The Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

The towns of the Basque provinces appear not to have been much maltreated during the Carlist war; not so the villages, most of which present a melancholy aspect of ruin and desolation. The churches, built so as to appear more like keeps of castles, have mostly withstood the shock. The destruction was oftener the result of burning than of artillery. The lover of the picturesque offers his silent gratitude to the combatants on both sides, for sparing, although unintentionally, some of the most charming objects of all Spain.

Among the most striking of these is Hernani. It is composed of one street, of the exact required width for the passage of an ordinary vehicle. This street is a perfect specimen of picturesque originality. The old façades are mostly emblazoned with the bearings of their ancient proprietors, sculptured in high relief. On entering the place, the effect is that of a deep twilight after the broad blaze of the sunny mountains. This is caused by the almost flat roofs, which advance considerably beyond the fronts of the houses, and nearly meet in the centre of the street: the roof of each house is either higher or lower, or more or less projecting, than its neighbour; and all are supported by carved woodwork, black from age. The street terminates on the brow of a hill, and widens at the end, so as to form a small square, one retreating side of which is occupied by the front of a church covered with old sculpture; and the diligence, preceded by its long team of tinkling mules, disappears through the arched gateway of a Gothic castle.

In this part of Spain one does not hear the sounds of the guitar; these commence further on. On Sundays and holydays, the fair of Tolosa, and of the other Basque towns, flourish their castagnettes to the less romantic whinings of the violin; but, in traversing the country, the ear is continually met by a sound less musical, although no less national, than that of the guitar—a sort of piercing and loud complaint, comparable to nothing but the screams of those who have "relinquished hope" at Dante's grim gateway.

These unearthly accents assail the ear of the traveller long before he can perceive the object whence they proceed; but, becoming louder and louder, there will issue from a narrow road, or rather ravine, a diminutive cart, shut in between two small round tables for wheels. Their voice proceeds from their junction with the axle, by a contrivance, the nature of which I did not examine closely enough to describe. A French tourist expresses much disgust at this custom, which he attributes to the barbarous state of his neighbours, and their ignorance of mechanical art; it is, however, much more probable that the explanation given by the native population is the correct one. According to this, the wheels are so constructed for the useful purpose of forewarning all other drivers of the approach of a cart. The utility of some such invention is evident. The mountain roads are cut to a depth often of several yards, sometimes scores of yards, (being probably dried-up beds of streams,) and frequently for a distance of some furlongs admit of the passage of no more than one of these carts at a time, notwithstanding their being extremely narrow. The driver, forewarned at a considerable distance by a sound he cannot mistake, seeks a wide spot, and there awaits the meeting.

You need not be told that human experience analysed resolves itself into a series of disappointments. I beg you to ask yourself, or any of your acquaintances, whether any person, thing, or event ever turned out to be exactly, or nearly, such as was expected he, she, or it would be. According to the disposition of each individual, these component parts of experience become the bane or the charm of his life.

This truth may be made, by powerful resolve, the permanent companion of your reflections, so as to render the expectation of disappointment stronger than any other expectation. What then? If you know the expected result will undergo a metamorphosis before it becomes experience, you will not be disappointed. Only try. For instance,—every one knows the Spanish character by heart; it is the burden of all literary productions, which, from the commencement of time, have treated of that country. A Carlist officer, therefore,—the hopeless martyr in the Apostolic, aristocratic cause of divine right; the high-souled being, rushing into the daily, deadly struggle, supported, instead of pay and solid rations, by his fidelity to his persecuted king;—such a character is easily figured. The theory of disappointments must here be at fault. He is a true Spaniard; grave, reserved, dignified. His lofty presence must impress every assembly with a certain degree of respectful awe.—I mounted the coupé, or berlina, of the Diligence, to leave Tolosa, with a good-looking, fair, well-fed native, with a long falling auburn moustache. We commenced by bandying civilities as to which should hold the door while the other ascended. No sooner were we seated than my companion inquired whether I was military; adding, that he was a Carlist captain of cavalry returning from a six months' emigration.

Notwithstanding the complete polish of his manners in addressing me, it was evident he enjoyed an uncommon exuberance of spirits, even more than the occasion could call for from the most ardent lover of his country; and I at first concluded he must have taken the earliest opportunity (it being four o'clock in the morning) of renewing his long-interrupted acquaintance with the flask of aguardiente: but that this was not the case was evident afterwards, from the duration of his tremendous happiness. During the first three or four hours, his tongue gave itself not an instant's repose. Every incident was a subject of merriment, and, when tired of talking to me, he would open the front-window and address the mayoral; then roar to the postilion, ten mules ahead; then swear at the zagal running along the road, or toss his cigar-stump at the head of some wayfaring peasant-girl.

Sometimes, all his vocabulary being exhausted, he contented himself with a loud laugh, long continued; then he would suddenly fall asleep, and, after bobbing his head for five or six minutes, awake in a convulsion of laughter, as though his dream was too merry for sleep. Whatever he said was invariably preceded by two or three oaths, and terminated in the same manner. The Spanish (perhaps, in this respect, the richest European language) hardly sufficed for his supply. He therefore selected some of the more picturesque specimens for more frequent repetition. These, in default of topics of conversation, sometimes served instead of a fit of laughter or a nap: and once or twice he hastily lowered the window, and gave vent to a string of about twenty oaths at the highest pitch of his lungs; then shut it deliberately, and remained silent for a minute. During dinner he cut a whole cheese into lumps, with which he stuffed an unlucky lap-dog, heedless of the entreaties of two fair fellow-travellers, proprietors of the condemned quadruped. This was a Carlist warrior!

The inhabitants of the Basque provinces are a fine race, and taller than the rest of the Spaniards. The men possess the hardy and robust appearance common to mountaineers, and the symmetry of form which is almost universal in Spain, although the difference of race is easily perceptible. The women are decidedly handsome, although they also are anything but Spanish-looking; and their beauty is often enhanced by an erect and dignified air, not usually belonging to peasants, (for I am only speaking of the lower orders,) and attributable principally to a very unpeasant-like planting of the head on the neck and shoulders. I saw several village girls whom nothing but their dress would prevent from being mistaken for German or English ladies of rank, being moreover universally blondes. On quitting Vitoria, you leave behind you the mountains and the pretty faces.

For us, however, the latter were not entirely lost. There were two in the Diligence, belonging to the daughters of a Grandee of the first class, Count de P. These youthful señoritas had taken the opportunity, rendered particularly well-timed by the revolutions and disorders of their country, of passing three years in Paris, which they employed in completing their education, and seeing the wonders of that town, soi-disant the most civilized in the world; which probably it would have been, had the old régime not been overthrown. They were now returning to Madrid, furnished with all the new ideas, and the various useful and useless accomplishments they had acquired.

Every one whose lot it may have been to undertake a journey of several days in a Diligence,—that is, in one and the same,—and who consequently recollects that trembling and anxious moment during which he has passed in review the various members of the society of which he is to be, nolens volens, a member; and the feverish interest which directed his glance of rapid scrutiny towards those in particular of the said members with whom he was to be exposed to more immediate contact, and at the mercy of whose birth and education, habits, opinions, prejudices, qualities, and propensities, his happiness and comfort were to be placed during so large and uninterrupted a period of his existence,—will comprehend my gratitude to these fair émigrées, whose lively conversation shortened the length of each day, adding to the charms of the magnificent scenery by the opportunity they afforded of a congenial interchange of impressions. Although we did not occupy the same compartment of the carriage, their party requiring the entire interior and rotonde, we always renewed acquaintance when a prolonged ascent afforded an opportunity of liberating our limbs from their confinement.

The two daily repasts also would have offered no charm, save that of the Basque cuisine,—which, although cleanly and solid, is not perfectly cordon bleu,—but for the entertaining conversation of my fair fellow-travellers, who had treasured up in their memory the best sayings and doings of Arnal, and the other Listons and Yateses of the French capital, which, seasoned with a slight Spanish accent, were indescribably piquants and original. My regret was sincere on our respective routes diverging at Burgos; for they proceeded by the direct line over the Somo sierra to Madrid, while I take the longer road by the Guadarramas, in order to visit Valladolid. I shall not consequently make acquaintance with the northern approach to Madrid, unless I return thither a second time; as to that of my fellow-travellers, I should be too fortunate were it to be renewed during my short stay in their capital.

LETTER IV.

ARRIVAL AT BURGOS. CATHEDRAL

Burgos.The chain of the Lower Pyrenees, after the ascent from the French side, and a two days' journey of alternate mountain and valley, terminates on the Spanish side at almost its highest level. A gentle descent leads to the plain of Vitoria; and, after leaving behind the fresh-looking, well-farmed environs of that town, there remains a rather monotonous day's journey across the bare plains of Castile, only varied by the passage through a gorge of about a mile in extent, called the Pass of Pancorbo, throughout which the road is flanked on either side by a perpendicular rock of from six to eight hundred feet elevation. The ancient capital of Castile is visible from a considerable distance, when approached in this direction; being easily recognised by the spires of its cathedral, and by the citadel placed on an eminence, which forms a link of a chain of hills crossing the route at this spot.

The extent of Burgos bears a very inadequate proportion to the idea formed of it by strangers, derived from its former importance and renown. It is composed of five or six narrow streets, winding round the back of an irregularly shaped colonnaded plaza. The whole occupies a narrow space, comprised between the river Arlançon, and the almost circular hill of scarcely a mile in circumference, (on which stands the citadel) and covers altogether about double the extent of Windsor Castle.

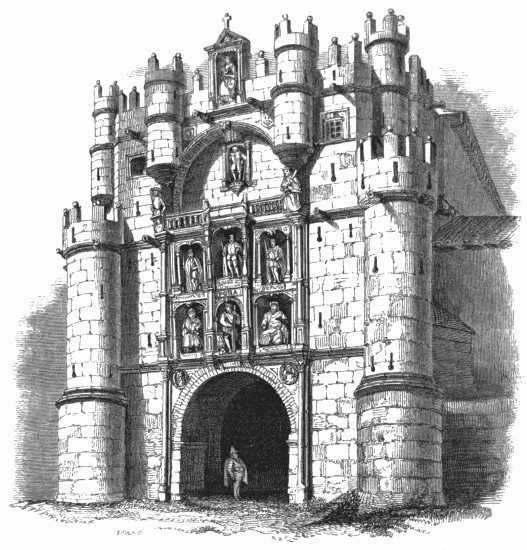

The city has received a sort of modern facing, consisting of a row of regularly built white houses, which turn their backs to the Plaza, and front the river; uniting at one extremity with an ancient gateway, which, facing the principal bridge, must originally have stood slightly in advance of the town, to which it formed a very characteristic entrance. It is a quadrangular edifice, pierced with a low semicircular arch. The arch is flanked on the river front by small circular turrets, and surmounted by seven niches, containing statues of magistrates, kings, and heroes; while over these, in a centre niche, stands a semicolossal statue of the Virgin, from which the monument derives its title of "Arco de Santa Maria." Another arch, but totally simple, situated at the other extremity of the new buildings, faces another bridge; and this, with that of Santa Maria, and a third, placed halfway between them, leading to the Plaza, form the three entrances to the city on the river side.

ARCO DE SANTA MARIA.

The dimensions of this, and many other Spanish towns, must not be adopted as a base for estimating their amount of population. Irun, at the frontier of France, stands on a little hill, the surface of which would scarcely suffice for a country-house, with its surrounding offices and gardens: it contains, nevertheless, four or five thousand inhabitants, and comprises a good-sized market-place and handsome town-hall, besides several streets. Nor does this close packing render the Spanish towns less healthy than our straggling cities, planned with a view to circulation and purity of atmosphere, although the difference of climate would seem to recommend to each of the two countries the system pursued by the other. The humidity of the atmosphere in England would be the principal obstacle to cleanliness and salubrity, had the towns a more compact mode of construction; whilst in Spain, on the contrary, this system is advantageous as a protection against the excessive power of the summer sun, which would render our wide streets—bordered by houses too low to afford complete shade—not only almost impassable, but uninhabitable.

The Plaza of Burgos (entitled "de la Constitucion," or "de Isabel II.," or "del Duque de la Victoria," or otherwise, according to the government of the day,) has always been the resort of commerce. The projecting first-floors being supported by square pillars, a sort of bazaar is formed under them, which includes all the shop population of the city, and forms an agreeable lounge during wet or too sunny weather. Throughout the remainder of the town, with the exception of the modern row of buildings above mentioned, almost all the houses are entered through Gothic doorways, surmounted by armorial bearings sculptured in stone, which, together with their ornamental inner courts and staircases, testify to their having sheltered the chivalry of Old Castile. The Cathedral, although by no means large, appears to fill half the town; and considering that, in addition to its conspicuous and inviting aspect, it is the principal remaining monument of the ancient wealth and grandeur of the province, and one of the most beautiful edifices in Europe, I will lose no time in giving you a description of it.

This edifice, or at least the greater portion of it, dates from the thirteenth century. The first stone was laid by Saint Ferdinand, on the 20th of July 1221. Ferdinand had just been proclaimed king by his mother Doña Berenguela, who had invested him with his sword at the royal convent of the Huelgas, about a mile distant from Burgos. Don Mauricio, Bishop of Burgos, blessed the armour as the youthful king girded it, and, three days subsequently to the ceremony, he united him to the Princess Beatrice, in the church of the same convent. This bishop assisted in laying the first stone of the cathedral, and presided over the construction of the entire body of the building, including half of the two principal towers.

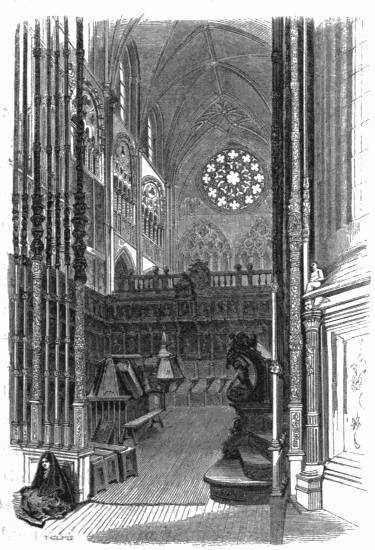

INTERIOR OF THE CHOIR.

His tomb may be seen at the back of the Choir. From the date of the building its style may at once be recognised, allowing for a difference which existed between England and the Continent, the latter being somewhat in advance. The original edifice must have been a very perfect and admirable specimen of the pointed architecture of its time in all its purity. As it is, unfortunately, (as the antiquary would say, and, I should add, the mere man of taste, were it not that tastes are various, and that the proverb says they are all in nature,) the centre of the building, forming the intersection of the transept and nave, owing to some defect in the original construction, fell in just at the period during which regular architecture began to waver, and the style called in France the "Renaissance" was making its appearance. An architect of talent, Felipe de Borgoña, hurried from Toledo, where he was employed in carving the stalls of the choir, to furnish a plan for the centre tower. He, however, only carried the work to half the height of the four cylindrical piers which support it. He was followed by several others before the termination of the work; and Juan de Herrera, the architect of the Escorial, is said to have completed it. In this design are displayed infinite talent and imagination; but the artist could not alter the taste of the age. It is more than probable that he would have kept to the pure style of his model, but for the prevailing fashion of his time. Taken by itself, the tower is, both externally and internally, admirable, from the elegance of its form, and the richness of its details; but it jars with the rest of the building.

Placing this tower in the background, we will now repair to the west front. Here nothing is required to be added, or taken away, to afford the eye a feast as perfect as grace, symmetry, grandeur, and lightness, all combined, are capable of producing. Nothing can exceed the beauty of this front taken as a whole. You have probably seen an excellent view of it in one of Roberts's annuals. The artists of Burgos complain of an alteration, made some fifty years back by the local ecclesiastical authorities, nobody knows for what reason. They caused a magnificent portal to be removed, to make way for a very simple one, totally destitute of the usual sculptured depth of arch within arch, and of the profusion of statuary, which are said to have adorned the original entrance. This, however, has not produced a bad result in the view of the whole front. Commencing by solidity and simplicity at its base, the pile only becomes ornamental at the first story, where rows of small trefoil arches are carved round the buttresses; while in the intermediate spaces are an oriel window in an ornamental arch, and two narrow double arches. The third compartment, where the towers first rise above the body of the church, offers a still richer display of ornament. The two towers are here connected by a screen, which masks the roof, raising the apparent body of the façade an additional story. This screen is very beautiful, being composed of two ogival windows in the richest style, with eight statues occupying the intervals of their lower mullions. A fourth story, equally rich, terminates the towers, on the summits of which are placed the two spires.

These are all that can be wished for the completion of such a whole. They are, I imagine, not only unmatched, but unapproached by any others, in symmetry, lightness, and beauty of design. The spire of Strasburg is the only one I am acquainted with that may be allowed to enter into the comparison. It is much larger, placed at nearly double the elevation, and looks as light as one of these; but the symmetry of its outline is defective, being uneven, and producing the effect of steps. And then it is alone, and the absence of a companion gives the façade an unfinished appearance. For these reasons I prefer the spires of Burgos. Their form is hexagonal; they are entirely hollow, and unsupported internally. The six sides are carved à jour, the design forming nine horizontal divisions, each division presenting a different ornament on each of its six sides. At the termination of these divisions, each pyramid is surrounded near the summit by a projecting gallery with balustrades. These appear to bind and keep together each airy fabric, which, everywhere transparent, looks as though it required some such restraint, to prevent its being instantaneously scattered by the winds.

On examining the interior of one of these spires, it is a subject of surprise that they could have been so constructed as to be durable. Instead of walls, you are surrounded by a succession of little balustrades, one over the other, converging towards the summit. The space enclosed is exposed to all the winds, and the thickness of the stones so slight as to have required their being bound together with iron cramps. At a distance of a mile these spires appear as transparent as nets.

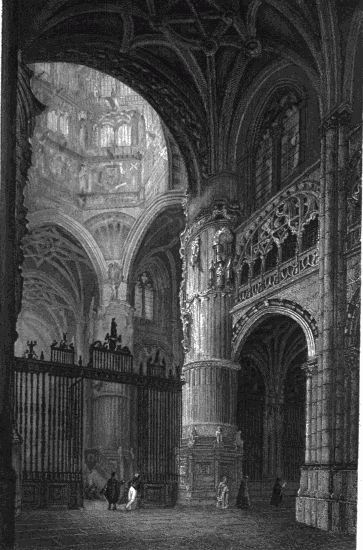

On entering the church by the western doors, the view is interrupted, as is usual in Spain, by a screen, which, crossing the principal nave at the third or fourth pillar, forms the western limit of the choir; the eastern boundary being the west side of the transept, where there is an iron railing. The space between the opposite side of the transept and the apse is the capilla mayor (chief chapel), in which is placed the high altar. There are two lower lateral naves, from east to west, and beyond them a series of chapels. The transept has no lateral naves. Some of the chapels are richly ornamented. The first or westernmost, on the north side, in particular, would be in itself a magnificent church. It is called the "Chapel of Santa Tecla." Its dimensions are ninety-six feet in length, by sixty-three in width, and sixty high. The ceiling, and different altars, are covered with a dazzling profusion of gilded sculpture. The ceiling, in particular, is entirely hidden beneath the innumerable figures and ornaments of every sort of form, although of questionable taste, which the ravings of the extravagant style, called in Spain "Churriguesco" (after the architect who brought it into fashion), could invent.

The next chapel—that of Santa Ana—is not so large, but designed in far better taste. It is Gothic, and dates from the fifteenth century. Here are some beautiful tombs, particularly that of the founder of the chapel. But the most attractive object is a picture, placed at an elevation which renders difficult the appreciation of its merits without the aid of a glass,—a Holy Family, by Andrea del Sarto. It is an admirable picture; possessing all the grace and simplicity, combined with the fineness of execution, of that artist. The chapel immediately opposite (on the south side) contains some handsome tombs, and another picture, representing the Virgin, attributed by the cicerone of the place to Michael Angelo. We next arrive at the newer part, or centre of the building, where four cylindrical piers of about twelve feet diameter, with octagonal bases, form a quadrangle, and support the centre tower, designed by Felipe de Borgoña. These pillars are connected with each other by magnificent wrought brass railings, which give entrance respectively, westward to the choir,—on the east to the sanctuary, or capilla mayor,—and north and south to the two ends of the transept. Above is seen the interior of the tower, covered with a profusion of ornament, but discordant with every other object within view.

TRANSEPT OF THE CATHEDRAL, BURGOS.

The high altar at the back of the great chapel is also the work of Herrera. It is composed of a series of rows of saints and apostles, superposed one over the other, until they reach the roof. All are placed in niches adorned with gilding, of which only partial traces remain. The material of the whole is wood. Returning to either side-nave, a few smaller chapels on the outside, and opposite them the railings of the sanctuary, conduct us to the back of the high altar, opposite which is the eastern chapel, called "of the Duke de Frias," or "Capilla del Condestable."

All this part of the edifice—I mean, from the transept eastward—is admirable, both with regard to detail and to general effect. The pillars are carved all round into niches, containing statues or groups; and the intervals between the six last, turning round the apse, are occupied by excellent designs, sculptured in a hard white stone. The subjects are, the Agony in the Garden, Jesus bearing the Cross, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, and the Ascension. The centre piece, representing the Crucifixion, is the most striking. The upper part contains the three sufferers in front; and in the background a variety of buildings, trees, and other smaller objects, supposed to be at a great distance. In the foreground of the lower part are seen the officers and soldiers employed in the execution; a group of females, with St. John supporting the Virgin, and a few spectators. The costumes, the expression, the symmetry of the figures, all contribute to the excellence of this piece of sculpture. It would be difficult to surpass the exquisite grace displayed in the attitudes, and flow of the drapery, of the female group; and the Herculean limbs of the right-hand robber, as he writhes in his torments, and seems ready to snap the cords which retain his feet and arms,—the figure projecting in its entire contour from the surface of the background,—present an admirable model of corporeal expression and anatomical detail.