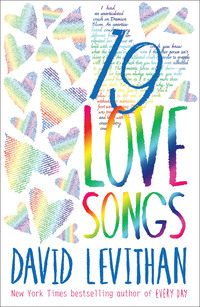

19 Love Songs

Damien nodded and drank some more punch. “She’s always so serious,” he agreed.

The punch was turning our lips cherry red.

“Let’s get out of here,” I said.

“Okay.”

We were alone together in an unknown hotel in an unknown city. So we did the natural thing.

We went to his room.

And we watched TV.

It was his room, so he got to choose. We ended up watching The Departed on basic cable. It was, I realized, the most time we had ever spent alone together. He lay back on his bed and I sat on Sung’s, making sure my angle was such that I could watch Damien as much as I watched the TV.

During the first commercial break, I asked, “Is something wrong?”

He looked at me strangely. “No. Does it seem like something’s wrong?”

I shook my head. “No. Just asking.”

During the second commercial break, I asked, “Were you and Julie going out?”

He put his head back on his pillow and closed his eyes.

“No.” And then, about a minute later, right before the movie started again, “It wasn’t anything, really.”

During the third commercial break, I asked, “Does she know that?”

“What?”

“Does Julie know it wasn’t anything?”

“No,” he said. “It looks like she doesn’t know that.”

This was it, I was sure—the point where he’d ask for my advice. I could help him. I could prove myself worthy of his company.

But he let it drop. He didn’t want to talk about it. He wanted to watch the movie.

I realized he needed to reveal himself to me in his own time. I couldn’t rush it. I had to be patient. For the remaining commercial breaks, I made North Dakota jokes. He laughed at some of them, and even threw in a few of his own.

Sung came back when there were about fifteen minutes left in the movie. I could tell he wasn’t thrilled about me sitting on his bed, but I wasn’t about to move.

“Sung,” I told him, “if this whole quiz bowl thing doesn’t work out for you, I think you have a future in disco.”

“Shut up,” he grumbled, taking off the famous jacket and hanging it in the closet.

We watched the rest of the movie in silence, with Sung sitting on the edge of Damien’s bed. As soon as the credits were rolling, Sung announced it was time to go to sleep.

“But where are you sleeping?” I asked, spreading out on his sheets.

“That’s my bed,” he said.

I wanted to offer Sung a swap—he could stay with Wes and talk about polynomials all night, while I could stay with Damien. But clearly that wasn’t a real option. Damien walked me to the door.

“Lay off the minibar,” he said. “We need you sober tomorrow.”

“I’ll try,” I replied. “But those little bottles are just so pretty. Every time I drink from them, I can pretend I’m a doll.”

He chuckled and hit me lightly on the shoulder.

“Resist,” he commanded.

Again, I told him I’d try.

Wes was in bed and the lights were off when I got to my room, so I very quietly changed into my pajamas and brushed my teeth.

I was about to nod off when Wes’s voice asked, “Did you have fun?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Damien and I went to his room and watched The Departed. It was a good time. We looked for you, but you were already gone.”

“That social sucked.”

“It most certainly did.”

I closed my eyes.

“Goodnight,” Wes said softly, making it sound like a true wish. Nobody besides my parents had ever said it to me like that before.

“Goodnight,” I said back. Then I made sure he’d plugged the clock back in, and went to sleep.

The next morning, we kicked North Dakota’s ass. Then, for good measure, we erased Maryland from the boards and made Oklahoma cry.

It felt good.

“Don’t get too cocky,” Sung warned us, which was pretty precious, since Sung was the cockiest of us all. I half expected “We Are the Champions” to come blaring out of his ears every time we won a round.

Our fourth and last match of the day—in the quarterfinals—was against the team from Clearwater, Florida, which had made it to the finals for each of the past ten years, winning four of those times. They were legendary, insofar as people like Sung had heard about them and had studied their strategies, with some tapes Mr. Phillips had managed to get off Clearwater local access.

Even though I was the alternate, I was put in the starting lineup. Clearwater was known for treating the canon like a cannon to demolish the other team.

“Bring it on,” I said.

It soon became clear who my counterpart on the Clearwater team was—a wispy girl with straight brown hair who could barely bother to put down her Muriel Spark in order to start playing. The first time she opened her mouth, she revealed their secret weapon:

She was British.

Frances looked momentarily frightened by this, but I took it in stride. When the girl lunged with Byron, I parried with Asimov. When she volleyed with Burgess, I pounced with Roth. Neither of us missed a question, so it became a test of buzzer willpower. I started to ring in a split second before I knew the answer. And I always knew the answer.

Until I did the unthinkable.

I buzzed in for a science question.

Which Nobel Prize winner later went on to write The Double Helix and Avoid Boring People?

I realized immediately it wasn’t Saul Bellow or Kenzaburo Oe.

As the judge said, “Do you have an answer?” the phrase The Double Helix hit in my head.

“Crick!” I exclaimed.

The judge looked at me for a moment, then down at his card. “That is incorrect. Clearwater, which Nobel Prize winner later went on to write The Double Helix and Avoid Boring People ?”

It was not the lit girl who buzzed in.

“James D. Watson,” one of the math boys answered snottily, the D sent as a particular fuck you to me.

“Sorry,” I whispered to my team.

“It’s okay,” Damien said.

“No worries,” Wes said.

Sung, I knew, wouldn’t be as forgiving.

I was now off my game and more cautious with the buzzer, so Brit girl got the best of me on Caliban and Vivienne Haigh-Wood. I managed to stick One Hundred Years of Solitude in edgewise, but that was scant comfort. I mean, who didn’t know One Hundred Years of Solitude ?

Clearwater had a one-question lead with three questions left, and the last questions were about math, history, and geography. So I sat back while Sung rocked the relative areas of a rhombus and a circle, Wes sent a little love General Omar Bradley’s way, and Frances wrapped it up with Tashkent, which I had not known was the capital of Uzbekistan, its name translating as “stone village.”

Usually we burst out of our chairs when we won, but this match had been so exhausting that we could only feel relieved. We shook hands with the other team—Brit girl’s hand felt like it was made of paper, which I found weird.

After Clearwater had left the room, Sung called an emergency team meeting.

“That was too close,” he said. Not congratulations or nice work.

No, Sung was pissed.

He talked about the need to be more aggressive on the buzzer, but also to exercise care. He said we should always play to our strengths. To make a blunder was to destroy the fabric of our entire team.

“I get it, I get it,” I said.

“No,” Sung told me, “I don’t think you do.”

“Sung,” Mr. Phillips cautioned.

“I think he needs to hear this,” Sung insisted. “From the very start of the year, he has refused to be a team player. And what we saw today was nothing short of an insurrection. He broke the unwritten rules.”

“He is standing right here,” I pointed out. “Just come right out and say it.”

“YOU ARE NOT TO ANSWER SCIENCE QUESTIONS!” Sung yelled. “WHAT WERE YOU THINKING?”

“Hey—” Damien started to interrupt.

I held up my hand. “No, it’s okay. Sung needs to get this out of his system.”

“You are the alternate,” Sung went on.

“You don’t seem to mind it when I’m answering questions, Sung.”

“We only have you here because we have to!”

“That’s enough,” Mr. Phillips said decisively.

“No, it’s not enough,” I said. “I’m sick of you all acting like I’m this English freak raining on your little math-science parade. Sung seems to think my contribution to this team is a little less than everyone else’s.”

“Anyone can memorize book titles!” Sung shouted.

“Oh, please. Like I care what you think? You don’t even know the difference between Keats and Byron.”

“The difference between Keats and Byron doesn’t matter!”

“None of this matters!” I shouted back. “Don’t you get it, Sung? NONE OF THIS MATTERS. Yes, you have knowledge—but you’re not doing anything with it. You’re reciting it. You’re not out curing cancer—you’re listing the names of the people who’ve tried to cure cancer. This whole thing is a joke, Captain. It’s trivial. Which is why everyone laughs at us.”

“You think we’re all trivial?” Sung challenged.

“No,” I said. “I think you’re trivial with your quiz bowl obsession. The rest of us have other things going on. We have lives.”

“You’re the one who’s not a part of our team! You’re the outcast!”

“If that’s so true, Sung, then why are you the only one of us wearing a fucking varsity jacket? Why do you think nobody else wanted to be seen in one? It’s not just me, Sung. It’s all of us.”

“Enough!” Mr. Phillips yelled.

Sung looked like he wanted to kill me. And I knew at the same time that he’d never look at that damn jacket the same way again.

“Why don’t we all take a break over dinner,” Mr. Phillips went on, “then regroup in my room at eight for a scrimmage before the semifinals tomorrow morning? I don’t know who we’re facing, but we’re going to need to be a team to face them.”

What we did next wasn’t very teamlike: Mr. Phillips, a brooding Sung, Frances, and Gordon went one way for dinner, while Wes, Damien, and I went another way.

“There’s a Steak ’n Shake a few blocks away,” Wes told us.

“Sounds good,” Damien said.

I, brooding as well, followed.

“It was a question about books,” I said, once we’d left the hotel. “I didn’t realize it was a science question.”

“Crick wasn’t that far off,” Wes pointed out.

“Yeah, but I still fucked it up.”

“And we still won,” Damien said.

Yeah, I knew that.

But I wasn’t feeling it.

Damien and Wes tried to cheer me up. Not just by getting my burger and shake for me, but by sitting across from me and treating me like a friend.

“So how does it feel to be the Quiz Bowl Antichrist?” Damien asked in a mock-sportscaster voice, holding an invisible microphone out for my reply.

“Well, as James D. Watson said, I’m the motherfuckin’ princess. All other quiz bowlers shall bow down to me. Because you know what?”

“What?” Damien and Wes both asked.

“One of these days, I’m going to be the goddamn answer to a quiz bowl question.”

“Yeah,” Wes said. “ ‘What quiz bowl alternate murdered his team captain in the semifinals and later wrote a book, Among Boring People ?’ ”

Damien shook his head. “Not funny. There will be no murder tonight or tomorrow.”

“Do you realize, if we win this thing, it’s going to come up on Google Search for the rest of our lives?” I said.

“Let’s wear masks in the photo,” Wes suggested.

“I’ll be Michelangelo. You can be Donatello.”

And it went on like this for a while. Damien stopped talking and watched me and Wes going back and forth. I was talking, but mostly I was watching him back. The green-blue of his eyes. The side of his neck. The curl of hair that dangled over the left corner of his forehead. No matter where I looked, there was something to see.

I didn’t have any control over it. Something inside of me was shifting. Everything I’d refused to articulate was starting to spell itself out. Not as knowledge, but as the impulse beneath the knowledge. I knew I wanted to be with him, and I was also starting to feel why. He was a reason I was here. He was a reason it mattered.

I was talking to Wes, but really I was talking to Damien through what I was saying to Wes. I wanted him to find me entertaining. I wanted him to find me interesting. I wanted him to find me.

We were done pretty quickly, and before I knew it, we were walking back to the Westin. Once we got to the lobby, Wes magically decided to head back to our room until the “scrimmage” at eight. That left Damien and me with two hours and nothing to do.

“Why don’t we go to my room?” Damien suggested.

I didn’t argue. I started to feel nervous—unreasonably nervous. We were just two friends going to a room. There wasn’t anything else to it. And yet . . . he hadn’t mentioned watching TV, and last time he’d said, “Why don’t we go to my room to watch TV?”

“I’m glad it’s just the two of us,” I ventured.

“Yeah, me too,” Damien said.

We rode the elevator in silence and walked down the hallway in silence. When we got to his door, he swiped his electronic key in the lock and got a green light on the first try. I could never manage to do that.

“After you,” he said, opening the door and gesturing me in.

I walked forward, down the small hallway, turning toward the beds. And that’s when I realized—there was someone in the room. And it was Sung. And he was on his bed. And he wasn’t wearing his jacket. Or a shirt. And he was moaning a little.

I thought we’d caught him jerking off. I couldn’t help it—I burst out laughing. And that’s what made him notice we were in the room. He jumped and turned around, and I realized Frances was in the bed with him, shirt also off, but bra still on.

It was all so messed up that I couldn’t stop laughing. Tears were coming to my eyes.

“Get out!” Sung yelled.

“I’m sorry, Frances,” I said between laughing fits. “I’m so sorry.”

“GET OUT!” Sung screamed again, standing up now. Thank God he still had his pants on. “YOU ARE THE DEVIL. THE DEVIL!”

“I prefer Antichrist,” I told him.

“THE DEVIL!”

“THE DEVIL!” I mimicked back.

I felt Damien’s hand on my shoulder. “Let’s go,” he whispered.

“This is so pathetic,” I said. “Sung, man, you’re pathetic.”

Sung lunged forward then, and Damien stepped in between us.

“Go,” Damien told me. “Now.”

I was laughing again, so I apologized to Frances again, then I pulled myself into the hallway.

Damien came out a few seconds later and closed the door behind us.

“Holy shit!” I said.

“Stop it,” Damien said. “Enough.”

“Enough?” I laughed again. “I haven’t even started.”

Damien shook his head. “You’re cold, man,” he said. “I can’t believe how cold you are.”

“What?” I asked. “You don’t find this funny?”

“You have no heart.”

This sobered me up pretty quickly. “How can you say that?” I asked. “How can you, of all people, say that?”

“What does that mean? Me, of all people?”

He’d gotten me.

“Alec?”

“I don’t know!” I shouted. “Okay? I don’t know.”

This sounded like the truth, but it was feeling less than that. I knew. Or I was starting to know.

“I do have a heart,” I said. But I stopped there.

I could feel it all coming apart. The collapse of all those invisible plans, the appearance of all those hidden thoughts.

I bolted. I left him right there in the hallway. I didn’t wait for the elevator—I hit the emergency stairs. I ran like I was the one on the cross-country team, even when I heard him following me.

“Don’t!” I yelled back at him.

I got to my floor and ran to my room. The card wouldn’t work the first time, and I nervously looked at the stairway exit, waiting for him to show up. But he must’ve stopped. He must’ve heard. I got the key through the second time.

Wes was on his bed, reading a comic.

“You’re back early,” he said, not looking up.

I couldn’t say a thing. There was a knock on the door. Damien calling out my name.

“Don’t answer it,” I said. “Please, don’t answer it.”

I locked myself in the bathroom. I stared at the mirror.

I heard Wes murmur something to Damien through the door without opening it. Then he was at the bathroom door.

“Alec? Are you okay?”

“I’m fine,” I said, but my voice was soggy coming out of my throat.

“Open up.”

I couldn’t. I sat on the lip of the tub, breathing in, breathing out. I remembered the look on Sung’s face and started to laugh. Then I thought of Frances lying there and felt sad. I wondered if I really didn’t have a heart.

“Alec,” Wes said again, gently. “Come on.”

I waited until he walked off. Then I opened the door and went into the bedroom. He was back on his bed, but he hadn’t picked up the comic. He was sitting at the edge, waiting for me.

I told him what had happened. Not the part about Damien, at first, but the part about Sung and Frances. He didn’t laugh, and neither did I. Then I told him Damien’s reaction to my reaction, without going into what was underneath.

“Do you think I’m cold?” I asked him. “Really—am I?”

“You’re not cold,” he said. “You’re just so angry.”

I must’ve looked surprised by this. He went on.

“You can be a total prick, Alec. There’s nothing wrong with that—all of us can be total pricks. We like to think that just because we’re geeks, we can’t be assholes. But we can be. Most of the time, though, it’s not coming from meanness or coldness. It’s coming from anger. Or sadness. I mean, I see people like me and I just want to rip them apart.”

“But why do I want to rip Sung apart?”

“I don’t know. Because he’s a prick, too. And maybe you feel if you rip apart the quiz bowl geek, no one will think of you as a quiz bowl geek.”

“But I’m not a quiz bowl geek!”

“Haven’t you figured it out yet?” Wes asked. “Nobody’s a quiz bowl geek. We’re all just people. And you’re right—what we do here has no redeeming social value whatsoever. But it can be an interesting way to pass the time.”

I sat down on my bed, facing Wes so that our knees almost touched.

“I’m not a very happy person,” I told him. “But sometimes I can trick myself into thinking I am.”

“And where does Damien fit into all this, if I may ask?”

I shook my head. “I really have no idea. I’m still figuring it out.”

“You know he likes girls?”

“I said, I’m still figuring it out.”

“Fair enough.”

I paused, realizing what had just been said.

“Is it that obvious?” I asked Wes.

“Only to me,” he said.

It would take me another three months to understand why.

“Meanwhile,” he went on, “Sung and Frances.”

“Holy shit, right?”

“Yeah, holy shit. And you know the worst part?”

“I can’t imagine what’s worse than seeing it with my own eyes.”

“Gordon is totally in love with Frances.”

“No!”

“Yup. I wouldn’t miss practice tonight for all the money in the world.”

We all showed up. Mr. Phillips could sense there was some tension in the room, but he truly had no idea.

Frances was wearing Sung’s varsity jacket. And suddenly I didn’t mind it so much.

Gordon glared at Sung.

Sung glared at me.

I avoided Damien’s eyes.

When I looked at Wes, he made me feel like I might be worth saving.

Amazingly enough, during practice we were back in fighting form, as if nothing had happened. I felt like I could admit to myself how much I wanted to win. And not just that, how much I wanted our team to win. More for Wes and Frances and Gordon and Damien than anything else.

After we were done, Damien asked me if we could talk for a minute. Everyone else headed back to their rooms and we went down to the lobby. Other quiz bowl groups were swarming around; those that hadn’t made the semifinals were taking the night for what it was—a time when, for a brief pause in their high school lives, they were free from any pressure or care.

“I’m sorry,” Damien said to me. “I was completely off base.”

“It’s okay. I shouldn’t have been so mean to Sung and Frances. I should’ve just left.”

We sat there next to each other on a lime-green couch in a hotel lobby that meant nothing to us. He wouldn’t look at me. I wouldn’t look at him.

“I don’t know why I did that,” he said. “Reacted that way.”

It would take him another four months to figure it out. It would be a little too late, but he’d figure it out anyway.

We lost in the semifinals to Iowa. I knew from the look Sung gave me afterward that he would blame me for this loss for the rest of his life. Not because I missed the questions—and I did get two wrong. But for destroying his own invisible plans.

Looking back, I don’t think I’ve ever hated any piece of clothing as much as I hated Sung’s varsity jacket for those few weeks. You can’t hate something that much unless you hate yourself equally as much. Not in that kind of way.

It was, I guess, Wes who taught me that. Later, when we were back home and trying to articulate ourselves better, I’d ask him how he’d known so much more than I had.

“Because I read, stupid” would be his answer.

We lost in the semifinals, but the local paper took our picture anyway. Sung looks serious and aggrieved. Gordon looks awkward. Frances looks calm. Damien looks oblivious. And Wes and me?

We look like we’re in on our own joke.

In other words, happy.

TRACK TWO

Day 2934

When I am eight, Valentine’s Day is a Sunday. There is no certain minute I have to wake up, no bus to catch, no homework that needs to be handed in. Sleeping can blur itself into waking, and that is exactly what it does.

I wake up with my face against Yoda’s, my arm gently across Obi-Wan Kenobi. I take in the Star Wars sheets, the Star Wars blanket, the lightsaber lamp beside my bed. I have never seen any of the Star Wars movies, so this is all very strange to me. As I sit up in bed against a robot I will later learn to call a droid, I do my mental morning exercise, figuring out that my name is Jason today and that this is my bedroom. My mother’s room is on the other side of the wall; from the silence, I assume she’s still sleeping.

I know it’s Valentine’s Day because yesterday was the day before Valentine’s Day. I watched yesterday’s sister decorating her cards, putting extra glitter on the one belonging to her crush. She let me put stickers on the cards she cared less about, hearts I laid out in haphazard trails. I tried to imagine each kid opening his or her envelope, knowing full well I would be gone by the time they were delivered.

Now I get up and walk to the mirror. I don’t really pay attention to what I look like, but I do stare for a good long time at the pattern on my pajamas. If you’ve never seen Wookiees dancing before, it’s a very confusing sight.

On my desk, I find a dozen sealed white envelopes, each the size of a playing card. They are all addressed to MOM, the Os shaped into hearts.

It’s as if Jason has left me an assignment. I gather the stack in my hand and leave the room.

Holidays were important to me when I was young, because they were the only days almost everyone could agree upon. In school, there would always be a lead-up, the anticipation gathering into a frenzy as the day grew closer and closer. With Valentine’s Day, the world grew progressively red and pink as February began. It was a bright spot in a cold time, a holiday that didn’t ask much more of me than to eat candy and think about love.