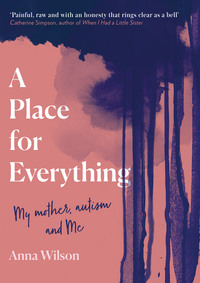

A Place for Everything

The clashes escalated over the years. We still saw one another and spoke regularly on the phone. But when my grandmother died, I felt that Mum’s dependency on me grew and grew until it became suffocating; I hadn’t realised how much of a buffer Grandma was until she was gone.

Grandma died on 26 September 2008. Mum’s mental health started to decline after this, but because it manifested in a series of worries about her physical health, nothing was put in place to help. Looking back in her medical notes now, I see that at various points health professionals had observed ‘heightened levels of anxiety’ and that Mum was assured that her physical complaints were not as serious as she believed them to be. And yet, apart from a seemingly rogue prescription for Prozac at one point around the time her father died, and some Valium to calm her the night before my wedding, nothing else was done to help.

By 2012 Mum had undergone surgery for uterine prolapse – something she had been advised against as she was becoming increasingly anxious and the consultant feared that the operation would be too much for her mental state. He was reluctant to operate, but Mum insisted. Sleeplessness was also becoming a huge problem for her, and she was calling me and Carrie daily, if not multiple times a day, to tell us that she couldn’t sleep, was ‘on edge’ and didn’t know what to do. It was at this point that Carrie and I were reading up obsessively in a bid to find a magic cure for Mum. We were convinced that Mum’s insistence on her body ‘falling apart’ was an outward manifestation of the state of her mind. We looked up and sent her advice on the benefits of the CBT the GP wanted her to try. We sent her links and articles on aromatherapy, yoga, meditation apps, even Epsom salt baths. We both regularly sent her gifts of things we hoped might help; we met up with her, organising outings, following the example of our grandmother whose first response with Mum was always to take her out ‘for a treat’ or buy her something ‘to cheer her up’.

By the end of 2012, Mum was seeing a psychiatrist privately. She had been to her GP on many occasions about her sleeplessness and had quickly given up on the CBT that had been recommended. Both Carrie and I were sceptical that anything was being achieved by the psychiatric appointments. The consultant had diagnosed depression and had started Mum on a series of drugs. When these had no effect on Mum’s insomnia, he had told her, according to Mum, that she would ‘probably always be miserable’ and that there wasn’t really much more he could do.

Mum relayed this conversation to me in February 2013. I will never forget it because it was half-term and I had taken the kids to London. I remember it was evening – dark and cold. I was walking across Brook Green in Hammersmith to pick my daughter up from a sleepover with a friend I had never met. Mum had already called me twice that day. I nearly didn’t answer because by then the very sight of the word ‘Mum’ on the screen was enough to send me into a panic, and I didn’t want to arrive at Lucy’s friend’s house in a state. However, I also knew that Mum would ring and ring if I didn’t pick up. I continued walking as I answered.

‘Hi, Mum? I can’t talk now. I’m on my way to get Lucy.’

Mum answered with the sort of half-snort she gave when she wanted to convey maximum disapproval. ‘I don’t know why you couldn’t come to us for half-term. I wanted to tell you: the psychiatrist says I will probably always be miserable. I don’t know why you think I need to see this man anyway,’ she added. ‘It’s a waste of money. There’s nothing wrong with my mind – it’s my body that’s the problem. And I can’t sleep. The psychiatrist says you and Carrie should be kinder to me and then I’ll be fine.’

I remember stopping, the cold air catching in my throat. Kinder to her? Kinder? It was like a slap. Or a shake. I ended the call hastily and pulled myself together so that I could be the mum I needed to be for my daughter.

The next morning Mum called again. She said the same things and berated me for not helping her. I remember I was with both my children and my mother-in-law was there. I remember hurling my phone down and bursting into sobs. I remember my mother-in-law looking horrified before putting her arms around me. I remember saying, ‘She won’t leave me alone!’ I remember feeling guilt and shame at the way I was talking about my mother to my mother-in-law. I remember feeling utter, utter despair.

It was shortly after that that I had a panic attack and wrote to Dad and said I couldn’t cope any more. I needed to cut off contact for a while.

I have passed that beautiful view of the Weald now. I have passed the village where my loving, gentle grandmother lived, where I would stop off on my way to seeing Mum and Dad. I have driven past the little church where David and I were married, in spite of Mum’s protests. I have driven past my little primary school where I made my first relationships outside the family. I am approaching the house now. What on earth will I find when I get there? It’s been over three months since I’ve been there, and after that phone call with Dad, I’m dreading what lies in wait.

Seven

‘The child of a parent [with ASD] learns not to express emotions such as distress.’ 7

I don’t know what I imagined I would find when I arrived, but it wasn’t this. I pull in to the drive to see there are workmen painting the white weatherboard. A swarm of them, crawling over the flat roof above the study, scaling the walls outside the sitting room, brandishing paintbrushes, like the playing cards in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Maybe I am the one who’s become delusional. Am I seeing things? Am I making this up? Mum is out of her mind, Dad is howling down the phone – and there are workmen painting the house as though it’s just a normal Monday morning.

I get out of the car to see my mother’s face peering at me through the glass in the front door. Small, wide-eyed, white-haired and frightened. Not the upright, well-dressed, fiery-tempered woman of only a year ago. Not the mother who would bark, ‘You’re late!’ even when I had phoned in advance to let her know I was stuck in traffic.

She opens the door a crack.

‘Dad’s out,’ she says, her voice high and quavering.

‘Where’s he gone?’ He can’t have left her alone, surely?

‘He’s gone to do some shopping. We’ve got no food.’ She is speaking too fast. ‘The fridge is making a funny noise.’ She gives a funny little gasp. Her hands are shaking.

I push the door open, put my bags down, take her into my arms. I hold her and kiss her head while she asks, ‘Why did you come? I didn’t want you to come. The walls are cracking up.’

I let her go and point to my bags. ‘Dad didn’t need to go out. I’ve brought lunch. And some flowers.’ I sound like a nursery school teacher mollifying a crying child.

‘I don’t want flowers. I can’t eat that food. I can’t eat a thing,’ she says. ‘I’m losing weight. Look.’ She grabs the waistband of her trousers and pulls it away.

It is alarmingly loose. She says she’s lost half a stone. Looks more like a whole one to me. Mum has struggled with her weight since the menopause. She always wanted to lose that tricky last half stone. But not like this. Not like this.

She begins to pace up and down, wringing her hands and moaning.

‘The house is in a state. Look at it! I’m in a state. I’m useless, useless, useless.’

She is a textbook picture of a madwoman. Unkempt, as John said, her hair sticking up on end, her eyes staring, she is constantly on the move, talking in a loop, moaning, gasping and whooping. Stick her in a long white nightie and dim the lights and she could be a nineteenth-century loony, straight out of the asylum.

Her ranting goes up a notch as she paces. Her sentences are short and breathlessly sharp. My heart begins to race in time with her galloping words.

‘I know what the problem is. It’s the house …

‘… I have let it get out of control …

‘… Everything’s cracking up!

‘Look at the weeds!

‘Look at that bush!

‘We’ve had decorators in and they’ve left dust everywhere …

‘… We’ve got nothing to eat. There’s no food in the house.

‘You shouldn’t have come …

‘… What am I going to wear? I’ve got no clothes …

‘… I have to do some washing …

‘… I have to do the ironing …

‘I need to get my hair done!

‘Look at the state of everything …

‘There’s nothing wrong with me. I know what the problem is. It’s the house.’

She is a river in spate; her words rushing, gushing, teeming, spilling over the banks and flooding the air around her. The word ‘house’ has acted like a trigger for her to list everything that is ‘cracking up’ or ‘falling down’ or ‘getting out of control’. This panicky tour of the house and garden is punctuated by alarming exclamations about how she’s ‘tried and tried’ and how she has ‘behaved very badly’, and she is ‘useless’, can’t I see?

I occasionally manage to distract her for a few moments by asking her to sit and hold my hand. I tell her random, disjointed anecdotes about her grandchildren.

Within seconds she is up, pacing again, and the talking resumes. Round and round and round. On a loop. Loopy.

Dad comes home and quietly goes about unpacking shopping, barely acknowledging my presence.

I follow him into the kitchen, Mum hot on my heels. ‘What are those men doing, Dad?’

‘They’re painting the drainpipes and fixing things up a bit,’ Dad says calmly. ‘Would you like a coffee?’

Fixing things up a bit? Papering over the cracks. Fiddling while Rome burns. It’s what we’ve all been doing for years.

Mum comes up behind me.

‘Listen to the fridge,’ she insists.

I listen.

‘I can’t hear anything,’ I say.

‘It’s not working,’ Mum says, opening and closing the door.

‘I mean – I can hear the normal noise a fridge makes,’ I say hastily, trying to reassure her. ‘And everything seems cold enough to me—’

‘Why did you come? We haven’t got any food. I didn’t want you to come.’

Didn’t want me to come?

She doesn’t want me to be here? Seriously?

After years of begging me to come. To see her, to sit with her, to ‘just talk’ to her, to move back to Kent, to be there, just be there, be there for her, to not spend all my ‘bloody time in the bloody West Country’? Now, when she’s – what? Ill? Manic? Insane? – she doesn’t want me? WHAT AM I SUPPOSED TO DO?

Dad keeps his head down. He doesn’t look me in the eye.

I bite back frustration and fill the air with empty words instead. Witterings about the journey, about the work Dad’s suddenly decided to do on the house, about the coffee. Dad joins in gratefully. Move along now, nothing to look at here.

I go to the loo, and after I have washed my hands I glance in the mirror and see that I look as ‘unkempt’ as Mum. Unwashed hair, scraped back because I had been about to go for a run when I called earlier. No make-up. Wild and wide-eyed and frightened. Mad as a hatter.

I shiver. The house is freezing. It’s grey outside, yes, but it’s May. I shouldn’t be shivering. I realise I haven’t brought a change of clothes, a jumper or a coat. I rushed out too fast. I go and take a sleeveless Puffa of Dad’s from the coat stand in the hall.

Dad has gone back into his study. I know he’s hiding, that he needs a break. But I need him. I need him to tell me what to do, to take the lead. To be Dad. To step in. For once.

I hover in the doorway. ‘Have you taken Mum to the doctor?’

‘We’re still seeing the psychiatrist,’ he says carefully. He doesn’t look up from his computer screen. The implication is, ‘case dismissed’.

He knows I’m not buying it, though – that this is not the answer I’m looking for. He knows that this psychiatrist is next to useless as far as Mum’s condition is concerned, that nothing has improved while she’s been under his care. That everything has got immeasurably worse. And now this man is still taking my parents’ money, still pacifying Mum with platitudes and pills, and still not putting in place any continuity of care for Mum at home.

I think about all these things as I stand in the door to my father’s study while my mother runs through the house pointing out cracks in the wall and calling out in a high-pitched wail.

I think about everything that has led to me being here and I feel my fury rise up against this psychiatrist. Where is he now that Mum has lost her grip on reality? How can he say that a holiday in France and a bit of kindness will stop Mum’s delusions? I would like to get hold of him and force march him round here and show him what his empty words and pills doled out like sweets have done.

But I mustn’t take it out on Dad. I must breathe and stay calm and breathe and stay calm and breathe …

Dad is still typing at his computer and ignoring me.

‘Dad.’ I take a careful step towards him. ‘I don’t think this particular psychiatrist is getting to the bottom of things. I think Mum needs to be referred by the GP to an NHS psychiatrist so that she can have proper joined-up care. John thinks—’

‘I’m sick of hearing what everyone thinks!’ Dad snaps. He whips round in his chair to face me, his expression such a Molotov cocktail of anger and fear that I run from the room.

Dad never gets angry, Not with me, not with Mum, not with anyone. And yet today he has sworn down the phone, howled and now shouted at me. What is happening?

I retreat to my old bedroom, the place I always went to when things kicked off. My old bedroom, which has not felt like mine for over twenty years. I fling myself onto the bed. I wish I could scream and shout like Dad. I want to pound my fists against something. Break something. Preferably the psychiatrist. Instead I bite it all back. Like I did when I was a child and Mum had ‘had enough’ of me and Carrie and had gone to shake her fists in the mirror and yell.

I am still a child. Their child. But even as I think that, I know that the time has come for me to be the parent.

Eight

‘I hated having showers as a child and preferred baths. The sensation of water splashing my face was unbearable.’ 8

I sit and stroke Mum’s hair.

‘I want my mum!’ she wails.

So do I.

I want my grandmother. The woman who mothered me when Mum could not. The large, cuddly, soft, smiling grandma who sat me on her lap and sang to me; who let me play with her precious Singer sewing machine; who taught me how to make pastry and didn’t mind when I made a mess; who had me and my sister to stay when things got ‘too much’ for Mum; who tucked us in at night and kissed us three times, saying, ‘Een, tween, toi – that’s French, that is,’ with a twinkle in her eye.

But Grandma is long gone; her ashes cast under a forgotten tree by the river. She is dead. And with her passing, any real understanding of how to cope with this woman, her daughter, my real mother, has also died.

I try to persuade Mum to rest. She shouts back, ‘No! I need to wash my hair. It’s disgusting.’

It’s a relief to have her talk about something new, even if I immediately recognise the signs of a new obsession. At least she’s not talking about the house falling down or the lack of food. I say I will wash it for her.

‘You can’t,’ she snaps.

‘Mum, I can. You have burnt your hand with caustic soda. It’s bandaged. You are not allowed to get it wet.’ I’m being bossy. A bossy mother to my child-parent.

Mum jumps up from her chair, whooping and moaning, and begins the incessant walking in circles again, repeating that she needs to wash her hair. To do it herself, like the Little Red Hen.

I manage to lead her upstairs to the bathroom, talking calmly. (I hope I sound calm; I don’t feel it.) I run water into the basin while I keep talking. I go over to the bathroom cabinet to fetch shampoo.

Mum watches me. ‘I want you to use the red cup.’

‘I know.’

‘Not the shower.’

‘I know.’

‘The red cup. Up there.’

‘Yes.’

‘And don’t drip water everywhere.’

‘I won’t.’

Mum has always hated marks, smudges, mess, things in the wrong place. Things not done her way. She does everything the way she always has. Washing her hair in the basin, not the shower. Using the red cup. Always the red cup. Only the red cup. She is attached to this red beaker, which we used to take on picnics. I remember the warm orange squash that was poured into it. It always made me gag, but I drank it anyway. Gagging for a few seconds was better than making Mum upset. I have always disliked orange squash. I have always hated washing my hair over a basin.

Nothing really changes. Even in her madness, Mum is not changed; she is just Mum with the volume turned up.

When we were children Mum used to wash our hair over the basin on the same day at the same time every week – no more and no less frequently. She would scrub our scalps hard, scratching at them with her fingernails. It was a brisk, rough affair. I quite liked the massage. I didn’t like the shampoo trickling into my eyes, making me squirm. Mum didn’t like it when as teenagers Carrie and I insisted on changing from baths and weekly hair washes to daily showers and washing (and dyeing) our own hair.

I look for the red cup in the bathroom cabinet. I keep talking to Mum, making sure my voice is even and calm. I don’t know what I’m talking about. It doesn’t matter so long as I can prevent her from leaving the room. I need to keep her away from Dad, who is in his study, pretending to do something on the computer. Taking a break. I can’t allow Mum to upset him again. I can’t have two crazy old people on my hands.

Bathrooms invite crises. I think of Carrie and hair-dyeing escapades gone badly wrong – her begging me to touch up her Monroe roots with peroxide that had already burnt her scalp, me wincing as I applied the bleach, trying to avoid the scabs on her skin. I remember, too, screaming arguments ending in running to this room. It was the only one in the house with a lock on the door.

I remember the evening before my wedding, locking myself in here with Carrie.

I was staying here in Kent while David spent the night in London with his best man and the friends who were going to be his ushers. Mum had planned a big family get-together: uncles and aunts and cousins from both sides of the family. I didn’t question whether this was what I wanted; at every stage of planning this wedding Mum had made it clear that it was she, not I, who was in charge. She was giving away her eldest daughter and she was going to do it the way tradition demanded. And tradition demanded that the bride did not see her groom the night before the wedding. So I was given a bed in my old bedroom, already stripped of anything that reminded me of childhood, and the whole family was invited round. And that was that – no arguments.

I knew Mum was on edge – she was jittery and irascible, which were warning signs that I needed to keep my head down. I didn’t pay her too much attention, though. Why would I? I was too excited, too fixed on the next day and the rest of my life to come. It was only after the wedding that someone – Carrie, I think – told me that Mum was on Valium and that Grandma and Dad had had to keep her calm before I arrived. It was years later that I found out that the build-up to the wedding had made Mum so distraught that she had convinced herself that she had serious gastro-intestinal problems and had had a colonoscopy, which proved negative. Yet another occasion on which her levels of anxiety had not been considered to be the real medical problem.

I knew enough that night to instinctively keep my own nerves to myself. I knew I didn’t want an explosion the night before my wedding. So when I got my cheap hairbrush tangled fast in my hair while blow-drying it, I certainly wasn’t going to call for Mum. I called down the stairs to Carrie instead, keeping my voice careless and calm, asking if she could come to me. I had to keep any hint of panic from my tone, or Mum might have rushed in. She might have screamed and shouted. She might have even tried to rip the brush from my head, or cut off my hair in chunks.

Carrie came, clocked the situation immediately, whispering that it would be fine. She gently locked the door before carefully teasing the hairbrush free. It took well over an hour. Mum shouted up to us more than once, wanting to know what we were ‘up to’. We never told her what had happened.

I test the water for Mum now. The basin is full. The water is warm. I feel a surge of longing – to plunge my own head into it, to breathe in the water, to give myself to it, to be submerged, to stop the hammering in my chest, the whirring in my brain.

Instead I fetch a towel to put over Mum’s shoulders. I ask her to bend over the basin and close her eyes, explaining what I am going to do.

She becomes meek, doing as I ask, dipping her head forward. I scoop some water into the red cup and then empty it over Mum’s hair. A baptism. A cleansing. Her white roots flatten and the skin of her scalp is revealed. It is so pale, so pink, so pure. Baby-soft.

‘Is that OK?’ I ask.

‘Hmmm.’ Mum sounds content.

I look at Mum’s fragile scalp and listen to the quiet trickle of the water running off her. The last time I did this was for my children, a good five years ago, when they too refused to use the shower. I would tip them back in the bath, holding their little bodies in the crook of my elbow, cradling their heads to make sure they didn’t fall or get shampoo in their eyes. Then I would gently massage their soft pink scalps as they smiled up at me. It was always a pleasure, washing their hair. They would giggle and gasp when I poured the water using their own plastic cup.

Mum’s head blurs under my massaging fingers. Mothering Mother.

I want my mum.

Nine

‘Some adults report being “blinded by brightness” and avoid intense levels of illumination … There can also be an intense fascination with visual detail, noticing specks on a carpet.’ 9

I’m in a dark house with my son. We have been travelling all day and this is the only place we could find to stay the night. Now we can’t find the way to our room. The light is fading rapidly and I can’t see any light switches. Tom is holding on to me as I feel my way along the walls. Entrances open before us, then close as soon as we approach. Tom is chattering to me as he did when he was nine; telling me about bats and how many species there are in the UK. I am groping into narrower, darker corridors, my right hand before me, doing the best I can not to scream and frighten my son. I touch the walls again and feel that the wallpaper is moving. It bulges and writhes with living things. I grip Tom’s hand tighter and we run. We find our room. It is wallpapered all over, from the floor beneath our feet to the ceiling above. Even the basin in the bathroom is wallpapered, as though wrapped up for Christmas.

I wake. The nightmare is still in the room with me. I can’t shake it off. It brings back memories of a book I read years ago – a short story, called The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. I used to be morbidly fascinated by this story of a woman’s descent into madness. She obsessed over patterns in the wallpaper in her room, believing them to be alive. At the time, I didn’t think of the book’s portrayal of insanity as anything other than fiction. Until now.