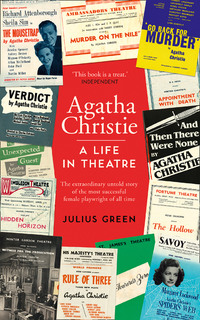

Agatha Christie: A Life in Theatre

There is no reference to Someone at the Window in Christie’s autobiography, in her correspondence or in the licensing records of Hughes Massie, although her notebooks do contain some work in progress. The final script appears to be ‘performance ready’, but was never submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s office, and neither does there appear to be any record of it having been tried out by one of the club theatres, where the audience had to sign up as members and which therefore did not require a licence. Unlike other unperformed work of hers, she appears not to have returned to it, reworked it or lobbied for its production. She perhaps appreciated that its dramatic construction rendered it unattractively cumbersome as a production proposition. With its loss, sadly, we have in my opinion been deprived of some of her best dialogue for the stage.

One work which Christie did return to was the similarly lengthy Akhnaton, her remarkable historical drama about the idealistic pharaoh, father of Tutankhamun. Akhnaton, who dreams of ‘a kingdom where people dwell in peace and brotherhood’ and spends much of his time composing poetry, attempts to promote a pacifist philosophy and to unite the polytheist Egyptians under one god; policies which inevitably do not go down well with either the army or the priesthood. The action of the play takes place over seventeen years, moving from Thebes to Akhnaton’s purpose-built Utopia, the City of the Horizon, and involves a cast of twenty-two named roles, including an Ethiopian dwarf, not to mention scribes, soldiers and other extras, as well as a spectacular parade featuring ‘wild animals in cages’ and ‘beautiful nearly nude girls’.

Christie commentators tend to be united in their praise for the piece; including even biographer Laura Thompson, who is generally dismissive of her work for the theatre. In the absence of a response from critics, Charles Osborne sums it up well: ‘Akhnaton is, in fact, a fascinating play. It deals in a complex way with a number of issues: with the difference between superstition and reverence; the danger of rash iconoclasm, the value of the arts, the nature of love, the conflicts set up by the concept of loyalty, and the tragedy apparently inherent in the inevitability of change. Yet Akhnaton is no didactic tract, but a drama of ruthless logic and theatrical power, its characters sharply delineated, its arguments humanized and convincingly set forth.’30

The play, eventually published in 1973 and not performed in Agatha’s lifetime, is usually dated as having been written in 1937. The earliest surviving copy is clearly stamped by the Marshall’s typing agency as having been completed on 12 August of that year, and the ancient Egyptian subject matter certainly makes sense in the context of her involvement with the archaeological community since her marriage to Max Mallowan. In introductory material written for its publication, Christie refers to the date of its writing as 1937,31 although thirty-six years later she may well simply have been using the date on the typescript’s cover as an aide memoire.

Mallowan himself touches briefly but perceptively on a small number of Agatha’s plays in a chapter towards the end of his autobiographical Mallowan’s Memoirs, published in 1977, a year after her death. Akhnaton, he says, is

Agatha’s most beautiful and profound play … brilliant in its delineation of character, tense with drama … The play moves around the person of the idealist king, a religious fanatic, obsessed with the love of truth and beauty, hopelessly impractical, doomed to suffering and martyrdom, but intense in faith and never disillusioned in spite of the shattering of all his dreams … In no other play by Agatha has there been, in my opinion, so sharp a delineation of the characters; every one of whom is portrayed in depth and set off as a foil, one against the other … the characters themselves are here submitted to exceptionally penetrating analytical treatment, because they are not merely subservient to the denouement of a murder plot, but each one is a prime agent in the development of a real historical drama.32

Mallowan appreciates the play’s classical dramatic construction – ‘the play moves to its finale like an Aeschylean drama’ and, like other commentators on the piece, notes its contemporary relevance: ‘Egypt between 1375 and 1358 BC is but a reflection of the world today, a recurrent and eternal tragedy’. He does, however, appreciate why theatrical producers might hesitate. ‘Good judges of the theatre have deemed it beautiful, but would-be promoters are daunted by the frightening thought of an expensive setting and a large cast.’

Max introduced Agatha to Howard Carter at Luxor in 1931, describing the man who discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 as ‘a sardonic and entertaining character with whom we used to play bridge at the Winter Palace hotel’, and also to his friend Stephen Glanville, another leading Egyptologist who later became Provost of King’s College Cambridge and who Max claims offered Agatha guidance relating to source material for her historical drama. However, although Agatha’s new-found archaeological connections were understandably instrumental in the realisation of the script for Akhnaton that we now know, there are some ambiguities about the play’s inception that indicate that it may have had an earlier existence. In her autobiography, Agatha credits Glanville at some length for his assistance with the 1944 novel Death Comes as the End, which is set in ancient Egypt, but not with having helped her with Akhnaton. This may, of course, simply be because the play had not been published when she finished writing her autobiography, and she did not want to confuse readers with detail about its creation. She refers to it only twice, on the first occasion noting that ‘I also wrote a historical play about Akhnaton. I liked it enormously. John Gielgud was later kind enough to write to me. He said it had interesting points, but was far too expensive to produce and had not enough humour. I had not connected humour with Akhnaton, but I saw that I was wrong. Egypt was just as full of humour as anywhere else – so was life at any time or place – and tragedy had its humour too.’33

Despite the notoriously inaccurate chronology of Agatha’s autobiography, not least when it comes to her plays, one thing it tends to be very clear on is which part of her life she spent with Archie and which with Max. Her first mention of Akhnaton occurs very much in the former section of the book, in a sequence where she is recounting her activities after returning from the Grand Tour in 1922 and before her divorce. Immediately before this she mentions ‘the play about incest’ (i.e. The Lie) and there is no link with her second husband or his archaeological interests. To me, this indicates that she is placing the origins of Akhnaton in the pre-Max era of the mid-1920s. Agatha was of course no stranger to Egypt prior to meeting Max and his friends, having spent some time in Cairo with her mother as a seventeen-year-old, although one suspects that she was more interested in potential suitors than mummified Pharoahs during this particular visit. She notes that Gielgud wrote to her ‘later’, and this handwritten letter, dated simply ‘Friday evening’, was doubtless in response to the version of the script that was typed up in 1937 and which may well by then have benefited from Stephen Glanville’s input; Gielgud writes from an address in St John’s Wood which he occupied between 1935 and 1938. Gielgud felt that Akhnaton requires ‘a terrific production in a big theatre with a great deal of pageantry. Personally I think it would have a great deal better chance of success if it was simplified and so made possible to do in a smaller way.’34

Agatha was a great admirer of Gielgud, but although he appeared in various screen adaptations of her work (and the novel Sleeping Murder even involves a visit to one of his stage performances), they never met and he never appeared in one of her plays. Gielgud later became both personally and professionally linked with the H.M. Tennent theatrical empire, and would have been unlikely to put his name to a production by Peter Saunders, Christie’s producer at the height of her playwriting career. Max invited him to speak at Agatha’s memorial service, but he was unable to do so.

As well as its dating, there is a further mystery surrounding the script that Gielgud was responding to. In 1926 Thornton Butterworth published a verse play called Akhnaton by Adelaide Phillpotts, the daughter of Agatha’s mentor Eden Phillpotts. There are striking similarities between Adelaide Phillpotts’ play and Christie’s, over and above the fact that they clearly share source material.

The story of Adelaide Phillpotts is a fascinating one, and would easily fill a book in its own right. An accomplished writer, and the author of forty-two novels, plays and books of poetry, her autobiography, Reverie, was published in 1981 when she was eighty-five, under her married name Adelaide Ross. It tells of her childhood in Torquay, where attending the local theatre was a highlight, her early naïve attempts at playwriting, finishing school in Paris, her adventures in London as a young woman where she became an admirer of Lilian Baylis’ Shakepeare productions at the Old Vic, and her various playwriting collaborations with her father, particularly the 1926 success Yellow Sands. It also makes reference, without recrimination, to the incestuous attentions that her father paid her from an early age, and to the oppressive closeness of both their personal and professional lives, until she finally married, despite his protestations, at the age of fifty-five. After which he never spoke to her again. ‘As to Father,’ concludes Adelaide simply, ‘he should be judged, as he wished, and it must be favourably, by his works.’35

Writing of her life in London in 1925, Adelaide says, ‘I spent several hours in the British Museum Reading-room, where I procured books, recommended by Arthur Weigall, concerning the life and times of Pharaoh Akhnaton, about whom Father had urged me to write a blank verse play – a splendid theme which I had promised to attempt.’36 Weigall was an Egyptologist and theatre set designer who in 1910 had authored the book The Life and Times of Akhnaton, Pharoah of Egypt. Publisher Thornton Butterworth’s Times advertisement for a ‘new and revised edition’ in 1922 trumpeted, ‘“the world’s first idealist” … “the most remarkable figure in the history of the world” … such are some of the praises given to the young Pharaoh of over 3,000 years ago whose strange and pathetic story is here told by the distinguished Egyptologist, Mr Weigall’.37 The author was part of a team that he believed had discovered the mummified remains of Akhnaton, although from my necessarily brief dip into Egyptology it appears that correctly identifying and dating ancient Egyptian remains is a challenge equal only to that of establishing a chronology for the work of Agatha Christie. I suspect that Weigall’s archaic and occasionally melodramatic prose style may have influenced that adopted by Agatha in writing her own play.

Like Agatha’s play, Adelaide’s was never performed, but it was well reviewed in the February 1927 edition of The Bookman:

Some thirty-three hundred years separate the periods of Akhnaton and Yellow Sands. Yet two characters are common to each play – the Pharoah of the one and the socialist of the other. During the war they would have been described – and derided – as Pacifists; in these less disruptive days they may be accepted as idealists … This has not been written to gratify historical or archaeological curiosity, but to display the character and difficulties of a ruler who dared to place himself in opposition to the powerful priestly and military castes of his period. Akhnaton is seen in conflict with all types, from the father he succeeded to the scullions of his kitchen, and in every varied circumstance his character is depicted with unfailing consistency and ever-growing charm. But it is not merely on her interpretation of Akhnaton that Miss Phillpotts is to be congratulated; her sketches of the general Horemheb, of the aggressive sculptor Bek, and of the subtle and wavering High Priest are also drawn with a firm hand. And many of her episodes have a high dramatic quality, which culminates in a scene of great tensity in the tomb of Akhnaton fifteen years after his death. What theatrical producer will enrich the intellectual and moral life of the nation by an adequate performance of this remarkable play?

Eden Phillpotts was delighted by his daughter’s play. He wrote to her from Torquay, ‘My darling dear, I love to have the dedication of the Akhnaton and am very proud to think that you dedicated it to me. It will be my most cherished possession after your dear self and I shall value it beyond measure,’38 and, ‘I gave Mrs Shaw Akhnaton and she was very pleased with the gift and I hope will tell me what she thought of it.’39

Adelaide’s and Agatha’s plays, of course, share much the same cast list of historical characters and both use as their ultimate source material translations of the Armana letters, a remarkable collection of around three hundred ancient Egyptian diplomatic letters, carved on tablets and discovered by locals in the late 1880s. Whilst Adelaide meticulously credits her sources, however, Agatha does not; so it is difficult to tell where they end and her own invention begins. Adelaide’s play is written in accomplished blank verse and Agatha’s in a sort of poetic prose that makes it completely different in style from any of her other writing. Whilst Adelaide’s is arguably the more accomplished literary work, Agatha’s is definitely the more satisfactory as a piece of drama, with more developed intrigue and conflict amongst the courtiers, the dramatic licence of the introduction of the then newsworthy character of Tutankhamun (played as a young adult rather than the child that he would then have been) and, for good measure, a climactic poisoning and suicide (although there is no mystery as to how or why).

Amongst the striking parallels between the plays are the use of Akhnaton’s coffin inscription as his death speech. In Adelaide’s version,

I breathe the sweet breath of thy mouth,

And I behold thy beauty every day …

Oh call my name unto eternity

And it shall never fail (Akhnaton falls back dying)40

And in Agatha’s,

I breathe the sweet breath which comes from thy mouth … Call upon my name to all eternity and it shall never fail (he dies)41

Immediately after this, both plays feature an epilogue set in Akhnaton’s tomb, in which people are erasing Akhnaton’s name and someone gives a speech. In Adelaide’s version,

… A ghost with Amon’s dread wrath upon thy head – eternally forgotten by God and man.

(Priests, raising their torches) Amen! Amen! Amen!

And in Agatha’s,

… So let this criminal be forgotten and let him disappear from the memory of men … (a murmur of assent goes up from the People)

There is a scene in Adelaide’s version where a sequence of messengers read out letters bringing news of military calamity from the far reaches of the empire. In Agatha’s version of what is effectively the same scene, there are no messengers but Akhnaton’s general Horemheb reads out the letters himself. In both cases, the readings are interrupted by a comment from Horemheb. In Adelaide’s version,

My lord, troops disembarked at Simyra

And Byblos, could be quickly marched to Tunip

In Agatha’s,

My lord, it is not too late, Byblos and Simyra are still loyal. We can disembark troops at these ports, march inland to Tunip.

Again, the source material (credited by Adelaide but not by Agatha) is clearly the same, so the similarities in the phraseology are less remarkable than the dramatic construction of an intervention by Horemheb with these words. But perhaps even more notable are some similarities in stage directions. Adelaide: ‘The high priest … with shaven head, wearing a linen gown …’; Agatha: ‘The high priest … his head is closely shaven and he wears a linen robe …’

So, what to make of all this? On one level it may appear that in writing Akhnaton Christie simply ‘did a Vosper’ on the work of her mentor’s daughter. But when Christie’s own play finally saw the light of day in 1973, Adelaide was still very much alive (she died, aged ninety-seven, in 1993); and Christie is unlikely to have allowed its publication in the knowledge that she had consciously borrowed from another living writer’s work. It has to be said, too, that each writer puts her own very distinctive touches into the story. Adelaide includes the characters of Akhnaton’s and Queen Nefertiti’s two daughters, who some historians believe he took as additional wives, with the following exchange between father and daughter as one of them is married off to a young prince:

AKHNATON … I think thou art still a child?

MERYTATON: A woman, my lord.

AKHNATON: Then art thou willing to be wed?

MERYTATON: No sire,

If husband gained mean father lost. But, yes,

If I may keep them both

Christie, on the other hand, explores in some detail the relationship between the artistic, poetry-reciting Akhnaton and his muscular general, Horemheb. One wonders what the Lord Chamberlain’s office would have made of this exchange between the two men:

AKHNATON: (after looking at him a minute) I like you, Horemheb … (Pause) I love you. You have a true simple heart without evil in it. You believe what you have been brought up to believe. You are like a tree. (Touches his arm) How strong your arm is. (Looks affectionately at Horemheb) How firm you stand. Yes, like a tree. And I – I am blown upon by every wind of Heaven. (wildly) Who am I? What am I? (sees Horemheb staring) I see, good Horemheb, that you think I am mad!

HOREMHEB: (embarrassed) No, indeed, Highness. I realize that you have great thoughts – too difficult for me to understand.

As it happens, Adelaide’s was not the first verse play on the subject by a female writer. In 1920 The Wisdom of Akhnaton by A.E. Grantham (Alexandra Ethelreda von Herder) had been published by The Bodley Head, the company that in the same year gave Christie her publishing debut. Grantham’s introduction cites the Amura tablets as her source and advocates the relevance of Akhnaton’s philosophy:

There was no room for greed or hate and war in this conception of man’s destiny; no occasion for those ugly and gratuitous rivalries which make human history such a never-ending tragedy … never has mankind stood in direr need of a real faith in the indestructability and the supreme beauty of this great Pharaoh’s ideals of light and loveliness in life … the episode chosen for dramatisation is the conflict between the claims of peace and war and Akhnaton’s successful struggle to make his people acquiesce in his policy of peace.42

The Bodley Head’s Times advertisement for Grantham’s The Wisdom of Akhnaton read, ‘A remarkable play about Akhnaton, the father of Tutankhamen, and the Pharoah who tried to establish the pure monotheistic religion of Aton and a religion of Love and Peace thirteen hundred years before Christ … this is one of the few works of fiction ever written about the Egypt of those days, which are now being made to live again so vividly by Lord Carnarvon’s discoveries.’43

Despite covering approximately the same period of history and including several of the same characters, however, there are no echoes of Grantham’s work in either Adelaide’s or Agatha’s, a fact which only serves to highlight further the similarities between those of Eden Phillpotts’ two protégées. Whilst Grantham chooses to halt the story at the point where Akhnaton has been ‘successful in his struggle to make his people acquiesce in a policy of peace’, both Adelaide and Agatha go on to show Akhnaton’s ultimately tragic failure. In doing so they are not, in my view, opposed to the value of striving for Akhnaton’s aspirations, even against all the odds and in the face of human nature.

During the First World War, Adelaide had worked for Charles Ogden’s Cambridge Magazine, which controversially gave a balanced view of events by publishing throughout the conflict translated versions of foreign press articles, as well as pieces by writers such as Shaw and Arnold Bennett. By the early 1920s, newspapers were full of reports of the latest archaeological finds in Egypt, and Egyptologists were front page celebrities as they continued to unveil the ‘secrets of the tombs’. Western writers and intellectuals were intrigued by the lessons that could be learned from this ancient culture, particularly in a world still reeling from the devastation of war, and it is little wonder that the Phillpotts circle found the pacifist philosophy of Akhnaton in particular worth exploring, and that at least two female playwrights, A.E. Grantham and Adelaide Phillpotts, thought him a worthy subject for a verse play.

It thus seems plausible that Agatha’s autobiography could well be correct in appearing to date the origins of her own Akhnaton play to the mid-1920s, and that it may have been, at least initially, the product of this post-war zeitgeist and her association with Eden Phillpotts rather than her more specific interest in archaeology in the 1930s. It may even be that it was Phillpotts himself who suggested the idea to Agatha, just as he had to his daughter. Even if one dismisses the similarities between Agatha’s Akhnaton play and Adelaide’s as pure coincidence, there seems to me to be a Phillpotts stamp on the project that is hard to ignore.

In a further twist to the tale, in 1934 Adelaide Phillpotts and her friend and writing partner Jan Stewart wrote a three-act murder mystery play, which was performed in repertory at Northampton. It was called The Wasps’ Nest.44 Like Christie’s at that time unperformed 1932 one-act play of the same title, it revolves around the destruction of a wasp’s nest in a country house and the murderous application of the cyanide used to achieve this. Although the outcome is entirely different, it contains some remarkably similar plot devices to Christie’s story, and shares a storyline about a woman returning to her previous lover having abandoned him in favour of another man.

Did Agatha read Adelaide’s 1926 Akhnaton play? Did Adelaide read Agatha’s 1928 ‘Wasp’s Nest’ short story in the Daily Mail? We do know that Agatha and Adelaide exchanged some affectionate correspondence in the late 1960s, in which the two old ladies charmingly reminisced about their Torquay childhoods and shared news of family and friends.45 There is no mention at all of matters Egyptian. Or of wasps.

Another long-term playwriting project of Christie’s was the compelling domestic drama, A Daughter’s a Daughter, which she wrote in the 1930s but which was not to receive its premiere until 1956. Taking its title from the saying, ‘Your son’s a son till he gets a wife, but a daughter’s a daughter all your life’, it concerns the friction between a widow, Anne Prentice, and her adult daughter, Sarah, as each in turn contrives to destroy the other’s opportunities to find fulfilment in love. As with The Lie and The Stranger, we see a young woman torn between a dull but reliable suitor and the excitement of a potentially more dangerous liaison.

In the third week of March 1939, a letter from Bernard Merivale, Edmund Cork’s business partner at Hughes Massie, landed on the desk of Basil Dean.

Dear Basil Dean,

I would be very glad if you would read the enclosed play by Agatha Christie.

The play has nothing whatever to do with Poirot or crime solution. It impresses me as being another manifestation of this author’s undoubted genius.

I would be very interested to know your reaction.46

Dean appears to have responded positively although, sadly, his side of the correspondence is in the missing early years of Hughes Massie’s Christie archive. Merivale acknowledged his ‘interesting letter’ about the play, and on 5 April Agatha sent Dean a handwritten note from Sheffield Terrace: