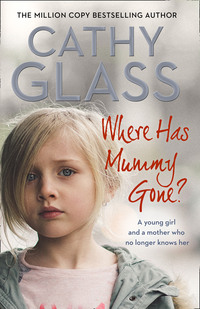

Where Has Mummy Gone?

Copyright

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2018

FIRST EDITION

Text © Cathy Glass 2018

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photograph © Kristina Dominianni/Arcangel Images (posed by a model)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008305468

Ebook Edition © September 2018 ISBN: 9780008305475

Version 2018-07-31

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Chapter One: Familiar?

Chapter Two: Safe and Happy

Chapter Three: Mummy Needs Me

Chapter Four: School

Chapter Five: Amanda

Chapter Six: The Way Home?

Chapter Seven: Lost

Chapter Eight: Difficult

Chapter Nine: When Can I See Mummy?

Chapter Ten: Snow Angel

Chapter Eleven: Review

Chapter Twelve: Four Sleeps

Chapter Thirteen: Heartbreaking

Chapter Fourteen: Precious Freedom

Chapter Fifteen: Staying Positive

Chapter Sixteen: Amanda – a Mother

Chapter Seventeen: Not Thursday

Chapter Eighteen: Developments

Chapter Nineteen: Caught His Plane

Chapter Twenty: A Timely Reminder

Chapter Twenty-One: Match

Chapter Twenty-Two: Coping?

Chapter Twenty-Three: Robbed of Dignity

Chapter Twenty-Four: True Heroes

Chapter Twenty-Five: Introductions

Chapter Twenty-Six: Overtired and Emotional

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Lucky to Have Her

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Family

Suggested topics for reading-group discussion

Cathy Glass

If you loved this book …

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Praise for Cathy Glass

About the Publisher

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to my family; my editors, Carolyn and Holly; my literary agent, Andrew; my UK publishers HarperCollins, and my overseas publishers, who are now too numerous to list by name. Last, but definitely not least, a big thank you to my readers for your unfailing support and kind words. They are much appreciated.

Chapter One

Familiar?

I was sure I’d heard it all before …

The child I was being asked to foster had been badly neglected for years by her single mother, who was an intravenous drug user and alcohol dependent. The social services were going to court later that morning to bring the child into care. Melody was eight years of age and had been sleeping on an old stained mattress on the floor of a damp, cold basement flat with her mother, and they were about to be evicted. She hadn’t been attending school, and despite the social services putting in support, there was never any food in the cupboards and she and her mother were often hungry, cold and dirty.

‘She is also very angry,’ Jill, my supervising social worker from the agency I fostered for, continued over the phone. The referral from the social services had come through her.

‘The mother is angry?’ I asked.

‘Yes, and Melody – her child – is too. She tried to kick and thump the social worker when she visited yesterday and threw something at her when she began talking to her mother. The social worker will take a police officer with her when she removes Melody, assuming the care order is granted.’

‘Is there any doubt?’

‘There shouldn’t be, but you never can tell. It will depend on the judge. The case is in court shortly, so it’s likely to be early afternoon before they are with you.’

‘All right.’ Forcibly removing a child from their home wasn’t a good start, but if the parent wasn’t cooperating there was no alternative. The mother had been given plenty of opportunities to sort out her life and parent her daughter properly but had repeatedly failed.

‘Amanda, the mother, can’t control Melody,’ Jill said. ‘She’s failed to put in place any boundaries and Melody can easily become angry. One social worker described her as feral.’

One of the reasons I had been asked to foster Melody was because I had years of fostering experience, much of it working with children with challenging behaviour, and I knew why Melody was angry. Even though she had been living in appalling conditions and had not been looked after, she was being taken away from the mother she knew and loved.

‘She’s very loyal and protective of her mother,’ Jill continued, ‘and won’t hear any criticism of her. They both hate social workers. Melody does as she likes and is very much the one in control.’ Again, this wasn’t unusual for a child who’d had to raise herself.

‘And her father?’ I asked. Knowledge of the family helps the foster carer.

‘They don’t live together. It’s unclear if Melody sees him at all. He’s also an intravenous drug user. Both parents have served prison sentences for drug dealing.’ Which again I’d heard before. ‘Melody has four older half-siblings, different fathers. All those children were taken into care and then adopted years ago.’

‘Why leave it so long to bring Melody into care?’ I asked, almost sure of the answer.

‘Her mother, Amanda, is very good at evading the social services,’ Jill said. ‘She has been moving flats regularly and doesn’t answer the door when a social worker visits, or she gets someone else to say they don’t live there. The social worker only got access yesterday because the main door was open. It’s a multiple-occupancy house and their room is in the basement. The room was freezing, and Melody and her mother were watching television in bed with their coats on.’

‘Dear me,’ I sighed.

‘Amanda has been funding her drug habit from prostitution. If she’s brought the clients back to her room, there is a possibility Melody has witnessed her mother with them, and might even have been sexually abused herself. So be vigilant for any disclosures she may make. Oh yes, and she has nits,’ Jill added. This was common for children coming into care.

‘I assume Melody won’t be returning home?’

‘Highly unlikely. The social services intend to apply for a Full Care Order, so she will remain in care.’ Sad though this was, in cases like these there really was no alternative. It was too early to say if Melody would have the chance of being adopted, but aged eight and with behavioural problems it was unlikely.

‘So, Cathy,’ Jill said, rounding off, ‘that’s it really. Neave, the social worker, will phone once she’s left court, then she and a colleague will take a police officer to collect Melody from home and come to you. I’ll try to be with you when she is placed.’

‘Thank you.’ Jill, as my supervising social worker, offered support and made sure I had all the information I needed and the correct placement forms were signed when a child was placed.

‘See you later then,’ she said, and we said goodbye.

Yes, it was a depressingly familiar story, which I was sure I’d heard before about many children brought into care. As it turned out, I couldn’t have been more wrong. There was another side to Melody’s story, which at this point no one knew.

Chapter Two

Safe and Happy

Even after many years of fostering I’m still slightly anxious before a new child arrives, wondering if they will like us and what I will be able to do to help them. Now I had the added concern of Melody’s angry and challenging behaviour. But by lunchtime I’d given her bedroom a final check, cleaned, hoovered and tidied all the communal areas in the house (I might not have another chance for a while), then I tried to concentrate on the part-time administration work I did mainly from home. As a single parent – my husband having run off with another woman some years before – the admin work plus the small allowance I received from fostering helped to make ends meet. I’d have fostered anyway, even without the allowance. I enjoyed it, and it had become a way of life.

My three children – Adrian, aged sixteen, Lucy, fourteen, and Paula, twelve – were at school, so they’d have a surprise when they arrived home to find Melody here, although it wouldn’t be a huge one. Adrian and Paula had grown up with fostering and knew children could arrive at very short notice. Lucy had been in foster care herself before I’d adopted her, so was only too familiar with the way the system worked. (I tell Lucy’s story in my book Will You Love Me?)

I had a sandwich lunch as I worked and it was nearly two o’clock before the front doorbell rang, signalling Melody’s arrival. I felt my pulse step up a beat as I left the paperwork on the table in the front room and went to answer the door. A female social worker I took to be Neave stood on one side of Melody and a male social worker was on the other, as if escorting her.

‘Hello, you must be Melody,’ I said with a smile. ‘Come in. I’m Cathy.’

Melody glared at me but didn’t move. ‘This is the foster carer I told you about,’ Neave said, and touched Melody’s arm to encourage her to move forward.

‘Get your hands off me!’ Melody snapped, angrily shrugging her off, but she did come in.

‘I’m Neave, and this is my colleague Jim,’ Neave said as they too came in.

Jim shook my hand. I guessed both social workers were in their early forties, and were dressed smartly in dark colours, having come straight from court.

‘Shall I take your coats?’ I offered, but Neave was already halfway down the hall, looking to see which room she should go in. ‘Straight ahead!’ I called. Jim took off his coat and also his shoes, which he paired with ours beneath the hall stand.

‘Would you like to take off your coat and shoes?’ I asked Melody, who was still standing beside us and hadn’t followed her social worker into the living room. She looked at me as though I was completely barmy, probably having never taken off her shoes and coat as part of the routine for entering her home. ‘We usually do,’ I added.

Melody was of average height and build, but her pale skin was grubby. There were dark rings under her eyes from lack of sleep and her brown, shoulder-length hair was unwashed and matted. I already knew she had nits and I would treat those later. Her zip-up anorak was filthy, a long rip down one sleeve showed the white lining and the zipper was undone and hanging off. Beneath her jacket she was wearing a badly stained jumper and short skirt. The skirt and ankle socks she wore were more suitable for summer than winter; her legs must have been freezing. Her filthy plastic trainers had holes in the ends where her toes poked through. Not for the first time since I’d started fostering, I felt greatly saddened that in our reasonably affluent society a child could still appear in this state.

‘Are you going to take off your coat and shoes?’ Jim now asked.

‘No!’ Melody said, and headed down the hall.

‘That told us,’ I said quietly to Jim. He smiled. Foster carers and social workers have to maintain a sense of humour in order to survive the suffering and sadness we see each day. I’d ease Melody into our way of doing things as we went along.

‘Would anyone like a drink?’ I asked as Jim and I entered the living room.

‘Coffee, please,’ Neave said from the sofa. ‘Milk, no sugar.’

‘And for me too, please, if it’s not too much trouble,’ Jim added.

‘And what about you?’ I asked Melody, who’d sat next to Neave.

‘No. I don’t want anything from you.’ She scowled.

‘OK, maybe later. There’s a box of games you might like to look at,’ I said, pointing to the toy box of age-appropriate games I’d put out ready. ‘There’s some children’s books on the shelves,’ I added.

‘Not looking,’ she said. Folding her arms defiantly across her chest, she glared at Neave. ‘I want to go home. Take me back, now!’

‘You know I can’t do that,’ Neave said. ‘I explained in the car what was happening.’

‘I don’t care what you said. It’s not your decision. It’s up to me and I want to go home!’

‘That’s not possible,’ Neave said evenly. ‘You’re staying with Cathy and her family for now, and she is going to look after you very well. You’ll do lots of nice things and you’ll see your mother soon.’

‘I want to see Mum now!’ Melody’s anger flared and for a moment I thought she was going to hit Neave. Neave thought so too, for she moved further up the sofa. ‘My mum needs me!’ Melody said with slightly less aggression. Many children come into care believing that their parents won’t be able to manage without them, and part of my role is to take away the inappropriate responsibility they’ve had at home and encourage them to be children.

I made my way towards the kitchen to make the coffee but as I left the living room the front doorbell rang. ‘That’ll be Jill,’ I said, and went to answer it.

‘Sorry I’m late,’ she said. ‘I’ve come straight from placing another child. Are they here?’

‘Yes, just arrived. They’re in the living room. I’m about to make coffee. Would you like one?’

‘Oh yes, please,’ she said gratefully. ‘Have you got a biscuit too? I haven’t had time for lunch.’

‘I could make you a sandwich?’ I offered.

‘No, a biscuit is fine.’

Jill went into the living room and introduced herself, while I set about making the coffee. I could hear Jill talking to Melody in a reassuring voice, telling her she would be happy with me, that I’d look after her and there was nothing for her to worry about. Jill was a highly experienced social worker and I greatly valued her input, support and advice.

I took the tray carrying the drinks and a plate of biscuits into the living room and set it on the coffee table. ‘Are you sure you wouldn’t like a drink?’ I asked Melody as I handed out the mugs of coffee.

‘No, but I’ll have a biscuit.’ Standing, she grabbed a handful of biscuits and returned to the sofa to eat them.

‘Are you hungry?’ Neave asked her as they quickly vanished.

‘No,’ she snarled.

‘I’ll make her something to keep her going until dinner once we’ve finished,’ I reassured Neave.

I passed the plate of biscuits to the adults and then put the empty plate on the tray. For a few moments there was quiet as they sipped their coffee and ate the biscuits. I thought Jill wasn’t the only one who hadn’t had time for lunch. Neave set her half-empty mug on the coffee table and took a wodge of papers from her briefcase. When a child is placed there are formalities that need to be completed, and Neave handed Jill and me a copy each of the Essential Information Form Part 1. This contained the basic information I needed about the child I was fostering, and I began to look through it, as did Jill, while Neave finished her coffee. Much of the information I already knew from Jill. It included Melody’s full name, most recent home address, date of birth and her parents’ names, and in the box for other family members was printed Four half-siblings, all adopted, but not their names. Melody’s ethnicity was given as white British and her first language English. The box for religion showed None, and her legal status showed Interim Care Order. There were no special dietary requirements and Melody had no known allergies. Her school’s name and address were shown with a comment in the box saying she’d only been there since September. It was January now, so she’d joined four months previously.

‘Melody changed school last term then?’ I asked Neave.

‘Yes, with the most recent move,’ she replied. ‘She’s had a lot of changes of school, with long gaps in between when she didn’t attend at all. Now she’s in care she’ll have more stability in her life. She’s very behind with her school work.’

‘I hate school. I’m not going,’ Melody said, her face setting.

‘All children have to go to school,’ Jill said gently.

‘I don’t!’ Melody snapped.

‘You do, love,’ I said. ‘All the children in this house go to school and tomorrow we’ll buy you a nice new school uniform.’ Not a bribe, but an incentive.

‘I was going to mention her clothing,’ Neave said. ‘I’m afraid she just has what she is wearing. Her mother said she has other clothes, but they needed washing.’

‘Not a problem,’ I said. ‘We’ll use my emergency supply until we can go shopping and buy her new clothes. The school usually sells the uniform, so we can get that tomorrow morning when we go in.’

‘That’ll be nice, won’t it?’ Jill said encouragingly, turning to Melody. ‘Lots of new clothes.’

Melody scowled, but not quite so forcibly. All children like new things, especially when they haven’t had any before.

Jill and I returned to the Essential Information Form. The next line was about special educational needs – Melody requires classroom support was printed in the box. The next question asked if the child had any challenging behaviour and printed in the box was Melody has challenging behaviour. She can be angry. The next box about contact arrangements was empty.

‘Contact?’ Jill queried.

‘I’ll confirm the contact arrangements when I’ve spoken to the Family Centre to check availability,’ Neave said. ‘Melody will have supervised contact with her mother at the Family Centre – I’m anticipating on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, four till five-thirty. You’ll be able to take and collect her?’ Neave asked me. It’s expected that foster carers take children to and from contact, school and any appointments they may have.

‘Yes,’ I said, and made a note of the days and times in my diary.

‘I want to see my mum now!’ Melody demanded, having finished the biscuits.

‘You’ve just seen her,’ Neave said, ‘and you’ll see her again tomorrow – Wednesday.’

‘That’s not long,’ Jill said positively.

‘I want to see my mum at home!’

‘The Family Centre is like a home,’ I said. ‘It’s got sofas to sit on and lots of games to play with. I’ve taken children before and they always have a good time.’

Melody threw me a withering look and I returned my attention to the form, as did Jill.

‘Sibling contact with her half-brothers and sisters?’ Jill asked Neave.

‘No, there is no contact.’

‘And the care plan is long-term foster care then?’ Jill said.

‘Yes,’ Neave confirmed.

We had come to the end of the form and I placed my copy in my fostering folder.

‘I’ll need to arrange a LAC review,’ Neave now said. ‘I’ll let you know as soon as I have the details.’ LAC stands for ‘Looked After Child’, and all children in care have regular reviews to make sure everything is being done as it should to help them. The first review is usually held within the first four weeks of a child coming into care.

Toscha, our very old, docile and lovable cat sauntered out from behind the sofa where she’d been sleeping next to the radiator.

‘A cat!’ Melody cried in horror.

‘Don’t you like cats?’ Jim asked her.

‘No, they’re horrible. They have fleas that bite you.’ She began scratching her legs and I saw she had a lot of old insect bites.

‘Toscha doesn’t have fleas,’ I said.

‘My mum says all cats have fleas.’

‘I treat Toscha with flea drops so she doesn’t ever get them,’ I explained.

‘Do you have cats at home?’ Jill asked.

‘They come in when we open the door.’

‘There’s always a lot of stray cats around the entrance to the house and inside the communal hallway,’ Neave said. ‘I don’t expect anyone treats them.’

‘Try not to scratch,’ I said. ‘You’ll make them worse. I’ll put some antiseptic ointment on after your bath tonight.’

‘I don’t have baths,’ Melody said firmly. ‘It’s too cold.’ I’d heard similar before from other children I’d fostered who’d come from homes where they couldn’t afford heating and hot water.

‘It’s warm here,’ I reassured her. ‘The central heating is always on in winter and there’s plenty of hot water.’

Melody looked bewildered.

‘It’s bound to seem a bit strange at first,’ Jill said, ‘but Cathy is here to look after you. If you need anything or have any questions, ask her or one of her children. You’ll meet them later.’ Jill knew, as I did, that despite Melody’s bravado, as an eight-year-old child away from her mother, she must be feeling pretty scared and anxious.

‘Shall we look round the house now?’ Neave said to Jim. ‘Then we need to get back to the office.’

It’s usual for the foster carer to show the social worker and child around when they first arrive, so we all stood. I began with the room we were in, which looked out over the garden. ‘As you can see, we have some swings at the bottom of the garden,’ I said to Melody. ‘And there are bikes and other outdoor play things in the shed. You can play out there when the weather is good.’

‘And there are parks close by,’ Jill told her. ‘Cathy takes all the children she fosters to the park and other nice places, like the zoo and activity centres.’

Melody looked at us blankly. Giving her a reassuring smile, I led the way out of the living room and into our kitchen-cum-dining room. ‘This is where we eat,’ I said, pointing to the table. Toscha had followed us out and I saw Melody eyeing her carefully as she wandered over to her empty food bowl in a recess of the kitchen. ‘It’s not her dinner time yet,’ I said to Melody, trying to put her at ease.

‘Cats are always hungry,’ Jim added.

Melody looked suspiciously at Toscha and gave her leg another good scratch. ‘Honestly, love, she hasn’t got fleas,’ I said. I then led the way down the hall and into the front room. ‘This is a quiet room, if anyone wants to be alone,’ I explained. It held the computer, sound system, shelves of books, a cabinet with a lockable drawer where I kept important documents, and a small table and four chairs. It was sometimes used for homework and studying, and if anyone wanted their own space.