The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

The first point to make is that the Welsh castles were exceptional, not only because of the incredibly impressive focus of men, materials and money, but because they were all built from scratch. Most English castles were a product of hundreds of years of piecemeal addition; very few new castles were built after 1150. Therefore, unusually, Edward had the opportunity to create a series of brand-new ideal forts, building what were probably the greatest military achievements of their age in Western Europe. The design of the Welsh castles brought together ideas that had been tried and tested at Dover and the Tower. For instance, none of them has a great tower or keep. Their most prominent feature, and where the prime accommodation lay, was the gatehouse. It was the gatehouse that had proved decisive during the siege of Dover, and the new defences at Dover, particularly the Constable Tower, emphasised its importance. But there was perhaps more than military necessity in the prominence given to gatehouses. Since Saxon times the English had favoured the gatehouse as a sign of status (p. 52), and the Welsh castles of Edward I reinforced this as a major feature in English architectural design (p. 146).39

Finally, both Conway and Caernarvon castles effectively contained royal palaces.40 This is an important point because neither Henry III’s works nor those of Edward I were confined to defence. Henry III transformed his castles into major and comfortable residences for himself; his works at Dover and the Tower included new palaces, as did those at Windsor and Winchester. After his marriage in 1236, yet more building was commissioned to provide suitable accommodation for the queen. These royal works reflect a wider move by magnates who were making their castles more comfortable and spacious. The Cliffords at Brougham Castle, Cumbria, were typical in setting out to extend and modernise their Anglo-Norman great tower in 1300. They added an elaborate gatehouse to its face, raised it by a storey and added fine rooms, including a vaulted oratory (fig. 117). Brougham was no longer a cold northern fortress; it was a commodious and fashionable residence.

Fig. 117 Brougham Castle, Cumbria, is a lesson in how to transform a severe Norman great tower into a compact but luxurious residence. The bottom three storeys date from around 1200 and contain a store, the castle’s hall and above that the original lord’s chamber. The storey above, with its fancy oratory and big fireplace, date from a century later and was added by Robert Clifford.

A Capital City

It was during the reign of Edward I that London became a capital city in the modern sense of the word, displacing Winchester as the seat of the state and the focal point for English identity, language and law. Its population was perhaps as large as 100,000, much smaller than Paris but four times the size of its nearest rival, Norwich. The years after 1300 saw London consolidate its position as the engine-house of England’s economy. By 1306 it exported more wool than Boston, and by 1334, in terms of taxation, London was five times richer than Bristol, her nearest competitor.41

London was still surrounded by a wall with six gates, Roman in origin, and on a number of occasions during the Middle Ages these were manned to defend the City. Yet the population had already burst through the walls, especially in the west, where buildings lined the streets of the Strand and Holborn. Within the city most of the major buildings and structures that dominated its skyline to the Reformation had already been founded. The Tower and St Paul’s Cathedral have already been mentioned, but London also had monasteries and 140 parish churches, as well as London Bridge, 906ft long with 19 arches.

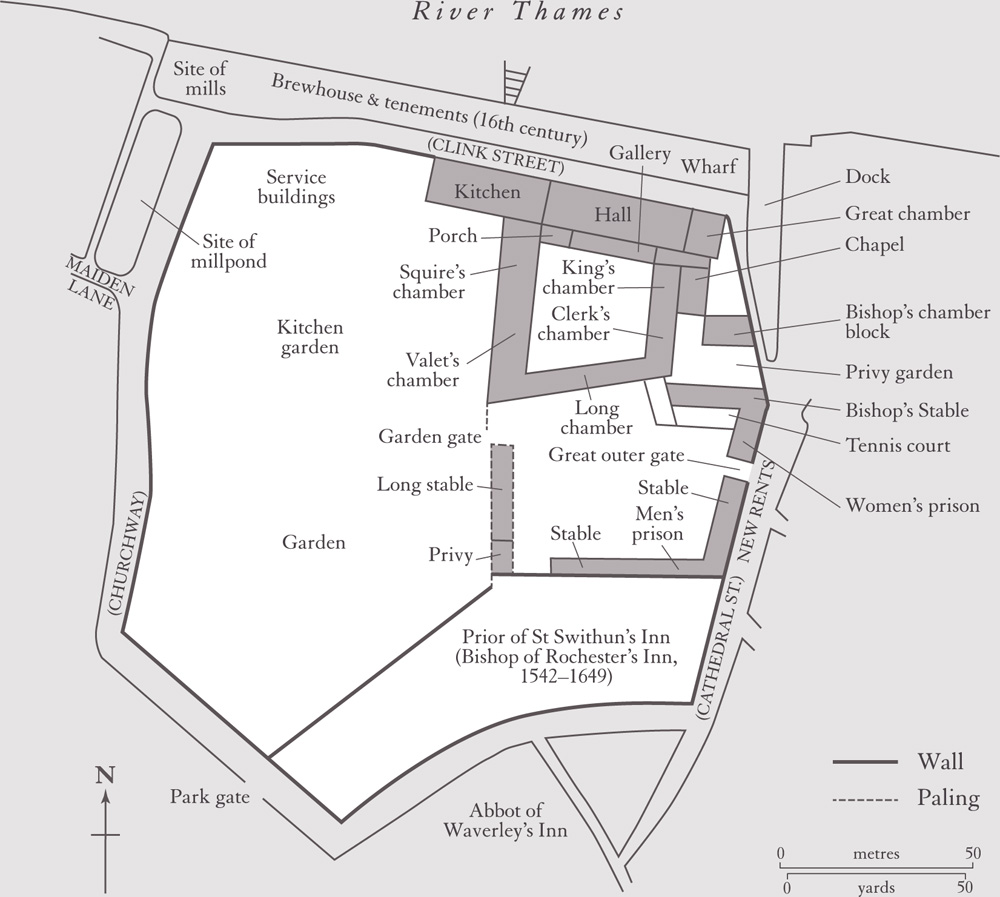

The rich and powerful had houses in London from 1100, but from 1300 large numbers of bishops and abbots, and then lay nobles, built great houses or inns in London, seeking to be close to Westminster and the law courts, and to trade with each other. We have already met the pluralist Bogo de Clare (p. 134), who was typical of the very rich in having a house near Aldgate but only 950ft away also owning a substantial wardrobe – essentially an office where he could trade, entertain business contacts and conduct his financial affairs. His wardrobe had a courtyard with a well and a lawn, perhaps a chapel, too. Between 1285 and 1286 Bogo spent £375 on supplies through his wardrobe. This was big business for everyone concerned and demonstrated that aristocratic houses were crucial to the economy of the city. Their wealthy occupants spent heavily on supporting their households and equipping themselves with the latest luxuries. When Richard Swinfield, Bishop of Hereford, brought his household to London in 1291, his expenditure trebled from £1 to £3 a day.42 The houses of men such as Bogo were generally set back from the street in courtyards approached by a gatehouse. Their owners would often build and rent out shops on the street front, making their houses to an extent self-supporting. At the back of the courtyard was generally the great hall and an attached chamber built up over a vaulted undercroft. Many also had towers that lifted their owners above the noise, smell and confusion of the streets to daylight and spectacular views over the rooftops. No single 14th-century house or wardrobe survives, but in Southwark parts of the Bishop of Winchester’s palace do, and these give us a glimpse of the magnificence of the richest of the residences (fig. 118). Winchester Place was started in about 1200, and was extended and altered right up to the Reformation. The bishop had a separate chapel and, at right angles to this, was a suite of rooms built in the late 1350s containing a number of fine chambers, including a study and latrines. The new rooms overlooked gardens. The kitchen and domestic buildings lay to the west of the hall. The whole was bounded by walls and supplied by extensive stabling. This latter point is important as stabling was a huge problem, rather like car parking today. Pasture, fodder and a place to stable horses were crucial to the efficient existence of a nobleman, and good stables in central London were vitally important for a man of wealth.43 English architecture in the period from 1220 to 1350 displays the confidence that comes with wealth and independence. Architects had mastered both the structural capabilities of Gothic architecture and its decorative possibilities. Patrons wanted to translate their ambitions into stone, timber, glass and fired clay, and were not ashamed of extravagant display. England was largely made up of the estates of the aristocracy, the Church and the Crown. All created landscapes that were in equal measure devoted to power, pleasure and production. Their economic lessers aped them, but also made their own distinctive contribution. The Crown did not exclusively set the way bishops, aristocrats and merchants created new forms of building. For everyone, however, architecture was, as always, about display, whether it was at Winteringham (p. 124), All Saints’, Buckworth (p. 136), or Penshurst Place (p. 143).

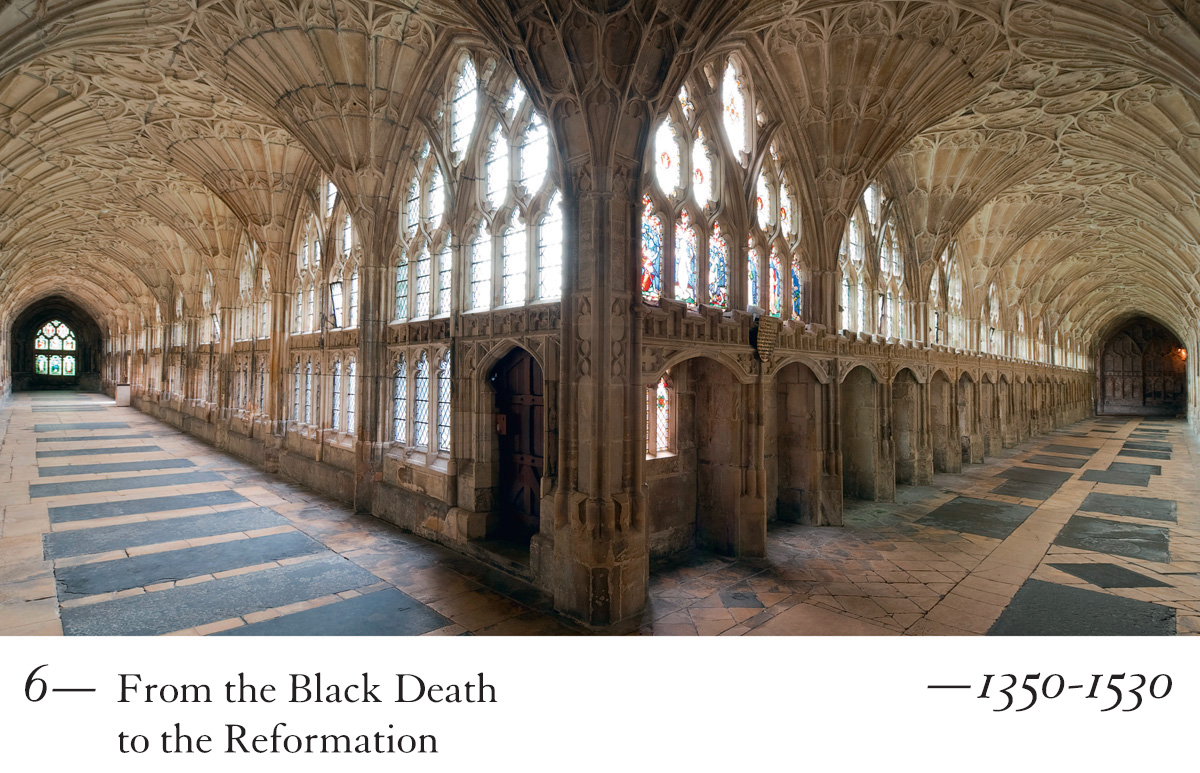

The years between 1350 and 1530 produced a distinctive architectural language of considerable beauty and sophistication in England that was quite different from its continental counterparts. This individuality was to remain a hallmark of English building during the following century.

Introduction

Between the Black Death and the Reformation building in England entered a long period of architectural consensus. For nearly 200 years designers worked with an architectural language that, with relatively minor modulation and a greater or lesser degree of elaboration, retained its essential stylistic components. Through this long period new building types developed, new materials became fashionable and the way people lived, thought and worshipped changed. Yet, while the differences in buildings built between 1200 and 1300 are readily discernible, the same cannot be said of buildings built between 1400 and 1500. Precisely dating 15th-century buildings on stylistic grounds alone is a hazardous business, but the skills to do the same for 13th-century buildings can be readily developed.

Generations of scholars have made many attempts to explain this, each discrediting the views of the previous generation but each adding to the subtlety and complexity of our understanding.1 Yet there are some important points that help. Gothic was an international architectural language, but after 1300 it acquired, if you like, many national dialects. Whilst Henry III’s Westminster Abbey (p. 127) and St Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster (p. 144), were consciously influenced by French models, this cannot be said of buildings after 1350. Architects looked to domestic models rather than to France, and so England, Spain, France, Flanders and elsewhere developed their own indigenous varieties of building. These varieties or dialects sometimes fed from one another; others acquired a particularly distinct tone. In England the dialect was very individualistic – and quite unlike those that developed elsewhere – and formed a national school of design that was strengthened by a close-knit network of masons and architects operating in a geographically defined nation state.2

This turning inwards of architectural design took place against a tumultuous background of international warfare, civil war, political instability, and economic and social disaster. It is this mix of apparent instability on the one hand with architectural consensus on the other that this chapter explores.

A Century of Crisis 1300–1408

Although 13th-century England was rich and populous, by 1300 both wealth and population growth had reached a temporary peak, with the century that followed bringing financial setbacks and a decline in population. Underlying many of the problems was a very modern concern – climate change. Between 1290 and 1375 the British climate became unstable and unpredictable; a series of wet summers prevented crops from ripening, rotted seed in the ground, and nurtured pests and disease, while coastal flooding inundated thousands of acres and torrential rain made thousands more unusable. Between 1315 and 1322 there was crop failure and widespread famine, killing perhaps half a million people. Starting in the 1330s the countryside began to contract, villages were abandoned, clay and sandy soils were left for more fertile areas.3 During the 13th-century expansion in Dartmoor hamlets and farmsteads had been built on agriculturally marginal land. In 1300 in the southern hamlet at Hound Tor there were four longhouses and seven ancillary buildings. As the climate deteriorated the farmers who occupied these built stone walls to keep the moorland from eating up their fields. Initially they must have had success, but in the 1330s they built corn driers to combat the effect of wet summers. This cannot have been enough, for the whole settlement was abandoned less than twenty years later.4

A better-developed agricultural economy might have resisted the effects of climate change but climatic factors brought an immature system to its knees, particularly at the margins. A second global factor undermined 13th-century stability – a failure in the money supply. This was partly caused by a genuine shortage of silver; the mines simply couldn’t produce enough to supply the mints as well as the luxury-goods market. But in part it was a result of taxation demands made by the Crown to pay for war, meaning that in the 1330s and 40s there was often no money available to buy goods.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов