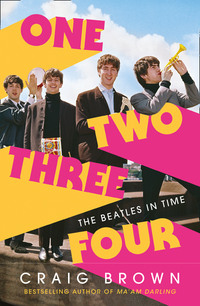

One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

BEATLES CHANGE DRUMMER!

Ringo Starr (former drummer with Rory Storm & the Hurricanes) has joined the Beatles, replacing Pete Best on drums. Ringo has admired the Beatles for years and is delighted with his new arrangement. Naturally he is tremendously excited about the future.

The Beatles comment, ‘Pete left the group by mutual agreement. There were no arguments or difficulties, and this has been an entirely amicable decision.’

On Tuesday September 4th, the Beatles will fly to London to make recordings at EMI Studios. They will be recording numbers that have been specially written for the group.

Mersey Beat front page, 23 August 1962

When the news gets out, Mersey Beat receives a petition for Pete Best’s reinstatement, signed by hundreds of fans. They descend on his family’s home. Mo Best remembers her sitting room ‘bulging with fans, sighing and sobbing’. These fans also picket Mr Epstein’s offices in Whitechapel. The owner of the Cavern, Ray McFall, provides him with a bodyguard. Ringo receives a poison-pen letter.

The Beatles’ next concert at the Cavern is a rocky affair. Pete’s fans heckle them, chanting ‘Pete is Best!’ and ‘Ringo never, Pete Best forever!’ After half an hour of this, George loses his temper and snaps back. In reply, an aggrieved fan punches George, giving him a black eye. A Pete Best fan called Jenny writes a letter of complaint to George, who answers bullishly, ‘Ringo is a much better drummer, and he can smile – which is a bit more than Pete could do. It will seem different for a few weeks, but I think that the majority of our fans will soon be taking Ringo for granted … lots of love from George.’

In time, George is proved right. Fans are fickle. ‘I used to love Pete and was heartbroken when they sacked him,’ one of them, Elsa Breden, tells the Beatles’ biographer Mark Lewisohn over forty years later. ‘But it soon passed and it was as if he’d never been there. They were much better with Ringo, without a doubt. He gave them that solid backbeat – he’s a great rock’n’roll drummer – and he fitted in brilliantly.’

Just six days after Pete’s dismissal, John, Paul, George and Ringo are filmed by Granada TV at a lunchtime concert in the Cavern. Pete goes along to watch them. On the way out, Paul’s father Jim spots him and exclaims triumphantly, ‘Great, isn’t it? They’re on TV!’

‘Sorry, Mr McCartney,’ replies Pete. ‘I’m not the right person to ask.’

Over the next two years, the Beatles collectively gross £17 million.

For his part, Pete Best joins Lee Curtis and the All Stars. When Lee Curtis goes solo, they change their name to the Pete Best All-Stars. Then one of them leaves, and they become the Pete Best Four. Another leaves, and they become the Pete Best Combo. As the fame of the Beatles grows, interest in Pete fades. ‘There was little or no revenue coming in, barely enough to pay my bills, and I reached the stage where I found myself scratching around for enough money to buy a packet of cigarettes. I just couldn’t sit back and ignore the fact that I should have shared in the Beatles’ success, which I considered to be part of my heritage.’

Pete’s wife Kathy works on the biscuit counter at Woolworths. One day in 1967 he waits until she has left for work, goes up to the bedroom, locks the door, blocks any air gaps, places a pillow on the floor in front of the gas fire, and turns on the gas. He is fading away when his brother Rory arrives, smells gas, batters the door down and, screaming ‘Bloody idiot!’ saves his life.

That same year, Hunter Davies is finishing his pioneering biography of the Beatles. He often tells them tales from his travels, and they are always keen to know what old friends are up to. ‘They were mostly interested to hear what had happened, except when the subject of Pete Best came up. They seemed to cut off, as if he had never touched their lives. They showed little reaction when I said he was now slicing bread for £18 a week, though Paul did make a face. John asked a few more questions, but then forgot about it, and they all went back to the song they were recording.’

In 1969 Pete embarks on a career as a civil servant, working in an employment office. For many years his two daughters, Beba and Bonita, have no idea that their dad was once a Beatle.

He is now retired, and, aged seventy-eight, fronts the Pete Best Band. His website, www.petebest.com, promises ‘Right from the first beat, you’ll be immersed in nostalgia, listening to “the best years” of the Beatles, 1960–62.’ The website’s tagline is ‘The Man Who Put the Beat in Beatles’.

In 2019 the Sunday Times estimates Ringo Starr’s wealth at £240 million, which makes him the eighth-richest musician in the world. He is a knight of the realm, maintains homes in London, Los Angeles and Monte Carlo, and is married to Barbara Bach, a former Bond girl. Pete Best’s old drum kit can be seen in Liverpool’s The Beatles Story museum, sad and lonesome, a monument to loss; the tomb of the unknown drummer. On the audio guide, George Martin explains: ‘He was probably the best-looking, but he didn’t say much and he didn’t have the charisma the others had. More importantly, his drumming was OK but it wasn’t top-notch, in my opinion. I didn’t realise that the boys were thinking much the same thing, and so they took that as the final word, a catalyst, and poor Pete got the boot. I’ve always felt a bit guilty about that. But I guess he survived.’

1 North End Music Stores, owned at that stage by Brian Epstein’s father.

20

I arrived at Pete Best’s old house in Hayman’s Green on the evening of day four of the annual Beatles Week. The basement recreated the old Casbah Club. A very basementy basement, dank, dark and sweaty, it was bursting at the seams with men in their seventies who looked like Bernie Sanders or Bernard Manning. Most wore Beatles T-shirts. A tribute band was tuning up in an authentically sixties manner, saying ‘One-two, one-two’ over and over again, with no indication that they would ever make it to three.

The Casbah is less a shrine to the Beatles than to Pete Best. Ringo is the great unmentionable. At the entrance, photographs of the Beatles – John, Paul, George and Pete, all autographed by Pete – were on sale for £15. A newspaper cutting with the headline ‘10,000 SUPPORTING PETE BEST STREET BID’ was pinned to a red baize board. It posed an urgent question. In Liverpool, there’s a Paul McCartney Way and a John Lennon Drive. So why not a Pete Best Avenue?

Out in the garden, a tribute band from Indonesia, the Indonesian Beat Club, composed of five ‘die-hard Beatles lovers’, were playing a spirited version of ‘My Bonnie’, just like Pete and the rest of his band used to do, back in the day. Queuing for a drink, I heard someone mention a Pete Best Fan Club. It is centred around Twitter, where it boasts fifty-three followers. Tweets include ‘PETE is the BEST’, ‘I WANT PETE BEST SO BAAAAAD IT’S DRIVING ME MAD’, ‘Happiness Is Pete Best!’ and the poignant ‘MY PETE BEST GENTLY WEEEEEPSSS’.

Flyers near the entrance advertised The Magical Beatles Museum, run by Pete’s half-brother Roag, the son of Mona Best and Neil Aspinall. Its collection includes Pete’s Premier drum kit. History in the museum stops in June 1962: it is as though Ringo had never lived. Visitors are greeted by signs saying ‘PETE, JOHN, PAUL, GEORGE, STUART’. Roag bills it as ‘not just Liverpool’s most authentic Beatles museum, but the world’s most authentic Beatles museum. My oldest brother Pete Best was the original Beatles drummer with the Beatles from 1960 to 1962. He performed over 1,000 shows and recorded 27 tracks as a Beatle.’

Pete Best’s own website announces that ‘When not undertaking a variety of celebrity duties, Pete has a busy schedule touring with the Pete Best Band. The Pete Best Band captures the sound of the Beatles in their formative years – the early years for many “was” the Beatles.’

21

A Party:

Reece’s Café

9–13 Parker Street, Liverpool

23 August 1962

In July 1962 Cynthia realises she is pregnant. She suspects John will take it badly, so puts off telling him for several days. Eventually, she plucks up the courage. ‘As the news sank in he went pale and I saw the fear in his eyes. “There’s only one thing for it, Cyn,” he said. “We’ll have to get married.”’

She tells him he doesn’t have to; he insists he wants to. The next day, John tells Brian Epstein, who says he doesn’t have to go through with it. The Beatles have just signed their first recording contract, and Brian is worried the news will put the fans off. When John tells Aunt Mimi, she accuses Cynthia of wanting to trap him, and says she’ll have nothing to do with the wedding.

Recognising that John is serious, Brian takes charge, applying for the emergency licence and booking the register office for the first available date, in a fortnight’s time.

On 23 August, Brian, dapper in his pin-striped suit, picks up Cynthia from her bedsit. She is wearing a purple-and-black-checked two-piece suit over a frilly high-necked white blouse, with black shoes and a black bag. Brian takes her in a chauffeur-driven car to Mount Pleasant register office. On the way, he tells her she is looking lovely, and does his best to calm her nerves.

When they arrive, John, Paul and George are already pacing about in the waiting room, dressed in smart black suits. Cynthia thinks they all look ‘horribly nervous’. Cynthia’s brother Tony and his wife Marjorie are there too.

As the registrar begins to speak, a workman outside starts a pneumatic drill, but they struggle on. The ceremony takes a matter of minutes. They sign the register: John Winston Lennon, 21, Musician (Guitar) and Cynthia Powell, 22, Art Student (School). Now what? Brian suggests they all go to Reece’s, round the corner, for lunch. They opt for the cheaper café on the ground floor rather than the more expensive Famous Grill Room on the top floor.

The bride and groom and their five guests queue for soup, chicken and trifle. Alcohol is not available, so they all toast the happy couple with water. John has a look of pride. Cynthia is over the moon: ‘A full church wedding with all the extras couldn’t have made me happier.’

Brian presents them with a silver-plated ashtray, engraved with the message ‘Good luck JOHN & CYNTHIA. Brian, Paul & George 23 Aug 62’, as well as a shaving kit in a leather pouch embossed ‘JWL’, which John will take everywhere. The lunch – fifteen shillings a head – is on Brian, who also announces that he has a bolt-hole in Falkner Street where John and Cynthia can live for as long as they want. Cynthia is so excited that she gives him a hug. Brian looks embarrassed.

That night the Beatles have a gig in Chester, so Cynthia takes the opportunity to make the flat nice. At the gig, John appears out of sorts, losing his temper with the support act and yelling, ‘You’re doing all our fucking numbers!’ He doesn’t tell anyone that he’s just got married. Even the Beatles’ new drummer, Ringo, is kept in the dark.

22

In November 1962 a twenty-two-year-old Sheffield entrepreneur with the unusual name of Peter Stringfellow was casting around for an act for his new nightclub, the Black Cat. Though the Black Cat sounded with-it, it was just the name he gave St Aidan’s church hall on the nights he hired it.

Searching through the New Musical Express, Stringfellow spotted an advertisement for a group called the Beatles. They seemed to be just what he wanted: at the beginning of October, their song ‘Love Me Do’ had been his very first record request from a punter; he had been playing it, on and off, ever since.

There was no phone at his parents’ house, so he went to a public call box and was put through to the Beatles’ manager, a Mr Epstein, who told him that the Beatles would cost £50.

‘£50!’ replied Stringfellow. ‘Excuse me, I pay Screaming Lord Sutch £50, and nobody has heard of the Beatles!’

Epstein replied that, unlike Sutch, the Beatles had a record in the charts. Stringfellow knew that ‘Love Me Do’ was actually moving down the charts. He said he would think about it.

The next day he called Epstein back, saying he was prepared to pay £50. Epstein said the price had gone up to £65. Stringfellow felt that Epstein was as nervous as he was himself. He sensed that the Beatles were in real demand, and that their success was becoming more than Epstein could cope with. Once again, Stringfellow said he’d think about it.

True to his word, he called back two days later, and said, yes, he could manage £65. Mr Epstein replied that the price had now risen to £100. ‘The Beatles have another single coming out and this will go to the top of the charts,’ he said confidently. Stringfellow tried to haggle, but Mr Epstein said he wouldn’t take anything less than £90. They finally agreed on £85. Stringfellow was shaken. ‘I came out of the telephone in a sweat because I had never paid that amount of money to a band before.’

There was an eerie gap between ‘Love Me Do’ leaving the charts and the release of ‘Please Please Me’. The Beatles seemed to go quiet. Stringfellow began to panic. Had he just wasted all his money?

He placed an advertisement in the NME announcing that the Beatles would be playing at the Black Cat in April, and ordered tickets from the printer, each priced at four shillings. Applications came pouring in, even from Scotland, so he went back to the printers and asked them to put up the price to five shillings. By January he had sold over 1,500 tickets, way beyond the capacity of the Black Cat.

He looked around for a larger venue, hit upon the Azena Ballroom, Sheffield’s flashiest dance hall, and placed an advertisement in the NME announcing the change of venue. By 2 April he had sold two thousand tickets; on the night itself, a further thousand people turned up on the off-chance of getting in.

23

I arrived too late at the International Beatles Week in Liverpool to catch the opening act, Les Sauterelles. They formed in 1962, and according to the brochure, ‘soon became the most popular Swiss Beat Band of the sixties. In the hot summer of ’68, their single “Heavenly Club” was number one for six weeks in the Swiss Charts.’

Next up were a Beatles tribute band from Hungary called the Bits, followed by the Norwegian Beatles, ‘probably the world’s northernmost Beatles tribute band’, and then Clube Big Beatles from Brazil, who are apparently soon to open their own Cavern Club in São Paulo. Performers on the indoor stage included the Bertils from Sweden, the Fab Fourever (‘Canada’s Premiere Tribute to the Beatles’), Bestbeat from Serbia, crowned ‘one of the thirty most prominent Beatles tribute bands on the planet’ by Newsweek in 2012, and B.B. Cats, an all-female tribute band from Tokyo who specialise in playing the Beatles’ Hamburg repertoire.

There are over a thousand Beatles tribute acts in the world today. Many of them – the Tefeatles from Guatemala, Rubber Soul from Brazil, the Nowhere Boys from Colombia, Abbey Road from Spain – have now been together longer than the Beatles themselves: Britain’s Bootleg Beatles and Australia’s Beatnix have both been going for forty years.

In the evening, I joined the long and winding queue outside the Grand Central Hall to see the Fab Four from California, one of the most successful Beatles tribute bands in the world. Most of those queuing were around the age of seventy, which would have made them fifteen or so at the height of Beatlemania. The men wore baggy jeans and Beatles T-shirts; the women slacks and generous tops. One or two people were in wheelchairs. At most rock concerts, fans rush to get close to the stage, but when the doors to the Grand Central Hall opened, most people rushed upstairs, to where the seats were.

A depressing man in jeans and a knitted bonnet opened the show, moaning his way through John’s passive-aggressive ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, accompanying himself with jerky pyrotechnics on an acoustic guitar. What was I doing there, with these senior citizens togged up in their Beatles gear? With a change of clothes it might almost have been a reunion of Second World War veterans, gathered for a fly-past of Spitfires.

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

In the 1970s, my parents used to watch a TV programme called The Good Old Days. The audience would dress up as Edwardians, the men in straw boaters, fancy blazers and walrus moustaches, the women in feather-rimmed hats and voluminous dresses with high-boned collars. They would gasp adoringly as the high-camp Master of Ceremonies, Leonard Sachs, introduced each music-hall act – tap dancer, conjuror, barbershop quartet – with a stream of elaborate words: ‘Prestidigitational!’ (‘Oooh!’), ‘Plenitudinous!’ (‘Ahh!’), ‘Sesquipidalianism!’ (‘Oooh!’), and then banged his gavel. At the curtain-call everyone would join in with a sing-song of ‘Down at the Old Bull and Bush’. It was what was then known as a trip down memory lane, viewers at home happy to collude in the deception that time could be reversed, and the dead revived.

Was this Beatles revival another quest for the same old thing – dreams of blue remembered hills?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

Such were my maudlin reflections as the Fab Four took to the stage. But then they started to play ‘She Loves You’, and they sounded just like the Beatles and, to my fading eyes, looked just like them too – Paul arching his eyebrows and rolling his eyes to the ceiling, George slightly dreamy and distant, Ringo rocking his head from side to side, John with his legs wide apart, as though astride a donkey. I was witnessing something closer to a wonderful conjuring trick. One half of your brain recognises that these are not the Beatles: how could they be? But the other half is happy to believe that they are. It is like watching a play: yes, of course you know that the couple onstage are actors, but on some other level you think they are Othello and Desdemona. The drama lies in the interplay of knowledge and imagination. And with the Fab Four, there is another illusion at work, equally convincing, equally transient: for as long as they play, we are all fifty years younger, gazing in wonder at the Beatles in their prime.

24

Helen Shapiro had been asked to leave her school choir because she could never resist jazzing up the harmonies.

So, aged twelve, she formed a group, Suzie and the Hula-Hoops, with her schoolmates Mark Feld,1 Stephen Gould and Susan Singer, but they disbanded soon afterwards. Helen liked to hang around the stage door of the Hackney Empire, up the road from her family home, spotting stars like Adam Faith, Billy Fury, Cliff Richard and Lord Rockingham’s Eleven. Once, she even managed to get Marty Wilde’s autograph.

Aged thirteen, she was determined to become either an air hostess or a singer. This choice was decided for her when her Uncle Harry happened to spot an advertisement for the Maurice Burman School of Modern Pop Singing, where Alma Cogan had once been a pupil.Burman himself had drummed with leading dance bands before the war, and now wrote a regular column for Melody Maker. Upon meeting little Helen, he was so excited by her deep, bluesy voice that he waived the fee. Every Saturday Helen attended his school, on the corner of Baker Street and Marylebone Road, and there she learned scales, diction, phrasing and microphone technique.

After six months Burman got in touch with his old friend, the conductor and producer Norrie Paramor. Paramor suggested Helen record a test tape at the EMI studios at Abbey Road. She sang ‘Birth of the Blues’. Paramor found it hard to believe that these powerful, poised vocals sprang from a thirteen-year-old.

EMI gave Helen a contract. Instead of a percentage, they offered her a penny per single, and sixpence for each twelve-track LP. If she was a success, the amount would rise to three farthings per track, up to a maximum of tuppence a single. ‘It all went totally over my head. The people from EMI were all clever businessmen while I was just a young girl who wanted to sing. I never was interested in the financial side of things, until it was too late.’

Helen and her parents thought she should change her name: at that time Jewish performers tended to change their names to avoid anti-Semitism. But Norrie Paramor felt that most people wouldn’t twig that Shapiro was a Jewish surname, and it sounded dashing, so they decided to stick with it.

Helen’s first single, ‘Don’t Treat Me Like a Child’, was released on 10 February 1961. It seemed to have peaked at a satisfactory number 28 in the charts, but then she appeared on the first edition of the new pop music show Thank Your Lucky Stars, and it zoomed to number 4. Helen began to be recognised in the streets.

Her next two songs, ‘You Don’t Know’ and ‘Walkin’ Back to Happiness’, both sold over a million copies, and reached number 1 in the charts. Helen was voted Best Female Act in 1961, and again the following year.

Towards the end of 1962, the promoter Arthur Howes told her about the line-up for her next British tour. ‘We’re going to put a nice package together for you. We’ve got Kenny Lynch, Danny Williams. Red Price will be backing you again. Dave Allen is compering, there’s a girls’ singing group, the Honeys, and a vocal group, the Kestrels. Then we’ve got this new group, the Beatles. I don’t know whether you’ve heard their record, “Love Me Do”?’

Helen certainly did know about the Beatles: ‘They were the funny fellows with the funny hair.’

Her tour kicked off at the Gaumont in Bradford on 2 February. The Red Price Band opened the show, then came the Honeys, the comedian (and compere) Dave Allen, and the Beatles, with Danny Williams (‘Britain’s Johnny Mathis’) closing the first half. After the interval the Red Price Band appeared again, followed by the Kestrels, Kenny Lynch, Dave Allen again, and finally, topping the bill, Helen Shapiro.

During the sound checks in Bradford, Helen was introduced to the Beatles’ bass player, Paul. ‘I made some comment about liking “Love Me Do” and he introduced me to the rest of the guys who were really happy because this was their first major concert tour. They’d performed in clubs and ballrooms in Hamburg and Liverpool but never done anything like the pop package and were eager to be onstage.’

At this point, one of them mentioned that they had written a song called ‘Misery’ for Helen, but it had been turned down on her behalf by Norrie Paramor. Helen apologised, saying she hadn’t known about it.

When the Beatles took to the stage, Helen was struck by quite how loud they were. They were used to a noisier crowd. ‘They soon cottoned on to the fact that they didn’t need to turn the sound up quite so much when people were sitting listening rather than dancing … They had a lot to learn.’

Her management encouraged Helen to travel by herself in a special limousine, to reflect her star status, but she preferred sitting in the coach with the supporting acts. ‘I wouldn’t have missed it for the world, especially while the Beatles were with us.’ Together on the coach, the Beatles would bring out their guitars, and Helen would sing a song like ‘The Locomotion’. She remembered how Paul would practise writing his autograph over and over again, and then ask her what she thought of it. On one of these coach rides John and Paul hit upon the idea of running up to the microphone together and singing ‘Whoooo!’, a routine that within a matter of weeks would be setting off explosions of ecstasy among their fans.

One night Helen let the Beatles into her changing room so they could watch themselves on television for the first time. John was surprised by the way he looked, particularly the odd, jockey-like stance he adopted onstage. They kept nudging one another and commenting. ‘Eh, look at that.’ ‘You look awful.’