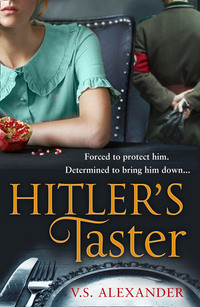

Hitler’s Taster

Karl and I sat near the rear in plush high-back chairs. They were somewhat stiff, and I wondered if they’d be uncomfortable to sit in through an entire movie. When the alley went dark, Karl reached across and touched my hand. Warmth spread through my fingers and up into my arm. The shock touched my heart and I struggled to catch a breath.

‘Is something wrong?’ Karl asked.

‘No,’ I whispered. ‘I tasted tonight for the first time. Perhaps it’s a reaction to the food.’

Karl twisted in his seat and took my hands. ‘If you’re sick, I will get the Führer’s personal physician.’

I leaned back. ‘Please, Karl, I’m fine. Let’s enjoy the movie.’

He nodded and relaxed somewhat. The lights flickered, the music swelled from the speakers and we turned our attention to the film. I made sure to keep his hand in mine. He squeezed my fingers as Scarlett teased the Tarleton twins. I had the same reaction when, later in the film, Scarlett kissed Rhett Butler.

About one in the morning, a telephone call interrupted the film. We were only about two-thirds of the way through, but the picture was finished for the evening. Those who wanted to see the ending would have to wait for another time. Karl escorted me back to my room, kissed my hand and disappeared down the hall. I got into bed and dreamed that night of making love to him.

Over the days, my fear of tasting lessened. One afternoon, I called my parents for the first time since arriving at the Berghof and told them I was working with Hitler. The Reich had informed them previously of my service. However, I did not tell them what I was doing. I could tell my father was not pleased with my new position because his silence gave away his thoughts. I also knew someone, probably an SS man, was listening to our conversation. I suspected my father did as well.

My mother was more effusive and pressed me about my job. I told her I was in service to the Führer and left it at that. It was best not to give either of them any more information. When I hung up, it struck me how much I lived in a world of distrust and fear. Perhaps my father’s cold replies amplified what I was feeling. At the Berghof, we lived in a monastic world: secluded, insular, broken off from the realities of the war. Hitler and his generals bore the psychological brunt of the fighting. We never saw or heard the reported rages, or experienced the tensions that apparently permeated this mountain retreat. We only heard rumors. We could either choose to believe or not. I didn’t like feeling this way because I wanted the world to be ‘normal.’ After the conversation with my parents, I realized how far and how fast I’d slipped away from the everyday. I wondered whether everyone in Hitler’s service felt the same. I was being seduced by the singular drama in which we played. We were all Marie Antoinette asking the world to eat cake while the earth burned to ashes around us.

After about two weeks, I finally tasted a meal without some degree of shaking. Ursula and the cooks had teased me, so unmercifully, in fact, that eventually I forced myself to relax. They assured me that no poisons would get by them. The ‘last meal’ became a joke around the kitchen. Despite their assurances, I still suffered from a nervous stomach now and then.

Captain Weber and I spoke often when we passed each other in the halls and sometimes we enjoyed leisurely conversations in the kitchen. Cook raised as much of a fuss as she could, but it was Karl’s right to oversee as he saw fit. One night he suggested we go to the Theater Hall for an impromptu dance. I, of course, accepted with Ursula’s urging.

Karl called for me at my room and accompanied me up the slope to the Hall. The air was fresh, the night chilly, as we walked. A small dance floor had been formed by pushing chairs aside to the walls. The lamps were dimmed, barely enough to light the room. Records, mostly waltzes, crackled out of an old table phonograph. The music flowed into the room from a gold-colored, blossom-shaped speaker. Two other couples were dancing. A few of the men, lacking women, danced together, not touching each other except for their hands. They shot looks of envy our way when Karl pulled me close and swung me into a waltz. We flowed naturally into each other.

The night melted into stars and warmth. I loved being next to Karl and, judging by the content smile on his face, he loved me as well. We danced for several hours, hardly saying a word. If love was an energy, a force, it passed between us that night. When I finally left his arms, my body tingled.

As we were leaving the Hall, we heard a cough. Karl grabbed my hand tightly and guided me out of the building. I looked back. The Colonel walked out of the shadows, cigarette in hand, the smoke drifting through the dim light. His gaze followed us as we left.

‘How long has he been watching us?’ I asked Karl.

He did not look back. ‘All evening,’ he said.

One afternoon in late May, I accompanied Karl and Ursula on a trip to the Teahouse. It was my first visit. I had seen it once from the terrace that ran along the north and west sides of the Berghof. I sneaked a peek at its round turret rising through the trees below when no one was about but an SS guard enjoying the air. He recognized me and didn’t mind that I shared the view.

The mountains to the north were often misty and veiled in clouds, but the first day I saw the Teahouse the sky was crisp and blue. Looking out upon the scenery, I realized why Hitler had chosen this particular spot as his own. He’d purchased the property – claimed it, some had said – and begun renovations a short time later. The view gave its owner the psychological superiority of one who might believe he was a god. To look upon the magnificent rocky peaks was to feel on top of the world while those below were mere specks, dirt beneath his feet. Hitler was indeed master of all he surveyed.

Karl, Ursula and I set off to the Teahouse shortly after one o’clock. The blue sky above the Berghof held today as well, but a band of high clouds was approaching from the northeast. We walked down the driveway and then cut off on a trail that descended through the forest by way of a wooded path. At one magnificent bend, rails of hewn logs kept the walker from tumbling over the precipice of the Berchtesgaden valley. A long bench had been constructed there so Hitler could ponder the magnificent view to the north. Karl told us that Eva and her friends liked to use the rails as a kind of gymnastic bar, balancing upon them and pointing their legs over the cliff, at least for the sake of photographs. She was always posing and using her new film camera, he said. Hitler was often uncomfortable with her filming, but grudgingly obliged her hobby.

The Teahouse, less than a kilometer from the Berghof, soon came into view. It was like a miniature castle planted on a rocky hillside. The path ended at stone steps to its door. Karl had a key because the kitchen staff was so often called to serve there.

‘I really shouldn’t be doing this, but I want you to see it,’ he said. ‘It’s quite charming. Hitler relaxes here and invites others to join him. He’ll be down later.’

Karl opened the door and Ursula and I peered inside. A round table decorated with flowers and set with silk tablecloths, sparkling china and polished silver sat near the middle of the room. Plush armchairs decorated in an abstract floral pattern of swirling bellflowers added to the medieval atmosphere of the turret. A kitchen and offices lay behind this large circular room. We stepped inside and Karl urged me to sit in one of the chairs. I did and luxuriated in its soft cushions.

‘That’s where he sits,’ Karl said.

I jumped out of the chair.

Ursula laughed. ‘Scaredy-cat,’ she said. ‘He’s not here.’

‘Why did you tell me to sit there?’ I asked Karl, irritated by his prank. ‘I don’t want to get into trouble.’ I felt foolish.

‘You won’t. Sit and enjoy the view.’ I returned to the seat and looked out the windows that encircled the front half of the tower while he and Ursula whispered in the doorway.

‘What are you two plotting?’ I asked.

Karl turned to me, his face sullen. ‘Nothing. I’m talking with Ursula about her mother – she’s been ill, you know.’ The night Karl and I had gone to see Gone with the Wind, Ursula had been called to Munich.

I sat for several more minutes as they continued their secretive discussion. Finally, I got up, explored the other tables and chairs and then stood behind them. They abruptly stopped their conversation when I got too close.

‘We should be getting back,’ Karl said. ‘We can’t hang about here too long.’

As we walked, I wondered why we had come in the first place. I didn’t have a good feeling about our visit to the Teahouse. Something gnawed at my stomach and I knew my discomfort centered on Karl and Ursula. They were up to something.

CHAPTER 5

Karl informed us that Hitler often stayed at the Berghof for only a short time before leaving for another headquarters or hiding place. When Hitler was in residence, a giant Nazi flag flew over the grounds. As it turned out, he wasn’t even at the Berghof for about two weeks in May. I wasn’t sure where he went, but Karl, on the sly, told me it was to the ‘Wolf’s Lair.’ To foil assassination attempts, the Führer kept his travel schedule secret and often switched trains or flights at the last moment or showed up early or late for appointments. He’d used this tactic for years, and it had served him well, particularly since the war broke out.

A rumor circulated that Hitler was holding a reception at the Teahouse for kitchen staff before he left on his next trip. It would be the first time I had a chance to meet the leader of the Reich. I asked Karl about this and he confirmed it was true.

After breakfast the next morning, everyone was in high spirits and anticipation about ‘tea’ with the Führer. A light rain fell, but it did not dampen our gay mood. Cook wanted me to take inventory from the greenhouses and record food items, in addition to my tasting duties, so I was late getting back to my room.

‘Eva has instructed everyone to wear traditional Bavarian garments,’ Cook told me. ‘There will be a costume on your bed.’

‘Why is dressing up so important?’ I asked her.

‘Because Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s personal photographer, is here. He and Eva thought it would be a good opportunity to capture the benevolent spirit of the Führer as he entertains and thanks his staff.’ She chuckled. ‘Eva loves to dress up. That’s really why we’re doing it.’

When I went back to my room, I interrupted Ursula. She was already dressed in her Bavarian costume. I really had no fondness for the hose, petticoats, the flouncy dress and puffy sleeves of the garment. Ursula sat on her bed, sewing her apron. She turned quickly away from me when I entered.

‘You’d better get ready,’ Ursula said, looking back over her shoulder. Her fingers trembled and the needle slipped from her hand.

‘Are you all right?’ I asked. ‘Is there a problem with your apron?’

She shook her head. ‘I’m shaky because I haven’t eaten. I need to get to the kitchen for some food.’ She began sewing again and stitched across the apron’s left pocket.

‘There’s not much to eat now. The staff is preparing lunch, but I wouldn’t be concerned about me getting ready. I’m sure it’ll be after four before we’re called to the Teahouse. We’ve got plenty of time.’

Ursula sighed. ‘Yes, plenty of time.’

She went back to her work as I inspected my dress and its trimmings. ‘I don’t have an apron. Do I need one?’

Her eyes dimmed. ‘I don’t know. You might ask Cook. This one was given specifically to me.’

I stretched out on my bed with a book. ‘The weather is so nasty it’s a good day for reading.’

Ursula threw the apron and needle on her bed. ‘Can’t you take a walk or find something to do?’

I sat up, shocked at her harsh tone. ‘What’s wrong? I’ve never seen you so upset. Is it your mother?’

She buried her face in her hands and cried. I crept over to her, sat behind her and cradled her shoulders. This made her sobbing even worse.

‘Yes,’ she said between gasps. ‘I have no family now. Both of my brothers are dead because of the war. My father is already dead and my mother is dying. I don’t care if we lose this war – I’ve already lost everything. My brothers were all I had.’

I turned her so she faced me, and wiped her tears with a handkerchief. ‘You must be strong and not let your troubles overcome you.’

Ursula pushed me away. ‘You say that so easily because you still have your family. Wait until they are gone. Then you’ll see how hard it is.’ She collapsed on the bed.

Saddened by her mood, I got up and stared out the window. The mountains were lost in the silver mist and fog. On days like this, the Berghof’s air of invincibility vanished. ‘I’ll leave you alone, but you only have to ask if you need my help.’ I found my poetry book on the shelf. I knew Hitler was still eating breakfast and after that he would meet with his military staff for a few hours in the Great Hall. I had no idea where to go. ‘I’ll be back later to get ready.’

Ursula continued working on her checked apron. A few flecks of white powder shone on the red fabric. I closed the door, not thinking much about what I’d seen.

I sat at a table on the corner of the terrace. No one else was around because of the cold rain. The wind blew mist under the sun umbrella, making reading uncomfortable. After a few minutes, I gave up and found a vacant chair in a hallway. Eva happened to walk by with her two Scotties. The dogs were used to guests at the Berghof but still insisted on sniffing me. Eva stood before me, looking bored and out of sorts; she wore a dark blue bellflower skirt with a matching bolero jacket. I admired the diamond-encrusted bracelet on her left wrist.

‘The Führer gave me this.’ Eva jangled the bracelet and laughed casually; however, there was no humor in her voice. She leaned down as if to whisper in my ear. ‘If you promise not to tell anyone, I’ll let you in on a secret.’

I was astounded at her intimacy with me – someone she barely knew. I didn’t know what to make of it. She must have been lonely and in need of a friend. Cook and others in the kitchen had hinted at Eva’s personality. Somewhat flighty, haughty when she needed to be, entitled, but also flirty and fun with her friends. Because I’d had so little contact with her, I wanted to make up my own mind.

‘What’s your name?’ she asked.

‘Magda Ritter.’

She continued her conversation, asking me where I was born, questioning me about my parents, my schooling and how I came to work at the Berghof.

I answered everything truthfully. She shook my hand, but didn’t give her name. Obviously, I was expected to know who she was.

She studied me with her blue eyes. ‘I’ve seen you in the kitchen. What do you do?’

‘I’m a taster for the Führer.’

She beamed like a benevolent member of the clergy. ‘Ah, a wonderful position. You are protecting the life of the most important man in the world. You don’t know how he depends on his staff to guide him through these terrible times.’

I smiled because she knew so little of me and tasting. No matter how magnificent the meal, you wondered if it was your last. ‘I would never expect the Führer to know who we are.’

‘Of course he does. People like you lift him above the fray. If there was any threat to the Berghof, he would be the first to throw himself at the enemy. He would protect his staff until all danger had vanished.’

I nodded, uncertain of what she was getting at, but clearly Eva wanted to paint him as a kind and congenial man. Cook had told me stories about his loving interactions with Blondi, his dog, his fond dealings with Speer’s children and Eva’s guests. His closest associates believed the Führer could do no wrong.

Eva knelt in front of me and patted the Scotties. They sat patiently at her feet during our conversation. ‘Why are you reading here?’

‘Because my roommate is in no mood for company.’

She turned her attention from the dogs and put her hand upon mine. ‘I know how you feel. The Führer often ignores me, sometimes for days at a time, because he is so busy. When he leaves for other parts of the Reich, I go to my little house in Munich. Life can be lonely and boring there, too.’

It was hard for me to feel sorry for her with the world at her feet while others suffered, but I sensed that even as wealth and power lay within her reach she wasn’t happy. Her dejected expression added to her sudden melancholy mood.

‘Well, I’ve said too much and I need to get ready for the reception this afternoon,’ she said. ‘You will be going? If so, I hope you enjoy the dress I provided.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘it was nice of you to do so.’ I studied her clothes. ‘You look beautiful now. Why would you change?’

She rose to her feet and the dogs jumped up as well. ‘It’s one of the few pleasures I have. Dresses, makeup and jewelry. When I look beautiful, he is happy.’

She walked away and I called out, ‘What about the secret you were going to tell me?’ I regretted my silly words as soon as they left my lips.

Eva turned, her skirt swirling around her. ‘But I’ve already told you. I’ll see you later.’ She took a few steps and faced me again. ‘Why don’t you read in the sunroom? No one’s there and you shouldn’t be disturbed. If anyone asks, tell them I gave you permission.’

I thanked her and watched as she disappeared down the hall with the dogs at her feet. The companion of the most powerful man in Europe was lonely – that was her ‘secret.’

I walked to the sunroom, which was pleasant for reading even though its namesake was hidden by the clouds. It was in the original part of the old house and was furnished with lounge armchairs, a table and four rather uncomfortable slat-back chairs. I sat in one of the plush armchairs and spent most of my time looking out the wide picture window rather than concentrating on my poetry. Even though Eva said I could be there, I felt out of place on this side of the Berghof, away from my quarters.

In mid-afternoon, I returned to my room. Ursula was gone. I put on my costume and looked in the small mirror attached to the wall. There was nothing glamorous about me; in fact, I felt like a clown in an outfit that would be ridiculed outside of a beer hall. But Eva had ordered it and I felt compelled to comply. My costume didn’t include an apron. Karl rang my room about three and said he was on his way to the Teahouse and would see me there about four. Hitler was notorious for missing appointments. We expected it might be five before he even showed up.

Several members of the kitchen staff joined me when it came time to leave. Our mood was light and jovial. We even stopped at the overlook, but the valley was obscured by clouds, so there was little to see.

Gradually, the Teahouse came into view out of the mist like something from a fairy tale. Nazi flags and bunting festooned its turret, and a banner above the door proclaimed: Thank You for Your Service.

Inside, candles lit the room and a cheery fire in the hearth chased the damp away. Most of the kitchen staff were gathered inside and sat around a few small tables. The massive one with the view of the mountains was reserved for Hitler and his guests. Bavarian crèmes, cookies and apple cake, the Führer’s favorite, were displayed on fine china. Orderlies stood ready to serve the treats to the crowd. Fine champagne sat in ice buckets at each table within easy reach of the guests.

Karl observed the crowd from the kitchen entrance. Ursula was nowhere to be seen. I wondered how we could all cram inside the Teahouse. If it became too crowded, I decided, I would join Karl in the kitchen.

Franz Faber, the young officer Ursula disappeared with the night we went for a walk to the SS barracks, joined Karl. They talked for a time until Karl saw me. He left Franz and, sporting a broad grin, whispered in my ear, ‘You look rather silly.’

I scowled and then laughed. ‘I agree. I’ll be upset if Eva and Hoffmann are not here with their cameras.’ I looked around the room. ‘Have you seen Ursula?’

‘She’s making tea.’

I glanced through the turret windows. There was no sign of Hitler, Eva or their guests. The rain had let up, so Karl and I walked outside and stood near the steps leading to the entrance, stealing a few moments together. Our quiet was interrupted by the sudden, frenzied barking of a dog. That was followed by shouts and a general commotion.

Karl sprinted up the steps.

I followed and peered inside the door, careful to stay out of the way. Karl, Franz and the Colonel stood near the kitchen entrance. Behind them, I saw the pale, stricken face of Ursula. She wore her costume and the apron she’d been working on. The Colonel clutched a furiously barking black shepherd. The crazed animal snapped and growled at Ursula.

Over the uproar, Franz shouted, ‘It isn’t possible.’

The Colonel brushed him aside, gave control of the dog to Karl and then pulled Ursula from the kitchen into the circular room. She held a silver teapot in her right hand.

The Colonel took the teapot from Ursula and ordered her to take a cup from one of the small tables. Her hands shook as she obeyed his order.

Franz rushed to her and said to the Colonel, ‘I’m sure this is a mistake. Fräulein Thalberg would never poison the Führer.’

‘Shut up,’ the Colonel commanded. ‘Get away from her.’

Karl stared at me. Horror spread across his face. My heart pounded as I leaned against the door frame. The Colonel, still carrying the tea, grabbed Ursula roughly by the arm and pulled her down the steps of the Teahouse. He ordered her to hold out the cup; then he poured the hot liquid into it. He sniffed the steam as it rose in milky wisps in the air.

‘Drink it,’ he said. His lips formed a vicious smile.

Franz stood frozen in the doorway. Karl, still restraining the barking dog, stared in disbelief.

Ursula looked blankly at the Colonel. She lifted the cup to her lips and drank it in one draught.

The Colonel took back the cup and waited.

Nothing happened for a few long minutes as Ursula focused her gaze upon the ground. Then, slowly, her body convulsed. Her eyes rolled back in her head and she collapsed on the path. Franz started to run to her, but Karl and a member of the kitchen staff held him back.

Down the path, conversation and laughter filled the air. Hitler, with a walking stick in hand, strolled ahead of his entourage. He was accompanied by Eva and the guests, no more than fifty meters from the Teahouse. She carried her camera in her quest to get photographs of the Führer. She darted ahead of him at one point to snap pictures.

I watched in disbelief as Ursula, her skin and lips turning blue, lay unconscious on the ground. The Colonel did nothing. Cook had told me about the body coloration as one of the symptoms of cyanide poisoning. It led to an unconscious state and respiratory failure – a lack of oxygen. The convulsions, her gasps, continued until her mouth gaped open. With one final breath, her body shook and then her arms fell lifeless by her sides.

Karl ordered the staff to stay inside, although the whole event could be seen through the Teahouse windows.

Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s gray-haired photographer, rushed up and snapped a few pictures of the body. Hitler stopped the procession and motioned for the Colonel to come to him. With the teapot and cup in hand, he approached the Führer. I couldn’t hear their conversation, but after a short time Hitler turned and said something to the group. Amid looks of astonishment, they retreated and disappeared into the mist.

The Colonel poured out the contents of the pot on the trail and addressed Karl. ‘You should have better command over your staff, Captain. Get a couple of men to take the body to the doctor’s office for an autopsy.’ He grabbed his dog’s leash. The animal wanted to sniff Ursula’s body. ‘You and Faber – in my quarters in an hour. In the meantime, make sure the Teahouse is cleaned up. No one should eat or drink anything. Keep only the items that are sealed.’ He handed Karl the teapot and the cup.