders strive consistently to depict their country as a democracy, a feat more easily accomplished within the Soviet Union than in Vienna.

The possibility that the U.S. Senate may refuse to ratify SALT 2 has been an important concern at the summit and when Mr. Leonid Zamyatin, chief of international information for the Communist Party Central Committee, was asked at a press conference if the ratification question had been raised in the talks, he said that it had been and was agreed to be an internal matter for each country.

Mr. Zamyatin then added that Mr. Brezhnev expressed his hope and confidence that the Supreme Soviet, which he described as the Soviet legislature, would approve the treaty without amendments.

The Supreme Soviet is a purely formal, powerless body which votes unanimously to approve all policies of the Communist Party leadership and when Mr. Zamyatin’s reference to it was met with laughter in the hall, he said: “I ascribe this laughter to lack of knowledge of the Soviet structure.”

Obligations of protocol and great power equality demand that the two sides have the opportunity for an approximately equal number of press conferences, airport ceremonies and public appearances, but these activities, familiar to the Americans and to any broadly popular democratic politician, are a visible strain for the Soviet leadership.

Mr. Brezhnev has avoided making statements in public and his public appearances, either going into the talks with President Carter or coming out of them, have been as brief as possible.