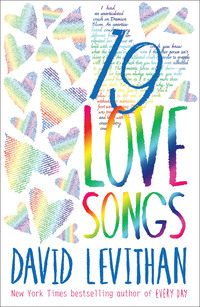

19 Love Songs

I knew another boy, Josh, probably wanted to ask her, too. But I figured, hey, I’d give Jordana the option and see what she wanted to do. We went on a nondate to Bennigan’s, and I stalled. I pondered. I worked myself up into an existential crisis while I ate mozzarella sticks and debated whether or not to ask her.

Which is when Roxette comes into the picture.

I almost didn’t ask Jordana to be my prom date. But then a Roxette song came wafting down from the Bennigan’s speakers, and it told me to listen to my heart. I figured this was a sign. My heart said go for it, so I did. I even told her I wouldn’t mind if she wanted to go with Josh. She said she wanted to go with me.

I was so relieved to have it over with.

I was, however, unprepared for the fact that I had just created more traumedy than I’d ever intended to create. By choosing a prom date, I was the one who stopped the music and sent all of my female friends flying toward the musical chairs. Many, it seemed, had thought it at least a possibility that I would ask them. I had, to put it indelicately, fucked everything up. Now the good girls had to grab hold of the nearest boys and hope it would work out. By and large, it didn’t work out well—even for me, since Jordana ended up wanting to go with Josh after all, causing awkwardness all around. Still, we look happy enough in the prom photos—the front row of good-girl friends, and then the back-row assortment of random boys tuxed up to squire them for the evening. All dressed up, we thought we looked so old. Now, of course, I look at the picture and see how young we actually were. We get younger every year.

Our friendships existed on the cusp of a different era; the way we communicated and what we knew were much closer to what our parents experienced in high school than what high schoolers now know. Within five years after we graduated, everything was different. We lived in a time when we had cords on our phones—if not connecting the handset to the base, then definitely connecting the base to the wall. We lived in a time when “chatting” was something that didn’t involve typing, and text and page were words that applied to books, not phones. If we wanted to see naked pictures, we had to sneak peeks in magazine stores, or rely upon drawings in The Joy of Sex, spreads in National Geographic, or carefully paused moments in R-rated videotapes. The only kids we knew in towns outside of our own were the ones we had gone to camp with. The only bands we knew were the ones played on the radio or on MTV. For me, it was a time before all the small pop-cultural things that might have tipped me off to my own identity before I hit college. Because I was happy, I didn’t really question who I was.

I don’t know whether the good girls were as ignorant as I was to my gayness, or if they figured it out before I did and waited for me to piece it together. One of them definitely got it—during my freshman year of college, Rebecca sent me a letter saying, basically, that it was totally cool if I was gay, and that I didn’t have to hide it anymore. I was hurt—not that she thought I was gay, but that she thought I was hiding something so big from my friends. I assured her that I would tell people if I were gay—and as of that writing, I was correct. Later on, in my own time, I’d figure it out. And as soon as I did, I didn’t really hide it. It seemed as natural as anything else, and I didn’t go through any of the anxiety, fear, or denial that I would have no doubt experienced had I figured it out in high school. It was a gradual realization that I was completely okay with, and everyone else was completely okay with. The good girls would have been much more shocked if I’d told them I was going premed.

Because I’ve grown up to have a writing life that brings me into contact with a lot of teens, I see all these possibilities open now that weren’t open then. I see all the fun trouble we could’ve gotten into. I see how late I bloomed into being gay. I see how being a good girl means missing out on some things, closing yourself off to certain experimentations and risks. It was a sheltered life, but I’m grateful I had the shelter. I needed the shelter. I bloomed late in some things, but I bloomed well in so many others. I know some good things I missed, but I also know a lot of bad things I missed, too.

Now most of the good girls—from high school, from college, from after—have found good guys or good girls to be with. And I have found the other boys who were once surrounded by good girls. Together we boys form our own good-girl circles, doing all the things we used to do exclusively with the good girls: confide, support, chatter, have fun. I don’t think many of us would have imagined in high school that we would one day have such circles, that we would one day find so many guys we liked, so many guys like us.

High school does seem a long way back now. But I will say this: I’m really glad I was raised by the good girls. I wouldn’t have become the guy I am without them.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов