Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age, Vol. 3 of 3

It should be easier for the English, than for the nations of most other countries, to make this picture real to their own minds; for it is the very picture before our own eyes in our own time and country, where visible traces of the patriarchal mould still coexist in the national institutions with political liberties of more recent fashion, because they retain their hold upon the general affections.

And, indeed, there is a sign, long posterior to the account given by Hesiod of the heroic age, and distinct also from the apparently favourable notice by Thucydides of the πατρικαὶ βασιλεῖαι, which might lead to the supposition that the old name of king left a good character behind it. It is the reverence which continued to attend that name, notwithstanding the evil association, which events could not fail to establish between it and the usurpations (τυραννίδες). For when the office of the βασιλεὺς had either wholly disappeared, as in Athens, or had undergone essential changes, as in Sparta, so that βασιλεία no longer appears with the philosophical analysts as one of the regular kinds of government, but μοναρχία is substituted, still the name remained58, and bore for long long ages the traces of its pristine dignity, like many another venerable symbol, with which we are loath to part, even after we have ceased either to respect the thing it signifies, or perhaps even to understand its significance.

Such is a rude outline of the history of the office. Let us now endeavour to trace the portrait of it which has been drawn in the Iliad of Homer.

Notes of Kingship in the Iliad.

1. The class of βασιλῆες has the epithet θεῖοι, which is never used by Homer except to place the subject of it in some special relation with deity; as for (a) kings, (b) bards, (c) the two protagonists, Achilles and Ulysses, (d) several of the heroes who predeceased the war, (e) the herald in Il. iv. 192; who, like an ambassador in modern times, personally represents the sovereign, and is therefore Διὸς ἄγγελος ἠδὲ καὶ ἀνδρῶν, Il. i. 334.

2. This class is marked by the exclusive application to it of the titular epithet Διοτρεφής; which, by the relations with Jupiter which it expresses, denotes the divine origin of sovereign power. The word Διογενὴς has a bearing similar to that of Διοτρεφὴς, but apparently rather less exclusive. Although at first sight this may seem singular, and we should perhaps expect the order of the two words to be reversed, it is really in keeping; for the gods had many reputed sons of whom they took no heed, and to be brought up under the care of Jupiter was therefore a far higher ascription, than merely to be born or descended from him.

3. To the βασιλεὺς, and to no one else, is it said that Jupiter has intrusted the sceptre, the symbol of authority, together with the prerogatives of justice59. The sceptre or staff was the emblem of regal power as a whole. Hence the account of the origin and successive deliveries of the sceptre of Agamemnon60. Hence Ulysses obtained the use of it in order to check the Greeks and bring them back to the assembly, ii. 186. Hence we constantly hear of the sceptre as carried by kings: hence the epithet σκηπτοῦχοι is applied to them exclusively in Homer, and the sceptre is carried by no other persons, except by judges, and by herald-serjeants, as their deputies.

4. The βασιλῆες are in many places spoken of as a class or order by themselves; and in this capacity they form the βουλὴ or council of the army. Thus when Achilles describes the distribution of prizes by Agamemnon to the principal persons of the army, he says61,

ἄλλα δ’ ἀριστήεσσι δίδου γέρα, καὶ βασιλεῦσιν.

In this place the Poet seems manifestly to distinguish between the class of kings and that of chiefs.

When he has occasion to speak of the higher order of chiefs who usually met in council, he calls them the γέροντες62, or the βασιλῆες63: but when he speaks of the leaders more at large, he calls them by other names, as at the commencement of the Catalogue, they are ἀρχοὶ, ἡγεμόνες, or κοίρανοι: and, again, ἀριστῆες64. In two places, indeed, he applies the phrase last-named to the members of that select class of chiefs who were also kings: but there the expression is ἀριστῆες Παναχαιῶν65, a phrase of which the effect is probably much the same as βασιλῆες Ἀχαιῶν: the meaning seems to be those who were chief over all orders of the Greeks, that is to say, chiefs even among chiefs. Thus Agamemnon would have been properly the only βασιλεὺς Παναχαιῶν.

The same distinction is marked in the proceedings of Ulysses, when he rallies the dispersed Assembly: for he addressed coaxingly, whatever king or leading man he chanced to overtake66.

ὅντινα μὲν βασιλῆα καὶ ἔξοχον ἄνδρα κιχείη,

5. The rank of the Greek βασιλεῖς is marked in the Catalogue by this trait; that no other person seems ever to be associated with them on an equal footing in the command of the force, even where it was such as to require subaltern commanders. Agamemnon, Menelaus, Nestor, Ulysses, the two Ajaxes, Achilles, are each named alone. Idomeneus is named alone as leader in opening the account of the Cretans, ii. 645, though, when he is named again, Meriones also appears (650, 1), which arrangement seems to point to him as only at most a quasi-colleague, and ὀπάων. Sthenelus and Euryalus are named after Diomed (563-6), but it is expressly added,

συμπάντων δ’ ἡγεῖτο βοὴν ἀγαθὸς Διομήδης.

Thus his higher rank is not obscured. Again, we know that, in the case of Achilles, there were five persons, each commanding ten of his fifty ships (Il. xvi. 171), of whom no notice is taken in the Catalogue (681-94), though it begins with a promise to enumerate all those who were in command of the fleet (493), and in the case of the Elians he names four leaders who had exactly the same command, each over ten ships (618). It thus appears natural to refer his silence about the five to the rank held by Achilles as a king.

ἀρχοὺς αὖ νηῶν ἐρέω νῆάς τε προπάσας;

So much for the notes of this class in the Iliad.

Though we are not bound to suppose, that Homer had so rigid a definition of the class of kings before his mind as exists in the case of the more modern forms of title, it is clear in very nearly every individual case of a Greek chieftain of the Iliad, whether he was a βασιλεὺς or not.

The Nine Greek Kings of the Iliad.

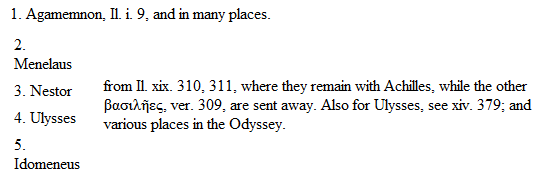

The class clearly comprehends:

6. Achilles, Il. i. 331. xvi. 211.

7. Diomed, Il. xiv. 27, compared with 29 and 379.

8. Ajax Telamonius, Il. vii. 321 connected with 344.

9. Ajax, son of Oileus.

Among the indications, by which the last-named chief is shown to have been a βασιλεὺς, are those which follow. He is summoned by Agamemnon (Il. ii. 404-6) among the γέροντες ἀριστῆες Παναχαιῶν: where all the abovenamed persons appear (except Achilles), and no others. Now the γέροντες or elders are summoned before in ver. 53 of the same book, and are called in ver. 86 the σκηπτοῦχοι βασιλῆες. Another proof of the rank of Oilean Ajax is the familiar manner in which his name is associated on terms of equality, throughout the poem, with that of Ajax Telamonius.

But the part of the poem, which supplies the most pointed testimony as a whole with respect to the composition of the class of kings, is the Tenth Book.

Here we begin with the meeting of Agamemnon and Menelaus (ver. 34). Next, Menelaus goes to call the greater Ajax and Idomeneus (53), and Agamemnon to call Nestor (54, 74). Nestor awakens Ulysses (137); and then Diomed (157), whom he sends to call Oilean Ajax, together with Meges (175). They then conjointly visit the φύλακες or watch, commanded by Thrasymedes, Meriones, and others (ix. 80. x. 57-9). Nestor gives the watch an exhortation to be on the alert, and then reenters within the trench, followed by the Argeian kings (194, 5);

τοὶ δ’ ἅμ’ ἕποντο

Ἀργείων βασιλῆες, ὅσοι κεκλήατο βουλήν.

The force of the term βασιλῆες, as marking off a certain class, is enhanced by the lines which follow, and which tell us that with them, the kings τοῖς δ’ ἅμα, went Meriones and Thrasymedes by special invitation (196, 7);

αὐτοὶ γὰρ κάλεον συμμητιάασθαι.

Now in this narrative it is not stated that each of the persons, who had been called, joined the company which visited the watch: but all who did join it are evidently βασιλῆες. But we are certain that Oilean Ajax was among them, because he is mentioned in ver. 228 as one of those in the Council, who were anxious to accompany Diomed on his enterprise.

Ajax Oileus therefore makes the ninth King on the Greek side in the Iliad.

These nine King-Chiefs, of course with the exception of Achilles, appear in every Council, and appear either absolutely or almost alone.

The line between them, and all the other chiefs, is on the whole preserved with great precision. There are, however, a very few persons, with regard to whom the question may possibly be raised whether they passed it.

Certain doubtful cases.

1. Meges, son of Phyleus, and commander of the Dulichian Epeans, was not in the first rank of warriors; for he was not one of the ten who, including Menelaus, were ready to accept Hector’s challenge67. Neither was he a member of the ordinary Council; but on one occasion, that of the Night-council, he is summoned. Those who attended on this occasion are also, as we have seen, called kings68. And we have seen that the term has no appearance of having been loosely used: since, after saying that the kings followed Nestor to the council, it adds, that with them went Meriones and Antilochus69.

But when Diomed proceeds to ask for a companion on his expedition, six persons are mentioned (227-32) as having been desirous to attend him. They are the two Ajaxes, Meriones, Thrasymedes, Menelaus, and Ulysses. Idomeneus and Nestor are of course excepted on account of age. It seems plain, however, that Homer’s intention was to include the whole company, with those exceptions only. He could not mean that one and one only of the able-bodied warriors present hung back. Yet Meges is not mentioned; the only one of the persons summoned, who is not accounted for. I therefore infer that Homer did not mean to represent him as having attended; and consequently he is in all likelihood not included among the βασιλῆες by v. 195.

2. Phœnix, the tutor and friend of Achilles, is caressingly called by him Διοτρεφὴς70 in the Ninth Book; but the petting and familiar character of the speech, and of the whole relation between them, would make it hazardous to build any thing upon this evidence.

In the Ninth Book it may appear probable that he was among the elders who took counsel with Agamemnon about the mission to Achilles, but it is not positively stated; and, even if it were, his relation to that great chieftain would account for his having appeared there on this occasion only (Il. ix. 168). It is remarkable that, at this single juncture, Homer tells us that Agamemnon collected not simply the γέροντες, but the γέροντες ἀολλέες, as if there were persons present, who did not belong to the ordinary Council (Il. ix. 89).

Again, in the Nineteenth Book, we are told (v. 303) that the γέροντες Ἀχαιῶν assembled in the encampment of Achilles, that they might urge him to eat. He refused; and he sent away the ‘other kings;’ but there remained behind the two Atreidæ, Ulysses, Nestor, and Idomeneus, ‘and the old chariot-driving Phœnix.’ The others are mentioned without epithet, probably because they had just been described as kings; and Phœnix is in all likelihood described by these epithets, for the reason that the term βασιλῆες would not include him (xix. 303-12).

On the whole then, and taking into our view that Phœnix was as a lord, or ἄναξ, subordinate to Peleus, and that he was a sub-commander in the contingent of Achilles, we may be pretty sure that he was not a βασιλεύς; if that word had, as has I think been sufficiently shown, a determinate meaning.

3. Though Patroclus was in the first rank of warriors he is nowhere called βασιλεὺς or Διοτρεφής; but only Διογενὴς, which is a word apparently used with rather more latitude. The subordinate position of Menœtius, the father of Patroclus, makes it improbable that he should stand as a king in the Iliad. He appears to have been lieutenant to Achilles over the whole body of Myrmidons.

4. Eurypylus son of Euæmon71, commander of a contingent of forty ships, and one of the ten acceptors of the challenge, is in one place addressed as Διοτρεφής. It is doubtful whether he was meant to be exhibited as a βασιλεὺς, or whether this is a lax use of the epithet; if it is so, it forms the only exception (apart from ix. 607) to the rule established by above thirty passages of the Iliad.

Upon the whole, then the evidence of the Iliad clearly tends to show that the title βασιλεὺς was a definite one in the Greek army, and that it was confined to nine persons; perhaps with some slight indistinctness on the question, whether there was or was not a claim to that rank on the part of one or two persons more.

Conditions of Kingship in the Iliad.

Upon viewing the composition of the class of kings, whether we include in it or not such cases as those of Meges or Eurypylus, it seems to rest upon the combined basis of

1. Real political sovereignty, as distinguished from subaltern chiefship;

2. Marked personal vigour; and

3. Either,

a. Considerable territorial possessions, as in the case of Idomeneus and Oilean Ajax;

b. Extraordinary abilities though with small dominions, as in the case of Ulysses; or, at the least,

c. Preeminent personal strength and valour, accepted in like manner as a compensation for defective political weight, as in the case of Telamonian Ajax.

Although the condition of commanding considerable forces is, as we see, by no means absolute, yet, on the other hand, every commander of as large a force as fifty ships is a βασιλεὺς, except Menestheus only, an exception which probably has a meaning. Agapenor indeed has sixty ships; but then he is immediately dependent on Agamemnon. The Bœotians too have fifty; but they are divided among five leaders.

Among the bodily qualities of Homeric princes, we may first note beauty. This attribute is not, I think, pointedly ascribed in the poems to any person, except those of princely rank. It is needless to collect all the instances in which it is thus assigned. Of some of them, where the description is marked, and the persons insignificant, like Euphorbus and Nireus72, we may be the more persuaded, that Homer was following an extant tradition. Of the Trojan royal family it is the eminent and peculiar characteristic; and it remains to an observable degree even in the case of the aged Priam73. Homer is careful74 to assert it of his prime heroes; Achilles surpasses even Nireus; Ulysses possesses it abundantly, though in a less marked degree; it is expressly asserted of Agamemnon; and of Ajax, who, in the Odyssey, is almost brought into competition with Nireus for the second honours; the terms of description are, however, distinguishable one from the other.

Again, with respect to personal vigour as a condition of sovereignty, it is observed by Grote75 that ‘an old chief, such as Peleus and Laertes, cannot retain his position.’ There appears to have been some diversity of practice. Nestor, in very advanced age, and when unable to fight, still occupies his throne. The passage quoted by Grote to uphold his assertion with respect to Peleus falls short of the mark: for it is simply an inquiry by the spirit of Achilles, whether his father is still on the throne, or has been set aside on account of age, and the question itself shows that, during the whole time of the life of Achilles, Peleus, though old, had not been known to have resigned the administration of the government. Indeed his retention of it appears to be presumed in the beautiful speech of Priam to Achilles (Il. xxiv. 486-92).

Custom of resignation in old age.

At the same time, there is sufficient evidence supplied by Homer to show, that it was the more usual custom for the sovereign, as he grew old, either to associate his son with him in his cares, or to retire. The practice of Troy, where we see Hector mainly exercising the active duties of the government – for he feeds the troops76, as well as commands them – appears to have corresponded with that of Greece. Achilles, in the Ninth Iliad, plainly implies that he himself was not, as a general, the mere delegate of his father; since he invites Phœnix to come and share his kingdom with him.

But the duties of counsel continued after those of action had been devolved: for Priam presides in the Trojan ἀγορὴ, and appears upon the walls, surrounded by the δημογέροντες, who were, apparently, still its principal speakers and its guides. And Achilles77, when in command before Troy, still looked to Peleus to provide him with a wife.

I find a clear proof of the general custom of retirement, probably a gradual one, in the application to sovereigns of the term αἴζηοι. This word is commonly construed in Homer as meaning youths: but the real meaning of it is that which in humble life we convey by the term able-bodied; that is to say, those who are neither in boyhood nor old age, but in the entire vigour of manhood. The mistake as to the sense of the term has created difficulties about its origin, and has led Döderlein to derive it from αἴθω, with reference, I suppose, to the heat of youth, instead of the more obvious derivation form α and ζάω, expressing the height of vital power. A single passage will, I think, suffice to show that the word αἴζηος has this meaning: which is also represented in two places by the paraphrastic expression αἰζήιος ἀνήρ78. In the Sixteenth Iliad, Apollo appears to Hector under the form of Asius (716):

ἀνέρι εἰσάμενος αἰζηῷ τε κρατερῷ τε.

Now the Asius in question was full brother to Hecuba, the mother of Hector and eighteen other children; and he cannot, therefore, be supposed to have been a youth. The meaning of the Poet appears clearly to be to prevent the supposition, which would otherwise have been a natural one in regard to Hector’s uncle, that this Asius, in whose likeness Apollo the unshorn appeared, was past the age of vigour and manly beauty, which is designated by the word αἴζηος.

Force of the term αἴζηος.

There is not a single passage, where this word is used with any indication of meaning youths as contra-distinguished from mature men. But there is a particular passage which precisely illustrates the meaning that has now been given to αἴζηος. In the Catalogue we are told that Hercules carried off Astyoche79:

πέρσας ἄστεα πολλὰ Διοτρεφέων αἰζηῶν.

Pope renders this in words which, whatever be their intrinsic merit, are, as a translation, at once diffuse and defective:

‘Where mighty towns in ruins spread the plain,And saw their blooming warriors early slain.’Cowper wholly omits the last half of the line, and says,

‘After full many a city laid in dust’…

Chapman, right as to the epithet, gives the erroneous meaning to the substantive:

‘Where many towns of princely youths he levelled with the ground.’

Voss, accurate as usual, appears to carry the full meaning:

‘Viele Städt’ austilgend der gottbeseligten Männer.’

This line, in truth, affords an admirable touchstone for the meaning of two important Homeric words. The vulgar meaning takes Διοτρεφέων αἰζήων as simply illustrious youths. What could Homer mean by cities of illustrious youths? Is it their sovereigns or their fighting population? Were their sovereigns all youths? Were their fighting population all illustrious? In no other place throughout the Iliad, except one, where the rival reading ἀρηιθόων is evidently to be adopted, does the Poet apply Διοτρεφὴς to a mass of men80. If, then, the sovereigns be meant, it is plain that they could not all be youths, and therefore αἴζηος does not mean a youth. But now let us take Διοτρεφὴς in its strict sense as a royal title only; then let us remember that thrones were only assumed on coming to manhood, as is plain from the case of Telemachus, who, though his father, as it was feared, was dead, was not in possession of the sovereign power. ‘May Jupiter,’ says Antinous to him, ‘never make you the βασιλεὺς in Ithaca: which is your right,’ or ‘which would fall to you by birth81:’

ὅ τοι γενεῇ πατρώϊόν ἐστιν.

When Telemachus answers, by proposing that one of the nobles should assume the sovereignty. Lastly, upon declining into old age, it was, for the most part, either as to the more active cares, or else entirely, relinquished. Then the sense of Il. ii. 660 will come out with Homer’s usual accuracy and completeness. It will be that Hercules sacked many cities of prince-warriors, or vigorous and warlike princes.

Thus, then, it was requisite that the Homeric βασιλεὺς should be a king, a könig, a man of whom we could say that actually, and not conventionally alone, he can, both in mind and person. Such was the theory and such the practice of the Homeric age. There is not a single Greek sovereign, with the honourable exception of Nestor, who does not lead his subjects into battle; not one who does not excel them all in strength of hand, scarcely any who does not also give proofs of superior intellect, where scope is allowed for it by the action of the poem. Over and above the work of battle, the prince is likewise peerless in the Games. Of the eight contests of the Twenty-third Book, seven are conducted only by the princes of the armament. The single exception is remarkable: it is the boxing match, which Homer calls πυγμαχίη ἀλεγεινὴ82, an epithet that he applies to no other of the matches except the wrestling.

But his low estimation of the boxing comes out in another form, the value of the prizes. The first prize is an unbroken mule: the second, a double-bowled cup, to which no epithet signifying value is attached. But for the wrestlers (a contest less dangerous, and not therefore requiring, on this score, greater inducement to be provided,) the first prize was a tripod, worth twelve oxen; and the second, a woman slave, worth four. What, then, was the relative value of an ox and a mule not yet broken? Mules, like oxen, were employed simply for traction. They were better, because more speedy in drawing the plough83; but, then, oxen were also available for food, and we have no indication that the former were of greater value. Without therefore resting too strictly on the number twelve, we may say that the prize of wrestling was several times more valuable than that of boxing. Again, the second prize of the foot-race was a large and fat ox, equal, probably, to the first prize of the boxing-match84. Epeus, who wins the boxing-match against the prince Euryalus, third leader of the Argives, was evidently a person of traditional fame, from the victory he obtains over an adversary of high rank. But Homer has taken care to balance this by introducing a confession from the mouth of Epeus himself, that he was good for nothing in battle85;

ἦ οὐχ ἅλις, ὅττι μάχης ἐπιδεύομαι;

an expression which, I think, the Poet has used, in all likelihood, for the very purpose of shielding the superiority of his princes, by showing that this gift of Epeus was a single, and as it were brutal, accomplishment.

Accomplishments of the Kings.

As with the games, so with the more refined accomplishments. There are but four cases in which we hear of the use of music and song from Homer, except the instances of the professional bards. One of these is the boy, who upon the Shield of Achilles plays and sings, in conducting the youths and maidens as they pass from the vineyard with the grapes. It is the bard, who plays to the dancers; but his dignity, and the composure always assigned to him, probably would not allow of his appearing in motion with such a body, and on this account the παὶς may be substituted; of whose rank we know nothing. In the other cases, the three persons mentioned are all princes: Paris is the first, who had the lighter and external parts of the character of a gentleman, and who was of the highest rank, yet to whom it may be observed only the instrument is assigned, and not the song. The second is the sublime Achilles, whose powerful nature, ranging like that of his Poet through every chord of the human mind and heart, prompts him to beguile an uneasy solitude by the Muse; and who is found in the Ninth Iliad86 by the Envoys, soothing his moody spirit with the lyre, and singing, to strains of his own, the achievements of bygone heroes. Again, thirdly, this lyre itself, like the iron globe of the Twenty-third Book, had been among the spoils of King Eetion.