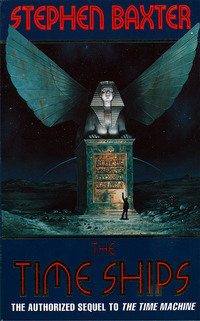

The Time Ships

I puzzled over this for a few moments, my desire to explore further battling with my apprehension. Then an idea struck me. I opened my knapsack and took out my candles and camphor blocks. With rough haste I shoved these articles into crevices in the Time Machine’s complex construction. Then I went around the machine with lighted matches until every one of the blocks and candles was ablaze.

I stood back from my glowing handiwork with some pride. Candle flames glinted from the polished nickel and brass, so that the Time Machine was lit up like some Christmas ornament. In this darkened landscape, and with the machine poised on this denuded hill-side, I would be able to see my beacon from a fair distance. With any luck, the flames would deter any Morlocks – or if they did not, I should see the diminution of the flames immediately and could come running back, to join battle.

I fingered the poker’s heavy handle. I think a part of me hoped for just such an outcome; my hands and lower arms tingled as I remembered the queer, soft sensation of my fists driving into Morlock faces!

At any rate, now I was prepared for my expedition. I picked up my Kodak, lit a small oil lamp, and made my way across the hill, pausing after every few paces to be sure the Time Machine rested undisturbed.

5

THE WELL

I raised my lamp, but its glow carried only a few feet. All was silent – there was not a breath of wind, not a trickle of water; and I wondered if the Thames still flowed.

For lack of a definite destination, I decided to make towards the site of the great food hall which I remembered from Weena’s day. This lay a little distance to the north-west, further along the hill-side past the White Sphinx, and so this was the path I followed once more – reflecting in Space, if not in Time, my first walk in Weena’s world.

When last I made this little journey, I remembered, there had been grass under my feet – untended and uncropped, but growing neat and short and free of weeds. Now, soft, gritty sand pulled at my boots as I tramped across the hill.

My vision was becoming quite adapted to this night of patchy star-light, but, though there were buildings hereabout, silhouetted against the sky, I saw no sign of my hall. I remembered it quite distinctly: it had been a grey edifice, dilapidated and vast, of fretted stone, with a carved, ornate doorway; and as I had walked through its carved arch, the little Eloi, delicate and pretty, had fluttered about me with their pale limbs and soft robes.

Before long I had walked so far that I knew I must have passed the site of the hall. Evidently – unlike the Sphinx and the Morlocks – the food palace had not survived in this History – or perhaps had never been built, I thought with a shiver; perhaps I had walked – slept, even taken a meal! – in a building without existence.

The path took me to a well, a feature which I remembered from my first jaunt. Just as I recalled, the structure was rimmed with bronze and protected from the weather by a small, oddly delicate cupola. There was some vegetation – jet-black in the star-light – clustered around the cupola. I studied all this with some dread, for these great shafts had been the means by which the Morlocks ascended from their hellish caverns to the sunny world of the Eloi.

The mouth of the well was silent. That struck me as odd, for I remembered hearing from those other wells the thud-thud-thud of the Morlocks’ great engines, deep in their subterranean caverns.

I sat down by the side of the well. The vegetation I had observed appeared to be a kind of lichen; it was soft and dry to the touch, though I did not probe it further, nor attempt to determine its structure. I lifted up the lamp, meaning to hold it over the rim and to see if there might be returned the reflection of water; but the flame flickered, as if in some strong draught, and, in a brief panic at the thought of darkness, I snatched the lamp back.

I ducked my head under the cupola and leaned over the well’s rim, and was greeted by a blast of warm, moist air into the face – it was like opening the door to a Turkish bath – quite unexpected in that hot but arid night of the future. I had an impression of great depth, and at the remote base of the well I fancied my dark-adapted eyes made out a red glow. Despite its appearance, this really was quite unlike the wells of the first Morlocks. There was no sign of the protruding metal hooks in the side, intended to support climbers, and I still detected no evidence of the machinery noises I had heard before; and I had the odd, unverifiable impression that this well was far deeper than those Morlocks’ cavern-drilling.

On a whim, I raised my Kodak and dug out the flash lamp. I filled up the trough of the lamp with blitzlichtpulver, lifted the camera and flooded the well with magnesium light. Its reflections dazzled me, and it was a glow so brilliant that it might not have been seen on earth since the covering of the sun, a hundred thousand years or more earlier. That should have scared away the Morlocks if nothing else! – and I began to concoct protective schemes whereby I could connect the flash to the unattended Time Machine, so that the powder would go off if ever the machine was touched.

I stood up and spent some minutes loading the flash lamp and snapping at random across the hillside around the well. Soon a dense cloud of acrid white smoke from the powder was gathering about me. Perhaps I would be lucky, I reflected, and would capture for the wonderment of Humanity the rump of a fleeing, terrified Morlock!

… There was a scratching, soft and insistent, from a little way around the well rim, not three feet from where I stood.

With a cry, I fumbled at my belt for my poker. Had the Morlocks fallen on me, while I daydreamed?

Poker in hand, I stepped forward with care. The rasping noises were coming from the bed of lichen, I realized; there was some form, moving steady through those tiny, dark plants. There was no Morlock here, so I lowered my club, and bent over the lichen bed. I saw a small, crab-like creature, no wider than my hand; the scratching I heard was the rasp of its single, outsize claw against the lichen. The crab’s case seemed to me to be jet black, and the creature was quite without eyes, like some blind creature of the ocean depths.

So, I reflected as I watched this little drama, the struggle to survive went on, even in this benighted darkness. It struck me that I had seen no signs of life – save for the glimpses of Morlock – away from this well, in all my visit here. I am no biologist, but it seemed clear that the presence of this fount of warm, moist air would be bound to attract life, here on a world turned to desert, just as it had attracted this blind farmer-crab and his crop of lichen. I speculated that the warmth must come from the compressed interior of the earth, whose volcanic heat, evident in our own day, would not have cooled significantly in the intervening six hundred thousand years. And perhaps the moisture came from aquifers, still extant below the ground.

It may be, I mused, the surface of the planet was studded with such wells and cupolas. But their purpose was not to admit access to the interior world of the Morlocks – as in that other History – but to release the earth’s intrinsic resources to warm and moisten this planet deprived of its sun; and such life as had survived the monstrous engineering I had witnessed now clustered around these founts of warmth and moisture.

My confidence was increasing – making sense of things is a powerful tonic for my courage, and after that false alarm with the crab, I had no sense of threat – and I sat again on the lip of the well. I had my pipe and some of my tobacco in my pocket, and I packed the bowl full and lit up. I began to speculate on how this History might have diverged from the first I had witnessed. Evidently there had been some parallels – there had been Morlocks and Eloi here – but their grisly duality had been resolved, in ages past.

I wondered why should such a show-down between the races occur – for the Morlocks, in their foul way, were as dependent on the Eloi as were Eloi on Morlock, and the whole arrangement had a sort of stability.

I saw a way it might have come about. The Morlocks were of debased human stock, after all, and it is not in man’s heart to be logical about things. The Morlock must have known that he depended on the Eloi for his very existence; he must have pitied and scorned him – his remote cousin, yet reduced to the status of cattle. And yet –

And yet, what a glorious morning made up the brief life of the Eloi! The little people laughed and sang and loved across the surface of the world made into a garden, while your Morlock must toil in the stinking depths of the earth to provide the Eloi with the fabric of their luxurious lives. Granted the Morlock was conditioned for his place in creation, and would no doubt turn in disgust from the Eloi’s sunlight and clear water and fruit, even were it offered to him – but still, might he not, in his dim and cunning fashion, have envied the Eloi their leisure?

Perhaps the flesh of the Eloi turned sour in the Morlock’s rank mouth, even as he bit into it in his dingy cave.

I envisaged, then, the Morlocks – or a faction of them – arising one night from their tunnels under the earth, and falling on the Eloi with their weapons and whip-muscled arms. There would be a great Culling – and this time, not a disciplined harvesting of flesh, but a full-blooded assault with one, unthinking purpose: the final extinction of the Eloi.

How must the lawns and food palaces have run with blood, those ancient stones echoing to the childish bleating of the Eloi!

In such a contest there could be only one victor, of course. The fragile people of futurity, with their hectic, consumptive beauty, could never defend themselves against the assaults of organized, murderous Morlocks.

I saw it all – or so I thought! The Morlocks, triumphant at last, had inherited the earth. With no more use for the garden-country of the Eloi, they had allowed it to fall into ruin; they had erupted from the earth and – somehow – brought their own Stygian darkness with them to cover the sun! I remembered how Weena’s folk had feared the nights of the new moon – she had called them ‘The Dark Nights’ – now, it seemed to me, the Morlocks had brought about a final Dark Night to cover the earth, forever. The Morlocks had at last murdered the last of earth’s true children, and even murdered earth herself.

Such was my first hypothesis, then: wild and gaudy – and wrong, in every particular!

… And I became aware, with almost a physical shock, that in the middle of all this historical speculation I had quite forgotten my regular inspections of the abandoned Time Machine.

I got to my feet and glared across the hill-side. I soon picked out the machine’s candle-lit glow – but the lights I had built flickered and wavered, as if opaque shapes were moving around the machine.

They could only be Morlocks!

6

MY ENCOUNTER WITH THE MORLOCKS

With a spurt of fear – and, I have to acknowledge it, a lust for blood which pulsed in my head – I roared, lifted my poker-club, and pounded back along the path. Careless, I dropped my Kodak; behind me I heard a soft tinkle of breaking glass. For all I know, that camera lies there still – if I may use the phrase – abandoned in the darkness.

As I neared the machine, I saw they were Morlocks all right – perhaps a dozen of them, capering around the machine. They seemed alternately attracted and repelled by my lights, exactly like moths around candles. They were the same ape-like creatures I remembered – perhaps a little smaller – with that long, flaxen hair across their heads and backs, their skin a pasty white, arms long as monkeys’, and with those haunting red-grey eyes. They whooped and jabbered to each other in their queer language. They hadn’t yet touched the Time Machine, I noted with some relief, but I knew it was a matter of moments before those uncanny fingers – ape-like, yet clever as any man’s – reached out for the sparkling brass and nickel.

But there would be no time for that, for I fell upon these Morlocks like an avenging angel.

I laid about me with my poker and my fist. The Morlocks jabbered and squealed, and tried to flee. I grabbed one of the creatures as it ran past me, and I felt again the worm-pallor cold of Morlock flesh. Hair like spider-web brushed across the back of my hand, and the animal nipped at my fingers with its small teeth, but I did not yield. I wielded my club, and I felt the soft, moist collapse of flesh and bone.

Those grey-red eyes widened, and closed.

I seemed to watch all this from a small, detached part of my brain. I had quite forgotten all my intentions to return proof of the working of time travel, or even to find Weena: I suspected at that moment that this was why I had returned into time – for this moment of revenge: for Weena, and for the murder of the earth, and my own earlier indignity. I dropped the Morlock – unconscious or dead, it was no more than a bundle of hair and bones – and grabbed for its companions, swinging my poker.

Then I heard a voice – distinctively Morlock, but quite unlike the others in tone and depth – it issued a single, imperative syllable. I turned, my arms soaked in blood up to the elbows of my jacket, and made ready for more fighting.

Before me, now, stood a Morlock who did not run from me. Though he was naked like the rest, his coat of hair seemed to have been brushed and prepared, so that he had something of the effect of a groomed dog, made to stand upright like a man. I took a massive step forward, my club held firm in both hands.

Calmly, the Morlock raised his right hand – something glinted there – and there was a green flash, and I felt the world tip backwards from under me, pitching me down beside my glowing machine; and I knew no more!

7

THE CAGE OF LIGHT

I came to my senses slowly, as if emerging from a deep and untroubled sleep. I was lying on my back, with my eyes closed. I felt so comfortable that for a moment I imagined I must be in my own bed, in my house in Richmond, and that the pink glow showing through my eyelids must be the morning sun seeping around my curtains …

But then I became aware that the surface beneath me – though yielding and quite warm – did not have the softness of a mattress. I could feel no sheets beneath me, nor blankets above me.

Then, in a flash, it returned to me: all of it – my second flight through time, the darkening of the sun, and my encounter with the Morlocks.

Fear flooded me, stiffening my muscles and tightening my stomach. I had been taken by the Morlocks! I snapped my eyes open –

And I was instantly dazzled by a brilliant illumination. It came from a remote disc of intense white light, directly above me. I cried out and flung an arm across my blinded eyes; I rolled over, pressing my face against the floor.

I pushed myself up to a crawling position. The floor was warm and giving, like leather. At first, my vision was full of dancing images of that blazing disc, but at last I was able to make out my own shadow under me. And then, still on all fours, I noticed the queerest thing yet: that the surface beneath me was clear, as if made of some flexible glass, and – where my shadow shielded out the light – I could see stars, quite clearly visible through the floor beneath me. I had been deposited on some transparent platform, then, with this starry diorama below: it was as if I had been brought to some inverted planetarium.

I felt queasy to the stomach, but I was able to stand up. I had to shield my eyes with my hand against the unremitting glare from above; I wished I had not lost the hat I had brought from 1891! I still wore my light suit, although it now bore stains of sand and blood, particularly around the sleeves – though some efforts had been made to clean me up, I noticed with surprise, and my hands and arms were clear of Morlock blood, mucus and ichor. My poker was gone, and I could see no sign of my knapsack. I had been left my watch, which hung on a chain from my waistcoat, but my pockets were empty of matches or candles. My pipe and tobacco were gone, too, and I felt an incongruous stab of regret for that – in the middle of all that mystery and peril!

A thought struck me, and my hands flew to my vest pocket – and they found the Time Machine’s twin levers still there. I breathed relief.

I looked around. I was standing on a flat, even Floor of the leather-like, clear substance I have described. I was close to the centre of a splash of light perhaps thirty yards wide, cast on that enigmatic Floor by the source above me. The air was quite dusty, so that it was easy to pick out the rays of light as they flooded down over me. You must imagine me standing there in the light, as if at the bottom of some dusty mine shaft, blinking up at the noonday sun. And indeed it looked like sunlight – but I could not understand how the sun could have been uncovered, nor come to be stationary above me. My only hypothesis was that I had been moved, while unconscious, to some point on the Equator.

Fighting a mounting panic, I paced around my circle of light. I was quite alone, and the Floor was bare – save for trays, two of them, bearing containers and cartons, which rested on the Floor perhaps ten feet from where I had been laid. I peered out into the encircling gloom, but could make out nothing, even with my eyes quite shielded. I could see no containing walls to this chamber. I clapped my hands, causing dust motes to dance in the lit-up air. The sound was deadened, and no echo was returned. Either the walls were impossibly remote, or they were lagged with some absorbent substance; either way, I had no clue as to their distance.

There was no sign of the Time Machine.

I felt a deep, peculiar fear, there on that plain of soft glass; I felt naked and exposed, with nowhere to shelter my back, no corner to make into a fastness.

I approached the trays. I peered at the cartons, and lifted their lids: there was one large, empty pail, and a bowl of what looked like clear water, and in the last dish there were fist-sized bricks of what I guessed to be food – but it was food processed into smooth yellow, green or red slabs, so that its origins were quite unrecognizable. I poked at the food with a reluctant fingertip: they were cold and smooth, rather like cheese. I had not eaten since Mrs Watchets’s breakfast, many hours of my tangled life ago, and I was aware of a mounting pressure in my bladder: a pressure which, I guessed, the empty pail was intended to help relieve. I could see no reason why the Morlocks, having preserved me this long, should choose to poison me, but nevertheless I was reluctant to accept their hospitality – and even more so to lose my dignity by using the pail!

So I stalked around the tray, and around that circle of light, sniffing like some animal suspicious of a trap. I even picked up the cartons and trays, to see if I could make some weapon of them – perhaps I could hammer out some kind of blade – but the trays were manufactured of a silvery metal, a little like aluminium, so thin and soft it crumpled in my hands. I could no more stab a Morlock with this than with a sheet of paper.

It struck me that these Morlocks had behaved with remarkable gentleness. It would have been the work of a moment to have finished me off while I lay unconscious, but they had stayed their brutish hands – even, with surprising skill, it seemed, made efforts to clean me up.

I was immediately suspicious, of course. For what purpose had they preserved my life? Did they intend to keep me alive, in order to dig out of me – by whatever foul means – the secret of the Time Machine?

I turned away from the food deliberately, and I stepped out of the ring of light, and into the darkness beyond. My heart was hammering; there was nothing tangible to stop me leaving that illuminated shaft, but my apprehension, and my craving for light, held me in there almost as effectively.

At last, I chose a direction at random, and walked into the darkness, my arms held loose at my side, my fists curled and ready. I counted out the paces – eight, nine, ten … Beneath my feet, more clearly visible now that I was away from the light, I could see the stars, an inverted hemisphere of them; I felt again as if I were standing on the roof of some planetarium. I turned and looked back; there was the dusty light pillar, reaching up to infinity, with the scattering of dishes and food at its base on the bare Floor.

It was all quite incomprehensible to me!

As the unchanging Floor wore away beneath me, I soon gave up counting my steps. The only light was the glow of that central needle-shaft of light and the faint gleam of the stars beneath me, by which I could just make out the profile of my own legs; the only sounds were the scratch of my own breathing, and the soft impacts of my boots on the glassy surface.

After perhaps a hundred yards, I turned through a corner and began to pace out a path around my light-needle. Still I found nothing but darkness, and the stars beneath my feet. I wondered if in all this blackness I should encounter those strange, floating Watchers who had accompanied me on my second voyage through time.

Despair began to sink deep into my soul as I blundered on, and I soon began to wish that I could be transported from this place to Weena’s garden-world, or even that night landscape where I had been captured – anywhere with rocks, and plants, and animals, and a recognizable sky, for me to work with! What kind of place was this? Was I in some chamber, buried deep in the hollowed-out earth? What terrible tortures were the Morlocks devising for me? Was I doomed to spend the rest of my life in this alien barrenness?

For a period I was quite unhinged, by my isolation and my awful sense of being stranded. I did not know where I was, nor where the Time Machine was, and I did not expect to see my home again. I was a strange beast, stranded in an alien world. I called out to the dark, alternately issuing threats and entreaties for mercy or release; and I slammed my fists against the bland, unyielding Floor, without result. I sobbed, and ran, and cursed myself for my unmatched folly – having once escaped the clutches of the Morlocks – to have immediately returned myself to the same trap!

In the end I must have bawled like a frustrated child, and I used up my strength, and I sank in the darkness to the ground, quite exhausted.

I think I dozed a while. When I came to myself, nothing in my condition had changed. I got myself to my feet. My anger and frenzy had burned themselves out and, though I felt as desolate as ever in my life, I made room for my body’s simple human needs: hunger and thirst being primary among them.

I returned, tired out, to my light shaft. That pressure in my bladder had continued to build. With a feeling of resignation, I picked up the pail that had been provided for me, carried it off into the dark a little way – for modesty’s sake, as I knew Morlocks must be watching – and when I had done I left it there, out of sight.

I surveyed the Morlock food. It was a bleak prospect: it looked no more appetizing than earlier, but I was just as hungry. I picked up the bowl of water – it was the size of a soup bowl – and raised it to my lips. It was not a pleasant drink – tepid and tasteless, as if all the minerals had been distilled out of it – but it was clear and it refreshed my mouth. I held the liquid on my tongue for a few seconds, hesitating at this final hurdle; then, deliberately, I swallowed.

After a few minutes I had suffered no ill effects I could measure, and I took a little more of the water. I also dabbed a corner of my handkerchief on the bowl, and wiped the water across my brow and hands.