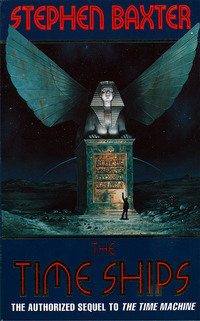

The Time Ships

I turned to the food itself. I picked up one greenish slab of it. I snapped off a corner: it broke easily, was green all the way through, and crumbled a little like a Cheddar. My teeth slid into the stuff. As to its flavour: if you have ever eaten a green vegetable, say broccoli or sprouts, boiled to within an inch of disintegration, then you have something of its savour; members of the less well-appointed London clubs will recognize the symptoms! But I bit into my slab until it was half gone. Then I picked up the other slabs to try them; although their colours varied, their texture and flavour differed not a whit.

It did not take many mouthfuls of that stuff to sate me, and I dropped the fragments on their tray and pushed it away.

I sat on the Floor and peered into the dark. I felt an intense gratitude that the Morlocks had at least provided me with this illumination, for I imagined that had I been deposited on this empty, featureless surface in a darkness broken only by the star images beneath me, I might have gone quite mad. And yet I knew, at the same time, that the Morlocks had provided this ring of light for their own purposes, as an effective means to keep me in this place. I was all but helpless, a prisoner of a mere light ray!

A great weariness descended on me. I felt reluctant to lose consciousness once more – to leave myself defenceless – but I could see little prospect of staying awake forever. I stepped out of the ring of light and a little way away into the darkness, so that I felt, at least, some security from its cover of night. I took off my jacket and folded it up into a pillow for my head. The air was quite warm, and the soft Floor also seemed heated, so I should not go cold.

So, with my portly body stretched out over the stars, I slept.

8

A VISITOR

I awoke after an interval I could not measure. I lifted my head and glanced around. I was alone in the dark, and all seemed unchanged. I patted my vest pocket; the Time Machine levers were still safely there.

As I tried to move, stiffness sent pain shooting along my legs and back. I sat up, awkward, and got to my feet feeling every year of my age; I was inordinately grateful that I had not had to leap into action to fend off a tribe of marauding Morlocks! I performed a few rusty physical jerks to loosen up my muscles; then I picked up my jacket, smoothing out its creases, and donned it.

I stepped forward into the light ring.

The trays, with food cartons and toilet pail, had been changed, I found. So they were watching me! – well, it was no more than I had suspected. I took the lids off the cartons, only to find the same depressing slabs of anonymous fodder. I made a breakfast of water and some of the greenish stuff. My fear was gone, to be replaced by a numbing sense of tedium: it is remarkable how rapidly the human mind can accommodate the most remarkable of changed circumstances. Was this to be my fate from now on? – boredom, a hard bed, lukewarm water, and a diet of slabs of boiled cabbage? It was like being back at school, I reflected with gloom.

‘Pau.’

The single syllable, softly spoken, sounded as loud to me in all that silence as a gun shot.

I cried out, scrambled to my feet, and held out my food slabs – it was absurd, but I lacked any other weapon. The sound had come from behind me, and I whirled around, my boots squealing on the Floor.

A Morlock stood there, just beyond the edge of my light circle, half-illuminated. He stood upright – he did not share the crouching, ape-like gait of those creatures I had encountered before – and he wore goggles that made a shield of blue glass which coated his huge eyes, turning them black to my view. ‘Tik. Pau,’ this apparition pronounced, his voice a queer gurgle.

I stumbled backwards, stepping on a tray with a clatter. I held up my fists. ‘Don’t come near me!’

The Morlock took a single pace forward, coming closer to the light shaft; despite his goggles, he flinched a little from the brightness. This was one of that new breed of advanced-looking Morlock, one of which had stunned me, I realized; he seemed naked, but the pale hair which coated his back and head was cut and shaped – deliberately – into a rather severe style, square about the breast bone and shoulders, giving it something of the effect of a uniform. He had a small, chinless face, something like an ugly child’s.

A ghost of memory of that sweet sensation of Morlock skull cracking under my club returned to me. I considered rushing this fellow, knocking him to the ground. But what would it avail me? There were uncounted others, no doubt, out there in the dark. I had no weapons, not even my poker, and I recalled how this chap’s cousin had raised that queer gun against me, knocking me down without effort.

I decided to bide my time.

And besides – this might seem strange! – I found my anger was dissipating, into an unaccountable feeling of humour. This Morlock, despite the standard wormy pallor of his skin, did look comical: imagine an orang-utan, his hair clipped short and dyed pale yellow-white, and then encouraged to stand upright and wear a pair of gaudy spectacles, and you’ll have something of the effect of him.

‘Tik. Pau,’ he repeated.

I took a step towards him. ‘What are you saying to me, you brute?’

He flinched – I imagined he was reacting to my tone rather than my words – and then he pointed, in turn, to the food slabs in my hands. ‘Tik,’ he said. ‘Pau.’

I understood. ‘Good heavens,’ I said, ‘you are trying to talk to me, aren’t you?’ I held up my food slabs in turn. ‘Tik. Pau. One. Two. Do you speak English? One. Two …’

The Morlock cocked his head to one side – the way a dog will sometimes – and then he said, not much less clearly than I had, ‘One. Two.’

‘That’s it! And there’s more where that came from – one, two, three, four … ’

The Morlock strode into my light circle, though I noticed he kept out of my arm’s reach. He pointed to my water bowl. ‘Agua.’

‘Agua?’ That had sounded like Latin – though the Classics were never my strong point. ‘Water,’ I replied.

Again the Morlock listened in silence, his head on a tilt.

So we continued. The Morlock pointed to common things – bits of clothing, or parts of the body like a head or a limb – and would come up with some candidate word. Some of his tries were frankly unrecognizable to me, and some of them sounded like German, or perhaps old English. And I would come back with my modern usage. Once or twice I tried to engage him in a longer conversation – for I could not see how this simple register of nouns was going to get us very far – but he stood there until I fell silent, and then continued with his patient matching game. I tried him with some of what I remembered of Weena’s language, that simplified, melodic tongue of two-word sentences; but again the Morlock stood patiently until I gave up.

This went on for several hours. At length, without ceremony, the Morlock took his leave – he walked off into the dark – I did not follow (Not yet! I told myself again). I ate and slept, and when I awoke he returned, and we resumed our lessons.

As he walked around my light cage, pointing at things and naming them, the Morlock’s movements were fluid and graceful enough, and his body seemed expressive; but I came to realize how much one relies, in day to day business, on the interpretation of the movements of one’s fellows. I could not read this Morlock in that way at all. It was impossible to tell what he was thinking or feeling – was he afraid of me? was he bored? – and I felt greatly disadvantaged as a result.

At the end of our second session of this, the Morlock stepped back from me.

He said: ‘That should be sufficient. Do you understand me?’

I stared at him, stunned by this sudden facility with my language! His pronunciation was blurred – that liquid Morlock voice is not designed, it seems, for the harsher consonants and stops of English – but the words were quite comprehensible.

When I did not reply, he repeated, ‘Do you understand me?’

‘I – yes. I mean: yes, I understand you! But how did you do this – how can you have learned my language – from so few words?’ For I judged we had covered a bare five hundred words, most of those concrete nouns and simple verbs.

‘I have access to records of all of the ancient languages of Humanity – as reconstructed – from Nostratic through the Indo-European group and its prototypes. A small number of key words is sufficient for the appropriate variant to be retrieved. You must inform me if anything I say is not intelligible.’

I took a cautious step forward. ‘Ancient? And how do you know I am ancient?’

Huge lids swept down over those goggled eyes. ‘Your physique is archaic. And the contents of your stomach, when analysed.’ He actually shuddered, evidently at the thought of the remnants of Mrs Watchets’s breakfast. I was astonished: I had a fastidious Morlock! He went on, ‘You are out of time. We do not yet understand how you came to arrive on the earth. But no doubt we will learn.’

‘And in the meantime,’ I said with some strength, ‘you keep me in this – this Cage of Light. As if I were a beast, not a man! You give me a floor to sleep on, and a pail for my toilet –’

The Morlock said nothing; he observed me, impassive.

The frustration and embarrassment which had assailed me since my arrival in this place welled up, now that I was able to express them, and I decided that sufficient pleasantries had been exchanged. I said, ‘Now that we can speak to each other, you’re going to tell me where on earth I am. And where you’ve hidden my machine. Do you understand that, fellow, or do I have to translate it for you?’ And I reached for him, meaning to grab at the hair clumps on his chest.

When I came within two paces of him, he raised his hand. That was all. I remember a queer green flash – I never saw the device he must have held, all the time he was near me – and then I fell to the Floor, quite insensible.

9

REVELATIONS AND REMONSTRANCES

I came to, spread-eagled on the Floor once more, and staring up into that confounded light.

I hoisted myself up onto my elbows, and rubbed my dazzled eyes. My Morlock friend was still there, standing just outside the circle of light. I got to my feet, rueful. These New Morlocks were going to be a handful for me, I realized.

The Morlock stepped into the light, its blue goggles glinting. As if nothing had interrupted our dialogue, he said, ‘My name is –’ his pronunciation reverted to the usual shapeless Morlock pattern – ‘Nebogipfel.’

‘Nebogipfel. Very well.’ In turn, I told him my name; within a few minutes he could repeat it with clarity and precision.

This, I realized, was the first Morlock whose name I had learned – the first who stood out from the masses of them I had encountered, and fought; the first to have the attributes of a distinguishable person.

‘So, Nebogipfel,’ I said. I sat cross-legged beside my trays, and rubbed at the rash of bruises my latest fall had inflicted on my upper arm. ‘You have been assigned as my keeper, here in this zoo.’

‘Zoo.’ He stumbled over that word. ‘No. I was not assigned. I volunteered to work with you.’

‘Work with me?’

‘I – we – want to understand how you came to be here.’

‘Do you, by Jove?’ I got to my feet and paced around my Cage of Light. ‘What if I told you that I came here in a machine that can carry a man through time?’ I held up my hands. ‘That I built such a machine, with these hands? What then, eh?’

He seemed to think that over. ‘Your era, as dated from your speech and physique, is very remote from ours. You are capable of achievements of high technology – witness your machine, whether or not it carries you through time as you claim. And the clothes you wear, the state of your hands, and the wear patterns of your teeth – all of these are indicative of a high state of civilization.’

‘I’m flattered,’ I said with some heat, ‘but if you believe I’m capable of such things – that I am a man, not an ape – why am I caged up in this way?’

‘Because,’ he said evenly, ‘you have already tried to attack me, with every intent of doing me harm. And on the Earth, you did great damage to –’

I felt fury burning anew. I stepped towards him. ‘Your monkeys were pawing at my machine,’ I shouted. ‘What did you expect? I was defending myself. I –’

He said: ‘They were children.’

His words pierced my rage. I tried to cling to the remnants of my self-justifying anger, but they were already receding from me. ‘What did you say?’

‘Children. They were children. Since the completion of the Sphere, the Earth is become a … nursery, a place for children to roam. They were curious about your machine. That is all. They would not have done you, or it, any conscious harm. Yet you attacked them, with great savagery.’

I stepped back from him. I remembered – now I let myself think about it – that the Morlocks capering ineffectually around my machine had struck me as smaller than those I’d encountered before. And they had made no attempt to hurt me … save only the poor creature who I had captured, and who had then nipped my hand – before I clubbed its face!

‘The one I struck. Did he – it – survive?’

‘The physical injuries were reparable. But –’

‘Yes?’

‘The inner scars, the scars of the mind – these may never heal.’

I dropped my head. Could it be true? Had I been so blinded by my loathing of Morlocks that I had been unable to see those creatures around the machine for what they were: not the rat-like, vicious creatures of Weena’s world – but harmless infants? ‘I don’t suppose you know what I’m talking about – but I feel as if I’m trapped in another one of those “Dissolving Views” …’

‘You are expressing shame,’ Nebogipfel said.

Shame … I never thought I should hear, and accept, such remonstrance from a Morlock! I looked at him, defiant. ‘Yes. Very well! And does that make me more than a beast, in your view, or less of one?’

He said nothing.

Even while I was confronting this personal horror, some calculating part of my mind was running over something Nebogipfel had said. Since the completion of the Sphere, the Earth is become a nursery …

‘What Sphere?’

‘You have much to learn of us.’

‘Tell me about the Sphere!’

‘It is a Sphere around the sun.’

Those seven simple words – startling! – and yet … Of course! The solar evolution I had watched in the time-accelerated sky, the exclusion of the sunlight from the Earth – ‘I understand,’ I said to Nebogipfel. ‘I watched the sphere’s construction.’

The Morlock’s eyes seemed to widen, in a very human mannerism, as he considered this unexpected news.

And now, for me, other aspects of my situation were becoming clear.

‘You said,’ I essayed to Nebogipfel, ‘“On the Earth, you did great damage –” Something on those lines.’ It was an odd thing to say, I thought now – if I was still on the Earth. I lifted my face and let the light beat down on me. ‘Nebogipfel – beneath my feet. What is visible, through this clear Floor?’

‘Stars.’

‘Not representations, not some kind of planetarium –’

‘Stars.’

I nodded. ‘And this light from above –’

‘It is sunlight.’

Somehow, I think I had known it. I stood in the light of a sun, which was overhead for twenty-four hours of every day; I stood on a Floor above the stars …

I felt as if the world were shifting about me; I felt light-headed, and there was a remote ringing in my ears. My adventures had already taken me across the deserts of time, but now – thanks to my capture by these astonishing Morlocks – I had been lifted across space. I was no longer on the Earth – I had been transported to the Morlocks’ solar Sphere!

10

A DIALOGUE WITH A MORLOCK

‘You say you travelled here on a Time Machine.’

I paced across my little disc of light, caged, restless. ‘The term is precise. It is a machine which can travel indifferently in any direction in time, and at any relative rate, as the driver determines.’

‘So you claim that you have journeyed here, from the remote past, on this machine – the machine found with you on the earth.’

‘Precisely!’ I snapped. The Morlock seemed content to stand, almost immobile, for long hours, as he developed his interrogation. But I am a man of a modern cut, and our moods did not coincide. ‘Confound it, fellow,’ I said, ‘you have observed yourself that I myself am of an archaic design. How else, but through time travel, can you explain my presence, here in the Year A.D. 657,208?’

Those huge curtain-eyelashes blinked slowly. ‘There are a number of alternatives: most of them more plausible than time travel.’

‘Such as?’ I challenged him.

‘Genetic resequencing.’

‘Genetic?’ Nebogipfel explained further, and I got the general drift. ‘You’re talking of the mechanism by which heredity operates – by which characteristics are transmitted from generation to generation.’

‘It is not impossible to generate simulacra of archaic forms by unravelling subsequent mutations.’

‘So you think I am no more than a simulacrum – reconstructed like the fossil skeleton of some Megatherium in a museum? Yes?’

‘There are precedents, though not of human forms of your vintage. Yes. It is possible.’

I felt insulted. ‘And to what purpose might I have been cobbled together in this way?’ I resumed my pacing around the Cage. The most disconcerting aspect of that bleak place was its lack of walls, and my constant, primeval sense that my back was unguarded. I would rather have been hurled in some prison cell of my own era – primitive and squalid, no doubt, but enclosed. ‘I’ll not rise to any such bait. That’s a lot of nonsense. I designed and built a Time Machine, and travelled here on it; and let that be an end to it!’

‘We will use your explanation as a working hypothesis,’ Nebogipfel said. ‘Now, please describe to me the machine’s operating principles.’

I continued my pacing, caught in a dilemma. As soon as I had realized that Nebogipfel was articulate and intelligent, unlike those Morlocks of my previous acquaintance, I had expected some such interrogation; after all, if a Time Traveller from Ancient Egypt had turned up in nineteenth century London I would have fought to be on the committee which examined him. But should I share the secret of my machine – my only advantage in this world – with these New Morlocks?

After some internal searching, I realized I had little choice. I had no doubt that the information could be forced out of me, if the Morlocks so desired. Besides, the construction of my machine was intrinsically simpler than that of, say, a fine clock. A civilization capable of throwing a shell around the sun would have little trouble reproducing the fruit of my poor lathes and presses! And if I spoke to Nebogipfel, perhaps I could put the fellow off while I sought some advantage from my difficult situation. I still had no idea where the machine was being held, still less how I should reach it and have a prospect of returning home.

But also – and here is the honest truth – the thought of my savagery among the child-Morlocks on the earth still weighed on my mind! I had no desire that Nebogipfel should think of me – nor the phase of Humanity which I, perforce, represented – as brutish. Therefore, like a child eager to impress, I wanted to show Nebogipfel how clever I was, how mechanically and scientifically adept: how far above the apes men of my type had ascended.

Still, for the first time I felt emboldened to make some demands of my own.

‘Very well,’ I said to Nebogipfel. ‘But first …’

‘Yes?’

‘Look here,’ I said, ‘the conditions under which you’re holding me are a little primitive, aren’t they? I’m not as young as I was, and I can’t do with this standing about all day. How about a chair? Is that so unreasonable a thing to ask for? And what about blankets to sleep under, if I must stay here?’

‘Chair.’ He had taken a second to reply, as if he was looking up the referent in some invisible dictionary.

I went on to other demands. I needed more fresh water, I said, and some equivalent of soap; and I asked – expecting to be refused – for a blade with which to shave my bristles.

For a time, Nebogipfel withdrew. When he returned he brought blankets and a chair; and after my next sleep period I found my two trays of provisions supplemented by a third, which bore more water.

The blankets were of some soft substance, too finely manufactured for me to detect any evidence of weaving. The chair – a simple upright thing – might have been of a light wood from its weight, but its red surface was smooth and seamless, and I could not scratch through its paint work with my fingernails, nor could I detect any evidence of joints, nails, screws or mouldings; it seemed to have been extruded as a complete whole by some unknown process. As to my toilet, the extra water came without soap, and nor would it lather, but the liquid had a smooth feel to it, and I suspected it had been treated with some detergent. By some minor miracle, the water was delivered warm to the touch – and stayed that way, no matter how long I let the bowl stand.

I was brought no blade, though – I was not surprised!

When next Nebogipfel left me alone, I undressed myself by stages and washed away the perspiration of some days, as well as lingering traces of Morlock blood; I also took the opportunity of rinsing through my underwear and shirt.

So my life in the Cage of Light became a little more civilized. If you imagine the contents of a cheap hotel room dumped into the middle of the floor of some vast ball room, you will have the picture of how I was living. When I pulled together the chair, trays and blankets I had something of a cosy nest, and I did not feel quite so exposed; I took to placing my jacket-pillow under the chair, and so sleeping with my head and shoulders under the protection of this little fastness. Most of the time I was able to dismiss the prospect of stars beneath my feet – I told myself that the lights in the Floor were some elaborate illusion – but sometimes my imagination would betray me, and I would feel as if I were suspended over an infinite drop, with only this insubstantial Floor to save me.

All this was quite illogical, of course; but I am human, and must needs pander to the instinctive needs and fears of my nature!

Nebogipfel observed all this. I could not tell if his reaction was curiosity or confusion, or perhaps something more aloof – as I might have watched the antics of a bird in building a nest, perhaps.

And in these circumstances, the next few days wore away – I think four or five – as I strove to describe to Nebogipfel the workings of my Time Machine – and as well seeking subtly to extract from him some details of this History in which I had landed myself.

I described the researches into physical optics which had led me to my insights into the possibility of time travel.

‘It is becoming well known – or was, in my day – that the propagation of light has anomalous properties,’ I said. ‘The speed of light in a vacuum is extremely high – it travels hundreds of thousands of miles each second – but it is finite. And, more important, as demonstrated most clearly by Michelson and Morley a few years before my departure, this speed is isotropic … ’

I took some care to explain this rum business. The essence of it is that light, as it travels through space, does not behave like a material object, such as an express train.