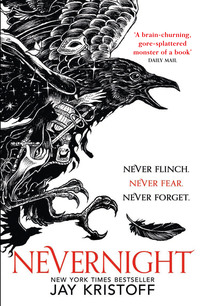

The Nevernight Chronicle

It was thin as old vellum. A shape cut from a ribbon of darkness, not quite solid enough that they couldn’t see the deck behind it. Its voice was the murmur of satin sheets on cold skin.

‘… i fear you picked the wrong girl to dance with …’ it said.

A chill stole over them, whisper-light and shivering. Movement drew Peacock’s eyes to the deck, and he realised with growing horror that the girl’s shadow was much larger than it should, or indeed could have been. And worse, it was moving.

Peacock’s mouth opened as she introduced her boot to his partner’s groin, kicking him hard enough to cripple his unborn children. She seized the walnut thug’s arm as he doubled up, flipping him over the railing and into the sea. Peacock cursed as she moved behind him, but he found he couldn’t shift footing to match her – as if his boots were glued in the girl’s shadow on the deck. She kicked him hard in his backside and he toppled face-first into the rails, spreading his nose across his cheeks like bloodberry jam. The girl spun him, knife to throat, pushing him against the railing with his spine cruelly bent.

‘I beg pardon, miss,’ he gasped. ‘Aa’s truth, I meant no offence.’

‘What is your name, sir?’

‘Maxinius,’ he whispered. ‘Maxinius, if it please you.’

‘Do you know what I am, Maxinius-If-It-Please-You?’

‘… D-da …’

His voice trembled. His gaze flickering to shadows shifting at her feet.

‘Darkin.’

In his next breath, Peacock saw his little life stacked before his eyes. All the wrongs and the rights. All the failures and triumphs and in-betweens. The girl felt a familiar shape at her shoulder – a flicker of sadness. The cat who was not a cat, perched now on her clavicle, just as it had perched on the hangman’s bedhead as she delivered him to the Maw. And though it had no eyes, she could tell it watched the lifetime in Peacock’s pupils, enraptured like a child before a puppet show.

Now understand; she could have spared this boy. And your narrator could just as easily lie to you at this juncture – some charlatan’s ruse to cast our girl in a sympathetic light.fn8 But the truth is, gentlefriends, she didn’t spare him. Yet, perhaps you’ll take solace in the fact that at least she paused. Not to gloat. Not to savour.

To pray.

‘Hear me, Niah,’ she whispered. ‘Hear me, Mother. This flesh your feast. This blood your wine. This life, this end, my gift to you. Hold him close.’

A gentle shove, sending him over into the gnashing swell. As the peacock’s feather sank beneath the water, she began shouting over the roaring winds, loud as devils in the Maw. Man overboard! She screamed. Man overboard! And soon the bells were all a-ringing. But by the time the Beau turned about, no sign of Peacock or the walnut bag could be found among the waves.

And as simple as that, our girl’s tally of endings had multiplied threefold.

Pebbles to avalanches.

The Beau’s captain was a Dweymeri named Wolfeater, seven feet tall with dark locks knotted by salt. The good captain was understandably put out by his crewmen’s early disembarkation, and keen on hows and whys. But when questioned in his cabin, the small, pale girl who sounded the alarm only mumbled of a struggle between the Itreyans, ending in a tumble of knuckles and curses sending both overboard to sailor’s graves. The odds that two seadogs – even Itreyan fools – had tussled themselves into the drink were slim. But thinner still were the chances this girlchild had gifted both to Trelene all by her lonesome.

The captain towered over her; this waif in grey and white, wreathed in the scent of burned cloves. He knew neither who she was nor why she journeyed to Ashkah. But as he propped a drakebone pipe on his lips and struck a flintbox to light his tar, he found himself glancing at the deck. At the shadow coiled about this strange girl’s feet.

‘Best be keeping yourself to yourself ’til trip’s end, lass.’ He exhaled into the gloom between them. ‘I’ll have meals sent to your room.’

The girl looked him over, eyes black as the Maw. She glanced down at her shadow, dark enough for two. And she agreed with the Wolfeater’s assessment, her smile sweet as honeydew.

Captains are usually clever fellows, after all.

CHAPTER 3

HOPELESS

Something had followed her from that place. The place above the music where her father died. Something hungry. A blind, grub consciousness, dreaming of shoulders crowned with translucent wings. And she, who would gift them.

The little girl had slumped on a palatial bed in her mother’s chambers, cheeks wet with tears. Her brother lay beside her, wrapped in swaddling and blinking with his big black eyes. The babe understood none of what was going on about him. Too young to know his father had ended, and all the world beside him.

The little girl envied him.

Their apartments sat high within the hollow of the second Rib, ornate friezes carved into walls of ancient gravebone. Looking out the leadlight window, she could see the third and fifth Ribs opposite, looming above the Spine hundreds of feet below. Nevernight winds howled about the petrified towers, bringing cool in from the waters of the bay.

Opulence dripped on the floor; all crushed red velvet and artistry from the four corners of the Itreyan Republic. Moving mekwerk sculpture from the Iron Collegium. Million-stitch tapestries woven by the blind propheteers of Vaan. A chandelier of pure Dweymeri crystal. Servants moved in a storm of soft dresses and drying tears, and at the eye stood the Dona Corvere, bidding them move, move, for the love of Aa, move.

The little girl had sat on the bed beside her brother. A black tomcat was pressed to her chest, purring softly. But he’d puffed up and spat when he saw a deeper shadow at the curtain’s feet. Claws dug into his girl’s hands and she’d dropped him into the path of an oncoming maidservant, who fell with a shriek. Dona Corvere turned on her daughter, regal and furious.

‘Mia Corvere, keep that wretched animal out from underfoot or we’ll leave it behind!’

And as simple as that, we have her name.

Mia.

‘Captain Puddles isn’t filthy,’ Mia had said, almost to herself. fn1

A boy in his middling teens entered the room, red-faced from his dash up the stairs. Heraldry of the Familia Corvere was embroidered on his doublet; a black crow in flight against a red sky, crossed swords below.

‘Mi Dona, forgive me. Consul Scaeva has demanded—’

Heavy footfalls stilled his tongue. The doors swept aside and the room filled with men in snow-white armour, crimson plumes on their helms; Luminatii they were called, you may recall. They reminded little Mia of her father. The biggest man she’d ever seen led them, a trimmed beard framing wolfish features, animal cunning twinkling in his gaze.

Among the Luminatii stood the beautiful consul with his black eyes and purple robes – the man who’d spoken ‘… Death’ and smiled as the floor fell away beneath her father’s feet. Servants faded into the background, leaving Mia’s mother as a solitary figure amid that sea of snow and blood. Tall and beautiful and utterly alone.

Mia climbed off the bed, slipped to her mother’s side, and took her hand.

‘Dona Corvere.’ The consul covered his heart with ring-studded fingers. ‘I offer condolences in this time of trial. May the Everseeing keep you always in the Light.’

‘Your generosity humbles me, Consul Scaeva. Aa bless you for your kindness.’

‘I am truly grieved, Mi Dona. Your Darius served the Republic with distinction before his fall from grace. A public execution is always a tawdry affair. But what else is to be done with a general who marches against his own capital? Or the justicus who’d have placed a crown upon that general’s head?’

The consul looked around the room, took in the servants, the luggage, the disarray.

‘You are leaving us?’

‘I take my husband’s body to be buried at Crow’s Nest, in the crypt of his familia.’

‘Have you asked permission of Justicus Remus?’

‘I congratulate our new justicus on his promotion.’ A glance at the wolfish one. ‘My husband’s cloak fits him well. But why would I need him to grant my passage?’

‘Not permission to leave the city, Mi Dona. Permission to bury your Darius. I am unsure if Justicus Remus wishes a traitor’s corpse rotting in his basement.’

Realization dawned in the Dona’s face. ‘You would not dare …’

‘I?’ The consul raised one sculpted eyebrow. ‘This is the will of the Senate, Dona Corvere. Justicus Remus has been rewarded your late husband’s estates for uncovering his heinous plot against the Republic. Any loyal citizen would see it fitting tithe.’

Murder gleamed in the Dona’s eyes. She glanced at the loitering servants.

‘Leave us.’

The girls scuttled from the room. Glancing at the Luminatii, Dona Corvere aimed a pointed stare at the consul. It seemed to Mia the man wavered in his certainty, yet finally, he nodded to the wolfish one.

‘Await me outside, Justicus.’

The hulking Luminatii glanced at her mother. Down to the girl. Hands large enough to envelop her entire head twitched. The girl stared back.

Never flinch. Never fear.

‘Luminus Invicta, Consul.’ Remus nodded to his men, and amid the synchronised tromp tromp of heavy boots, the room found itself emptied of all but three people.fn2

The Dona Corvere’s voice was a fresh-sharpened knife into overripe fruit.

‘What do you want, Julius?’

‘You know it full well, Alinne. I want what is mine.’

‘You have what is yours. Your hollow victory. Your precious Republic. I trust it keeps you warm at night.’

Consul Julius looked down at Mia, his smile dark as bruises. ‘Would you like to know what keeps me warm at night, little one?’

‘Do not look at her. Do not speak to—’

His slap whipped her head to one side, dark hair flowing like tattered ribbons. And before Mia could blink, her mother had drawn a long, gravebone blade from her sleeve, its hilt crafted like a crow with red amber eyes. Quick as silver, she pressed it to the consul’s throat, his handprint on her face twisting as she snarled.

‘Touch me again and I’ll cut your fucking throat, whoreson.’

Scaeva didn’t flinch.

‘You can drag the girl from the gutter, but never the gutter from the girl.’ He smiled with perfect teeth, glanced at Mia. ‘But you know the price your loved ones would pay if you pressed that blade any deeper. Your political allies have abandoned you. Romero. Juliannus. Gracius. Even Florenti himself has fled Godsgrave. You are alone, my beauty.’

‘I am not your—’

Scaeva slapped the stiletto away, sent it skittering across the floor to the shadow beneath the curtain. Stepping closer, his eyes narrowed.

‘You should envy your dear Darius, Alinne. I showed him a mercy. There will be no hangman’s gift for you. Just an oubliette in the Philosopher’s Stone, and dark a lifetime long. And as you go blind in the black, sweet Mother Time will lay claim your beauty, and your will, and your thin conviction you were anything more than Liisian shit wrapped in Itreyan silk.’

Their lips were so close they almost touched. Eyes searching hers.

‘But I will spare your family, Alinne. I will spare them if you plead me for it.’

‘She’s ten years old, Julius. You wouldn’t—’

‘Would I not? Know me so well, do you?’

Mia looked up at her mother. Tears welling in her eyes.

‘What is it you told me, Alinne? “Neh diis lus’a, lus diis’a”?’

‘… Mother?’ Mia said.

‘One word and your daughter will be safe. I swear it.’

‘Mother?’

‘Julius …’

‘Yes?’

‘I …’

There is a breed of arachnid in Vaan known as the wellspring spider.

The females are black as truedark, and possessed of the most astonishing maternal instinct in the animal republic. Once impregnated, a female builds a larder, stocks it with corpses, then seals herself inside. If the nest is set ablaze, she’ll burn to death rather than abandon it. If beset by a predator, she’ll die defending her clutch. But so fierce is her refusal to leave her young, once her eggs are laid, she won’t move, even to hunt. And herein lies the wellspring’s claim to the title of fiercest mother in the Republic. For once she’s devoured all the stores within her larder, the female begins devouring herself.

One leg at a time.

Plucking her limbs from her thorax. Eating only enough to sustain her vigil. Ripping and chewing until only one leg remains, clinging to the silken treasure trove swelling beneath her. And when her babies hatch, spilling from the strands she so lovingly wrapped them inside, they partake, there and then, of their very first meal.

The mother who bore them.

I tell you now, gentlefriend, and I vow it true, the fiercest wellspring spider in all the Republic had nothing – I say nothing – on Alinne Corvere.

There in that O, so tiny room, Mia felt her mother’s fists clench.

Pride tightening her jaw.

Agony brightening her eyes.

‘Please,’ the Dona finally hissed, as if the very word burned her. ‘Spare her, Julius.’

A victorious smile, bright as all three suns. The beautiful consul backed away, black eyes never leaving her mother’s. He called as he reached the doorway, robes flowing about him like smoke. And without a word, the Luminatii marched back into the room. The wolfish one tore Mia from her mother’s skirts. Captain Puddles mreowled protest. Mia clutched the tom tightly, tears burning her eyes.

‘Stop it! Don’t touch my mother!’

‘Dona Corvere, I bind you by book and chain for crimes of conspiracy and treason against the Itreyan Republic. You will accompany us to the Philosopher’s Stone.’

Irons were slapped around the dona’s wrists, screwed tight enough to make her wince. The wolfish one turned to the consul, glanced at Mia with a question in his eyes.

‘The children?’

The consul glanced to little Jonnen, still wrapped in his swaddling on the bed.

‘The babe is still at the breast. He can accompany his mother to the Stone.’

‘And the girl?’

‘You promised, Julius!’ Dona Corvere struggled in the Luminatii’s grip. ‘You swore!’

Scaeva acted as if the woman had never spoken. He looked down at Mia, sobbing at the foot of the bed, Captain Puddles clutched to her thin chest.

‘Did your mother ever teach you to swim, little one?’

Trelene’s Beau spat Mia onto a miserable pier, jutting from the nethers of a ruined port known as Last Hope. Buildings littered the ocean’s edge like a prizefighter’s teeth, a stone garrison tower and outlying farms completed the oil painting. The populace consisted of fishermen, farmers, a particularly foolish brand of fortune hunter who earned a living raiding old Ashkahi ruins, and a slightly more intelligent variant who made their coin looting the corpses of colleagues.

As she stepped onto the jetty, Mia saw three bent fishermen lurking around a rod and a bottle of green ginger wine. The men looked at her the way maggots eye rotten meat. The girl stared at each in turn, waiting to see if any would offer to dance.fn3

Wolfeater clomped down the gangplank, several crew in tow. The captain noted the hungry stares fixed on the girl – sixteen years old, alone, armed only with a pig-sticker. Propping one boot on a jetty stump, the big Dweymeri lit his pipe, wiped sweat from tattooed cheeks.

‘It’s the smallest spiders that have the darkest poison, lads,’ he warned the fishermen.

Wolfeater’s word seemed to carry some weight among the scoundrels, as they turned back to the water, slurping and bubbling against the jetty’s legs.

Mildly disappointed, the girl offered the captain her hand.

‘My thanks for your hospitality, sir.’

Wolfeater stared at her outstretched fingers, exhaled a lungful of pale grey.

‘Few enough reasons folk come to old Ashkah, lass. Fewer still a girl like you would brave parts this grim. And I’ve no wish to cause offence. But I’ll not touch your hand.’

‘And why is that, sir?’

‘Because I know the name of the ones who touched it first.’ He glanced at her shadow, fingering the draketooth necklace at his throat. ‘If such things have names. I know for damned sure they have memories, and I’ll not have them remember mine.’

The girl smiled soft. Put her hand back to her belt.

‘Trelene watch over you, then, Captain.’

‘Blue below and blue above you, girl.’

She turned and stalked down the pier, the glare of a single sun in her eyes, looking for the building Mercurio had named for her. With heart in throat, she found it soon enough – a dishevelled little establishment at the water’s crust. A creaking sign above the doorway identified it as the Old Imperial. A sign in one filthy window informed Mia ‘Help’ was, in fact, ‘Wonted.’

It was a bucktoothed little shithole, and no mistake. Not the most miserable building in all creation.fn4 But if the inn were a man and you stumbled on him in a bar, you’d be forgiven for assuming he had – after agreeing enthusiastically to his wife’s request to bring another woman into their marriage bed – discovered his bride making up a pallet for him in the guest room.

The girl padded up to the bar, her back as close to the wall as she could get it. A dozen or so folk had escaped the turn’s heat inside – a few locals and a handful of well-armed tomb-raiders. All in the room stopped to stare as she entered; if anyone had been manning the old harpsichord in the corner, they’d surely have hit a wrong note for dramatic effect, but alas, the beast hadn’t uttered a squeak in years.fn5

The Imperial’s proprietor seemed a harmless fellow – almost out of place in this town on the edge of the abyss. His eyes were a little too close together, and he reeked of rotten fish, but considering the stories Mia had heard about the Ashkahi Whisperwastes, she was just glad the fellow didn’t have tentacles. He was propped behind the bar in a grubby apron (bloodstains?) cleaning a dirty mug with a dirtier rag. Mia noticed one of his eyes moved slightly before the other, like a child leading a slow cousin by the hand.

‘Good turning to you, sir,’ she said, keeping her voice steady. ‘Aa bless and keep you.’

‘Come in wiv Wolfeater’s mob, didjer?’

‘Well spotted, sir.’

‘Pay’s four beggars weekly, but yer get board onna top.fn6 Twenty per cent of anyfing you make turning trick onna side comes to me direct. And I’ll need a sample a’fore yer hired. Fair?’

Mia’s smile dragged the proprietor’s behind the bar and quietly strangled it.

It made very little sound as it died.

‘I’m afraid you misunderstand, sir,’ she said. ‘I am not here to apply for employ within your’ – a glance about her – ‘no doubt fine establishment.’

A sniff. ‘Whya ’ere then?’

She placed the sheepskin purse atop the bar. The treasure within clinked with a tune nothing like gold. If you were in the business of dentistry, you might have recognised that the tiny orchestra inside the bag was comprised entirely of human teeth.

It took her a moment to speak. To find the words she’d practised until she dreamed them.

‘My tithe for the Maw.’

The man looked at her, expression unreadable. Mia tried to keep the tremors from her breath, her hands. Six years it had taken her to come this far. Six years of rooftops and alleys and sleepless nevernights. Of dusty tomes and bleeding fingers and noxious gloom. But at last, she stood on the threshold, a small nod away from the vaunted halls of the Red—

‘What’s me maw got tado wivvit?’ the proprietor blinked.

Mia kept her face as stone, despite the dreadful flips her insides were undertaking. She glanced around the room. The tomb-raiders were bent over their map. A handful of local wags were playing ‘spank’ with a pack of mouldy cards. A woman in desert-coloured robes and a veil was drawing spiral patterns on a tabletop with what looked like blood.

‘The Maw,’ Mia repeated. ‘This is my tithe.’

‘Maw’s dead,’ the barman frowned.

‘… What?’

‘Been dead nigh on four truedarks now.’

‘The Maw,’ she scowled. ‘Dead. Are you mad?’

‘You’re the one bringing my old dead mum presents, lass.’

Realization tapped her on the shoulder, danced a funny little jig.

Ta-da.

‘I’m not talking about your mother, you fucki—’

Mia caught her temper by the collar, gave it a good hard shake. Clearing her throat, she brushed her crooked fringe from her eyes.

‘I do not refer to your mother, sir. I mean the Maw. Niah. The Goddess of Night. Our Lady of Blessed Murder. Sisterwife to Aa, and mother to the hungry Dark within us all.’

‘O, you mean the Maw.’

‘Yes.’ The word was a rock, hurled right between the barman’s eyes. ‘The Maw.’

‘Sorry,’ the man said sheepishly. ‘It’s just the accent, y’know.’

Mia glared.

The barman cleared his throat. ‘There’s no church to the Maw ’round ’ere, lass. Worship of ’er kind’s outlawed, even onna fringe. Got no business wiv Muvvers of Night and someandsuch in this particular place of business. Bad for the grub.’

‘You are Fat Daniio, proprietor of the Old Imperial?’

‘I’m not fat—’

Mia slapped the bartop. Several of the spank players turned to stare.

‘But your name is Daniio?’ she hissed.

A pause. Brow creased in thought. The gaze of Daniio’s slow cousin eye seemed to be wandering off, as if distracted by pretty flowers, or perhaps a rainbow.fn7

‘Aye,’ Daniio finally said.

‘I was told – specifically told, mind you – to come to the Old Imperial on the coast of Ashkah and give Fat Daniio my tithe.’ Mia pushed the purse across the counter. ‘So take it.’

‘What’s in it?’

‘Trophy of a killer, killed in kind.’

‘Eh?’

‘The teeth of Augustus Scipio, high executioner of the Itreyan Senate.’

‘Is he comin’ ’ere to get them?’

Mia bit her lip. Closed her eyes.

‘… No.’

‘How the ’byss did he lose his—’

‘He didn’t lose them,’ Mia leaned farther forward, smell be damned. ‘I tore them out of his skull after I cut his miserable throat.’

Fat Daniio fell silent. An almost thoughtful expression crossed his face. He leaned in close, wreathed in the stench of rotten fish, tears springing unbidden to Mia’s eyes.

‘’Scuse me then, lass. But what am I s’posed to do with some dead tosser’s teeth?’