Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's ships Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836

For want of better information upon the subject, we must be content to separate the natives into Patagonians and Fuegians. The sealing vessels' crews distinguish them as Horse Indians, and Canoe Indians.

These people have had considerable communication with the sealers who frequent this neighbourhood, bartering their guanaco skins and meat, their mantles, and furs, for beads, knives, brass ornaments, and other articles; but they are equally anxious to get sugar, flour, and, more than all, "aqua ardiente," or spirits. Upon the arrival of a boat from any vessel, Maria, with as many as she can persuade the boat's crew to take, goes on board, and, if permitted, passes the night. As soon as our boat landed, Maria and her friends took their seats as if it had been sent purposely for them. Not expecting such a visit, I had given no order to the contrary, and the novelty of such companions overcame the scruples of the officer, who was sent on shore to communicate with them. Their noisy behaviour becoming disagreeable, they were soon conducted from below to the deck, where they passed the night. Maria slept with her head on the windlass; and was so intoxicated, that the noise and concussion produced by veering eighty fathoms of cable round it did not awake her. The following morning, whilst I was at breakfast, she very unceremoniously introduced herself, with one of her companions, and seating herself at table, asked for tea and bread, and made a hearty meal. I took the precaution of having all the knives, and articles that I thought likely to be stolen, removed from the table; but neither then, nor at any time, did I detect Maria in trying to steal, although her companions never lost an opportunity of pilfering.

After breakfast the Indians were landed, and as many of the officers as could be spared went on shore, and passed the whole day with the tribe, during which a very active trade was carried on. There were about one hundred and twenty Indians collected together, with horses and dogs. It is probable that, with the exception of five or six individuals left to take care of the encampment, and such as were absent on hunting excursions, the whole of the tribe was mustered on the beach, each family in a separate knot, with all their riches displayed to the best advantage for sale.

I accompanied Maria to the shore. On landing, she conducted me to the place where her family were seated round their property. They consisted of Manuel, her husband, and three children, the eldest being known by the appellation of Capitan Chico, or "little chief." A skin being spread out for me to sit on, the family and the greater part of the tribe collected around. Maria then presented me with several mantles and skins, for which I gave in return a sword, remnants of red baize, knives, scissors, looking-glasses, and beads: of the latter I afterwards distributed bunches to all the children, a present which caused evident satisfaction to the mothers, many of whom also obtained a share. The receivers were selected by Maria, who directed me to the youngest children first, then to the elder ones, and lastly to the girls and women. It was curious and amusing, to witness the order with which this scene was conducted, and the remarkable patience of the children, who, with the greatest anxiety to possess their trinkets, neither opened their lips, nor held out a hand, until she pointed to them in succession.

Having told Maria that I had more things to dispose of for guanaco meat she dismissed the tribe from around me, and, saying she was going for meat (carne), mounted her horse, and rode off at a brisk pace. Upon her departure a most active trade commenced: at first, a mantle was purchased for a string of beads; but as the demand increased, so the Indians increased their price, till it rose to a knife, then to tobacco, then to a sword, at last nothing would satisfy them but 'aqua ardiente,' for which they asked repeatedly, saying "bueno es boracho – bueno es – bueno es boracho;"69– but I would not permit spirits to be brought on shore.

At Marians return with a very small quantity of guanaco meat, her husband told her that I had been very inquisitive about a red baize bundle, which he told me contained "Cristo," upon which she said to me "Quiere mirar mi Cristo" (do you wish to see my Christ), and then, upon my nodding assent, called around her a number of the tribe, who immediately obeyed her summons. Many of the women, however, remained to take care of their valuables. A ceremony then took place. Maria, who, by the lead she took in the proceedings, appeared to be high priestess70 as well as cacique of the tribe, began by pulverising some whitish earth in the hollow of her hand, and then taking a mouthful of water, spit from time to time upon it, until she had formed a sort of pigment, which she distributed to the rest, reserving only sufficient to mark her face, eyelids, arms, and hair with the figure of the cross. The manner in which this was done was peculiar. After rubbing the paint in her left hand smooth with the palm of the right, she scored marks across the paint, and again others at right angles, leaving the impression of as many crosses, which she stamped upon different parts of her body, rubbing the paint, and marking the crosses afresh, after every stamp was made.

The men, after having marked themselves in a similar manner (to do which some stripped to the waist and covered all their body with impressions), proceeded to do the same to the boys, who were not permitted to perform this part of the ceremony themselves. Manuel, Maria's husband, who seemed to be her chief assistant on the occasion, then took from the folds of the sacred wrapper an awl, and with it pierced either the arms or ears of all the party; each of whom presented in turn, pinched up between the finger and thumb, that portion of flesh which was to be perforated. The object evidently was to lose blood, and those from whom the blood flowed freely showed marks of satisfaction, while some whose wounds bled but little underwent the operation a second time.

When Manuel had finished, he gave the awl to Maria, who pierced his arm, and then, with great solemnity and care, muttering and talking to herself in Spanish (not two words of which could I catch, although I knelt down close to her and listened with the greatest attention), she removed two or three wrappers, and exposed to our view a small figure, carved in wood, representing a dead person, stretched out. After exposing the image, to which all paid the greatest attention, and contemplating it for some moments in silence, Maria began to descant upon the virtues of her Christ, telling us it had a good heart ('buen corazon'), and that it was very fond of tobacco. Mucho quiere mi Cristo tabaco, da me mas, (my Christ loves tobacco very much, give me some). Such an appeal, on such an occasion, I could not refuse; and after agreeing with her in praise of the figure, I said I would send on board for some. Having gained her point, she began to talk to herself for some minutes, during which she looked up, after repeating the words "muy bueno es mi Cristo, muy bueno corazon tiene," and slowly and solemnly packed up the figure, depositing it in the place whence it had been taken. This ceremony ended, the traffic, which had been suspended, recommenced with redoubled activity.

According to my promise, I sent on board for some tobacco, and my servant brought a larger quantity than I thought necessary for the occasion, which he injudiciously exposed to view. Maria, having seen the treasure, made up her mind to have the whole, and upon my selecting three or four pounds of it, and presenting them to her, looked very much disappointed, and grumbled forth her discontent: I taxed her with greediness, and spoke rather sharply, which had a good effect, for she went away and returned with a guanaco mantle, which she presented to me.

During this day's barter we procured guanaco meat, sufficient for two days' supply of all hands, for a few pounds of tobacco. It had been killed in the morning, and was brought on horseback cut up into large pieces, for each of which we had to bargain. Directly an animal is killed, it is skinned and cut up, or torn asunder, for the convenience of carrying. The operation is done in haste, and therefore the meat looks bad; but it is well tasted, excellent food, and although never fat, yields abundance of gravy, which compensates for its leanness. It improves very much by keeping, and proved to be valuable and wholesome meat.

Captain Stokes, and several of the officers, upon our first reaching the beach, had obtained horses, and rode to their 'toldos,' or principal encampment. On their return, I learned that, at a short distance from the dwellings, they had seen the tomb of the child who had lately died. As soon, therefore, as Maria returned, I procured a horse from her, and, accompanied by her husband and brother, the father of the deceased, and herself, visited these toldos, situated in a valley extending north and south between two ridges of hills, through which ran a stream, falling into the Strait within the Second Narrow, about a mile to the westward of Cape Gregory.

We found eight or ten huts arranged in a row; the sides and backs were covered with skins, but the fronts, which faced the east, were open; even these, however, were very much screened from wind by the ridge of hills eastward of the plain. Near them the ground was rather bare, but a little farther back there was a luxuriant growth of grass, affording rich and plentiful pasture for the horses, among which we observed several mares in foal, and colts feeding and frisking by the side of their dams: the scene was lively and pleasing, and, for the moment, reminded me of distant climes, and days gone by.

The 'toldos' are all alike. In form they are rectangular, about ten or twelve feet long, ten deep, seven feet high in front, and six feet in the rear. The frame of the building is formed by poles stuck in the ground, having forked tops to hold cross pieces, on which are laid poles for rafters, to support the covering, which is made of skins of animals sewn together so as to be almost impervious to rain or wind. The posts and rafters, which are not easily procured, are carried from place to place in all their travelling excursions. Having reached their bivouac, and marked out a place with due regard to shelter from the wind, they dig holes with an iron bar or piece of pointed hard wood, to receive the posts; and all the frame and cover being ready, it takes but a short time to erect a dwelling. Their goods and furniture are placed on horseback under the charge of the females, who are mounted aloft upon them. The men carry nothing but the lasso and bolas, to be ready for the capture of animals, or for defence.

Maria's toldo was nearly in the middle, and next to it was her brother's. All the huts seemed well stored with skins and provisions, the former being rolled up and placed at the back, and the latter suspended from the supporters of the roof; the greater part was in that state well known in South America by the name of charque (jerked beef); but this was principally horse-flesh, which these people esteem superior to other food. The fresh meat was almost all guanaco. The only vessels they use for carrying water are bladders, and sufficiently disagreeable substitutes for drinking utensils they make: the Fuegian basket, although sometimes dirty, is less offensive.

About two hundred yards from the village the tomb was erected, to which, while Maria was arranging her skins and mantles for sale, the father of the deceased conducted me and a few other officers.

It was a conical pile of dried twigs and branches of bushes, about ten feet high and twenty-five in circumference at the base, the whole bound round with thongs of hide, and the top covered with a piece of red cloth, ornamented with brass studs, and surmounted by two poles, bearing red flags and a string of bells, which, moved by the wind, kept up a continual tinkling.

A ditch, about two feet wide and one foot deep, was dug round the tomb, except at the entrance, which had been filled up with bushes. In front of this entrance stood the stuffed skins of two horses, recently killed, each placed upon four poles for legs. The horses' heads were ornamented with brass studs, similar to those on the top of the tomb; and on the outer margin of the ditch were six poles, each carrying two flags, one over the other.

The father, who wept much when he visited the tomb, with the party of officers who first went with him, although now evidently distressed, entered into, what we supposed to be, a long account of the illness of his child, and explained to us that her death was caused by a bad cough. No watch was kept over the tomb; but it was in sight of, and not very far from their toldos, so that the approach of any one could immediately be known. They evidently placed extreme confidence in us, and therefore it would have been as unjust as impolitic to attempt an examination of its contents, or to ascertain what had been done with the body.

The Patagonian women are treated far more kindly by their husbands than the Fuegian; who are little better than slaves, subject to be beaten, and obliged to perform all the laborious offices of the family. The Patagonian females sit at home, grinding paint, drying and stretching skins, making and painting mantles. In travelling, however, they have the baggage and provisions in their charge, and, of course, their children. These women probably have employments of a more laborious nature than what we saw; but they cannot be compared with those of the Fuegians, who, excepting in the fight and chace, do every thing. They paddle the canoes, dive for shells and sea-eggs, build their wigwams, and keep up the fire; and if they neglect any of these duties, or incur the displeasure of their husbands in any way, they are struck or kicked most severely. Byron, in his narrative of the loss of the Wager, describes the brutal conduct of one of these Indians, who actually killed his child for a most trifling offence. The Patagonians are devotedly attached to their offspring. In infancy they are carried behind the saddle of the mother, within a sort of cradle, in which they are securely fixed. The cradle is made of wicker-work, about four feet long and one foot wide, roofed over with twigs like the frame of a tilted waggon. The child is swaddled up in skins, with the fur inwards or outwards according to the weather. At night, or when it rains, the cradle is covered with a skin that effectually keeps out the cold or rain. Seeing one of these cradles near a woman, I began to make a sketch of it, upon which the mother called the father, who watched me most attentively, and held the cradle in the position which I considered most advantageous for my sketch. The completion of the drawing gave them both great pleasure, and during the afternoon the father reminded me repeatedly of having painted his child ("pintado su hijo.")

One circumstance deserves to be noticed, as a proof of their good feeling towards us. It will be recollected that three Indians, of the party with whom we first communicated, accompanied us as far as Cape Negro, where they landed. Upon our arrival on this occasion, I was met, on landing, by one of them, who asked for my son, to whom they had taken a great fancy; upon my saying he was on board, the native presented me with a bunch of nine ostrich feathers, and then gave a similar present to every one in the boat. He still carried a large quantity under his arm, tied up in bunches, containing nine feathers in each; and soon afterwards, when a boat from the Beagle landed with Captain Stokes and others, he went to meet them; but finding strangers, he withdrew without making them any present.

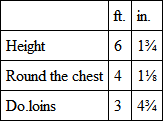

In the evening my son landed, when the same Indian came down to meet him, appeared delighted to see him, and presented him with a bunch of feathers, of the same size as those which he had distributed in the morning. At this, our second visit, there were about fifty Patagonian men assembled, not one of whom looked more than fifty-five years of age. They were generally between five feet ten and six feet in height: one man only exceeded six feet – whose dimensions, measured by Captain Stokes, were as follows: —

I had before remarked the disproportionate largeness of head, and length of body of these people, as compared with the diminutive size of their extremities; and, on this visit, my opinion was further confirmed, for such appeared to be the general character of the whole tribe; and to this, perhaps, may be attributed the mistakes of some former navigators. Magalhaens, or rather Pigafetta, was the first who described the inhabitants of the southern extremity of America as giants. He met some at Port San Julian, of whom one is described to be "so tall, that our heads scarcely came up to his waist, and his voice was like that of a bull." Herrera,71 however, gives a less extravagant account of them: he says, "the least of the men was larger and taller than the stoutest man of Castile;" and Maxim. Transylvanus says they were "in height ten palms or spans; or seven feet six inches."

In Loyasa's voyage (1526), Herrera mentions an interview with the natives, who came in two canoes, "the sides of which were formed of the ribs of whales." The people in them were of large size "some called them giants; but there is so little conformity between the accounts given concerning them, that I shall be silent on the subject."72

As Loyasa's voyage was undertaken immediately after the return of Magalhaens' expedition, it is probable that, from the impressions received from Pigafetta's narrative, many thought the Indians whom they met must be giants, whilst others, not finding them so large as they expected, spoke more cautiously on the subject; but the people seen by them must have been Fuegians, and not those whom we now recognise by the name of Patagonians.

Sir Francis Drake's fleet put into Port San Julian, where they found natives 'of large stature;' and the author of the 'World Encompassed,' in which the above voyage is detailed, speaking of their size and height, supposes the name given them to have been Pentagones, to denote a stature of "five cubits, viz. seven feet and a half," and remarks that it described the full height, if not somewhat more, of the tallest of them.73 They spoke of the Indians whom they met within the Strait as small in stature.74

The next navigator who passed through the Strait was Sarmiento; whose narrative says little in proof of the very superior size of the Patagonians. He merely calls them "Gente Grande,"75 and "los Gigantes;" but this might have originated from the account of Magalhaens' voyage. He particularises but one Indian, whom they made prisoner, and only says "his limbs are of large size: " ("Es crecido de miembros.") This man was a native of the land near Cape Monmouth, and, therefore, a Fuegian. Sarmiento was afterwards in the neighbourhood of Gregory Bay, and had an encounter with the Indians, in which he and others were wounded; but he does not speak of them as being unusually tall.

After the establishment, called 'Jesus,' was formed by Sarmiento, in the very spot where 'giants' had been seen, no people of large stature are mentioned, in the account of the colony; but Tomé Hernandez, when examined before the Vice-Roy of Peru, stated, "that the Indians of the plains, who are giants, communicate with the natives of Tierra del Fuego, who are like them."76

Anthony Knyvet's account77 of Cavendish's second voyage (which is contained in Purchas), is not considered credible. He describes the Patagonians to be fifteen or sixteen spans in height; and that of these cannibals, there came to them at one time above a thousand! The Indians at Port Famine, in the same narrative, are mentioned as a kind of strange cannibals, short of body, not above five or six spans high, very strong, and thick made.78

The natives, who were so inhumanly murdered by Oliver Van Noort, on the Island of Santa Maria (near Elizabeth Island), were described to be nearly of the same stature as the common people in Holland, and were remarked to be broad and high-chested. Some captives were taken on board, and one, a boy, informed the crew that there was a tribe living farther in-land, named 'Tiremenen,' and their territory 'Coin;' that they were "great people, like giants, being from ten to twelve feet high, and that they came to make war against the other tribes,79 whom they reproached for being eaters of ostriches!"80

Spilbergen (1615) says he "saw a man of extraordinary stature, who kept on the higher grounds to observe the ships;" and on an island, near the entrance of the Strait, were found the dead bodies of two natives, wrapped in the skins of penguins, and very lightly covered with earth; one of them was of the common human stature, the other, the journal says, was two feet and a half longer.81 The gigantic appearance of the man on the hills may perhaps be explained by the optical deception we ourselves experienced.

Le Maire and Schouten, whose accounts of the graves of the Patagonians agree precisely with what we noticed at Sea Bear Bay, of the body being laid on the ground covered with a heap of stones, describe the skeletons as measuring ten or eleven feet in length, "the skulls of which we could put on our heads in the manner of helmets!"

The Nodales did not see any people on the northern side of the Strait; those with whom they communicated were natives of Tierra del Fuego, of whose form no particular notice is taken.

Sir John Narborough saw Indians at Port San Julian, and describes them as "people of a middling stature: well-shaped. … Mr. Wood was taller than any of them." He also had an interview with nineteen natives upon Elizabeth Island, but they were Fuegians.

In the year 1741, Patagonian Indians were seen by Bulkley and his companions. They were mounted on horses, or mules, which is the first notice we have of their possessing those animals.

Duclos de Guyot, in the year 1766, had an interview with seven Patagonian Indians, who were mounted on horses equipped with saddles, bridles, and stirrups. The shortest of the men measured five feet eleven inches and a quarter English. The others were considerably taller. Their chief or leader they called 'Capitan.'

Bougainville, in 1767, landed amongst the Patagonians. Of their size he remarks: "They have a fine shape; among those whom we saw, not one was below five feet ten inches and a quarter (English), nor above six feet two inches and a half in height. Their gigantic appearance arises from their prodigiously broad shoulders, the size of their heads, and the thickness of all their limbs. They are robust and well fed: their nerves are braced and their muscles strong, and sufficiently hard, &c." This is an excellent account; but how different is that of Commodore Byron, who says, "One of them, who afterwards appeared to be chief, came towards me; he was of gigantic stature, and seemed to realise the tales of monsters in a human shape: he had the skin of some wild beast thrown over his shoulders, as a Scotch Highlander wears his plaid, and was painted so as to make the most hideous appearance I ever beheld: round one eye was a large circle of white, a circle of black surrounded the other, and the rest of his body was streaked with paint of different colours. I did not measure him; but if I may judge of his height by the proportion of his stature to my own, it could not be less than seven feet. When this frightful colossus came up, we muttered somewhat to each other as a salutation, &c."82 After this he mentions a woman "of most enormous size;" and again, when Mr. Cumming, the lieutenant, joined him, the commodore says, "Before the song was finished, Mr. Cumming came up with the tobacco, and I could not but smile at the astonishment which I saw expressed in his countenance upon perceiving himself, though six feet two inches high, become at once a pigmy among giants, for these people may, indeed, more properly be called giants than tall men: of the few among us who are full six feet high, scarcely any are broad and muscular, in proportion to their stature, but look rather like men of the common bulk grown up accidentally to an unusual height; and a man who should measure only six feet two inches, and equally exceed a stout well-set man of the common stature in breadth and muscle, would strike us rather as being of a gigantic race, than as an individual accidentally anomalous; our sensations, therefore, upon seeing five hundred people, the shortest of whom were at least four inches taller, and bulky in proportion, may be easily imagined."83