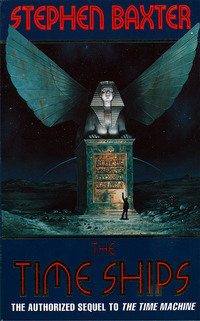

The Time Ships

I asked Nebogipfel how the Morlocks governed themselves.

He explained to me – in a somewhat patronizing manner, I thought – that the Sphere was a large enough place for several ‘nations’ of Morlocks. These ‘nations’ were distinguished mainly by the mode of government they chose. Almost all had some form of democratic process in place. In some areas a representative parliament was selected by a Universal Suffrage, much along the lines of our own Westminster Parliament. Elsewhere, suffrage was restricted to an elite sub-group, composed of those considered especially capable, by temperament and training, of governance: I think the nearest models in our philosophy are the classical republics, or perhaps the ideal form of Republic imagined by Plato; and I admit that this approach appealed to my own instincts.

But in most areas, the machinery of the Sphere had made possible a form of true Universal Suffrage, in which the inhabitants were kept abreast of current debates by means of the blue windows in their partitions, and then instantly registered their preferences on each issue by similar means. Thus, governance proceeded on a piecemeal basis, with every major decision subject to the collective whim of the populace.

I felt distrustful of such a system. ‘But surely there are some in the population who cannot be empowered with such authority! What about the insane, or the feeble-minded?’

He considered me with a certain stiffness. ‘We have no such weaknesses.’

I felt like challenging this Utopian – even here, in the heart of his Utopia! ‘And how do you ensure that?’

He did not answer me immediately. Instead, he went on, ‘Each member of our adult population is rational, and able to make decisions on behalf of others – and is trusted to do so. In such circumstances, the purest form of democracy is not only possible, it is advisable – for many minds combine to produce decisions superior to those of one.’

I snorted. ‘Then what of all these other Parliaments and Senates you have described?’

‘Not everyone agrees that the arrangements in this part of the Sphere are ideal,’ he said. ‘Is that not the essence of freedom? Not all of us are sufficiently interested in the mechanics of governance to wish to participate; and for some, the entrusting of power to another through representation – or even without any representation at all – is preferable. That is a valid choice.’

‘Fine. But what happens when such choices conflict?’

‘We have room,’ he said heavily. ‘You must not forget that fact; you are still dominated by planet-bound expectations. Any dissenter is free to depart, and to establish a rival system elsewhere …’

These ‘nations’ of the Morlocks were fluid things, with individuals joining and leaving as their preferences evolved. There was no fixed territory or possessions, nor even any fixed boundaries, as far as I could make out; the ‘nations’ were mere groupings of convenience, clusterings across the Sphere.

There was no war among the Morlocks.

It took me some time to believe this, but at last I was convinced. There were no causes for war. Thanks to the mechanisms of the Floor there was no shortage of provision, so no ‘nation’ could argue for goals of economic acquisition. The Sphere was so huge that the empty land available was almost unlimited, so that territorial conflicts were meaningless. And – most crucially – the Morlocks’ heads were free of the canker of religion, which has caused so much conflict through the centuries.

‘You have no God, then,’ I said to Nebogipfel, with something of a thrill: though I have some religious tendencies myself, I imagined shocking the clerics of my own day with an account of this conversation!

‘We have no need of a God,’ Nebogipfel retorted.

The Morlocks regarded a religious set of mind – as opposed to a rational state – as a hereditable trait, with no more intrinsic meaning than blue eyes or brown hair.

The more Nebogipfel outlined this notion, the more sense it made to me.

What notion of God has survived through all of Humanity’s mental evolution? Why, precisely the form it might suit man’s vanity to conjure up: a God with immense powers, and yet still absorbed in the petty affairs of man. Who could worship a chilling God, even if omnipotent, if He took no interest whatsoever in the flea-bite struggles of humans?

One might imagine that, in any conflict between rational humans and religious humans, the rational ought to win. After all, it is rationality that invented gunpowder! And yet – at least up to our nineteenth century – the religious tendency has generally won out, and natural selection operated, leaving us with a population of religiously-inclined sheep – it has sometimes seemed to me – capable of being deluded by any smooth-tongued preacher.

The paradox is explained because religion provides a goal for men to fight for. The religious man will soak some bit of ‘sacred’ land with his blood, sacrificing far more than the land’s intrinsic economic or other value.

‘But we have moved beyond this paradox,’ Nebogipfel said to me. ‘We have mastered our inheritance: we are no longer governed by the dictates of the past, either as regards our bodies or our minds …’

But I did not follow up this intriguing notion – the obvious question to ask was, ‘In the absence of a God, then, what is the purpose of all of your lives?’ – for I was entranced by the idea of how Mr Darwin, with all his modern critics in the Churches, would have loved to have witnessed this ultimate triumph of his ideas over the Religionists!

In fact – as it turned out – my understanding of the true purpose of the Morlocks’ civilization would not come until much later.

I was impressed, though, with all I saw of this artificial world of the Morlocks – I am not sure if my respectful awe has been reflected in my account here. This brand of Morlock had indeed mastered their inherited weaknesses; they had put aside the legacy of the brute – the legacy bequeathed by us – and had thereby achieved a stability and capability almost unimaginable to a man of 1891: to a man like me, who had grown up in a world torn apart daily by war, greed and incompetence.

And this mastery of their own nature was all the more striking for its contrast with those other Morlocks – Weena’s Morlocks – who had, quite obviously, fallen foul of the brute within, despite their mechanical and other aptitudes.

14

CONSTRUCTIONS AND DIVERGENCES

I discussed the construction of the Sphere with Nebogipfel. ‘I imagine great engineering schemes which broke up the giant planets – Jupiter and Saturn – and –’

‘No,’ Nebogipfel said. ‘There was no such scheme; the primal planets – from the earth outward – still orbit the sun’s heart. There would not have been sufficient material in all the planets combined even to begin the construction of such an entity as this Sphere.’

‘Then how –?’

Nebogipfel described how the sun had been encircled by a great fleet of space-faring craft, which bore immense magnets of a design – involving electrical circuits whose resistance was somehow reduced to zero – I could not fathom. The craft circled the sun with increasing speed, and a belt of magnetism tightened around the sun’s million-mile midriff. And – as if that great star were no more than a soft fruit, held in a crushing fist – great founts of the sun’s material, which is itself magnetized, were forced away from the equator to gush from the star’s poles.

More fleets of space-craft then manipulated this huge cloud of lifted material, forming it at last into an enclosing shell; and the shell was then compressed, using shaped magnetic fields once more, and transmuted into the solid structures I saw around me.

The enclosed sun still shone, for even the immense detached masses required to construct this great artefact were but an invisible fraction of the sun’s total bulk; and within the Sphere, sunlight shone perpetually over giant continents, each of which could have swallowed millions of splayed-out earths.

Nebogipfel said, ‘A planet like the earth can intercept only an invisible fraction of the sun’s output, with the rest disappearing, wasted, into the sink of space. Now, all of the sun’s energy is captured by the enclosing Sphere. And that is the central justification for constructing the Sphere: we have harnessed a star …’

In a million years, Nebogipfel told me, the Sphere would capture enough additional solar material to permit its thickening by one-twenty-fifth of an inch – an invisibly small layer, but covering a stupendous area! The solar material, transformed, was used to further the construction of the Sphere. Meanwhile, some solar energy was harnessed to sustain the Interior of the Sphere and to power the Morlocks’ various projects.

With some excitement, I described what I had witnessed during my journey through futurity: the brightening of the sun, and that jetting at the poles – and then how the sun had disappeared into blackness, as the Sphere was thrown around it.

Nebogipfel regarded me, I fancied with some envy. ‘So,’ he said, ‘you did indeed watch the construction of the Sphere. It took ten thousand years …’

‘But to me on my machine, no more than heartbeats passed.’

‘You have told me that this is your second voyage into the future. And that during your first, you saw differences.’

‘Yes.’ Now I confronted that perplexing mystery once more. ‘Differences in the unfolding of History … Nebogipfel, when I first journeyed to the future, your Sphere was never built.’

I summarized to Nebogipfel how I had formerly travelled far beyond this year of A.D. 657,208. During that first voyage, I had watched the colonization of the land by a tide of rich green, as winter was abolished from the earth and the sun grew unaccountably brighter. But – unlike my second trip – I saw no signs of the regulation of the earth’s axial tilt, nor did I witness anything of the slowing of its rotation. And, most dramatic, without the construction of the sun-shielding Sphere, the earth had remained fair, and had not been banished into the Morlocks’ Stygian darkness.

‘And so,’ I told Nebogipfel, ‘I arrived in the year A.D. 802,701 – a hundred and fifty thousand years into your future – yet I cannot believe, if I had travelled on so far this time, that I should find the same world again!’

I summarized to Nebogipfel what I had seen of Weena’s world, with its Eloi and degraded Morlocks. Nebogipfel thought this over. ‘There has been no such state of affairs in the evolution of Humanity, in all of recorded History – my History,’ he said. ‘And since the Sphere, once constructed, is self-sustaining, it is difficult to imagine that such a descent into barbarism is possible in our future.’

‘So there you have it,’ I agreed. ‘I have journeyed through two, quite exclusive, versions of History. Can History be like unfired clay, able to be remade?’

‘Perhaps it can,’ Nebogipfel murmured. ‘When you returned to your own era – to 1891 – did you bring any evidence of your travels?’

‘Not much,’ I admitted. ‘But I did bring back some flowers, pretty white things like mallows, which Weena – which an Eloi had placed in my pocket. My friends examined them. The flowers were of an order they couldn’t recognize, and I remember how they remarked on the gynoecium …’

‘Friends?’ Nebogipfel said sharply. ‘You left an account of your journey, before embarking once more?’

‘Nothing written. But I did give some friends a fullish account of the affair, over dinner.’ I smiled. ‘And if I know one of that circle, the whole thing was no doubt written up in the end in some popularized and sensational form – perhaps presented as fiction …’

Nebogipfel approached me. ‘Then there,’ he said to me, his quiet voice queerly dramatic, ‘there is your explanation.’

‘Explanation?’

‘For the Divergence of Histories.’

I faced him, horrified by a dawning comprehension. ‘You mean that with my account – my prophecy – I changed History?’

‘Yes. Armed with that warning, Humanity managed to avoid the degradation and conflict that resulted in the primitive, cruel world of Eloi and Morlock. Instead, we continued to grow; instead, we have harnessed the sun.’

I felt quite unable to face the consequences of this hypothesis – although its truth and clarity struck me immediately. I shouted, ‘But some things have stayed the same. Still you Morlocks skulk in the dark!’

‘We are not Morlocks,’ Nebogipfel said softly. ‘Not as you remember them. And as for the dark – what need have we of a flood of light? We choose the dark. Our eyes are fine instruments, capable of revealing much beauty. Without the brutal glare of the sun, the full subtlety of the sky can be discerned …’

I could find no distraction in goading Nebogipfel, and I had to face the truth. I stared down at my hands – great battered things, scarred with decades of labour. My sole aim, to which I had devoted the efforts of these hands, had been to explore time! – to determine how things would come out on the cosmological scale, beyond my own few mayfly decades of life. But, it seemed, I had succeeded in far more.

My invention was much more powerful than a mere time-travelling machine: it was a History Machine, a destroyer of worlds!

I was a murderer of the future: I had taken on, I realized, more powers than God himself (if Aquinas is to be believed). By my twisting-up of the workings of History, I had wiped over billions of unborn lives – lives that would now never come to be.

I could hardly bear to live with the knowledge of this presumption. I have always been distrustful of personal power – for I have met not one man wise enough to be entrusted with it – but now, I had taken to myself more power than any man who had ever lived!

If I should ever recover my Time Machine – I promised myself then – I would return into the past, to make one final, conclusive adjustment to History, and abolish my own invention of the infernal device.

… And I realized now that I could never retrieve Weena. For, not only had I caused her death – now, it turned out, I had nullified her very existence!

Through all this turmoil of the emotions, the pain of that little loss sounded sweet and clear, like the note of an oboe in the midst of the clamour of some great orchestra.

15

LIFE AND DEATH AMONG THE MORLOCKS

One day, Nebogipfel led me to what was, perhaps, the most disquieting thing I saw in all my time in that city-chamber.

We approached an area, perhaps a half-mile square, where the partitions seemed lower than usual. As we neared, I became aware of a rising level of noise – a babble of liquid throats – and a sharply increased smell of Morlock, of their characteristic musty, sickly sweetness. Nebogipfel bade me pause on the edge of this clearing.

Through my goggles I was able to see that the surface of the cleared-out area was alive – it pulsated – with the mewling, wriggling, toddling form of babies. There were thousands of them, these tumbling Morlock infants, their little hands and feet pawing at each other’s clumps of untidy hair. They rolled, just like young apes, and poked at junior versions of the informative partitions I have described elsewhere, or crammed food into their dark mouths; here and there, adults walked through the crowd, raising one who had fallen here, untangling a miniature dispute there, soothing a wailing infant beyond.

I gazed out over this sea of infants, bemused. Perhaps such a collection of human children might be found appealing by some – not by me, a confirmed bachelor – but these were Morlocks … You must remember that the Morlock is not an attractive entity to human sensibilities, even as a child, with his worm-pallor flesh, his coolness to the touch, and that spider-webbing of hair. If you think of a giant tabletop covered in wriggling maggots, you will have something of my impression as I stood there!

I turned to Nebogipfel. ‘But where are their parents?’

He hesitated, as if searching for the right phrase. ‘They have no parents. This is a birth farm. When old enough, the infants will be transported from here to a nursery community, either on the Sphere or …’

But I had stopped listening. I glanced at Nebogipfel, up and down, but his hair masked the form of his body.

With a jolt of wonder, I saw now another of those facts which had stared me in the eyeball since my arrival here, but which I was too clever by far to perceive: there was no evidence of sexual discrimination – not in Nebogipfel, nor in any of the Morlocks I had come across – not even in those, like my low-gravity visitors, whose bodies were sparsely coated with hair, and so easier to make out. Your average Morlock was built like a child, undifferentiated sexually, with the same lack of emphasis on hips or chest … I realized with a shock that I knew nothing of – nor had I thought to question – the Morlocks’ processes of love and birth!

Nebogipfel told me something now of the rearing and education of the Morlock young.

The Morlock began his life in these birth farms and nursery communities – the whole of the Earth, to my painful recollection, had been given over to one such – and there, in addition to the rudiments of civilized behaviour, the youngster was taught one essential skill: the ability to learn. It is as if a schoolboy of the nineteenth century – instead of having drummed into his poor head a lot of nonsense about Greek and Latin and obscure geometric theorems – had been taught, instead, how to concentrate, and to use libraries, and the mechanisms of how to assimilate knowledge – how, above all, to think. After that, the acquisition of any specific knowledge depended on the needs of the task in hand, and the inclination of the individual.

When Nebogipfel summarized this to me, its simplicity of logic struck me with an almost physical force. Of course! – I said to myself – so much for schools! What a contrast to the battleground of Ignorance with Incompetence that made up my own, unlamented schooldays!

I was moved to ask Nebogipfel about his own profession.

He explained to me that once the date of my origin had been fixed, he had made himself into something of an expert in my period and its mores from the records of his people; and he had become aware of several significant differences between the ways of our races.

‘Our occupations are not as consuming as yours,’ he said. ‘I have two loves – two vocations.’ His eyes were invisible, making his emotions even more impossible to read. He said: ‘Physics, and the training of the young.’

Education, and training of all sorts, continued throughout a Morlock’s lifetime, and it was not unusual for an individual to pursue three or four ‘careers’, as we might call them, in sequence, or even in parallel. The general level of intelligence of the Morlocks was, I got the impression, rather higher than that of the people of my own century.

Still, Nebogipfel’s choice of vocations startled me; I had thought that Nebogipfel must specialize solely in the physical sciences, such was his ability to follow my sometimes rambling accounts of the theory of the Time Machine, and the evolution of History.

‘Tell me,’ I said lightly, ‘for which of your talents were you appointed to supervise me? Your expertise in physics – or your nannying skills?’

I thought his black, small-toothed mouth stretched in a grin.

Then the truth struck me – and I felt a certain humiliation burn in me at the thought. I am an eminent man of my day, and yet I had been put in the charge of one more suited to shepherding children!

… And yet, I reflected now, what was my blundering about, when I first arrived in the Year 657,208, but the actions of a comparative child?

Now Nebogipfel led me to a corner of the nursery area. This special place was covered by a structure about the size and shape of a small conservatory, done out in the pale, translucent material of the Floor – in fact, this was one of the few parts of that city-chamber to be covered over in any way. Nebogipfel led me inside the structure. The shelter was empty of furniture or apparatus, save for one or two of the partitions with glowing screens which I had noticed elsewhere. And, in the centre of the Floor, there was what looked like a small bundle – of clothing, perhaps – being extruded from the glass.

The Morlocks who attended here had a more serious bent than those who supervised the children, I perceived. Over their pale hair they wore loose smocks – vest-like garments with many pockets – crammed with tools which were mostly quite incomprehensible to me. Some of the tools glowed faintly. This latest class of Morlock had something of the air of the engineer, I thought: it was an odd attribute in this sea of babies; and, although they were distracted by my clumsy presence, the engineers watched the little bundle on the Floor, and passed instruments over it periodically.

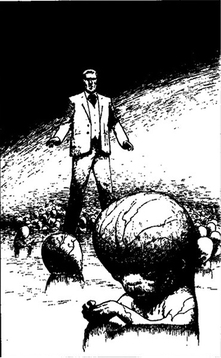

My curiosity engaged, I stepped towards that central bundle. Nebogipfel hung back, letting me proceed alone. The thing was only a few inches long, and was still half-embedded in the glass, like a sculpture being hewn from some rocky surface. In fact it did look a little like a statue: here were the buds of two arms, I thought, and there was what might become a face – a disc coated with hair, and split by a thin mouth. The bundle’s extrusion seemed slow, and I wondered what was so difficult for the hidden devices about manufacturing this particular artefact. Was it especially complex, perhaps?

And then – it was a moment which will haunt me as long as I live – that tiny mouth opened. The lips parted with a soft popping sound, and a mewling, fainter than that of the tiniest kitten, emerged to float on the air; and the miniature face crumpled, as if in some mild distress.

I stumbled backwards, as shocked as if I had been punched.

Nebogipfel seemed to have anticipated something of my distress. He said, ‘You must remember that you are dislocated in Time by a half million years: the interval between us is ten times the age of your species …’

‘Nebogipfel – can it be true? That your young – you yourself – are extruded from this Floor, manufactured with no more majesty than a cup of water?’ The Morlocks had indeed ‘mastered their genetic inheritance’, I thought – for they had abolished gender, and done away with birth.

‘Nebogipfel,’ I protested, ‘this is – inhuman.’

He tilted his head; evidently the word meant nothing to him. ‘Our policy is designed to optimize the potential of the human form – for we are human too,’ he said severely. ‘That form is dictated by a sequence of a million genes, and so the number of possible human individuals – while large – is finite. And all of these individuals may be –’ he hesitated ‘– imagined by the Sphere’s intelligence.’

Sepulture, he told me, was also governed by the Sphere, with the abandoned bodies of the dead being passed into the Floor without ceremony or reverence, for the dismantling and reuse of their materials.

‘The Sphere assembles the materials required to give the chosen individual life, and –’

‘“Chosen”?’ I confronted the Morlock, and the anger and violence which I had excluded from my thoughts for so long flooded back into my soul. ‘How very rational. But what else have you rationalized out, Morlock? What of tenderness? What of love?’

‘And then – it was a moment which will haunt me as long as I live – that tiny mouth opened.’