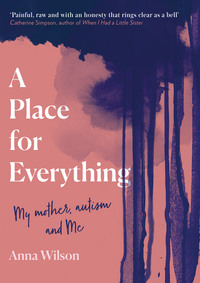

A Place for Everything

‘I’m concerned about Gillian,’ he says.

Not ‘my sister’. Not even ‘your mother’.

Cold fingers walk down my spine.

‘Her behaviour has become manic,’ he goes on. ‘I’m worried that your father is exhausted.’

Concerned.

Manic.

Worried.

Exhausted.

I know what this means. I have known for months, if I’m honest. Months during which I have done my best to listen and offer support to Mum. Months during which I have become frustrated with Dad’s refusal to discuss how bad things were getting. Months during which my frustration with both my parents has turned to anger and then panic, ending in me closing down, refusing further communication. This is why John is calling now – to force me back into the game.

I hold my breath and the edge of the kitchen sink.

Steady, now.

Steady.

‘I came back from France feeling that Gillian should go into respite,’ he is saying. ‘Your dad wouldn’t listen to me while I was with them, so I thought perhaps I should leave well alone. But Gemma’s just phoned.’ He pauses.

Gemma is my cousin, John’s daughter. A capable, logical, clear-thinking medic, just like her father.

I hear John sigh – a funny sound, as though he too is trying to keep it all together. ‘Gillian called Gemma first thing this morning to wish her a happy birthday,’ he says. ‘She apologised for missing it. Then she blurted out that the house was filthy. This set off a rant about having to clean the house all the time because it was too dirty. She added that she could see it was also falling apart.’ He pauses again.

Mum would be upset for having forgotten Gemma’s birthday, I think. But this isn’t the point he’s making. I don’t say anything. I wait for John to continue.

‘Gillian is convinced that there are huge cracks opening in the walls and ceiling of the house,’ John goes on. ‘She also told Gemma that she’s given herself third-degree burns while cleaning the oven with her bare hands, using caustic soda. This was why she’d missed her birthday – because she had to go to A&E.’

This is it. This is the bad news. He’s built up to it and he’s not going to stop now. I let out a sob; I can’t help it.

‘I’m sorry, Anna. She’s become dishevelled and unkempt and has developed a shuffling gait,’ John says.

Each word he utters is an exploding firework. Dishevelled. Unkempt. Shuffling. Dr John again: detached, professional, telling me what I need to know. I don’t want this diagnostic tone. I don’t want this detachment. Where has my Uncle John gone? Where are all the grown-ups?

Shuffling gait … What he really means is—

No. Can’t go there.

I’ve tried to push this out. I knew things were bad. I tried to say. So many times. The last time I saw Mum it was awful. She had looked ‘dishevelled and unkempt’ even then, if I am honest. I had taken the kids to London to meet up with my sister Carrie and her children. Mum had been on edge the whole time and had barely spoken to her grandchildren, whom she adores. She had obsessed over meal times and train times and wouldn’t come into the exhibition at the museum because the rooms were ‘too dark’. She had gulped the hot chocolate I had bought her and had scalded her mouth. Carrie had tried – I had tried – to talk to Dad, to say, ‘Look! Look at her!’ He had nodded and smiled and pushed our worries aside, and in the end we had done what we always do and taken his lead. Dad knows best. From then on we had decided to leave them to it.

‘She’s paranoid,’ John says.

And there we have it. I know he’s using the word in its medical sense, but I am the daughter of two classicists who always took pains to teach me the Greek and Latin source of words that we take for granted in English. I know where ‘paranoid’ comes from. Paranoia: from the Ancient Greek meaning ‘beyond the mind’. Panic. Pandemonium. Chaos. Paranoia. All from the Ancient Greeks. Didn’t they have a hell of a lot of good words for occasions such as this?

Because Mum is ‘beyond her mind’. Out of it.

Mad.

I stare at some water marks next to the kitchen taps. I try to focus, to hear what Dr John is advising.

Those water marks, though. Mum hates water marks. I fight the urge to grab a cloth and wipe the spots away.

Cracks in the wall. Caustic soda.

Water marks. Wipe them up! They’ll leave a stain!

John is still talking. He still sounds calm, but there is something off-key; a dislocation, a gap between the words he’s using and his measured, professional tone; she might be my mum, but she’s his sister too.

‘Your father is hiding his head in the sand, Anna. He is burying himself in an ever-expanding list of jobs that he feels need doing around the house – presumably to try to appease your mother. He is continuing with his canoeing and his singing, and he is ratcheting up their social life. These are distractions, but they are not working. Your mother is exhausted. She is entering a phase which I would say is borderline delusional. This isn’t depression, Anna,’ he says with emphasis. ‘She needs to go to hospital where she can be properly monitored and possibly even have electro-convulsive treatment.’

I hear myself whisper, ‘Electric shocks?’

‘It can be highly effective,’ John says.

I have seen the scenes played out in television dramas. Tied to a bed. Biting down on rubber. The sharp pain as a bolt of lightning surges through the body. I have read Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. I don’t want Mum to feel as though she’s been shaken ‘like the end of the world’. I don’t want her to see the air ‘crackling with blue light’, to feel ‘a great jolt drub through’ her till she thinks her bones might break.

What kind of a daughter am I?

How have I let my own mother get to this point?

What have I been thinking?

Back in February it felt as though I had to take a stand. It felt as though things had reached crisis-point – for me. I wrote to Dad and told him I couldn’t be involved any more, that Mum was sucking all the air out of me with her constant crying ‘Wolf’ – phoning me at all hours every day, sometimes multiple times a day, telling me how miserable she was, asking me to fix her, and then, when she didn’t like what I had to say – about her being depressed – turning the tables on me: telling me I was the one who was depressed. I told him I was having panic attacks and sleepless nights, worrying about Mum, but that everything I had tried to do to help was being ignored. And so I was cutting off contact for a while. To focus on me and my own family. To give myself space. For the sake of my own survival.

How self-centred and self-righteous my behaviour looks now. Now, I am so far away, so distanced, that when Mum really needs help (and Dad, poor Dad!), I am too removed to grasp how bad things have become.

Still, I can’t think of the right questions to ask. I am terrified in case John answers me with the very words I don’t want to hear.

He says them anyway.

‘I’m afraid you’re going to have to step in and take control. I’ve tried talking to your father, but he’s not listening.’ John pauses, then says it again: ‘You are going to have to step in.’

I want to say something sensible, to show that I understand, even though I don’t. Not really. Because I can’t. I can’t do this. Not me. This is my mum. She is the one who looks after me. I am the child here; don’t ask me. There must be someone else who can step in.

‘I’ve already tried to help!’ I say. I sound like an eight-year-old. ‘I’ve tried talking to Dad. I’ve suggested … everything! CBT, counselling, therapy. Yoga, even!’

And look how all that turned out. What was it she called it? ‘Namby-pamby nonsense’.

John’s voice takes on a quieter, warmer tone. ‘I know. I’m sorry.’ My uncle is back. He’s not going to let me off the hook, though. ‘Ring me if you need me. Let me know what happens.’

And that is that. End of conversation. No more discussion.

Over to me.

I put down the phone and feel the walls close in.

Three

‘There are several coping mechanisms [for a child whose parent is a person with AS]. [One] mechanism is to escape the situation … leaving home as soon as possible.’ 3

I am not ready for this.

I have my own life.

I have two children who are still at school.

One is doing her GCSEs soon, for goodness’ sake.

My husband works abroad.

I see him only at weekends.

I am trying to develop my career.

In between looking after the kids and running the house.

I can’t take on my mother as well.

I can’t.

I have my own life and I have fought hard for it.

I moved away from all this.

I don’t know how to cope with madness.

I feel as though I’m going mad myself.

I am not going back.

I am not.

I talk to myself as I pound the towpath.

I run and I run and I run.

I run down to the river.

May is the best month of the year to be here. And here is where I want to be, with the cow parsley and the kingcups and the herons and the moorhens and the ducklings and the cormorants and the kingfishers.

Not there. In my neat and tidy childhood home. With my mother.

Mum had been livid when we’d moved here.

‘What on earth are you moving to the bloody West Country for? It’s too far!’

Too far from her, was what she meant. But that was part of the allure by then. Not that we had a choice, as it was work that brought us here. But by 2007 I’d had enough of Mum demanding that I spend more time with her; complaining that I didn’t live down the road, near my mother, as she had done; ranting that I didn’t care about her feelings, that I seemed to care more about my friends than about her; that I was not a good daughter, that I should make more of an effort to let her see her grandchildren. Calling me every other day, sometimes twice a day, to catalogue my failings and list how I had let her down.

And now she really needs me. Now I can deny it no longer: this life was never really mine. What kind of a fool was I, thinking that I could move away, put some distance between us, save myself?

I can’t break the bonds that tie me to my mother. I can run and run as fast and as far as I like, but I will never escape.

Four

‘The real end, for most of us, would involve sedation, and being sectioned, and what happens next it’s better not to speculate.’ 4

I call Dad later that Sunday.

‘It’s fine, love. Things are fine. You shouldn’t worry.’ His voice is quiet and over-patient. Kind, as always. ‘Mum has hurt her hands, and been a bit pig-headed and stubborn, but otherwise everything is all right.’

I don’t believe him. I want to, but John’s words ricochet before my eyes. I am about to push Dad to tell me, honestly, how things are, when Mum gives me the answer. There is a clatter as she picks up the other phone. She breathes heavily into the receiver.

‘The house is disgusting,’ she blurts out. ‘And insanitary and probably unhygienic.’ Her voice is skittering, shaky, high-pitched.

Dad cuts across her, tries to mollify her. I listen to them talking to each other. They have forgotten about me. I am listening to two characters in a radio play.

These stereophonic conversations are not a new thing; Mum and Dad have been doing this for years, one answering the phone and the other picking up ‘on the other end’ to listen in. It always infuriated me, the way they ended up talking to one another, forgetting I was there.

Today is different. Today I am grateful for Dad’s stage management. I listen as he distracts Mum, moves her on from her cyclical rant about the state of the house, gently tells her that I have phoned for a chat.

Not forgotten then.

‘So, how are you, Mum?’ I ask.

Stupid question.

There is a brief pause, and then Mum turns on herself, attacking herself, reprimanding herself for being stupid. For having done nothing with her university degree (not true), for being useless.

‘Useless,’ she chants. ‘Useless, useless, useless, useless.’

Dad breaks in again. He soothes her with loving words. I can say nothing. I’m the one who is useless.

Mum goes quiet for a while. As Dad talks I’m reminded with a stab of panic of a friend of mine who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. I went to visit her when she was being treated in a mental health unit during a frightening psychotic episode. She told me repeatedly, at high speed, how useless she was and how she could no longer study, how she would never get her degree, how the words were nonsense on the page; black, jumpy shapes that held no meaning.

‘Mum’s gone,’ Dad says, breaking into my thoughts.

For a second I misunderstand. Yes, she’s gone all right.

I take a breath. Now’s my chance. I have to make Dad see. Things can’t go on like this.

‘I don’t know how to say this, Dad, but the way Mum’s talking reminds me of F when she was sectioned.’ I’m referring to the friend I have just been thinking about; Dad knows it.

‘Oh God,’ he whispers.

All forced jollity gone. All pretence abandoned.

I hear heavy breathing coming down the line.

‘Dad?’

‘Oh shit and fuck, she’s picked up the other phone again!’ There is a clatter and I can hear Dad shouting, ‘Gillian!’ The swearing and the anger in his voice shake me. He never used to swear or shout. Even if I had wanted to be reassured by Dad’s patient voice earlier, I can’t ignore the facts now.

I hear hectic sounds, of Dad chasing Mum around the house, shouting then soothing and cajoling, trying to get the phone off her so that he and I can talk in private. He finally succeeds in grabbing it from her, then tells me – spitting the words at me – that he is spending too much money, that he is booking things to do, to take Mum out to ‘distract her’ and then she is insisting he cancel them.

‘She doesn’t want to go out, but she doesn’t want to stay in either!’ he cries.

The sudden change from soothing, comforting Dad to frightened, confused husband is too awful. I should pack a bag and go to him, right now. He has reached his limits. No more smiling and nodding. Everything is clearly not ‘fine’ any more.

Why don’t I put down the phone and go?

I know that things are serious. John’s right. It’s not depression; it’s more than that.

Yet, still, I don’t go, because I’m not ready; I don’t think I ever will be.

Five

‘Myles and Southwick … described a Rage Cycle for adults and children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) which includes high functioning autism. They describe what happens when the person with ASD fails to recognise or is unable or unwilling to prevent their build-up of anger. This Cycle of Rage has three parts: rumbling, rage and recovery.’ 5

Mum is gripping me around the wrists, shaking me. Her fingers are tight on my skin, like hot wires. Her eyes flash emerald poison; her teeth are bared like a wild dog.

It’s 3.15 a.m., the next morning. I wake, gasping. Mum’s face is burnt on to my retina: her teeth clenched, her face taut with fury. Her face as it used to be so often when I was younger. The familiar old questions nagging at me: What have I done? Or not done? How have I made her so cross?

Memories of the day before rush in. The phone call, the discussions with my husband and sister. The rising panic. The fear. I feel as though someone is standing on my chest.

I can’t go back. I can’t step in. Mum hasn’t done anything violent for years, but memories of her past rages rush towards me every night now. Why? Why, when she is so meek and mild and frightened, when she needs love and understanding, why am I being reminded now of those darker times? They have haunted me recently: her anger at me being late, at making a mess, at ‘answering back’. Her fury that often seemed well out of proportion to the sin at which it was directed, and yet felt, to a smaller, younger me, justly deserved. It was the look on her face that always frightened me more than anything. Those eyes; wild, glistening. Those teeth. The rage that used to come from her was worse than anything else she could throw at me. Yes, she sometimes hit us, but I knew so many children whose parents slapped them. It was the Seventies – no one thought to question physical punishment. The thing I feared most was the shaking. The last time she shook me I was no longer a child. I had children of my own. She had taken hold of my wrists and shaken me, spitting fury into my face, her expression as it had been so often in my childhood: stretched, red, out of control. And grown woman that I was, I had been terrified. I realise now that it wasn’t actually violence or anger that I was frightened of. It was hatred. That was the look I saw on Mum’s face. And that was the most unbearable thing – that my own mother could hate me, no matter how hard I tried to be a good girl.

It’s getting to the stage that I’m dreading sleep. I don’t know why I’m having these dreams when my mother is now incapable of any emotion other than fear. But then fear is what has always been at the root of all her behaviour. Anger was a defence mechanism. Now that all her defences have evaporated, the fear is exposed. And it is contagious.

Later that morning – Monday 13 May 2013 – I call Dad to try one last time to persuade him to take Mum to hospital as John suggested.

‘John thinks that she really needs a rest.’ I am aware that the time for such euphemisms is gone, but I also know that I haven’t the strength to use raw, terrifying words such as ‘mental health unit’ or ‘psychosis’ – or to mention sectioning again.

There is a pause on the other end. I assume Dad is preparing himself to tell me, yet again, that I shouldn’t worry and that ‘everything is fine’. The silence lengthens.

‘Would you like me to come and stay?’ I ask, my voice high, overly patient, as though speaking to a young child.

Still I get no response.

Then he howls.

A huge, keening, animal howl from somewhere deep inside him.

It rips right through me. My hands start to shake. I stagger and thrust the phone at my husband so that he can hear.

‘Go. Go now,’ he tells me.

Six

‘I understand that my autism makes me a difficult person to deal with: I don’t know when to back off.’ 6

The drive from Wiltshire to Kent passes in a blur. At one point I realise I’m holding my breath, which is what Mum does when she’s frightened. I force myself to breathe in slowly, deeply, to breathe out to a count of three. It doesn’t work. I gulp and snatch at the air. I’m going to have a panic attack like the one I had in February when I was driving to see a friend. I drove the wrong way down a one-way street and arrived at my friend’s gasping and sobbing. I turn on the radio, find some soothing music. I pull myself together, count down the motorway exits.

This leg of the journey is so familiar. In the past, on my visits back home after leaving it for the first time, this length of the A21 was where I would feel a warm rush of nostalgia. There is a bridge that crosses the A road shortly after you leave the M25. It is an arc of concrete – hardly a thing of beauty – but to me it has always said ‘home’. As I passed beneath it I would exhale the word, feel my shoulders go down, knowing that I was going back to where I belonged. Shortly after passing under this bridge, the Weald of Kent is laid out beneath you. A bowl of green and pleasant land which, in my childhood, was full of orchards, oast houses, farms and weather-boarded cottages. It represented to me the ideal of what home was: calm and comforting and familiar. Like Mum on her best days.

Because Mum could be everything you ever wanted in a mother. She could cuddle you and stand up for you and help you with your homework and make cakes for you and cook delicious meals from scratch and sing along to your favourite songs in the car and smile when you picked her a bunch of daffodils. She could be the most beautiful mum at the school gate in her lovely dresses with her soft, fluffy dark hair combed into pretty styles. She could look at your drawings and your stories and smile and say she was proud of you. She could sit and listen to you play the piano and tell you how clever you were.

She could keep the house neat and tidy too, hoovering and dusting on the same day each week, changing the sheets and towels on the same day each week, polishing the parquet floor on her hands and knees on the same day once a month, ironing everything that could be ironed into crisp piles.

She was there for us, all the time. Even when she had a teaching job, she made sure that her hours fitted around us. She took us to school, she fetched us from school, she mended our clothes, she polished our shoes. She was constant and solid and she made us feel safe.

Most of the time.

Dad commuted to London. Unless he was travelling for work, he would come home at the same time every evening. When we were small he would make it back in time to read bedtime stories. As we got older and stayed up later we would wait to eat our evening meal with him. When I visited as a young adult, the sound of his key in the lock still had me running to give him a hug.

Everything had a rhythm to it. As long as you didn’t make Mum angry, as long as there were no unwelcome surprises, as long as you were good, then everything was ordered and quiet, comforting and safe.

When I was living in student accommodation or a dingy flat, going home to Kent was a welcome break. I knew I would be greeted with hugs and lovely food and fresh, clean linen. I looked forward to going back.

So when did I start to dread this journey? When did the sign for the A21 make me wish I hadn’t agreed to come? Was it when I got engaged? Was it the leaving and cleaving that did it? Or was it when I ventured into motherhood and dared to go back to work when my daughter was six months old? Whenever it was, David became used to the way I would start to jitter as we approached the turn-off. My right leg would start to jiggle up and down. I would check my watch over and over to make sure we weren’t going to be late, the cardinal sin that could wreck a visit before it had even begun.

It’s hard to know when any relationship veers off course. What had become increasingly clear over the years between my marriage in the mid-Nineties, and now in 2013, was that Mum did not deal well with me and my sister growing up – and away from her.

Arguments started around the planning of my wedding. I had always been a pretty compliant child and teen, but suddenly I had strong opinions that I wasn’t about to compromise. I didn’t want to have the service in the same church that Mum and Dad had got married in. It was too big and didn’t feel right for me and David. Then I ‘insisted’ on living in London rather than moving back to Kent. The fact that work kept us both in the capital was not a good enough reason – Dad worked in London, but he commuted from Kent. Why couldn’t we do the same? Once grandchildren came on the scene, my geographical distance made things so much worse for Mum. No matter that I called and visited regularly. No matter that Mum saw my daughter once a week when I went back to work. Nothing was enough because I had not followed the pattern preordained for me by Mum.