One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

David Redfern/Getty Images

As the tour progressed, the Beatles’ popularity grew and grew, while Helen’s went into decline. By chance, both the Beatles and Helen had released new singles at roughly the same time – ‘Please Please Me’ on 17 January, ‘Queen for Tonight’ on 26 January. As the weeks went by, the status of the famous headliner and the lowly support act switched places. At the beginning of February ‘Please Please Me’ was at number 33, and ‘Queen for Tonight’ was nowhere to be seen. By 6 February ‘Please Please Me’ was number 16, and ‘Queen for Tonight’ was still nowhere to be seen. On 13 February ‘Queen for Tonight’ scraped in at 42, while ‘Please Please Me’ was number 3. By 23 February ‘Please Please Me’ was number 2 and ‘Queen for Tonight’ was 33, the highest position it would ever reach: the following week it had slipped to 35. Helen was only sixteen years old, and on the skids: ‘I’d been a novelty at fourteen but I suffered from the Shirley Temple syndrome. I’d grown up. Suddenly I was beginning to look a little bit passé in spite of topping the bill.’

One day, reading a music paper on the tour coach, she saw the headline ‘Is Helen Shapiro a “Has-Been” at 16?’ ‘I felt just as if somebody had punched me in the stomach.’ In the seat behind her, John Lennon, six years her senior, noticed that she was upset.They had always had a good relationship: like many girls her age, she had a crush on him. He in turn was uncharacteristically protective of her, treating her, in Helen’s words, ‘like some kind of kid sister’.

‘What’s up, Helly?’

She showed him the offending headline. John sought to reassure her. ‘You don’t want to be bothered with that rubbish. You’re all right. You’ll be going on for years.’

But no amount of reassurance could disguise the truth. Helen Shapiro was to look back on that moment as ‘one of those milestones I would pinpoint as the beginning of change; not just for me but for a lot of solo singers. The Beatles were the beginning of a new era, a new wave of groups, the whole Merseyside thing.’

By the end of February, the Beatles had been promoted above Danny Williams on the tour, charged with closing the first half of the programme. For the first time, their music was being drowned out by screams. Helen continued to travel on the coach with the support acts, but, ever conscious of the Beatles’ burgeoning star status, Brian Epstein made them travel in their own car, away from the others. They left the tour before the end, off to head their own shows. Helen missed the Beatles: ‘Things were never quite the same afterwards.’

After the tour, she continued to record. ‘My records were getting better, yet the sales were worse. All during ’63 the whole Merseyside thing was growing and growing. London was out, along with solo artistes. The writing was on the wall for anyone who didn’t belong to a group, preferably with drums, and lead, bass and rhythm guitars.’

Her next record, ‘Woe is Me’, peaked at number 35. By October 1963, when she came to release ‘Look Who it Is’, the Beatles had become the most famous act in Britain: ‘She Loves You’ was at number 1, and well on its way to selling a million copies.

To help Helen promote her single, the producer of Ready Steady Go! suggested she be filmed singing it to the Beatles, who were headlining. It was agreed that she would sing a verse to each Beatle in turn, but as there were only three verses, one of them had to stand aside. They tossed a coin, and the loser was Paul, who went off to a neighbouring studio, where he was charged with picking the winner of a competition in which four girls mimed to ‘Let’s Jump the Broomstick’ by Brenda Lee.

Paul decided that the winner was girl number four, Melanie Coe, aged fourteen, from Stamford Hill in London.

1 Who later changed his name to Marc Bolan.

25

On previous shows, the prize had been a date with a pop star, but this time it was just the Beatles’ LP, Please Please Me. Upon hearing this, Melanie Coe’s face fell. ‘I thought I was going to have a dinner date with the Beatles, so I was terribly disappointed.’ Moreover, Paul McCartney’s firm handshake caused her false nails to come loose. ‘I don’t think I’d ever worn them before, and I wanted to have everything perfect.’ But her disappointment was assuaged when the producers, impressed by her natural exuberance, offered her a year’s stint as a background dancer, which let her rub shoulders with stars like Stevie Wonder, Dusty Springfield, Cilla Black and Freddie and the Dreamers.

Had she not been picked out by Paul McCartney, might Melanie Coe have been more content with the life of a schoolgirl? Instead she grew restless, and as time went by she started venturing into central London, against her parents’ wishes. ‘In 1964, I’d say there were three or four discos in London, so you were likely to meet the same people wherever you went.’

On one of these secret excursions she went with a friend from Hamburg to the Bag o’ Nails Club in Kingly Street, just off Carnaby Street. As in the Beatles song, she was just seventeen. Her friend had long boasted that she knew the Beatles very well, but Melanie didn’t believe her. ‘We were sitting down having a drink and in walks John Lennon with his entourage. And she waves to him and he comes over to us. “It’s you! Come join us!” And before I knew it, I’m seventeen and I’m at a table with John Lennon! That’s how it was!’

Touched by these two encounters, the first with Paul, the second with John, what young girl could have resisted the lure of adult life? Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before Melanie became pregnant. One afternoon she left a note on the kitchen table that she hoped would say more, and left home, off to live with a croupier in Bayswater.

Melanie had been away from home for a week when on 27 February 1967 she saw her picture in the Daily Mail, alongside a headline saying:

‘A-Level Girl Dumps Car and Vanishes’

On that same day, Paul McCartney also happened to be reading the Daily Mail, and his eye was caught by the same headline. The report began:

The father of 17-year-old Melanie Coe, the schoolgirl who seemed to have everything, spent yesterday searching for her in London and Brighton.

Melanie had her own car, an Austin 1100. It was left unlocked outside her home when she vanished.

She had a wardrobe full of clothes. She took only what she was wearing – a cinnamon trouser suit and black patent leather shoes.

She left her chequebook and drew no money from her account.

Melanie, who has blonde hair and is 5ft 1inch tall, was studying for her A-level examinations. She planned to go to university or drama school.

‘I cannot imagine why she should run away,’ her father told reporters. ‘She has everything here. She is very keen on clothes, but she left them all, even her fur coat.’

Without realising that Melanie was the very same girl he had picked to win a prize over three years before, Paul was inspired to write ‘She’s Leaving Home’.

‘I started to get the lyrics: she slips out and leaves a note and then the parents wake up and then … It was rather poignant,’ he recalled. ‘… and when I showed it to John, he added the Greek chorus, long sustained notes, and one of the nice things about the structure of the song is that it stays on those chords endlessly.’

John found the Greek chorus – ‘Sacrificed most of our lives’, ‘We gave her everything money could buy’ – simple to write: these were the very same complaints he had heard so often from the lips of his Aunt Mimi.

The Beatles recorded ‘She’s Leaving Home’ on the evening of 17 March 1967. By this time Melanie Coe was back home with her parents, who had managed to track her down. She first heard the song soon after it came out on the Sgt. Pepper album at the end of May. ‘I didn’t realise it was about me, but I remember thinking it could have been about me. I found the song extremely sad. It obviously struck a chord somewhere. It wasn’t until later, when I was in my twenties, that my mother said, “You know, that song was about you.”’ She had seen an interview with Paul on television and he said he’d based the song on this newspaper article. She put two and two together.

‘The most interesting thing in the song is what the father said: “We gave her everything money could buy.” And in the newspaper article, my father actually says almost those words. He doesn’t understand why I would have left home when they bought me or gave me everything. Which is true; they had bought me a car and they always bought me expensive clothes and things like that. But, as we know, that doesn’t mean that you get on well with your parents, or even love them, just because they buy you material things.’

Quite by chance, McCartney had hit another nail on the head: before starting work as a croupier, her older boyfriend had worked in the motor trade.1

1 The following year Melanie left home again, having married a Spaniard. They broke up after a year, and then she moved to California, intent on pursuing a career in acting and dancing. She enjoyed a brief romance with Burt Ward, the actor who played Batman’s young sidekick Robin in the TV series. In 1981 she returned home to look after her mother, who was dying.

26

The Beatles started 1963 playing modest gigs such as the Wolverham Welfare Association dance at the Civic Hall in Wirral (14 January) and a Baptist church youth club party at the Co-Operative Hall in Darwen (25 January). On 4 April, well into spring, they performed an afternoon concert for the boys of Stowe School in Buckinghamshire.

But their popularity was speedily growing. In March their second single, ‘Please Please Me’, had only been prevented from reaching number 1 in the UK charts by the continued popularity of Frank Ifield’s ‘Wayward Wind’ and, latterly, Cliff Richard’s ‘Summer Holiday’. But in May ‘From Me to You’ became their first single to reach number 1, and their debut album, Please Please Me, also went to number 1, where it was set to remain for the next thirty weeks.

By the end of that month, they had appeared for a second time on national television, singing ‘From Me to You’ on the children’s programme Pops and Lenny, accompanied by Lenny the Lion, the distinguished glove puppet. Furthermore, they had been given a new radio series on the BBC, Pop Go the Beatles. The corporation’s Audience Research Department estimated that 5.3 per cent of the population, or 2.8 million people, had listened to the first episode, with audience comments ranging from ‘an obnoxious noise’ to ‘really with-it’.

But fame comes with drawbacks. Paul had originally planned to celebrate his twenty-first birthday at the McCartney family home in Forthlin Road, but it soon became clear that fans might prove a hazard. So the McCartneys switched the party to his Auntie Jin’s house, across the Mersey in Huyton, where there was plenty of room for a marquee in the large back garden, and privacy was assured.

The birthday party took place on 21 June 1963. Guests included the three other Beatles, John’s wife Cynthia, Paul’s brother Mike, Mike’s two friends Roger McGough and John Gorman, John’s friend Pete Shotton, Ringo’s girlfriend Maureen, the disc jockey Bob Wooler, Gerry Marsden, Billy J. Kramer and any number of musicians. Paul was particularly delighted when the Shadows came through the door. ‘I can’t believe it,’ he said to Tony Bramwell, who worked for Brian Epstein. He then thought about it for a second, before adding, ‘But we’re sort of like one of them now, aren’t we?’

‘Yeah, only bigger,’ replied Bramwell, who remembered Paul giving him a doubtful look, ‘as if I was pulling his leg’.

Paul’s new girlfriend, the seventeen-year-old actress Jane Asher, was also there. They had first met two months before. Cynthia was very taken with her: ‘She was beautiful, with auburn hair and green eyes. Also, although she had been a successful actress since she was five, she was unaffected, easy to talk to and friendly.’

Paul’s dad Jim played old-fashioned numbers on his piano, and, later, the up-and-coming band the Fourmost took to a makeshift stage. Their bass player Billy Hatton had struck the deal. ‘Paul offered to pay us the usual rate for this kind of job, but as we were going to the party anyway, we said we would do it for just one and fourpence halfpenny each.’

As the party progressed, Pete Shotton spotted John in a corner, ‘nursing a Scotch and Coke and looking glum as could be’. John seemed pleased to see Pete, and together they drifted into the garden. Over more drinks, John enjoyed pointing out the various pop stars present. ‘Cliff Richard might even show up tonight,’ he added, before going off to get yet another refill.

Pete set off to find a loo. On his return, everything had changed. ‘When I emerged from the WC … the party seemed to have been somehow transformed from a celebration to a wake. Something, obviously, had gone terribly wrong.’

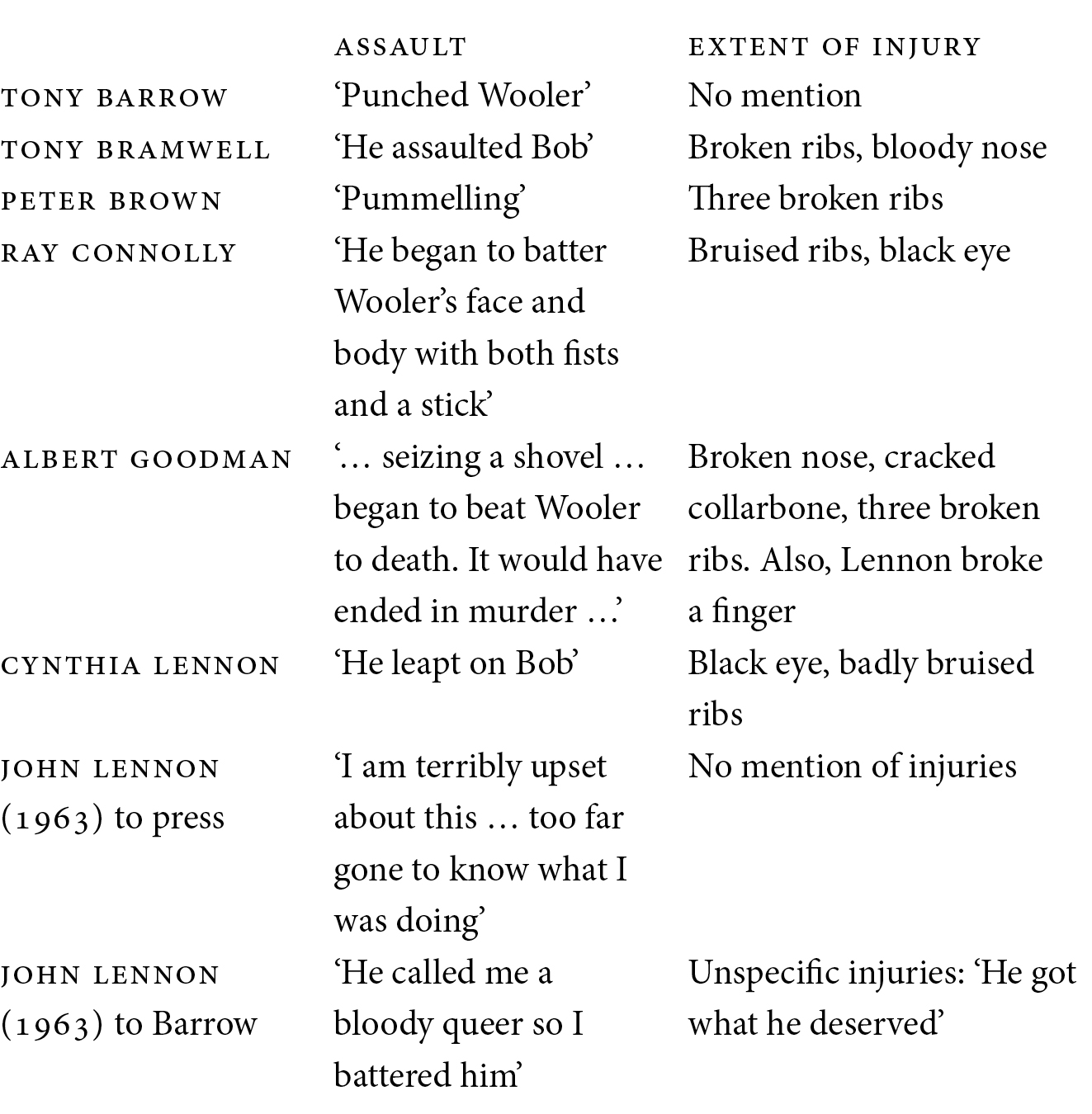

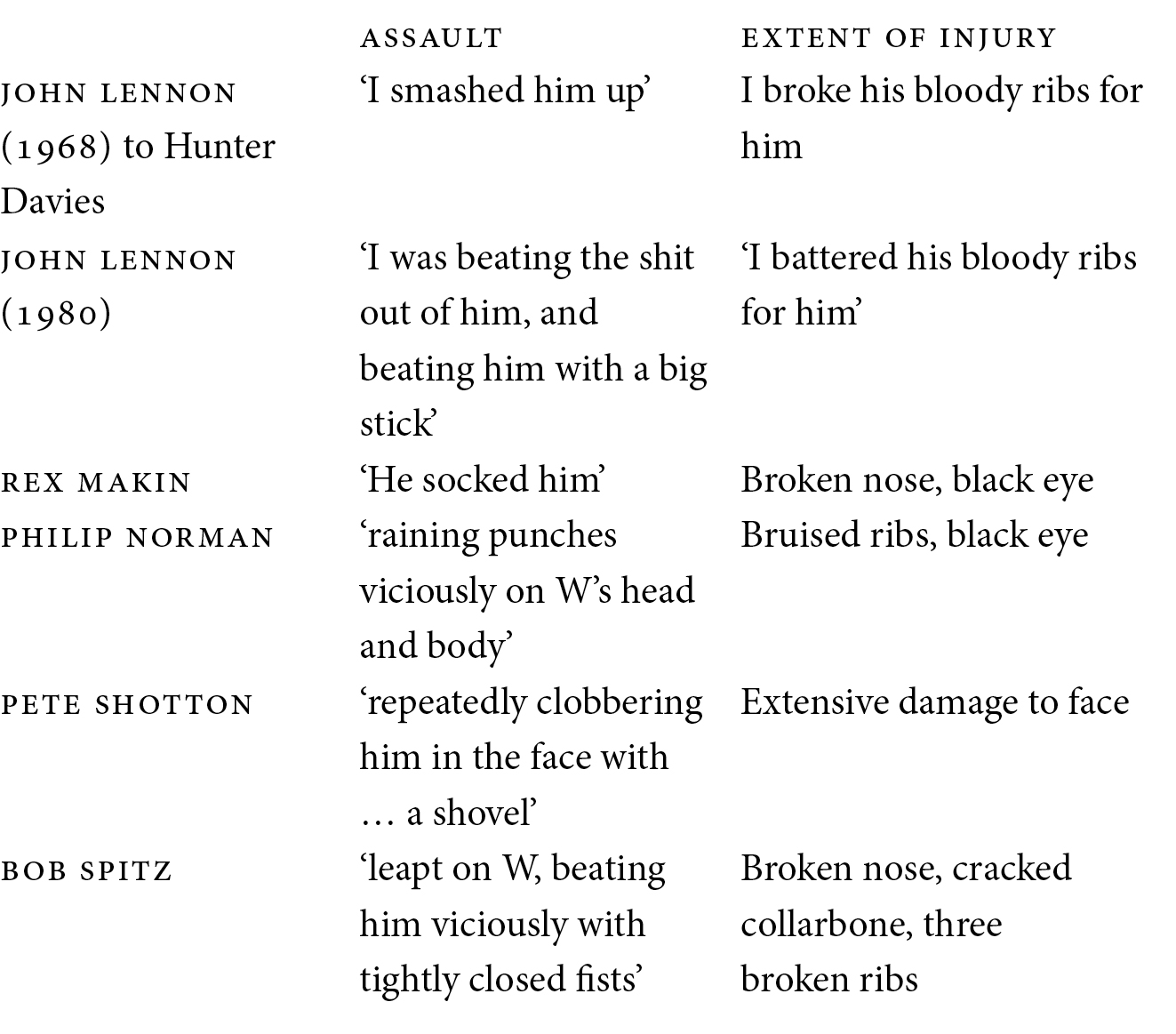

Bob Wooler, the Cavern MC, was lying on the floor, with blood everywhere. Apparently he had been teasing John about his recent holiday in Spain with Brian Epstein, and John had taken his revenge. ‘A well-drunk John punched Wooler for taunting him,’ recalled Tony Barrow in his autobiography. Another of Epstein’s assistants, Peter Brown, added more detail, saying that ‘in a mad rage and obviously very drunk’, John had started ‘pummelling’ an unnamed guest; it had taken ‘three men to pull John off, but not before he managed to break three of the man’s ribs’.

Tony Bramwell remembered that ‘John saw red. He assaulted Bob, breaking his ribs and ending up with a bloody nose himself.’ Shotton took it a step further: ‘John responded by knocking Bob to the ground and repeatedly clobbering him in the face with, I believe, a shovel. The damage to Bob’s visage was so extensive that an ambulance had to be summoned to rush him to hospital.’

In her second autobiography, written forty-two years after the event (she failed to mention the incident in her first), Cynthia Lennon wrote: ‘John, who’d had plenty to drink, exploded. He leapt on Bob, and by the time he was dragged off Bob had a black eye and badly bruised ribs. I took John home as fast as I could and Brian drove Bob to hospital.’ Cynthia claimed to remember John telling her, ‘He called me a queer.’ Others, though, have suggested Wooler said something more insidious, like, ‘Come on, John. Tell us about you and Brian in Spain. We all know.’

Thirty-six years later, Rex Makin, the Epstein family’s solicitor,1 gave an account in which he deftly avoided mentioning Brian Epstein or the Spanish holiday, and suggested that Wooler had come on to John: ‘Everybody had a lot to drink and John Lennon thought or perceived that Wooler had made a pass at him, whereupon he socked him and broke his nose and gave him a black eye.’

The Beatles’ biographers also offer radically different versions of the same event. Hunter Davies, who gave Epstein and the Beatles copy approval for his authorised 1968 biography, wrote that ‘John picked a fight with a local disk [sic] jockey,’ and quoted John saying, ‘I broke his bloody ribs for him. I was pissed at the time. He called me a queer.’

Other biographers have tended to take it a stage further. ‘Without warning, John exploded,’ wrote Ray Connolly. ‘Lashing out, he began to batter Wooler’s face and body with both his fists and a stick … He went berserk, to the extent that when he was pulled off Wooler, the inoffensive and much older man had to be quickly driven to hospital by Brian, where he was treated for bruised ribs and a black eye.’

In his 1981 biography of the Beatles, Shout!, Philip Norman described the party as ‘a typical Liverpool booze-up, riotous and noisy’. He mentioned that ‘John Lennon got into a fight with another guest,’ but didn’t say who it was, or what the fight was about. Norman was more forthcoming in his 2016 biography of Paul, disagreeing with Connolly that Wooler was inoffensive, and instead describing him as ‘notoriously sharp-tongued’. In his account of the fight, Norman had John ‘raining punches viciously on Wooler’s head and body’, but offered no assessment of the injuries. However, in his 2008 biography of John, he stated that Wooler ‘suffered bruised ribs and a black eye’.

In his 2005 Beatles biography, Bob Spitz had John beating Wooler ‘viciously, with tightly closed fists. When that didn’t do enough damage, he grabbed a garden shovel that was left in the yard and whacked Bob once or twice with the handle. According to one observer, “Bob was holding his hands to his face and John was kicking all the skin off his fingers.”’ According to Spitz, Wooler was taken away in an ambulance with even more injuries: ‘a broken nose, a cracked collar bone and three broken ribs’.

Do I hear any advance on a broken nose, a cracked collarbone and three broken ribs? Inevitably, the most excessive bid was submitted by Albert Goldman, the most merciless and hyperbolic of all John’s biographers:2 ‘John doubled up his fist and smashed the little disc jockey in the nose. Then, seizing a shovel that was lying in the yard, Lennon began to beat Wooler to death. Blow after blow came smashing down on the defenseless man lying on the ground. It would have ended in murder if John had not suddenly realized: “If I hit him one more time, I’ll kill him!” Making an enormous effort of will, Lennon restrained himself. At that instant three men seized him and disarmed him. An ambulance was called for Wooler, who had suffered a broken nose, a cracked collar-bone, and three broken ribs. Lennon had broken a finger.’

All in all, no other event in the lives of the Beatles illustrates more clearly the random, subjective nature of history, a form predicated on objectivity but reliant on the shifting sands of memory.

So a table of the final tally looks like this:

No one seems to doubt, though, that the following day Wooler contacted Rex Makin, who decided to act for both parties, eventually negotiating a £200 payment to Wooler and an apology. Word soon reached the press about the incident. In charge of damage limitation, Tony Barrow got in touch with John, who was bullishly unrepentant. ‘He told me gruffly, “Wooler was well out of fucking order. He called me a bloody queer so I battered him … I wasn’t that pissed. The bastard had it coming. He teased me, I punched him. Of course I won’t apologise.”’ Barrow then dutifully ‘trimmed and toned and spun’ this unpromising material, so that the next day’s Sunday Mirror reported:

Guitarist John Lennon, 22-year-old leader of the Beatles pop group, said last night, ‘Why did I have to go and punch my best friend? … Bob is the last person in the world I would want to have a fight with. I can only hope he realises that I was too far gone to know what I was doing.’

Recuperating in hospital, Wooler received a conciliatory telegram from John: ‘REALLY SORRY, BOB. TERRIBLY SORRY TO REALIZE WHAT I HAD DONE. WHAT MORE CAN I SAY?’ As it happened, each word had been dictated by Brian Epstein.3

What exactly happened in Spain? Most people agree that when Julian was three weeks old, Brian took the unusual step of taking John on a Spanish holiday à deux. In her first autobiography (1978), Cynthia says that when John asked her if she would mind, ‘I concealed my hurt and envy and gave him my blessing.’ In her second (2005), her memories have altered; now, when John asks her if she would mind, there is no mention of hurt or envy. ‘I said, truthfully, that I wouldn’t.’

The implacable Albert Goldman, on the other hand, states that John only got round to seeing his newborn son a week after his birth, and then, ‘turning to Cynthia, informed her bluntly that he was going off on a short holiday with Brian Epstein’. In the Goldman version, far from acquiescing, ‘Cynthia was outraged by his astonishing news.’ Goldman adds that John was indifferent to Cynthia’s feelings, saying: ‘Being selfish again, aren’t you?’ He appears to have lifted this version of events from Peter Brown’s waspish memoir The Love You Make (1983), though it seems unlikely that Brown himself was privy to John and Cynthia’s discussion.

So, did they or didn’t they? The simple truth is that no one knows, but everyone thinks they know, or at least they want everyone else to think they know. Cynthia covers the matter in two sentences. Pooh-poohing the gossip, she says that after John came back from Spain, ‘He had to put up with sly digs, winks and innuendo that he was secretly gay. It infuriated him: all he’d wanted was a break with a friend, but it was turned into so much more.’

Of the Beatles’ employees, Alistair Taylor and Tony Barrow agree with Cynthia that nothing sexual occurred. Taylor claims that ‘in one of our frankest heart-to-hearts John denied it’. ‘He never wanted me like that,’ he told Taylor, adding, ‘Even completely out of my head, I couldn’t shag a bloke. And I certainly couldn’t lie there and let one shag me. Even a nice guy like Brian. To be honest, the thought of it turns me over.’ Barrow says, ‘John made it abundantly clear to me that there was no two-way traffic along this route … I don’t believe that the relationship between Brian and John became a physical one in Spain or elsewhere. I believe John’s version, which was that he teased Brian to the limit but stopped short when they came to the brink.’

On the other hand, Tony Bramwell claims John told him that he finally allowed Brian to have sex with him just ‘to get it out of the way’. But Bramwell adds that John may have been lying. ‘Those who knew John well, who had known him for years, don’t believe it for a moment.’ However, Peter Brown begs to differ, painting an unfeasibly vivid picture, as though lifted from an airport novel: ‘Drunk and sleepy from the sweet Spanish wine, Brian and John got undressed in silence. “It’s OK, Eppy,” John said, and lay down on his bed. Brian would have liked to have hugged him, but he was afraid. Instead, John lay there, tentative and still, and Brian fulfilled the fantasies he was so sure would bring him contentment, only to awake the next morning as hollow as before.’4

Pete Shotton was closer to John than the others, and less given to speculation. He writes that when John and Brian went away ‘tongues began wagging all over town’. On John’s return, Shotton teased him – ‘So you had a good time with Brian, then?’ – only for John to respond quietly, ‘Actually Pete, something did happen with him one night … Eppy just kept on and on at me. Until one night I finally just pulled me trousers down and said to him, “Oh, for Christ’s sake, Brian, just stick it up me fucking arse then.” And he said to me, “Actually, John, I don’t do that kind of thing. That’s not what I like to do.” “Well,” I said, “what is it you want to do then?” And he said, “I’d really just like to touch you, John.” And so I let him toss me off … So what harm did it do, then, Pete, for fuck’s sake? No harm at all. The poor fucking bastard, he can’t help the way he is.’

So much for John’s associates. Small wonder, then, that his biographers are also divided. Epstein’s biographer Ray Coleman insists nothing sexual occurred: ‘Since the death of Epstein and Lennon, many with no access to, or observation of, both men in their lifetime have peddled the assumption that Brian and John had a sexual liaison. This is despite the lack of any evidence, despite firm declarations of John’s heterosexuality from Cynthia and many other women, and despite the statement by McCartney that he “slept in a million hotel rooms, as we all did, with John and there was never any hint that he was gay”. Coleman argues that Epstein ‘would never have risked so profoundly changing his relationship with them, individually or collectively’. He adds that ‘Epstein was not a predator,’ though there is in fact plenty of evidence to suggest that he was.5