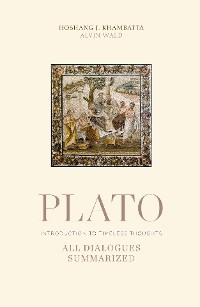

PLATO

PLATO

All Dialogues Summarized

2nd revised edition with index

Hoshang J. Khambatta

Alvin Wald

Introduction to Timeless Thoughts

Impressum

Address for correspondence: Hoshang J. Khambatta 291 Audubon Road Englewood, NJ 07631 USA e-mail: hkhambatta@nj.rr.comLibrary of Congress Control Number: 20155957300

Key Words: Plato, All Dialogues, Dialogues Summarized

CIP – Cataloguing in publication of the Deutsche Bibliothek

Plato, All Dialogues, Dialogues Summarized / ed: H. J. Khambatta / Bad Homburg:

NORMED Verlag. 2016 (1st edition)

2nd revised edition:

©2017 by Normed Verlag GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany

Normed Verlag, Englewood, NJ, USA

ISBN E-PUB 978-3-89199-013-1

ISBN MOBI 978-3-89199-017-9

ISBN 978-3-89199-018-6 (Bad Homburg)

ISBN 978-0-926592-18-6 (Englewood, NJ)

This work is subject to copyright. All rights reserved. Neither the whole nor part of this publication may be translated into other languages, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, microfilming, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission from the publisher. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is only permitted under the provisions of the German Copyright Law and a copyright fee must always be paid. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

Main Description

Plato is one of the pillars of humanity. His dialogues are an important part of our cultural heritage. Yet to read all of Plato’s Dialogues, not only requires ample time, but also a dedication that is beyond most of us. Very few will find the time and commitment to read 1500 pages of Plato’s Dialogues.

This summary of Plato’s Dialogues offers everyone access to the jewels of Western Philosophy still relevant today. Written in modern colloquial English it serves as an introduction to Plato’s work for everybody.

As of now it is the only summary of all of Plato’s Dialogues available in English in one volume. Readers seeking an accessible introduction to Plato need look no further.

Following overwhelming requests from our readers, a comprehensive index has been added to the 2nd revised edition.

The total set of Plato’s Dialogues makes it very sizeable literature. This book is an effective summary of each of the dialogues. If someone wishes to know the views of Plato without going through the vast literature of the dialogues, then this book is for that person.

K. D. Irani, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy

The City College of New York.

Reviews

These are excellent introductions to Plato’s works, and just the thing I ask my students to do when they read difficult texts. Congratulations on this good achievement. I will share this text with my colleagues here, and wish you continued success in your work.

Dr. Larry P. Arnn

President, Hillsdale College

Hillsdale, Michigan, U.S.A.

The book, which summarizes Plato’s Dialogues, is directed at a novice, a teenager who has reached a stage of understanding or an adult? This summary offers everyone an access to understanding Plato and his contribution to western philosophy. It is certainly a “must read” as it is written in modern colloquial English in one volume – an impressive feat by all accounts. Certainly it was no small accomplishment to condense the equivalent of 1500 pages of Plato’s Dialogues in some 250 summarized ones. As of now it is the only summary of all of Plato’s Dialogues available in English in one volume.

Zoroastrian Association of Greater New York

New York, U.S.A.

The total set of Plato’s Dialogues makes it very sizeable literature. This book is an effective summary of each of the dialogues. If someone wishes to know the views of Plato without going through the vast literature of the dialogues, then this book is for that person.

K. D. Irani, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy

The City College of New York.

Contents

Cover

Title

Imprint

Main Description

Reviews

Author Biographies

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface

Prologue

Dialogues

1 Euthyphro

2 Apology

3 Crito

4 Phaedo

5 Cratylus

6 Theaetetus

7 Sophist

8 Statesman

9 Parmenides

10 Philebus

11 Symposium

12 Phaedrus

13 Alcibiades**

14 Second Alcibiades*

15 Hipparchus*

16 Rival Lovers*

17 Theages*

18 Charmides

19 Laches

20 Lysis

21 Euthydemus

22 Protagoras

23 Gorgias

24 Meno

25 Greater Hippias**

26 Lesser Hippias

27 Ion

28 Menexenus

29 Clitophon*

30 Republic

31 Timaeus

32 Critias

33 Minos*

34 Laws

35 Epinomis*

36 On Justice*

37 On Virtue*

38 Demodocus*

39 Sisyphus*

40 Halcyon*

41 Eryxias*

42 Axiochus*

Index

* Plato’s authorship not authenticated

** Plato’s authorship not generally accepted

Author Biographies

Hoshang J. Khambatta was born in Bombay (Mumbai), India, and grew up in Karachi, Pakistan, where he obtained his medical degree. After post-graduate studies in Great Britain, he came to the United States of America and joined the College of Physicians and Surgeons at New York City’s Columbia University and Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. Spending the next 33 years there before retiring. Has published multiple contributions to the medical literature. During his retirement, he has participated in medical missions in Central America, India, and China. Upon totally giving up the practice of medicine, he rejoined Columbia University to read Philosophy.

Alvin Wald has been a longtime, collaborator, colleague and friend of Hoshang J. Khambatta. He is a product of New York City schools and studied in the city from grammar school through the time he received his doctorate. A long time editor of technical publications, he has recently collaborated to produce a philosophical treatise on Plato. Retired now from Columbia University, he spends many hours reading and editing scholarly works.

Dedication

I dedicate this book to my teacher, Professor Wolfgang Mann at Columbia University, for the enthusiasm for philosophy that he generated in me and to my four grandchildren, Fritz, Aliya, Emerson and Zachary.

Hoshang J. Khambatta

A teacher … can never tell where his influence stops.

Henry B. Adams, 1907

The Education of Henry Adams

To Mary Jack, my wife of untallied years. For all her never wavering love and support.

Alvin Wald

Socrates tells Ion (in the dialogue titled Ion) that his prowess in interpreting Homer’s poetry is not because of his mastery of the subject, but because of divine inspiration from Homer’s Muse. Likewise, our interpretation of Plato’s Dialogues are also not because of our mastery of the subject, but because of divine inspiration from Plato’s Muse. Lo and behold, after 2500 years, the Muse is still active.

Hoshang J. Khambatta

“I continue to learn many things as I grow old”

Solon, 630 – 560 B.C.E.

One of the seven sages of Ancient Greece

Acknowledgements

First of all, I (HJK) thank Professor Wolfgang Mann, my teacher at Columbia University in New York City. Professor Mann ignited my enthusiasm for Plato. It was after studying under Professor Mann that I thought about writing a précised edition for young and not-so-young budding philosophers. For those who are not yet familiar with ancient Greek philosophy, I hope to help them appreciate and understand the origins and principles of philosophical thinking.

Next, I (HJK) asked my eldest grandson, 17-years old, Cyrus Fritz Pachmann who is a student at the International School in Frankfurt, Germany (Class of 2016), whether he would read the manuscript, as he is part of the target audience. He agreed and found the book thought provoking and easy to follow. He also made many helpful suggestions for which I am very thankful.

Next, I (HJK) would like to thank my wife Renate, son Gustav and his wife Jennifer, daughter Sonja Khambatta and her husband Thomas Pachmann for their steadfast support during the period it took to write the manuscript.

Next, I (HJK) would like to thank my Editor/Publisher, Franz Reuter, at Normed Verlag for guiding me through the process and humoring me along the way.

We would like to thank Emeritus Professor K. D. Irani of The City College of New York for reviewing the manuscript and for his considered comments and criticisms of our work.

We wish to thank Adjunct Professor of Philosophy Christine Pries, Barnard

College, Columbia University, New York for reviewing parts of the manuscript and for her useful comments.

HJK is fully responsible for interpreting Plato. If there are any errors they are his. AW is responsible for editing.

We perused several English translations of Plato’s Dialogues but finally placed a bigger emphasis on the book used by (HJK) for the course work at Columbia University. John M. Cooper, Editor and D. S. Hutchison, Assistant Editor. Plato Complete Works (Indiana/Cambridge, Hatchett Publishing CO 1997).

We have referred to open source material available on the internet.

Copyright permission courtesy of Branislav L. Slantchev for use of the image of Plato’s Academy Mosaic, from National Archeological Museum, Naples, Italy.

Preface

Plato is considered to be one of the greatest philosophers of all times, and many consider him to be the father of philosophy. He was born in Athens in 427 B.C.E. into a rich, aristocratic family and he died in 347 B.C.E. at the age of 81. In his late teens or early twenties he began to frequent a circle of Athenian thinkers led by Socrates. If Plato is the father of philosophy, then Socrates, who died in 399 B.C.E. when Plato was 28 years old, would be the grandfather. Socrates’ death had a tremendous influence on Plato who then traveled the known world and engaged with other philosophers. No original works of Socrates have survived, and what we know of him today is found in Plato’s writings. In 380 B.C.E. Plato opened a school of higher education in the sacred groves of Academus in the Attic country-side near Athens. He offered lessons in mathematics, politics and philosophy. Under his leadership this academy became a major institution, attracting leading scholars from all over Greece. Aristotle attended as a student in 367 B.C.E. and remained as a teacher up to the time of Plato’s death.

Plato began to write after Socrates’ death and continued for the next 50 years until his own death. These writings are in the form of dialogues. Plato and Socrates are not handing down truth. They are encouraging you to think for yourself by considering the available alternatives. Socrates and Plato did not believe that they had new knowledge to hand down, they wanted readers to reason and think and reflect on how to improve themselves. Truth is attained if one takes time to think; it is not a personal revelation for which a person can claim credit. Plato never appears in the first person in his dialogues. What he writes he credits to others, and he makes no claims to absolute wisdom. Truth must be arrived at by each of us on our own; we must gain the capacity to interpret and reinterpret. This is where Socrates and Plato differ from earlier philosophers, known as Sophists, who made claims to possess wisdom and truth that they would impart to their followers.

We do not have Plato’s work in the original. It is available as dialogues from transcriptions made and compiled by Thrasyllus, who came from the Greek city of Alexandria in Egypt. He was an astrologer and Platonist philosopher in the first century C.E., nearly 400 years after Plato’s death. In essence, Thrasyllus was responsible for the first edition of Plato’s complete work gathered together in one place. For some of the dialogues, the authenticity of Plato’s authorship has been challenged. Thrasyllus included these, even though he called them spurious. We, too, have included them in this volume. In the recent past the authenticity of a few more dialogues has been challenged by scholars, and we have made a note of that in this publication. While we have no knowledge of the order in which the original dialogues were written, Thrasyllus arranged them in a thematic fashion, and we will follow that order. Though we have numbered the dialogues in this volume, there is no chronological significance to the order in which they are numbered and presented. Regards the order we have followed the lead of classical scholars. The numbering has been done for easier access. The first four dialogues are known as the Socratic dialogues and have a theme of justice and legislation. There is then another group in which Plato introduces his theory of Forms. This is the concept of eternal non-physical knowledge that is obtained by abstract thought.

The lessons of Plato and Socrates are just as valid today as they were two-and-a-half thousand years ago. This book is directed at the novice, a teenager who has reached an age of understanding or an adult who has not been exposed to ancient Greek philosophy, but has a desire to learn. We hope that readers of this book will have the curiosity to consult the original texts, albeit in translation. If this hope becomes a reality, then our mission will have been fulfilled. However even if our efforts here only produces an interest in or appreciation of philosophy, we will be satisfied. All of the dialogues in our volume are preceded by a short “overview” to facilitate reading. The overview is then followed by a shortened version of the original dialogue, which is our interpretation, in which we have tried to maintain the feel, and semblance of the original dialogue format.

Hoshang J. Khambatta

December 2015

Prologue

Plato’s academy, a beautiful place in the Mediterranean. Students learning under the olive trees in the warm breeze. What better way than in a beautiful garden is there to question and discuss the nature of friendship, justice, society and science. It is why I chose this image showing Plato with six of his students from the Villa of T. Siminus Stephan in Pompeii, Italy. It shows that though we cannot always choose the gardens where we think, we can nurture our need for answers through questions. Dialogue has not lost its relevance, in fact it has become more vital than ever as our civilization continues to struggle in how we see the world, our society and ultimately ourselves. That is what makes Plato’s Dialogues classics.

Plato’s Academy, Mosaic from Villa of T. Siminius Stephanus, Pompeii

(Photo Courtesy of Branislav Slantchev)

1 Euthyphro

Overview: Euthyphro claims to know all about piety and impiety and also the meaning of pious and impious. So sure of himself is he, that he is prosecuting his own father for the murder of a murderer. When challenged by Socrates he is unable to explain his beliefs. Instead, he talks about prayer and sacrifice to The Gods and about whom and what The Gods love. All his boasting of knowledge comes to naught. It appears that he fears some imagined displeasure of The Gods that he would not have to endure if he prosecutes his father.

We notice that throughout the dialogue, the main line of any inquiry by Socrates is “what is.” He wants a defining answer to his questions. Euthyphro was unable to answer Socrates’s question. Maybe Plato is trying to tell the reader that piety is a person’s ability to become morally as good as possible and not any ability to please The Gods.

Socrates and Euthyphro run into each other near the Athens magistrate’s office. Euthyphro appears to be confused and surprised, asking Socrates if some one is indicting him or the other way round. Socrates says that, indeed, a young Athenian by the name of Meletus is indicting him for corrupting the young and for creating new Gods while not believing in the existing Gods, and therefore of impiety towards The Gods, whose displeasure will then fall upon the city. Socrates asks Euthyphro what brings him to the magistrate’s office? Euthyphro replies that he is prosecuting his own father for murder, which is a pollution and therefore displeasing to The Gods. Socrates inquires whether the victim of this crime was a friend, a relative or a stranger. Euthyphro answers that the relationship was not important; it only matters if the killer acted justly or not. Euthyphro explains that the victim had killed one of his father’s slaves while working on the family farm. Euthyphro’s father had gotten very angry and had the victim bound and thrown into a ditch. The father then sent a messenger to Delphi to ask what should be done next. However, before the messenger returned, the victim died. Now, all of Euthyphro’s relatives are angry with him because he is suing his father even though the victim was a murderer and his father had not deliberately killed him. Furthermore, they point out, it is impious to prosecute one’s father. Euthyphro feels that his relatives’ ideas of piety are wrong. His father is responsible for the victim’s death, and this should be avenged to please The Gods.

Socrates and Euthyphro then discuss how The Gods constantly fought amongst themselves as portrayed in the epic Greek sagas and poems of old. They talk about Zeus, the most just amongst The Gods. Euthyphro reminds Socrates that Zeus pursued his father and castrated him because he unjustly swallowed his sons, but now some people are upset that he, Euthyphro, is prosecuting his own father.

Socrates then asks that, as Euthyphro knows so much about the pious and the impious, whether he can explain what a person should do in such a situation. Euthyphro says that his action in suing his father is the pious thing to do, and that it does not matter that he is his father’s son. Socrates says that he, too, finds some of the conflicting things said about The Gods to be confusing. He says that such confusion may be the reason why Euthyphro is prosecuting his father. Socrates then inquires about what makes an action pious or impious. Euthyphro answers that what is dear to The Gods is pious and what is not dear is impious. Socrates rephrases the statement, saying that actions or persons dear to The Gods are pious and the opposite are impious and Euthyphro agrees to this interpretation. Socrates then reminds Euthyphro that they had agreed earlier that The Gods often disagreed with each other. Therefore, the two of them should try to figure out what causes those disagreements. Here Socrates concludes that what some Gods consider beautiful others find ugly and that different Gods find different things good or bad. Similarly, The Gods are discordant about justice and injustice, furthermore, some Gods hate or love other Gods. By this thinking, Euthyphro’s punishing his father may be pleasing to Zeus but displeasing to Cronus. Other Gods may have differing views on this matter.

Euthyphro then adds that no person or God says that someone who has done wrong should not be punished. Rather, both man and The Gods agree that the first thing to be determined is who has done wrong. The matter centers on whether the deed in question was just or unjust. Socrates asks Euthyphro to show him if any of The Gods would call his father’s action unjust, Euthyphro agrees that this is a difficult question but then asserts that piety is what all The Gods love and the converse, namely impiety, is what all The Gods hate. Socrates turns this definition around and asks whether that which is pious is loved by the Gods because it is pious or it is pious because it is loved by The Gods. Euthyphro is unable to answer this question and Socrates gives more examples of this paradox. There is a difference between something carried and something carrying, something led and something leading, something seeing and something seen. Socrates adds that something loved is different from something loving. Hence, we would say that an action is loved because it is pious but not pious because it is loved. Socrates argues that what The Gods love does not make action pious, nor does being pious imply being loved by The Gods. After this round of circular reasoning, Socrates again asks what piety is. He asks whether all or some of that which is just is pious, or whether all or some of that which is pious is just?

Here Socrates digresses a little and quotes an ancient poet who said that “where there is fear there is shame.” Socrates notes that he disagrees with the poet, explaining that men fear illness or poverty but that there is no shame in this fear. Someone who feels shame or embarrassment fears a ruined reputation. So shame is the more encompassing. Where there is shame there is fear, but the reverse is not true. Socrates is trying to show that where there is piety there is also justice, but that where there is justice there is not always piety. Euthyphro adds that the godly and the pious are part of the just who are concerned with the care of The Gods, while the care of man is the human part of justice. Socrates asks Euthyphro to explain what he means by the concern of The Gods and adds that so far Euthyphro has failed to explain what piety is. Euthyphro replies that man knows how to say what is pleasing to The Gods by prayer and sacrifice. These are pious actions, pleasing both to The Gods and to the state. Socrates replies that prayer is begging from The Gods and sacrifice is giving gifts to The Gods. Hence, piety would mean, having the knowledge of how to give to The Gods and how to beg from them. Socrates calls this piety a kind of give and take trade with The Gods. In such trade, men receive blessings from The Gods in return for piety. This definition means that piety is what is pleasing to The Gods, not necessarily what is beneficial to them. Socrates bemoans the fact that he has not yet learned what piety is. He adds that Euthyphro has no clear knowledge of what is piety and impiety but that, if he had such knowledge, he would not have tried to prosecute his own father. It is on his fear of The Gods and the risk of offending them and not piety, that he has based his decision to prosecute his father. Euthyphro should have a clear knowledge of what piety is if he intends to prosecute his own father. At this point, to escape further questioning, Euthyphro claims a prior engagement and departs.