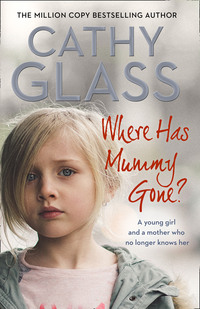

Where Has Mummy Gone?

‘Thank you,’ Neave said and we headed out.

We went upstairs, where I suggested we look at Melody’s room first. ‘It’s not my room,’ she said grumpily.

‘It’ll feel more comfortable once you have your things in here,’ I said as we entered. I told all the children this when I showed them round, for while the room was clean and tidy with a wardrobe, shelves, drawers and freshly laundered bed linen, it lacked any personalization that makes a room feel lived in and homely. Then I realized my mistake. Melody hadn’t come with any possessions. ‘Will her mother be sending some of her belongings?’ I now asked Neave and Jim.

‘There isn’t much,’ Neave replied. ‘They moved around so often that what they did have got ditched or left behind along the way. I’ll ask Amanda tomorrow.’

‘Have you got a special doll or teddy bear you would like from home?’ Jill asked Melody. A treasured item such as this helps a child to settle. Most children would have at least one favourite toy, but Melody just shrugged.

‘Perhaps one you sleep with?’ I suggested.

‘No, I sleep with my mum,’ she said. That Melody didn’t have one special toy was another indication of the very basic existence she’d lived with her mother. ‘I’ve got a ball,’ she added as an afterthought.

‘Would you like me to ask your mother for it?’ Neave asked her.

‘Don’t know where it is,’ she said disinterestedly, so I changed my approach.

‘You can choose some posters to put on the walls of your bedroom when we go shopping at the weekend,’ I said brightly. ‘And I’m sure I have a spare teddy bear here if you’d like one to keep you company.’ I always have a few handy.

‘Don’t mind,’ she said, which I took as a yes.

I showed them where the toilet and bathroom were, and then led them in and out of my children’s bedrooms, mentioning as we went that all our bedrooms, including Melody’s, were private, and that we didn’t go into each other’s rooms unless we were asked to, and we always knocked first.

‘That’s the same in a lot of homes,’ Jill told Melody, who was looking rather nonplussed. Having spent most of her life living in a single room with her mother in multi-occupancy houses, this was probably all very new to her.

Lastly, I opened the door to my bedroom so they could see in. ‘This is where I sleep,’ I told Melody. ‘If you need me during the night, call out and I’ll come to you.’

‘Do you leave a nightlight on in the landing?’ Neave asked.

‘Yes, and there’s a dimmer switch in Melody’s bedroom so we can set it to low if she wants a light on at night.’

We returned downstairs, where Neave confirmed she’d ask Melody’s mother to take any toys and clothes of Melody’s to contact tomorrow so they could be passed on to me, then she and Jim said goodbye and I saw them out. Jill stayed for another five minutes to make sure Melody had settled and then left. As soon as the front door closed, Melody asked, ‘When can I go home?’

‘What did Neave tell you?’ I asked gently.

‘That I had to live with you for now.’

‘That’s right. Try not to worry, you’ll see your mother tomorrow and again on Friday. Then every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. That’s three times a week.’ But what Neave wouldn’t have told Melody at this stage – and neither would I – was that, as it was likely she would be remaining in long-term care, the level of contact would gradually be reduced. Then at the end of the year when the final court hearing had been heard and the judge confirmed the social services’ care plan, Melody would probably see her mother only a couple of times a year for a few hours. Sad though this was, it was done to allow the child to bond with their carer and have a chance of a better life in the future. I should probably also say that when children come out of care at eighteen they invariably go back to their birth families – not always, but often.

‘I want to go home. My mum needs me,’ Melody said.

‘I understand, but try not to worry. Your mother is an adult and can look after herself, and Neave will make sure she’s all right.’

‘No, she won’t,’ Melody said.

Best keep Melody occupied, I thought. ‘Adrian, Lucy and Paula will be home from school in about half an hour,’ I said. ‘So we have time to treat your hair and give you a bath before I have to start making dinner.’

‘Treat my hair?’ she queried.

‘Yes, with nit lotion.’ I always kept a bottle in the bathroom cabinet, as so many children who come into care have head lice.

‘How do you know I have nits?’ Melody asked, seeming surprised I knew. ‘My mum said if I didn’t scratch no one would know.’

‘Your social worker told me,’ I said. ‘It must be very uncomfortable for you.’

‘It bleeding well is,’ she said, and jabbing both hands into her matted hair, she gave her scalp a good scratch. ‘Aah, that feels so much better!’ she sighed, relieved.

‘Good, but we don’t swear. Come on, let’s get the nit lotion on and you won’t have to scratch.’

‘Is not swearing another of your rules?’ she asked as she followed me upstairs. ‘Like knocking on bedroom doors.’

‘Yes, I suppose it is.’

‘Do you have many rules here?’

‘No, just a few to keep everyone safe and happy.’

‘I’ll tell my mum. She needs rules to make me safe and happy, then she can have me back.’

I smiled sadly, for of course it was far too late for that. Amanda had had her chance, and Melody wouldn’t be going back.

Chapter Three

Mummy Needs Me

‘I can smell nit lotion!’ my daughter Lucy cried from the hall as she let herself in the front door.

‘We’re in here!’ I called. I was in the kitchen peeling vegetables for dinner, and Melody was sitting at the table colouring in while the head-lice lotion took effect. I’d given her a bath – her first in months, she told me – and she was now dressed in clean clothes from the spares I kept. The lotion had a dreadfully pungent smell and needed to be left on for an hour, but I knew from using it on other children that it was very effective.

‘This is Melody,’ I said, introducing her to Lucy.

‘Hi, how are you? Don’t look so grumpy, you’ll be fine here.’ Having been neglected herself before coming to me as a foster child, Lucy could relate in a special way to the children we fostered. She had an easy manner with them and most of the children formed an attachment to her before they did me.

‘I’m not grumpy,’ Melody said. ‘I don’t like this stuff on my hair. My mum never put it on.’

‘That’s why you had head lice. That will kill the little buggers.’

‘Lucy,’ I admonished, ‘I’ve just told Melody not to swear.’

‘Ooops,’ Lucy said, and theatrically clamped her hand over her mouth. ‘Sorry.’ And for the first time I saw Melody smile. ‘Nice picture,’ Lucy said, going over and admiring Melody’s colouring in. Then to me she added, ‘I’m going to my room now, Mum.’

‘Fine, love. Did you have a good day at school?’

‘I guess.’

‘I want to go with you,’ Melody said, clearly finding Lucy’s company far more interesting than mine.

‘Not until the lotion is washed off. It’ll make my room smell.’

I glanced at the clock. ‘Only fifteen more minutes,’ I said.

‘That’s not fair,’ Melody moaned. ‘I want to go with you now.’

‘I’m flattered,’ Lucy said. ‘But you can’t until you’ve had your hair washed. See you later.’ Throwing her a smile, she left the room.

When I think back to how Lucy was when she first arrived, I feel so proud of all she’s achieved. I’m proud of Adrian and Paula too, of course, but Lucy had a shocking start to life and could so easily have gone off the rails. She had a lot of catching up to do, but she didn’t let her past hold her back. Her self-confidence has developed immeasurably; she is happy, has a good circle of friends, eats well and is achieving at school. I couldn’t love her more if she’d been born to me, and I feel very lucky that I have three wonderful children and am allowed to foster more.

No sooner had Lucy disappeared upstairs than Paula came home. She had a different nature to Lucy and was quieter, more placid and could easily let things worry her.

‘Hi, Paula,’ I called. ‘Come and meet Melody.’

‘Hello,’ Paula said, coming in.

‘Are you Lucy’s sister?’ Melody asked.

‘Yes.’

‘You got any more sisters?’

‘No.’ Paula smiled.

‘Good day?’ I asked her as I always ask my children when they first come home.

‘Yes, but I’ve got tons of homework. I’m going to start it now before dinner.’

‘OK, love. I’m nearly finished here, then I’ll wash Melody’s hair, so we’ll eat around six o’clock.’

Paula poured herself a glass of water and, giving Melody a small smile, left.

‘Where’s she gone?’ Melody asked.

‘In the front room to start her homework,’ I said.

‘Can I go?’

‘No, she needs quiet to concentrate. You will see her at dinner when we’ll all eat together.’ I put the chicken casserole in the oven. ‘Now, let’s wash your hair, then you can see Lucy.’

Melody didn’t object, probably because she knew she’d only spend time with Lucy once her hair was washed. We went to the bathroom where I thoroughly washed her hair. As I was rinsing it I heard my son Adrian arrive home. ‘Hi, Mum!’ he called from the hall. At sixteen, he was now six feet tall, although of course to me he’d always be my little boy.

‘I’m in the bathroom, washing Melody’s hair!’ I called down.

‘OK. I’ll say hi to her later.’ I heard him go through to the kitchen. When he came home from school he always fixed himself a drink and a snack to see him through to dinner.

‘You got any more kids?’ Melody asked, head over the bath as I continued to rinse her hair.

‘No, that’s it. Just the four of you.’

‘I’m not your kid,’ came her sharp retort.

‘OK, but while you’re living with me I’ll look after you as if you are.’ There was no reply.

With her hair thoroughly washed, rinsed and nit-free, I towel dried it and then brushed out the knots. She complained throughout that I was pulling, although I was as gentle as I could be. I then dried it with the hair dryer and it shone. It looked quite a few shades lighter now all the grease and grime had been removed. I don’t think it could have been washed for many months.

‘Can I go into Lucy’s room?’ Melody asked as soon as I’d finished.

‘Yes, but don’t forget to knock on her door first.’

She dashed around the landing and banged hard on Lucy’s door – not so much a knock, more a hammering.

‘Hell! Open the door. Don’t break it down!’ Lucy’s voice came from inside.

‘Can I come in?’ Melody yelled.

‘Yes! If you’ve had your hair washed.’

‘I have!’

She disappeared into Lucy’s room and that was the last I saw of her until I called everyone for dinner. Lucy knew that while Melody was with her she should leave her bedroom door open as part of our safer-caring policy, and to call me if there was a problem. All foster carers have a safer-caring policy and follow similar guidelines to keep all family members feeling safe. One of them is not to leave a foster child in a room with someone with the door closed. Leaving the door open means I and others can hear what is going on, and the child can come out easily whenever they want. There’s no knowing what a closed door might mean to an abused child, and Adrian knew that any girl we fostered wasn’t to go into his room at all, for his own protection. Sadly, many foster families have unfounded allegations made against them and they are very difficult to disprove.

Once dinner was ready I called everyone to the table and showed Melody where to sit. For us, it was a lively, chatty occasion as usual, when we shared our news as we ate. It’s often the only time we all sit down together during the week and it’s a pleasant focal point for us. Indeed, foster carers are expected to eat at least one meal a day together, as it bonds the family. At weekends we sometimes had breakfast together too. But Melody stared at us overawed as she ate.

Like many children who come from disadvantaged backgrounds, she wasn’t used to sitting at a table or using a knife and fork, having relied largely on snacks. She struggled to use the cutlery I’d set, so I quietly slipped her a dessertspoon to help with the casserole. She ate ravenously, all the while keeping a watchful eye on us. I’d seen the same vigilant awareness – a heightened state of alert – before in children I’d fostered who’d had to fend for themselves. They constantly watch those around them for any sign of danger. Children who’ve been nurtured and protected don’t do this, as experience has taught them that those they know can be trusted. It would take time for Melody to trust us.

I served rice pudding for dessert. It was a winter favourite of ours and despite Melody’s initial reluctance to try it, saying it looked like sick, she ate it all, and then asked for seconds. ‘Can I take some for my mum?’ she said as she finished the second bowl. ‘I think she’d like it.’ My heart went out to her.

‘Yes, I’ll put some in a plastic box and we can take it to contact tomorrow.’

‘Will it be cold?’ she asked.

‘Yes, but she can warm it up at the Family Centre. There’s a kitchen there with a cooker and a microwave.’

‘I’ll take her some of that casserole too,’ Melody added.

‘I’m afraid that’s all gone. Next time I make it I’ll do extra so she can have some. But please don’t worry about your mum. I’m sure she’ll have something to eat.’

Melody looked at me as if she was about to say something but changed her mind. Hopefully when she saw her mother she’d be reassured that she was managing without her.

After dinner, which I thought had gone well, Adrian, Paula and Lucy helped me clear the table, then disappeared off to do their homework. I was assuming that once Melody started going to school regularly she too would have some homework, but there wasn’t even a school bag tonight. I suggested we play a game together and I opened the toy cupboard in the kitchen-diner, but she said she wanted to watch television like she did at home with her mother. In the living room I switched the television channel to one with an age-appropriate programme, told her I’d be in the kitchen if she needed me and, taking the remote with me (so she couldn’t change channels to something less appropriate), set about doing the washing up. If my children have homework then they are excused from washing the dinner things.

First nights can be very difficult for a new child. Apart from suddenly finding themselves in a strange home and living with people they’ve only just met, the carer’s routine is likely to be very different from any the child has been used to. At 7.30, when the television programme Melody was watching had ended, I told her it was bedtime, which didn’t go down well. ‘What’s the time?’ she demanded, unable to read the time for herself.

‘Half past seven. Plenty late enough. You have school tomorrow.’ Indeed, it was only because she’d already had her bath and hair wash that she’d stayed up this late. Tomorrow she’d be going up around seven o’clock so that she was in bed and hopefully settled by eight o’clock. Children of her age need nine to eleven hours sleep a night.

‘At home I stay up with my mum. We go to sleep together. Sometimes she’s asleep before me.’

‘Is she?’ I asked lightly. ‘What do you do when she’s asleep?’ Clearly Melody wouldn’t be supervised if her mother was asleep.

‘Watch television. You can see the television from our mattress on the floor.’ She stopped, having realized she’d probably said too much. ‘Don’t tell the social worker I told you that.’

‘I think she already knows,’ I said. ‘Now, come on up to bed.’ I stood and began towards the living-room door. ‘You can say goodnight to Lucy, Adrian and Paula. They’re in their bedrooms.’

This seemed to clinch it and without further protest Melody came upstairs with me. I took her to the bathroom first, where I supervised her brushing her teeth with the new toothbrush and paste I’d provided. Like all foster carers, I keep spares of essential items. We went along the landing where Melody knocked first on Lucy’s bedroom door. ‘I’m going to bed!’ she called.

Lucy came out to say goodnight and gave Melody a big hug, which was nice. Then we went to Paula’s room. She too came out and said, ‘Goodnight. See you tomorrow.’ Then Adrian came to his door. ‘Goodnight. I hope you’ll be happy here,’ he said. Melody hadn’t seen much of him, only at dinner. He had exams in the spring, so it was important he studied. She’d see more of him at the weekend.

She used the toilet, then we went into her bedroom. I’d found a new teddy bear that Adrian had won at a fair and didn’t want, so I’d propped it on her bed. I asked her if she wanted her curtains open or closed at night and she said a little open. It’s details like this that help a child settle in a strange room, so I drew the curtains, leaving a gap in the middle. As I turned I saw she was about to climb into bed with her clothes on.

‘Melody, there are some pyjamas for you, love.’ I picked them up from where I’d left them on her bed. ‘You can wear these until we have time to buy you some new ones. They’re clean.’ I’d taken them from my selection of spares and was pretty sure they were the right size, as she was average build for an eight-year-old.

She paused and looked a bit confused. ‘I keep my clothes on at night at home because it’s so bleeding cold.’

‘Well, it’s not cold here, love, and remember we don’t swear.’

‘OK. It’s all so different here.’

‘I know, you’ll soon get used to it.’ But I was saddened to hear yet another example of the impoverished life Melody and her mother had led. No one should have to keep their clothes on to keep them warm at night.

I always give the child I’m fostering privacy whenever possible. Melody was of an age when she could dress and undress herself, so I waited on the landing while she changed into her pyjamas, as I had done when she’d had a bath. Once she was ready I went into her bedroom, thinking how nice it would be for her to climb into a comfortable, warm bed rather than the old mattress on a cold floor she’d been used to, but she didn’t get in. ‘I can’t go to bed here,’ she said anxiously. ‘My mum needs me.’

‘You’ll see her tomorrow,’ I reassured her. ‘Please try not to worry. She’ll be fine. I expect she’ll be going to bed soon too.’ Clearly I didn’t know what Melody’s mother was doing, but it wouldn’t help Melody to keep fretting about her.

‘She’s no good by herself,’ Melody said, still not getting in. ‘She needs me to tell her what to do.’

‘Melody, love, I know you’re missing your mother and she will be missing you, but she’s an adult. She can take care of herself.’

‘No, you don’t understand,’ Melody blurted, her anger and concern rising. ‘She forgets things. I have to be there to tell her what she needs and where things are.’

I paused. ‘Is that when she’s been drinking or taking drugs?’ I asked gently. Aware that her mother had a history of drug and alcohol abuse, this seemed the most likely explanation. Of course she would be ‘forgetful’ if she was under the influence of a substance.

‘Sometimes, but not always,’ Melody replied and then stopped, again realizing she’d probably said too much. Many children I’ve fostered have been warned by their parents not to disclose their home life to their foster carer or social worker. It can be very confusing for the child. Before saying anything, they have to sift through all the information they carry and work out what they can or can’t say. ‘Mum can remember some things, but other times she needs my help,’ Melody said carefully, and then she teared up.

‘Oh, love, don’t upset yourself. Come here.’ I put my arms around her and she allowed me to hold her close. ‘I do understand how you feel, honestly I do. I’ve looked after children before who’ve felt just as you do. They worry about their parents, and that they won’t be able to cope without them. Then, when they start seeing them regularly at contact, they find they’re managing fine without them. Your mother will be missing you, but believe me she can look after herself.’

How those words would come back to haunt me.

Chapter Four

School

Melody finally went to sleep shortly before nine o’clock, cuddling the teddy bear I’d given to her and with me sitting on her bed, stroking her forehead. Bless her. I felt so sorry for her. I was sure she was a good kid who was badly missing her mother. Yes, she was feisty, streetwise, could become angry at times and would need firm boundaries, but I felt positive that once she’d settled I could help her to a better life, which is what fostering is all about. Because it was unlikely Melody could return to her mother, the social services would try to find a suitable relative to look after her as the first option. They are called kinship carers and are considered the next best option if a child can’t be looked after by their own parents. If there wasn’t a suitable relative then she would be matched with a long-term foster carer, and if that happened it was possible I might be considered, but that was all in the future.

Once I was sure Melody was in a deep sleep, I moved quietly away from her bed and, turning the light down low, came out of her bedroom. I left the door ajar so I could easily hear her if she was restless in the night. I checked that Paula, Lucy and Adrian were taking turns in the bathroom. Even at their ages they still needed the occasional reminder to make sure they were in bed at a reasonable time. Some evenings, as with this evening, they were mostly in their bedrooms, doing their homework or relaxing, but at other times, especially at the weekends, they would all be downstairs in the living room, talking, playing a board game or watching television. I felt it was easier for a new child to relax and settle in if my family carried on as normal. I’d see them later before they went to bed, but now I went downstairs to write up my log notes.

All foster carers in the UK are required to keep a daily record of the child or children they are looking after. This includes appointments, the child’s health and wellbeing, education, significant events and any disclosures the child may make about their past. As well as charting the child’s progress, it can act as an aide-mémoire for the foster carer if asked about a specific day. When the child leaves, this record is placed on file at the social services. I wrote objectively and, where appropriate, verbatim about Melody’s arrival and her first day with us – about a page, which I secured in my fostering folder and returned to the lockable drawer in the front room.

I checked on Melody – she was fast asleep – and then as Adrian, Lucy and Paula came downstairs I spent some time talking to them before they went to bed. By 10.30 p.m. everyone was asleep and I put Toscha in her bed for the night and went up myself, again checking on Melody before I got into bed.

I never sleep well when there is a new child in the house. I’m half listening out in case they wake, frightened, not knowing where they are and in need of reassurance. But despite my restlessness and looking in on Melody three times, she slept very well, and I had to wake her at 7 a.m. to get ready for school.

‘Not going,’ she said as I opened her bedroom curtains to let in some light. ‘I need to go home and get my mum up.’

‘Melody, your mother will be able to get herself up, love. You’ll see her later at the Family Centre. Now get dressed, please. I want to go into school early today so I can buy you a new school uniform.’ She reluctantly clambered out of bed. ‘You can wear these for now,’ I said, handing her the fresh clothes I’d taken from my store.