The Nevernight Chronicle

The door creaked open, and the Wolfeater ducked below the frame, stepping into the Old Imperial as if he owned a part share in it.fn8 A dozen crewmen followed, cramming into dingy booths and leaning against the creaking bar. With an apologetic shrug, Fat Daniio set to serving the Dweymeri sailors. Mia caught his sleeve as he headed towards the booths.

‘Do you have rooms here, sir?’

‘Aye, we do. One beggar a week, mornmeal extra.’

Mia pushed an iron coin into Fat Daniio’s paw.

‘Please let me know when that runs out.’

A week with no sign, no word, no whisper save the winds off the wastes.

The crew of Trelene’s Beau stayed aboard their ship while they resupplied, availing themselves of the town’s amenities frequently. A typical nevernight would commence with grub at the Old Imperial, a sally forth into the arms of Dona Amile and her ‘dancers’ at the appropriately named Seven Flavours,fn9 before returning to the Imperial for a session of liquor, song, and the occasional friendly knife fight. Only one finger was removed during the entirety of their stay. Its owner took its loss with good humour.

Mia sat in a gloomy corner with the hangman’s teeth pouched up on the wood before her. Eyes on the door every time it creaked. Eating the occasional bowl of astonishingly hot (and she had to admit, delicious) bowls of Fat Daniio’s ‘widowmaker’ chilli, her frown growing darker as the turning of the Beau’s departure drew ever closer.

Could Mercurio have been wrong? It’d been years since he’d sent an apprentice to the Red Church. Maybe the place had been swallowed by the wastes? Maybe the Luminatii had finally laid them to rest, as Justicus Remus had vowed to do after the Truedark Massacre?

And maybe this is all a test. To see if you’ll run like a frightened child …

She’d poke around the town at the turn of each nevernight, listening in doorways, almost invisible beneath her cloak of shadows. She came to know Last Hope’s residents all too well. The seer who augured for the town’s womenfolk, interpreting signs from a withered tome of Ashkahi script she couldn’t actually read. The slaveboy from Seven Flavours, plotting to murder his madam and flee into the wastes.

The Luminatii legionaries stationed in the garrison tower were the most miserable soldiers Mia had ever come across. Two dozen men at civilization’s end, a few sunsteel blades between them and the horrors of the Ashkahi Whisperwastes. The winds blowing off the old empire’s ruins were said to drive men mad, but Mia was sure boredom would do for the legionaries long before the whisperwinds did. They spoke constantly of home, of women, of whatever sins they’d committed to be stationed in the Republic’s arse-end.fn10 After a week, Mia was sick of all of them. And not a single one spoke a word of the Red Church.

Seven turns after she’d arrived in Last Hope, Mia sat watching the Beau’s crew seal their holds, their calls rough with grog. Part of her wanted little more than to skulk aboard as they put out to the blue. Run back home to Mercurio. But truth was, she’d come too far to give up now. If the Church expected her to tuck tail at the first obstacle, they knew her not at all.

Sitting atop the Old Imperial’s roof, she watched the Beau sail from the bay, a clove cigarillo at her lips. The whisperwinds rolled off the wastes behind her, shapeless as dreams. She glanced at the cat who wasn’t a cat, sitting in the long shadow the suns cast for her. Its voice was the kiss of velvet on a baby’s skin.

‘… you fear …’

‘That should please you.’

‘… mercurio would not have sent you here needlessly …’

‘The Luminatii have been trying to take down the Church for years. The Truedark Massacre changed the game.’

‘… if ill befell them, there would still be traces …’

‘You suggest we go out into the Whisperwastes and look?’

‘… that, wait here, or return home …’

‘None of those options hold much appeal.’

‘… fat daniio’s job offer still stands, i am sure …’

Her smile was thin and pale. She turned back to the sea, watching the sunslight glint and catch upon the gnashing waves. Dragging deep on her smoke and exhaling plumes of grey.

‘… mia …?’

‘Yes?’

‘… there is no need to be afraid …’

‘I’m not.’

A pause, filled with whispering wind.

‘… no need to lie, either …’

Mia ended up stealing most of her supplies.

Waterskins, rations, and a tent from Last Hope General Supplies and Fine Undertakers. Blankets, whisky, and candles from the Old Imperial. She’d already marked the finest stallion in the garrison stable for stealing, despite being as much at home in the saddle as a nun in a brothel.

She told herself the thievery would keep her sharp, and sneaking back into the robbed stores to deposit compensation on the countertops afterwards struck her as good sport.fn11 Seated at the Imperial’s hearth, she enjoyed a final bowl of widowmaker chilli and waited for the nevernight winds to begin, bringing blessed cool after a turn of red heat.

Mia glanced up as the front door creaked open, admitting curling fingers of dust.

The boy who entered looked Dweymeri – leviathan ink facial tattoos (of terrible quality), salt-kissed locks bound in matted knots. But his skin was olive rather than brown, and he was too short to be an islander; barely a head taller than Mia, truth told. Dressed in dark leathers, carrying a scimitar in a battered scabbard, smelling of horse and a long road. When he prowled into the room, he checked every corner with hazel eyes. As his stare roamed the alcoves, Mia pulled the shadows about herself, and faded like a watermark into the gloom.

The boy turned to Fat Daniio, polishing that same grubby cup with the same grubby cloth. Eyeing the man over, the boy spoke with a voice soft as velvet.

‘Blessings to you, sir.’

‘A’right,’ Fat Daniio replied. ‘What’ll you ’ave?’

‘I have this.’

The boy placed a small wooden box upon the counter. Mia’s eyes narrowed as it rattled. The boy looked around the room again, then spoke in a tight whisper.

‘My tithe. For the Maw.’fn12

CHAPTER 4

KINDNESS

Captain Puddles had loved his Mia.

He’d known her since he was a kitten, after all. Before he’d forgotten the warm press of his siblings around him, she’d cradled him in her arms and kissed him on his little pink nose and he’d known she’d always be the centre of his world.

And so when Justicus Remus had stooped to seize the girl’s wrist at his consul’s command, Captain Puddles spat a yellow-tooth hiss, reached out with a paw full of claws, and tore the justicus’s face from eyehole to lip. Roaring, the big man seized the brave captain’s head with one hand, his shoulders with the other, and with an almost practised ease, he twisted.

The sound was like wet sticks snapping, too loud to be drowned by Mia’s scream. And at the end of those dreadful damp pops, a black shape hung limp in the justicus’s hand; a warm, soft, purring shape Mia had fallen asleep beside every nevernight, now purring no more.

She lost herself then. Howling, clawing, scratching. Dimly aware of being seized by another Luminatii and slung over his shoulder. The justicus clutched his bleeding face and drew his sword, fire uncurling down its length, the steel glowing with painful, blinding light.

‘Not here, Remus,’ Scaeva said. ‘Your hands must be clean.’

The justicus bellowed at his men, and her mother had screamed and kicked. Mia called for her, but a sharp blow struck her head, and it was all she could do to not fall into the black beneath her feet as the Dona Corvere’s cries faded into nothing.

Servants’ stairs, spiralling down. A passageway through the Spine – not the wondrous halls of polished white gravebone and crystal chandeliers and marrowbornfn1 in all their finery. A dim and claustrophobic little tunnel, leading out into the grounds beyond. Mia had squinted up – the Ribs arching into storm-washed skies, the great council buildings and libraries and observatories – before the men threw her into an empty barrel, slammed the lid, and tossed it into a horse-drawn cart.

She felt the cart whipped into motion, the trundle of wheels across cobbles. Men rode in the tray beside her, but she couldn’t make out their words, stricken by the memory of Captain Puddles lying twisted on the floor, her mother in chains. She understood none of it. The barrel rasped against her skin, splinters plucking at her dress. She felt them cross bridge after bridge, the haze of semiconsciousness thin enough now for her to start crying, hiccupping and heaving. A fist slammed hard against the barrel’s flank.

‘Shut up, you little shit, or I’ll give you something to wail about.’

They’re going to kill me, she thought.

A chill stole over her. Not at the thought of dying, mind you; in truth, no child thinks of herself as anything less than immortal. The chill was a physical sensation, spilling from the darkness inside the barrel, coiling around her feet, cold as ice water. She felt a presence – or closer, a lack of one. Like the feeling of empty at an embrace’s end. And she knew, sure and certain, that something was in that barrel with her.

Watching her.

Waiting.

‘Hello?’ she whispered.

A ripple in the black. A silent, ink-spot earthquake. And where there had been nothing a moment before, something gleamed at her feet, caught by the tiny chinks of sunslight spilling through the barrel’s lid. Something long and wicked-sharp as only gravebone can be, its hilt crafted to resemble a crow in flight. Last seen skittering beneath the curtain as Consul Scaeva slapped her mother’s hand away and spoke of pleading and promises.

Dona Corvere’s gravebone stiletto.

Mia reached towards it. For the briefest moment, she swore she could see lights at her feet, glittering like diamonds in an ocean of nothing. She felt an emptiness so vast she thought she was falling – down, down into some hungry dark. And then her fingers closed on the dagger’s hilt and she clutched it tight, so cold it almost burned.

She felt the something in the dark around her.

The copper-tang of blood.

The pulsing rush of rage.

The cart bounced along the road, her stomach curdling until at last they drew to a halt. She felt the barrel lifted, slung, crashing to the ground with a bang that made her almost bite her tongue clean through. She heard voices again, loud enough to ken the words.

‘I’m sick to my guts on this, Alberius.’

‘Orders are orders. Luminus Invicta, aye?’ fn2

‘Sod off.’

‘You want to trifle with Remus? With Scaeva? The saviours of the bloody Republic?’

‘Saviours my arsehole. You ever wonder how they did it? Captured Corvere and Antonius right in the middle of an armed camp?’

‘No, I bloody don’t. Help me with this.’

‘I heard it was magiks. Black arkemy. Scaeva’s in truck—’

‘Get staunch, you bloody maid. Who cares how they did it? Corvere was a fucking traitor, and this is traitor’s get.’

The barrel lid was torn away. Mia squinted up at two men, dark cloaks thrown over white armour. The first was a man with arms like tree trunks and hands like dinner plates. The second had pretty blue eyes and the smile of a fellow who choked puppies for sport.

‘Maw’s teeth,’ breathed the first. ‘She can’t be more than ten.’

‘Never to see eleven.’ A shrug. ‘Hold still, girl. This won’t hurt long.’

The puppy-choker clutched Mia’s throat, drew a long, sharp knife from his belt. And there in the reflection on that polished steel, the little girl saw her death. It would’ve been easy then, to close her eyes and wait. She was ten years old, after all. Alone and helpless and afraid. But here is truth, gentlefriends, no matter the number of suns in your sky. At the heart of it, two kinds of people live in this world or any other: those who flee and those who fight. Your kind has many terms for the latter sort. Berserker. Killer instinct. More balls than brains.

And it shouldn’t surprise you, knowing what little you know already, that in the face of this thug and his blade, and laden with memory of her father’s execution

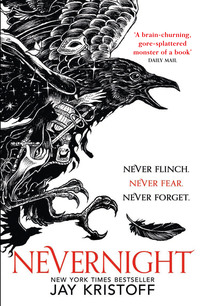

never flinch

never fear

instead of wailing or breaking as another ten-year-old might have, young Mia gripped the stiletto she’d fished from the darkness, and slipped it straight up into the puppy-choker’s eye.

The man screamed and fell backwards, blood gushing between his fingers. Mia rolled from the barrel, the sunslight impossibly bright after the darkness within. She felt the something come with her, coiled in her shadow, pushing at her heels. She saw they’d brought her to some mongrel bridge, a little canal choked with filth, boarded windows all around.

The dinner plate man’s eyes grew wide as his friend went down screaming. He drew a sunsteel sword and stepped towards the girl, flame rippling down its edge. But movement at his feet drew his eyes to the stone, and looking down, he saw the girl’s shadow begin to move. Clawing and twisting as if alive, reaching out towards him like hungry hands.

‘Light save me,’ he breathed.

The blade wavered in the thug’s grip. Mia backed away across the bridge, bloody knife in one trembling fist, the something still pressing at her heels. And as the puppy-choker clawed back to his feet with his face painted blood, the little girl did what anyone would have done in her position – ratio of balls to brains be damned.

‘… run …!’ said a tiny voice.

And run she did.

The Dweymeri boy underwent much the same exchange with Fat Daniio as Mia,fn3 although he suffered it with silent dignity.

The innkeeper informed him a girl had been asking the same questions, gestured to her booth – or at least, the booth she’d been sitting at. Mia had stolen up the stairwell by that point and was listening just out of sight, silent as an Itreyan Ironpriest.fn4

After muttering thanks, the Dweymeri boy asked if there were rooms available, paying coin from a malnourished purse. He was headed up the stairs when one of the local card players, a gent named Scupps, spoke.

‘Yer one of Wolfeater’s mob?’

The boy replied with a deep, soft voice. ‘I know no Wolfeater.’

‘He’s no crewman off the Beau.’ Mia recognised this second voice as Scupps’s brother, Lem. ‘Look at the size of ’im. He’s barely tall enough to reach Wolfeater’s balls.’

Laughter.

‘Mebbe that’s the point?’

More laughter.

The Dweymeri boy waited to ensure there was no more hilarity forthcoming, then continued up the stairs. Mia had slipped into her room, watching from the keyhole as the boy padded to his own door. His feet made barely a whisper, though Mia knew the boards squeaked like a family of murdered mice. The boy glanced over his shoulder towards her door, sniffed once, then slipped inside.

The girl sat in her room, considering whether to approach him or simply leave Last Hope at turn’s end as she planned.fn5 He was obviously looking for the same thing she was, but he was likely a cold-blooded psychopath. She doubted many novices seeking the Red Church had motives as altruistic as her own.

As soon as the town bells rang in nevernight, she heard the boy head downstairs, soft as velvet. She felt her shadow stir and stretch, insubstantial claws digging at the floorboards.

‘… if i do not return by the morrow, tell mother i love her …’

The girl snorted as the not-cat slipped beneath her door. She waited hours, reading by candlelight rather than open her shutters to the sun. If she was leaving this turn, she’d need do it at twelve bells, when the watchtower changed shifts. Easier to steal the stallion then. The knowledge she could have just bought some old nag raised its hand at the back of the lesson hall, and was shushed by the thought she shouldn’t be heading out into the wastes on anything but the finest horse this town had to offer.fn6

She felt a rippling chill, a sense of loss, and the cat who was shadows hopped up onto the bed beside her. Blinked with eyes that weren’t there. Tried to purr and failed.

‘Well?’

‘… he ate a sparing meal, watched the ones who insulted him between mouthfuls, and followed them home when they left …’

‘Did he kill them?’

‘… pissed in their water barrel …’

‘Not too bloodthirsty, then. And afterwards?’

‘… climbed up on the stable roof. he has been watching your window ever since …’

A nod. ‘I thought he marked me when he first entered.’

‘… a clever one …’

‘Let’s see how clever.’

Mia packed her things, books bound in a small oilskin satchel on her back. She’d hoped she might slip out unnoticed, but now this Dweymeri boy watched her, it was no longer a question of if she’d deal with him. Only how.

She snuck out from her room, across the squeaky floorboards, making no squeak at all. Sliding up to an empty room opposite, she slipped two lockpicks from a thin wallet, setting to work and hearing a small click a few minutes later. Slipping from the window, flitting across the roof, she felt sunslight burning the windblown sky, adrenaline tingling her fingertips. It was good to be moving again. Tested again.

Dashing across the alley between the Imperial and the bakery next door, boots less than a whisper on the road. The not-cat prowled in front, watching with his not-eyes.

Just as she’d done outside Augustus’s window, Mia reached out and took hold of the shadows about her. Thread by thread, she drew the darkness to her with clever fingers, like a seamstress weaving a cloak – a cloak over which unwary eyes might lose their way.

A cloak of shadows.

Call it what you will, gentlefriends. Thaumaturgy. Arkemy. Werking. Magik. Like all power, it comes with a tithe. As Mia pulled her shadows about her, the light grew dimmer in her eyes. As ever, it became harder for her to see past her veil of darkness, just as she was harder to see inside it. The world beyond was blurred, muddied, shrouded in black – she had to walk slow, lest she trip or stumble. But wrapped inside her shadows, she crept on, on through the nevernight glare, just a watercolour impression on the canvas of the world.

Up to the stable’s flank, climbing the downspout by feel. Crawling onto the roof, she squinted in her gloom, spotted the Dweymeri in the chimney’s shadow, watching her bedroom window. Mia padded across the tiles, imagining she was back in Old Mercurio’s warehouse; dead leaves scattered across the floor, a three-turn thirst burning in her throat, four wild dogs asleep around a decanter of crystal-clear water.

Motivation had been the old man’s watchword, sure and true.

Closer now. Uncertain whether to speak or act, begin or end. Perhaps twenty paces away, she saw the boy tense, turn his head. And then she was rolling beneath the fistful of knives he hurled, three in quick succession, gleaming in the light of that cursed sun. If this were truedark she would’ve had him. If this were truedark—

Don’t look.

She snapped to her feet, stiletto drawn, her shadow writhing across the tiles towards him. The Dweymeri boy had drawn his scimitar, two more throwing knives poised in his other hand. Dark saltlocks of matted hair swayed over his eyes. The tattoos on his face were the ugliest Mia had ever seen, looking like they’d been scrawled by a blind man in the midst of a seizure. Yet the face beneath …

The pair stood watching each other, still as statues, moments ticking by like hours as the gale howled about them.

‘You have very good ears, sir,’ she finally said.

‘You have better feet, Pale Daughter. I heard nothing.’

‘Then how?’

The boy offered a dimpled smile. ‘You stink of cigarillo smoke. Cloves, I think.’

‘That’s impossible. I’m upwind from you.’

The boy glanced at the shadows moving like snakes around his feet.

‘Seems to be raining impossible in these parts.’

She stared at him. Hard and sharp and lean and quick. A rapier in a world of broadswords. Mercurio was better at reading folk than any person she’d known, and he’d taught her to sum others up in a blinking. Whoever this boy was, whatever his reasons for seeking the Church, he was no psychopath. Not one who killed for killing’s sake.

Interesting.

‘You seek the Red Church,’ she said.

‘The fat man wouldn’t take my tithe.’

‘Nor mine. We’re being tested, I think.’

‘I thought the same.’

‘It’s possible they’re no longer here. I was heading into the wastes to look.’

‘If it’s death you seek, there are easier ways to find it.’ The boy gestured beyond Last Hope’s walls. ‘Where would you even start?’

‘I was planning on following my nose,’ Mia smiled. ‘But something tells me I’d do better following yours.’

The boy stared long and hard. Hazel eyes roaming her body, cool and narrowed. The blade in her hand. The shadows at his feet. The whispering wastes behind him.

‘My name is Tric,’ he said, sheathing the scimitar at his back.

‘… Tric? Are you certain?’

‘Certain about my own name? Aye, that I am.’

‘I mean no disrespect, sir,’ Mia said. ‘But if we’re to travell the Whisperwastes together, we should at least be honest enough to use our own names. And your name can’t be Tric.’

‘… Do you call me liar, girl?’

‘I called you nothing, sir. And I’ll thank you not to call me “girl” again, as if the word were kin to something you found on the bottom of your boot.’

‘You have a strange way of making friends, Pale Daughter.’

Mia sighed. Took her temper by the earlobe and pulled it to heel.

‘I’ve read the Dweymeri cleave to ritualised naming rites. Your names follow a set pattern. Noun then verb. Dweymeri have names like “Spinesmasher”. “Wolfeater”. “Pigfiddler”.’

‘… Pigfiddler?’

Mia blinked. ‘Pigfiddler was one of the most infamous Dweymeri pirates who ever lived. Surely you’ve heard of him?’

‘I was never one for history. What was he infamous for?’

‘Fiddling with pigs.fn7 He terrorised farmers from Stormwatch to Dawnspear for almost ten years. Had a three-hundred-iron bounty on him in the end. No hog was safe.’

‘… What happened to him?’

‘The Luminatii. Their swords did to his face what he did to the pigs.’

‘Ah.’

‘So. Your name cannot be Tric.’

The boy stared her up and down, expression clouded. But when he spoke, there was iron in his voice. Indignity. A well-nursed and lifelong anger.

‘My name,’ he said, ‘is Tric.’

The girl looked him over, dark eyes narrowed. A puzzle, this one. And sure and certain, our girl had ever the weakness for puzzles.

‘Mia,’ she finally said.

The boy walked slow and steady across the tiles, paying no attention to the black beneath him. Extending one hand. Calloused fingers, one silver ring – the long, serpentine forms of three seadrakes, intertwined – on his index finger. Mia looked the boy over, the scars and ugly facial tattoos, olive skin, lean and broad-shouldered. She licked her lips, tasted sweat.