Continental Monthly , Vol. 5, No. 6, June, 1864

The Mississippi proper rises in the State of Minnesota, about 47° and some minutes north latitude, and 94° 54' longitude west, at an elevation of sixteen hundred and eighty feet above the level of the Gulf of Mexico, and distant from it two thousand eight hundred and ninety-six miles, its utmost length, upon the summit of Hauteurs de Terre, the dividing ridge between the rivulets confluent to itself and those to the Red River of the North. Its first appearance is a tiny pool, fed by waters trickling from the neighboring hills. The surplus waters of this little pool are discharged by a small brook, threading its way among a multitude of very small lakes, until it gathers sufficient water, and soon forms a larger lake. From here a second rivulet, impelled along a rapid declination, rushes with violent impetuosity for some miles, and subsides in Lake Itasca. Thence, with a more regular motion, until it reaches Lake Cass, from whence taking a mainly southeasterly course, a distance of nearly seven hundred miles, it reaches the Falls of St. Anthony. Here the river makes in a few miles a descent of sixteen feet. From this point to the Gulf, navigation is without further interruption, and the wonders of the Mississippi begin.

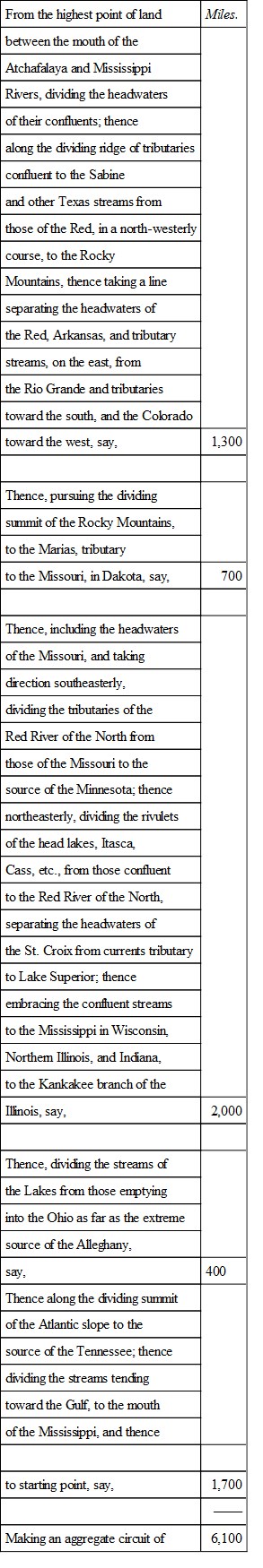

It is not possible to give, with complete exactness, the outlines of the immense valley drained by the Mississippi, yet, with the assistance of accurate surveys, we can make an approximation, to say the least, which will convey some idea of the physical necessity of the river to the vast area through the centre of which it takes its course.

We will say:

Within this extensive limit we find, from surveys, the following aggregate area in square miles, estimated by valleys:

As a natural consequence of the drainage of this immense area, the Mississippi receives into its waters a large amount of suspended earthy matter. This, however, does not very strikingly appear on the upper river, its own banks and those of its tributaries being more of a gravelly character and less friable than lower down. The gravity of particles, therefore, worn from the bed and sides of the channel above, unless the current be exceedingly strong, is greater than the buoyant capacity of the water, and falls to the bottom, along which, sometimes, it is forced by the abrasion of the water, until it meets some obstruction, which gathers the particles into shoal formations. This fact causes much inconvenience in the navigation of the upper rivers.

It is not until we reach the confluence of the streams of Southern Illinois and Missouri, that the sediment of the river becomes striking. Those streams, freighted with the rich loam and vegetable matter of the prairies of the east and west, soon change entirely the appearance of the Mississippi. Above the Missouri, the river is but slightly tinged; and indeed, after that great current enters, for some distance the two run side by side in the same channel, and yet are divided by a very distinct line of demarcation. It is only after the frequent sinuosities of the channel, that the two waters are thrown into each other and fairly blend. The sedimentary condition of the Missouri is so great that drift floating upon its muddy surface, by accretion becomes so heavily laden with earthy matter that it sinks to the bottom. This precipitation of drift has taken place to such an extent, that the bed of the Missouri is in many places completely covered to a great depth by immense fields of logs. Of all the silt thrown into the Mississippi, the Missouri furnishes about one third.

After receiving the Missouri, next enters the Ohio. The water of this river is less impregnated than the Missouri, though not by any means free from silt. The country through which it flows is mountainous, and the soil hard, and does not afford the same facility of abrasive action as that of the other rivers.

From the mouth of the Ohio, the Mississippi pursues a course of nearly four hundred miles, when it receives the turbid waters of the White and Arkansas Rivers. In the intervening distance a large number of small currents, more or less largely sedimentary, according to the character of the country through which they run, enter the Mississippi, in the aggregate adding materially to the sediment of the receiving stream. The White and Arkansas carry in their waters a large amount of unprecipitated matter. In this vicinity, too, sets in that singular system of natural safeguards of the surrounding country, the bayous. The country here also changes its appearance, becoming flat and swampy, and in some parts attaining but a few feet above the flood of the river, whereas in other parts, as we approach the Gulf, the country is even lower than the river.

The miasmatic and poisonous water of the Yazoo next enters, about ten miles above Vicksburg. This river is more deeply impregnated with a certain kind of impurities than any other tributary of the Mississippi. The waters are green and slimy, and almost sticky with vegetable and animal decomposition. During the hot season the water is certain disease, if taken into the stomach. The name is of Indian origin, and signifies 'River of Death.' The Yazoo receives its supply from bayous and swamps, though it has several considerable tributaries.

Below the Yazoo, on the west side, enters the Red. The name indicates the peculiar caste of its water. This river carries with it the washings of an extensive area of prairies and swamps, and is the last of the great tributaries. Hence the tendency of streams is directly to the Gulf, and that network of lateral branches, of which we will hereafter speak, begins.

We have only considered the most prominent tributaries: the sediment also brought down by the numerous smaller streams is very great, and makes great additions to the immense buoyant matter of the Mississippi.

The river itself from its own banks scours the larger portion of the sediment it contains; and in so gigantic a scale is this carried on, that it can be seen without the exercise of any very remarkable powers of sight. It is not by the imperceptible degrees usually at work in other streams, but often involves in its execution many acres of adjoining land. It will be interesting to consider this more fully.

By a curious freak of nature, the tendency of the channel of the Mississippi is always toward one or the other of its banks, being influenced by the direction of its bends. The principle is one of nicely regulated refraction. If the river were perfectly straight, the gravity and inertia of its waters would move in a right line, with a velocity beyond all control. But we find the river very sinuous, and the momentum of current consequently lessened. For example, striking in an arm of the river, by the inertia of the moving volume, the water is thrown, and with less velocity, upon the opposite bank, which it pursues until it meets another repellent obstacle, from which it refracts, taking direction again for the other side. Above the Missouri, the river is principally directed by the natural trough of the valley. Below this, however, the channel is purely the work of the river itself, shaped according to the necessities of sudden changes or obstructions. This is proven by the large number of old and dry beds of the river frequently met with, the channel having been diverted in a new direction by the accumulation of sediment and drift which it had not the momentum to force out.

Where the gravity of the greatest volume and momentum of water falls upon the bed of the river, there is described the thread of the channel, and all submerged space outside of this, though in the river, acts as a kind of reservoir, where eddies the surplus water until taken up by the current. And it always happens, where the channel takes one bend of the bed, a corresponding tongue of shallow water faces the indenture. Where the river, by some inexplicable cause, has been thrown from its regular channel, or its volume of water embarrassed by some difficulties along the banks, the effect is immediately perceived upon the neighboring bank. The column of water thus impinged against it at once acts upon the bank, and, singularly enough, exerts its strongest abrasive action at the bottom, undermining the bank, which soon gives way, and instead of toppling forward, it noiselessly slides beneath the water and disappears. Acres of land have thus been carried away in an incredibly short time, and without the slightest disruption of the serene flow of the mighty current.

This carrying away of the banks, immense as is the amount of earth thrown into the waters of the river, has no sensible effect in blocking or directing the current, though it imperceptibly raises the channel. The force of the water does not permit its entire settlement in quantities at any one place, but distributes it along the bottom and shores below. Were this not the case, it is easily to be seen, the abrasion of the river banks would be greatly increased, and the destruction of the bordering lands immense.

A singular feature resulting from the above may here be mentioned. By pursuing the course of the river, a short distance below, on the opposite bank, it will be seen that a large quantity of the earth introduced into the current by the falling of the banks, has been thrown up in large masses, forming new land, which, in a few seasons, becomes arable. That which is not thus deposited, as already stated, is transported below, dropping here and there on the way, until what is left reaches the Gulf, and is precipitated upon the 'bars' and 'delta,' at the mouth. It not unfrequently happens that planters along the river find themselves suddenly deprived of some of their acres, while one almost opposite finds himself as unexpectedly blessed with a bountiful increase of his domain.

From causes almost similar to those given to explain the sudden and disastrous changes of the channel of the river, are also produced those singular shortenings, known as 'cut-offs,' which are so frequently met with on the Mississippi. At a certain point the force of the current is turned out of its path and impinged against a neck of land, that has, after years of resistance, been worn down to an exceedingly small breadth. Possibly the river has merely worn an arm in its side, leaving an extensive bulge standing out in the river, and connected with the mainland by an isthmus. The river striking in this arm, and not having sufficient scope to rebound toward the other bank, is thrown into a rotary motion, forming almost a whirlpool. The action of this motion upon the banks soon reduces the connecting neck, which separates and blocks the waters, until, at last, no longer able to cope with the great weight resting against it, it gives way, and the river divides itself between this new and the old channel.

Nor do these remarkable instances of abrasive action constitute the entire washing from the banks. The whole length of the river is subject to a continual deposit and taking up of the silt, according to the buoyant capacity of the water. This, too, is so well regulated that the quantity of earthy matter held in solution is very nearly the same, being proportioned to the force of the current. For instance, if the river receive more earth than it can sustain, the surplus sediment drops upon the bottom or is forced up upon the sides. If the river be subject to a rise, a proportionate quantity of the dropped sediment is again taken up, and carried along or deposited again, according to the capacity of the water. By this means a well-established average of silt is at all times found buoyant in the river.

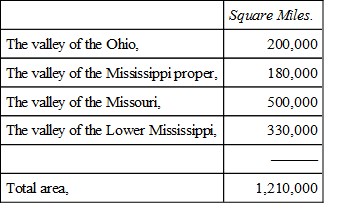

Having briefly examined the sedimentary character of the Mississippi, some investigations as to the proportion of sediment to water may be of interest. And it is well to state here that a mean stage of flow is taken as the basis upon which to start the experiments. The experiments and analysis of the water were made by Professor Riddell, at intervals of three days, from May 21st to August 13, 1846, and reported to the Association of American Geologists and Naturalists.

The water was taken in a pail from the river in front of the city of New Orleans, where the current is rather swift. That portion of the river contains a fair average of sedimentary matter, and it is sufficiently distant from the embouchure of the last principal tributary to allow its water to mix well with that of the Mississippi.

'The temperature,' says the Professor, 'was observed at the time, and the height of the river determined. Some minutes after, the pail of water was agitated, and two samples of one pint each measured out. The measure graduated by weighing at 60 degrees Fahrenheit 7,295.581 grains of distilled water. After standing a day or two, the matter mechanically suspended would subside to the bottom. Nearly two thirds of the clear supernatant liquid was next decanted, while the remaining water, along with the sediment, was in each instance poured upon a double filter, the two parts of which had previously been agitated, to be of equal weight. The filters were numbered and laid aside, and ultimately dried in the sunshine, under like circumstances, in two parcels, one embracing the experiments from May 22 to July 15, the other from July 17 to August 13. The difference in weight between the two parts of each double filter was then carefully ascertained, and as to the inner filter alone the sediment was attached, its excess of weight indicated the amount of sediment.'

As the table may be interesting, showing the height and temperature of the water as well as the result of the experiments at the different times, we introduce it complete:

Table showing the Quantity of Sediment contained in the Water of the Mississippi River

The mean average of column A. is 6.32.

The mean average of column B. is 6.30.

Transcriber's Note: Data in the above table is as in the original.

'By comparison with distilled water,' says the same, 'the specific gravity of the filtered river water we found to be 1.823; pint of such water at 60° weighs 7,297.40.' Engineer Forehay says the sediment is 1 to 1,800 by weight, or 1 in 3,000 by volume.

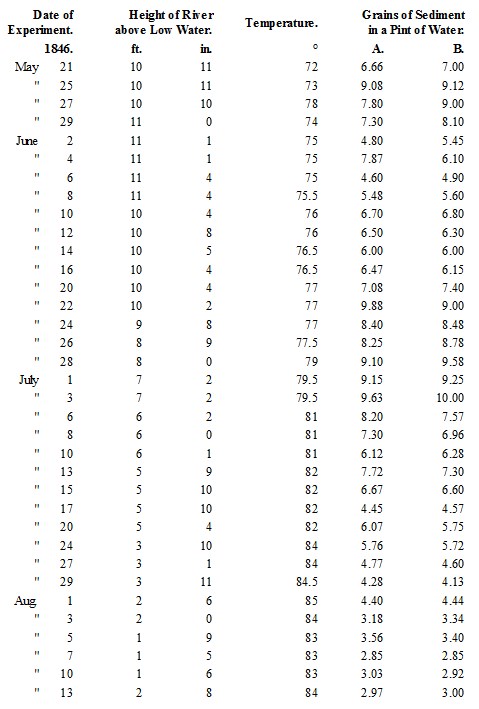

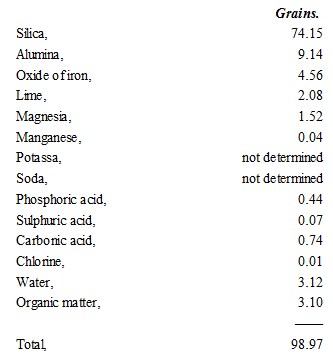

Professor Riddell also comes to the following conclusions, after an analytic investigation of the sediment. He took one hundred grains from the river margin, dried it at 212° Fahrenheit, before weighing, and found it to contain:

The existence of so large a quantity of sediment in the water of the Mississippi, leads to divers formations in its bed. These formations are principally 'bars' and 'battures.' The banks are also much affected.

When the water of the river, aided by the current, has attained its full capacity of buoyant earth, as we have already said, the excess falls to the bottom. Instead, however, of remaining permanently where it first lodged, which would soon fill up the channel and cause the river to overflow, the scouring of the water on the bottom forces a large portion along with the current, though it be not suspended. Pursuing its course for a while, some irregularity or obstruction falls in the way—a sunken log, perhaps. This obstacle checks the progress of the moving earth—it accumulates; the next wave brings down more—the accumulation becomes greater; until, in the course of a few years, there is a vast field of deposit, and a 'bar' is formed. These 'bars' often divert the channel, and occasion the immense washings before alluded to.

Bars are generally found close to the banks, though there are examples in which they extend in a transverse direction to the current. Bars of this kind very much embarrass and endanger navigation in low water. At Helena, Arkansas, there is an instance of a transverse bar, upon which, in October, the water is less than six feet. These bars are formed of sand, which seems to have been the heavier and less buoyant of the components of the earth thrown into the current by abrasion, the lighter portions having been separated by the water and carried off.

It will not be necessary to consider further the subject of bars in the river, but those at its mouth deserve some attention. The subject is one that has led to much theorizing, study, and fear—the latter particularly, from an ill-founded supposition that they threaten to cut off navigation into the Gulf.

Near its entrance into the Gulf, the Mississippi distributes its waters through five outlets, termed passes, and consequently has as many mouths. These are termed Pass à l'Outre, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Southwest. They differ in length, ranging from three to nine miles. They also all afford sufficient depth of water for commercial purposes, except at their mouths, which are obstructed by bars. The depth of water upon one of these is sufficient to pass large vessels; a second, vessels of less size; and the rest are not navigable at all, as regards sea-going vessels. These bars, too, are continually changing, according to the winds or the currents of the river. It is a rather singular fact that when one of the navigable passes becomes blocked, the river is certain to force a channel of navigable depth through one of the others, previously not in use; so that at no one time are all the passes closed.

In looking into the past, and noticing the changes, it is recorded that in 1720, of all the passes the South Pass was the only one navigable. In 1730, there was a depth of from twelve to fifteen feet, according to the winds, and at another time even seventeen feet was known. In 1804, upon the statement of Major Stoddard, written at that date, the East Pass, called the Balize, had then about seventeen feet of water on the bar, and was the one usually navigated. The South Pass was formerly of equal depth, but was then gradually filling up. (This pass, at present, 1864, is not at all navigated.) The Southwest Pass had from eleven to twelve feet of water. The Northeast and Southeast Passes were traversed only by small craft. Since 1830 the Southwest Pass has been gaining depth. This and Pass à l'Outre are now the only two out of the five of sufficient depth to admit the crossing of the larger class of vessels. The former, however, is the one in most general use. All the other passes, with the exception of the two mentioned, have been abandoned.

In regard to the changes and numerous singular formations at the mouths of the Mississippi, we give a statement made by William Talbot, for twenty-five years a resident of the Balize. He says:

'The bars at the various passes change very often. The channel sometimes changes two and three times in a season. Occasionally one gale of wind will change the channel. The bars make to the seaward every year. The Southwest Pass is now the main outlet used. It has been so only for three years, as at that time there was as much water in the Northeast Pass as in it. The Southeast Pass was the main ship channel twenty years ago; there is only about six feet of water in that pass now; and where it was deepest then, there are only a few inches of water at this time. The visible shores of the river have made out into the Gulf two or three miles within my memory. Besides the deposits of mud and sand, which form the bars, there frequently rise up bumps, or mounds, near the channel, which divert its course. These bumps are supposed to be the production of salt springs, and sometimes are formed in a very few days. They sometimes rise four or five feet above the surface of the water.' He 'knew one instance when some bricks, that were thrown overboard from a vessel outside the bar, in three fathoms of water, were raised above the surface by one of these banks, and were taken to the Balize, and used in building chimneys. In another instance, an anchor, which was lost from a vessel, was lifted out of the water, so that it was taken ashore. About twenty years ago, a sloop, used as a lighter, was lost outside the bar in a gale of wind; several years afterward she was raised by one of these strange formations, and her cargo was taken out of her.'

We may say the bumps of which Mr. Talbot speaks are termed 'mud bumps,' from the fact of being composed of sediment. They present a curious spectacle as seen from a passing steamer. They are undoubtedly the result of subterranean pressure, but from what cause, whether volcanic, or the influence of the sea or river, or both, has not been determined. Many speculations have been entered into in regard to these phenomena, but as yet without fruitful result.

Leaving this digression, we proceed to notice that the theories set up to explain the causes of the bars at the mouth of the river, have been numerous and various. Some suppose them to be the result of the water of the river meeting the opposing force of the Gulf waves, checking the current, and causing a precipitation of the suspended sediment. Others are of the opinion that the bars are entirely the effect of marine action, and endeavor to show that the immense inward flow of the Gulf washes up from its bed the vast accumulations that are continually forming in the way of navigation.

After a personal observation and investigation, and as well after frequent and free consultation with others, we are persuaded to discredit the above-mentioned theories. The resistance of the Gulf does not form the bars, though it exerts an influence. The immense volume and force of water ejected from the river receives no immediate repellent action from the Gulf, but extends into it many miles without the least signs of disturbance, as may be plainly discovered even in the most casual observation. It is known as well that the water of the river remains perfectly palatable at a very close proximity to the sea. This is a very good evidence of the superior force of the river's current. The two volumes of water mix a considerable distance out at sea.

An able engineer states that, upon examination, he found a column of fresh water seven feet deep and seven thousand feet wide, and discovered salt water at eight feet below the surface. As the result of his investigations, he divides the water into three strata, as follows:

1. Fresh water, running out at the top with a velocity of three miles an hour.

2. Salt water, beneath the fresh, also running out at about the same velocity.

3. A reflex flow of salt water, running in slowly at the bottom.

It is this inward current, he thinks, that produces the deposit, and in doing so carries with it no small degree of sea drift. The influx of the lower column flowing up stream, after it passes the dead point, is allowed time and opportunity for the sediment to deposit. The principle of the reflex current is somewhat that of an eddy, not only produced by the conflict of two opposing bodies of water, but also is much influenced in the under currents by the multitude of estuaries presented by the irregular sea front of the coast.

A gentleman, who seems to have taken a very statistical view of these bars, makes the following business-like and curious calculation as to their immensity: we introduce it on account of its originality. He says the average quantity of water discharged per second is five hundred and ten thousand cubic feet. The quantity of salt suspended, one in three thousand by volume. The quantity of mud discharged, one hundred and seventy cubic feet per second. Considering seventeen cubic feet equal to one ton, the daily discharge of mud is eight hundred and sixty-four thousand tons, and would require a fleet of seventeen hundred and twenty-eight ships, of five hundred tons each, to transport the average daily discharge. And to lift this immense quantity of matter, it would require about seven hundred and seventy-one dredging machines, sixteen horse power, with a capacity of labor amounting to one hundred and forty tons, working eight hours.

Another class of sedimentary formations met with along the banks of the Mississippi are the battures. There is one remarkable instance of these in front of New Orleans, which has led to much private dispute, and even public disturbance, as to ownership. Within sixty years, in front of the Second Municipality of the city, the amount of alluvial formations susceptible of private ownership were worth over five millions of dollars, that is, nearly one hundred thousand dollars per annum, and the causes which have produced them are still at work, and will probably remain so. As far back as 1847 these remarks were made upon the subject: 'The value of the annual alluvial deposits in front of the Second Municipality now is not less than two hundred thousand dollars, and, with the exception of the batture between the Faubourg St. Mary line and Lacourse street, all belongs to this municipality.' 'Such a source of wealth was never possessed by any city before. In truth, it may be said that nature is our taxgatherer, levying by her immutable laws tribute from the banks of rivers and from the summits of mountains thousands of miles distant to enrich, improve, and adorn our favored city.' There are numerous other examples of the kind going on elsewhere along the river.