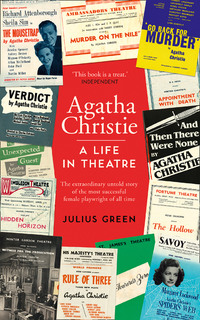

Agatha Christie: A Life in Theatre

The ending of ReandeaN was not a good thing for either partner, says Basil Dean in his autobiography:

Alec Rea, its financial head, loved the theatre, not because he was a playwright manqué, not because of some professional diva whose interests he sought to advance, but for its own sake. Yet he never really understood it, and his judgement of plays was poor, as the subsequent record shows. He was suspicious of plays breaking fresh ground, especially if they revealed leftist tendencies, a surprising trait in a member of a distinguished Liberal family. His rejection of Shaw’s Heartbreak House was a case in point. Generally speaking, the plays he produced during the remainder of his tenancy of the St Martin’s Theatre with Paul Clift as his manager, lacked distinction and brought only limited commercial success. Yet he deserves high place in the annals of the English Theatre, for as Patrick Hastings [an MP and barrister who wrote plays produced by ReandeaN] pointed out in his autobiography: ‘ReandeaN was virtually the last organised management under a private patron.’

The parting was largely my fault. I should have restrained my impatience to conquer on so many fields at once … When all’s said I owe Alec Rea an incalculable debt, for without his warm friendship and loyal support during my early struggles I might not have achieved anything very much.18

After the end of ReandeaN, Alec Rea and Basil Dean continued to be linked by a number of joint business ventures, but the partnership was effectively over. Rea’s new company, Reandco, continued its involvement with the St Martin’s and then, in September 1930, announced that it had also taken over the lease of the Embassy Theatre in Swiss Cottage and was establishing a repertory company there, a move that was widely welcomed in the theatrical community. Sydney W. Carroll, who two years later was himself to found the Regents Park Open Air Theatre, wrote in the Daily Telegraph, under the heading ‘Latest Repertory Idea’,

Keep both eyes on the Embassy Theatre, Swiss Cottage, Hampstead. It is a beacon flaming on the heights that overlook London. It can only be seen, at the moment, gallantly flickering through the fog. But when the mists break and the sky grows clear the blaze will be apparent to all theatre lovers, brilliant and leaping to the sky … It is a Repertory venture, and out of repertory and repertory alone will come salvation for modern theatre. The Embassy has recently been taken over by Alec L. Rea, a manager who has been creditably associated with the repertory movement for years, first chairman of the Liverpool Repertory Company, a position he held for six years, and who, in conjunction with Basil Dean, has been identified with some of the most notable and distinguished productions in the West-end theatre of recent years.

Mr Rea believes, as I do, that actors must be properly and thoroughly trained. They must get constant exercise in their craft. And repertory, with its quick succession of different experiences in play by play, offers the young actor and actress the ideal and only public opportunity for a thorough practical grounding in the actor’s art. Nothing is more deadening to the mind, the soul, and the sensibilities of a player than to be compelled to enact the same role night after night for months …

Mr Rea is ambitious of finding, with the aid of the Embassy, new players, new dramatists with original ideas. He hopes after the fashion of Miss Horniman at Manchester to found a school of young playwrights. He has catholic tastes and aspirations. His arms embrace equally both classic and commercial. He will do his best to encourage both highbrow and box-office alternately in the hope of making a unison ultimately between them …19

The Embassy Theatre had opened in 1928 in a building that had originally housed the Hampstead Conservatoire of Music. It initially operated as a ‘try-out house’, much like the ‘Q’ Theatre at Kew Bridge, giving often challenging plays a run of a fortnight in the hope that they might prove attractive to West End managements; but prior to Rea’s takeover its programming had become increasingly ad hoc. The short-lived Everyman Theatre in nearby Hampstead had served much the same purpose from 1920 to 1926, and had enjoyed a number of West End transfers before a succession of box office failures forced its closure; and it is the Everyman that Christie erroneously credits in her autobiography as the theatre which premiered her own play. Such theatres always found it difficult to maintain a permanent company of actors on the salaries they could offer, and it was Rea’s commitment to establishing a full-time team of players at the Embassy in a proper two-weekly repertory system that endeared him to the theatrical establishment.

The permanent ensemble of performers, who Sydney W. Carroll described as ‘remarkably talented’, included Joyce Bland, Judy Menteath, Francis L. Sullivan, John Boxer and Donald Wolfit, all of whom were to appear in Christie’s play, and Andre van Gyseghem, who directed it. Robert Donat also appeared regularly, though not in this particular production, and further performers were engaged on a show-by-show basis as required. ‘These facts,’ concludes Carroll, ‘are of sufficient importance and interest to justify circulation all over Greater London. Already, I understand, people are coming from considerable distances to see the art of these players, and my own experience of their work leads me cordially to recommend them to the public patronage.’

Rea’s creative partner in the venture was A.R. Whatmore, who had been running the Hull Repertory Theatre Company to great acclaim for the previous six years. And, of course, if any of the productions did merit a West End transfer, then Rea still owned the lease on the St Martin’s, so such a thing would be easy enough to facilitate.

Agatha’s excitement at being included in the opening season of this widely publicised venture was justified. In an early November 1930 letter to Max, who had returned to the excavations at Ur, she wrote: ‘Very exciting – I heard this morning an aged play of mine is going to be done at the Embassy Theatre for a fortnight with the chance of being given West End production by the Reandco – of course nothing may come of it – but it’s exciting anyway – shall have to go to town for a rehearsal or two end of November, I suspect – I wish you were here to share the fun (and the agony when things go wrong and everyone forgets their part!!) But it’s awfully fun all the same.’20

After Dinner was licensed to Reandco on 18 November 1930, for a two-week try-out at the Embassy Theatre within three months, with a West End option to be taken up within six weeks of the Embassy production on payment of £100. The Lord Chamberlain’s office issued a licence on 4 December to the play – which was now called Black Coffee, the title having been changed by hand on the script they received21 and the production opened on 8 December. To today’s theatre producers these lead-times would seem unfeasible, but with a permanent company on retainer, and rehearsing the next show whilst playing the current one, the repertory system allowed for the confirmation of future programming to be left until the very last minute. The extraordinary logistics of scheduling in the London and regional repertory theatres and London ‘try-out’ theatres at this time, and the manner in which they constantly fed new productions into the West End system alongside a seemingly inexhaustible supply of new plays generated by the West End’s own managements, all of it without the benefit of a penny of public subsidy, makes the operation of today’s theatre industry look positively leisurely.

On 26 November Agatha wrote to Max from Ashfield: ‘“After Dinner” or (according to my Sunday Times which seems to know more than I do!) “Black Coffee” – comes on on Dec 8th so I will have to go up to town for rehearsals next week … Six eminent detective story writers have been asked to broadcast again – we’re all getting together on December 5th to plan the thing out a bit – Me, Dorothy Sayers, Clemence Dane, Anthony Berkeley EC Bentley and Freeman Wills Croft … all rather fun.’22

Here she is referring to a project which was to be broadcast on the radio in early 1931, in which members of the Detection Club created a sort of literary game of consequences, each writing and broadcasting an episode of a crime story which was to be aired over a number of weeks. The Detection Club, comprising the elite of British crime writers, had undertaken a similar project with great success in 1930, and the authors contributed their income from the BBC to the club’s coffers.

In 1928 Clemence Dane had co-authored with Helen Simpson the first of two crime novels she was to pen, Enter Sir John, about an actress wrongly convicted of murder. Filmed as Murder! by Alfred Hitchcock in 1930, it earned Dane a place in the Detection Club. I do hope that Agatha and Clemence Dane did actually meet on 5 December. The successful forty-two-year-old playwright who had just published her first detective novel and the successful forty-year-old detective novelist, who was about to have her own first play performed, would have got on well, I think. Clemence Dane’s name appears on a reading list of Agatha’s in one of her notebooks.

The opening night of Black Coffee at the Embassy was a success. Although Max was absent, Agatha’s sister Madge was in the audience, just as Agatha had been for The Claimant six years previously, and with Madge was her husband, James, along with his sister Nan and her husband George Kon. Agatha wrote to Max two days after the opening:

Oh it has all been fun – Black Coffee. I mean it was fun going to rehearsals and everything went splendidly on the night itself except that when the girl said (in great agitation!): ‘This door won’t open!’ it immediately did! Something like that always happens on a first night. They had a larger audience … than they’ve ever had before, and the Repertory Company were so pleased … The girl was awfully good – couldn’t have had anyone better – well, let us hope ‘something will come of it’ as they say – preferably in May. The Reandco have an option for six months. I do hope they take it up. This week has been simply hectic.23

The actress she so admired playing the role of Lucia Amory was Joyce Bland, who had just completed a busy and successful season at Stratford. Agatha was wrong about the length of the West End option; Reandco actually had six weeks in which to take it up, and they did, although a log-jam of productions at the St Martin’s meant that, following the two-week run at the Embassy in December 1930, the play would not appear in the West End until the following April.

Although there is a sub-plot relating to spies, and a remarkably prescient storyline relating to weapons of mass destruction created by ‘disintegration of the atom’, Black Coffee is, to all intents and purposes, an efficient and well-crafted, if relatively simple, country house murder mystery. It engages both some of the plot devices and some of the characters – not only Poirot but also Captain Hastings and Inspector Japp – who, at the most likely time of the play’s writing, had just been introduced to the public in Christie’s first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Black Coffee thus ticks all the boxes for a ‘typical Agatha Christie play’ and, ironically, was both the first and last that she wrote in this idiom.

As with Alibi, Christie’s own principal concern was with the portrayal of Poirot. Although she ultimately preferred Francis L. Sullivan’s interpretation to Charles Laughton’s, she laments in her autobiography, ‘It always seems strange to me that whoever plays Poirot is always an outsize man. Charles Laughton had plenty of avoirdupois, and Francis Sullivan was broad, thick and about 6’2” tall.’24

Sullivan, like Laughton, saw Poirot as an ideal vehicle for his talents, and had actually first performed the role in the post-West End tour of Alibi. In fact he made something of a career of being the poor man’s Charles Laughton, not only taking over his role in Alibi but also starring in a 1942 revival of A Man With Red Hair. Sullivan would receive his final ‘review’ in 1956 in the form of his Times obituary, which opined, ‘Corpulence, sharp eyes embedded in florid features, and a deep, plummy voice suited him admirably for the part of the suave but foxy lawyer. He was generally too much of a caricature to be unrelievedly sinister, and though he was sometimes cast as a comic, his talents were wasted if there was no streak of evil in the part. His acting had a wider range than his exaggerated physique might suggest. He was an obvious choice for Bottom, and perhaps for Mr Bumble, but not for Hercule Poirot …’25

Although Christie had objected to the amorous antics of a French ‘Beau Poirot’ in Alibi, she was not above introducing an element of romantic frisson when it came to her own portrayal of her Belgian sleuth. Here are the final moments of Alibi, as performed by Charles Laughton:

CARYL (softly) I don’t care what anyone says, you will always be “Beau Poirot” to me! (holds out her hand) Good-night!

POIROT: (Taking both her hands, kisses first one, then the other) Good-bye. (Still holding her hands) Believe me, Mees

Caryl, I do everything possible to be of service to you!

(drops her hands)

(CARYL goes out)

Good-bye!

POIROT stands at the open window looking out after her as the Curtain slowly falls.26

And here are the not dissimilar final moments of Black Coffee, written several years before Alibi, in the original script approved by the Lord Chamberlain and performed by Francis L. Sullivan at the Embassy:

LUCIA: M Poirot – (she holds out both hands to him)

Do not think that I shall ever forget …

(Lucia raises her face. Poirot kisses her.)

(She goes back to Richard [her husband]. Lucia and Richard go out together … Poirot mechanically straightens things on the centre table but with his eyes fixed on the door through which Lucia has passed.)

POIROT: Neither – shall I – forget.27

Reviews from the Embassy, as with Alibi, inevitably focused largely on the interpretation of Poirot. ‘Mr Sullivan is obviously very happy in the part, and his contribution to the evening’s entertainment is a considerable one,’ said The Times.28 Amongst the other characters are Dr Carelli – played at the Embassy by Donald Wolfit – the archetypal Christie ‘unexpected guest’ who has echoes in The Mousetrap’s Mr Paravicini; and, more interestingly, a wittily executed portrayal of a young ‘flapper’ girl, the murder victim’s niece. The flapper phenomenon was at its height in 1922, as a generation of young women threw off the restrictions of the Victorian and Edwardian era and defined their own agenda in terms of fashion, entertainment and social interaction with men. The sexual revolution of the 1920s, in its subversion of what went before it, was arguably far more radical than anything that happened in the 1960s, and although Agatha herself would have been a decade too old to qualify as a flapper or to embrace their style and philosophy, there is a distinct affection in her writing for what they stood for, albeit informed by her trademark observational humour. In Black Coffee, Barbara Amory is described as ‘an extremely modern young woman of twenty-one’. She dances to records on the gramophone and flirts mercilessly with Hastings, describing him as ‘pre-war’ (‘Victorian’ in the original script) and exhorting him to ‘come and be vamped’. When criticised by her aunt for the brightness of her lipstick, she responds, ‘take it from me, a girl simply can’t have too much red on her lips. She never knows how much she is going to lose in the taxi coming home.’

When the play did finally open in the West End, at the St Martin’s Theatre, it was in a much-changed production. Christie had undertaken rewrites, as she had felt that her ‘aged’ play seemed out of date when she saw it at the Embassy. ‘Have been working very hard on Black Coffee. Some scenes were a little old fashioned, I thought,’29 she wrote to Max. Tricks she uses in order to achieve a more ‘contemporary’ feel include a joke about the brand-name vitamins Bemax, which were advertised widely in 1930. The script published by Arthur Ashley in 1934 included these changes, along with the following more straight-laced version of the final scene:

LUCIA: (Down to Poirot, takes his hand, she also has Richard’s hand) M.Poirot, do not think I shall forget – ever.

POIROT: Neither shall I forget (kisses her hand.)

(Lucia and Richard go out together through window. [Poirot] follows them to window, and calls out after them.)

POIROT: Bless you, mes enfants! Ah-h!

(Moves to the fireplace, clicks his tongue and straightens the spill vases.)30

At the Embassy, Black Coffee had been directed by Andre van Gyseghem, a radical young director who, as a RADA-trained actor, had worked for the theatre’s creative head A.R. Whatmore in his previous post at the Hull Repertory Theatre. A leading light of the Workers’ Theatre Movement, van Gyseghem was to become a member of the Communist Party and a frequent visitor to the Soviet Union, and later penned a surprisingly readable book entitled Theatre in Soviet Russia (1943). The West End production of Black Coffee was redirected by Oxford-educated Douglas Clarke-Smith, an actor-director who appears to have had no association with the Embassy, but who had cut his teeth at Birmingham Rep after distinguished service in the First World War, and who went on to direct over twenty productions for pioneering touring group the Lena Ashwell Players, the peacetime incarnation of the company that had provided entertainment for the troops throughout the conflict.

As well as a new director, all but one of the supporting cast to Sullivan’s Poirot were also new to the piece. Joyce Bland was amongst those who were replaced, along with van Gyseghem himself, who had doubled his directing duties with the small but significant role of Edward Raynor. Given that the delay in transferring had allowed for the luxury of a new rehearsal period, the Embassy had clearly decided not to commit too many of their core ensemble to a potentially lengthy West End run. On 9 April 1931, the day Alec Rea presented the West End premiere of Black Coffee, The Times was listing attractions at thirty-one West End theatres, including revivals of Shaw’s Man and Superman at the Court, Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler at the Fortune and Somerset Maugham’s The Circle at the Vaudeville. At the Queen’s Theatre, Rudolf Besier’s The Barretts of Wimpole Street, directed by Barry Jackson, was advertising itself as ‘London’s Longest Run’ (which, of the productions then running in London, it was; it went on to complete 530 performances).

In the end, Black Coffee itself was to enjoy only a very short West End run. Reviews of the new production were not unfavourable, and the Observer’s influential Ivor Brown noted, ‘Mr Francis Sullivan prudently refraining from a Charles Laughton pastiche does not tie the “character” labels all over the part, but plays it quietly and firmly, trusting that the story will do its own work of entertainment.’ But he concluded, ‘Black Coffee is supposed to be a strong stimulant and powerful enemy of sleep. I found the title optimistic.’31

Reandco soon found that they needed the St Martin’s in order to gain a West End foothold for another production; as The Times reported: ‘In order that Messrs. Reandco may present Mr Ronald Jeans’s new play Lean Harvest at the St Martin’s Theatre on Thursday next, Mrs Agatha Christie’s play Black Coffee will be transferred on Monday to the Wimbledon Theatre, and on the following Monday, May 11, it will resume its interrupted run at the Little Theatre.’32 Although Reandco owned the lease on the St Martin’s, Bertie Meyer remained the building’s licensee on behalf of its freeholders, the Willoughby de Broke family. Having enjoyed a successful association with the Little Theatre as a producer, he was doubtless instrumental in facilitating Black Coffee’s transfer there, although he was not directly involved with the production. Black Coffee was sent away from the West End to Wimbledon in order to fill an unsatisfactory week’s gap between its scheduling at the St Martin’s and the Little. But the production never really recovered from this disruption, and closed on 13 June.

Between the St Martin’s and the Little Theatre, Black Coffee had completed a total of sixty-seven West End performances over two months, which was, at least, slightly longer than The Claimant’s run. It was to be more than twenty years until the premiere of the next Christie play that was not based on one of her novels.

Agatha herself had missed her West End debut as a playwright in order to join her new husband at the archaeological dig in Ur. In the autumn of 1931 Max Mallowan relocated his archaeological work in Iraq to Nineveh, and at Christmas Agatha hurried home in the hope of catching the premiere of Chimneys, which Reandco had now scheduled for a December opening at the Embassy, clearly in the hope of enabling a West End transfer as they had done the previous year with Black Coffee.

The fate of Chimneys has taken on an almost mythical status amongst Christie scholars as a ‘play that never was’. Having been advertised as opening at the Embassy, gone into rehearsal and been licensed by the Lord Chamberlain, it suddenly disappeared from their schedule, apparently without explanation. It was not heard of again until it was unearthed by Canadian director John Paul Fishbach in 2001 and given its world premiere in Calgary in 2003, almost twenty-eight years after Christie’s death. As is often the case with matters theatrical, however, the reality of the ‘Chimneys mystery’ was far more prosaic than may at first appear, and those previously attempting to establish the facts of the matter may have enjoyed more success if Agatha had dated her letters with the year as well as the day and month. Once her letters are placed in the correct sequence, the order of events surrounding the cancelled production becomes apparent.

There are in fact no fewer than four copies of the script amongst Christie’s papers, all of them very similar. Three of these are duplicates, two clearly dated 5 July 1928 by the Marshall’s typing agency stamp and carrying Agatha’s address in Ashfield, Torquay. The unstamped duplicate carries the Hughes Massie label and has been annotated in pencil by the actress playing the role of Bundle. The fourth copy includes some slight variations in the typescript and handwritten notes by Agatha, and has the Hughes Massie address handwritten on it. The first point to establish, therefore, is that the script itself never actually ‘disappeared’, even if the scheduled premiere production appears to have done; assuming that Fishbach’s copy is now amongst those at the archive, we know of at least four other ‘originals’, including the one lodged with the Lord Chamberlain’s office. Hughes Massie’s records show that Reandco acquired the rights in the play as early as 22 April 1931, shortly after the opening of their West End run of Black Coffee, for production at the Embassy Theatre within six months of signature and with a West End option to be taken up within six weeks of the Embassy production.33 This time the sale had been co-ordinated by Hughes Massie themselves. As was standard practice, the royalties payable by the Embassy, as a small repertory theatre, were at the reduced rate of 5 per cent of box office income. Although the scheduling of the production would be subject to the vagaries of the repertory system and its short lead times, Reandco clearly wanted to ensure that the next Christie play would appear as part of their own repertoire rather than someone else’s.

The Times of Thursday 19 November 1931 duly announced that ‘The next production at the Embassy Theatre will be Chimneys, by Agatha Christie, which Mr A.R. Whatmore will produce [i.e. direct] on Thursday 1 December.’ This was slightly outside their six-month option period, but that would not have been an issue for a management of good standing who had given Christie her West End premiere, and an informal extension of the option had doubtless been negotiated. Based on the previous year’s experience, Rea and Whatmore clearly felt that a pre-Christmas Christie at the Embassy was a good formula for box-office success.