The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

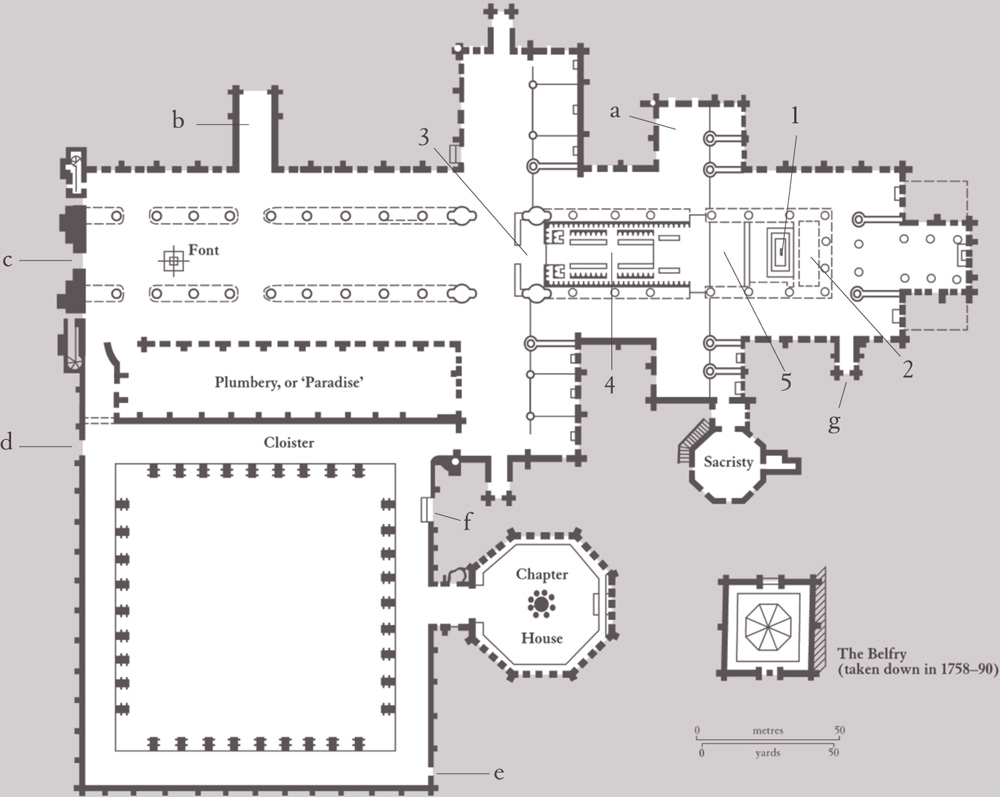

Each bay of the main and eastern transepts held its own altars, and these, together with those at the east end, ensured that there were 17 altars available for the 50 cathedral canons to say Mass. The clergy had their own entrance to the cathedral through the north end of the eastern transept, while the laity entered through an elaborate north porch in the nave. The Use of Sarum specified that on major feast days the clergy and choir would process out of their part of the church, round the cloisters and, on the most important feasts, to the front of the cathedral and back in through the west doors. The west doors in cathedrals were generally reserved for ceremonial use only.24

At the east end of the cathedral was a large chapel dedicated to the Trinity. In practice this was used for the daily Mass dedicated to the Virgin Mary. As noted above, a daily Lady Mass was an innovation of the 12th century, the Feast of the Conception of the Virgin having been introduced in the 1120s. The cult of the Virgin had a major architectural impact, with Lady chapels being added to greater churches and cathedrals all over England. In cathedrals in which the east end was rebuilt, such as at Lincoln, the Lady chapel tended to be the easternmost part of the church, but other places were appropriated as Lady chapels, too, most famously at Ely, where the monks built a new chapel on the north side between 1335 and 1353. Here, although brutally mutilated during the Reformation, is a symphony in stone to the Virgin. Scenes from her life inspired by a sacred text encrust the lower walls and previously filled the vast windows.

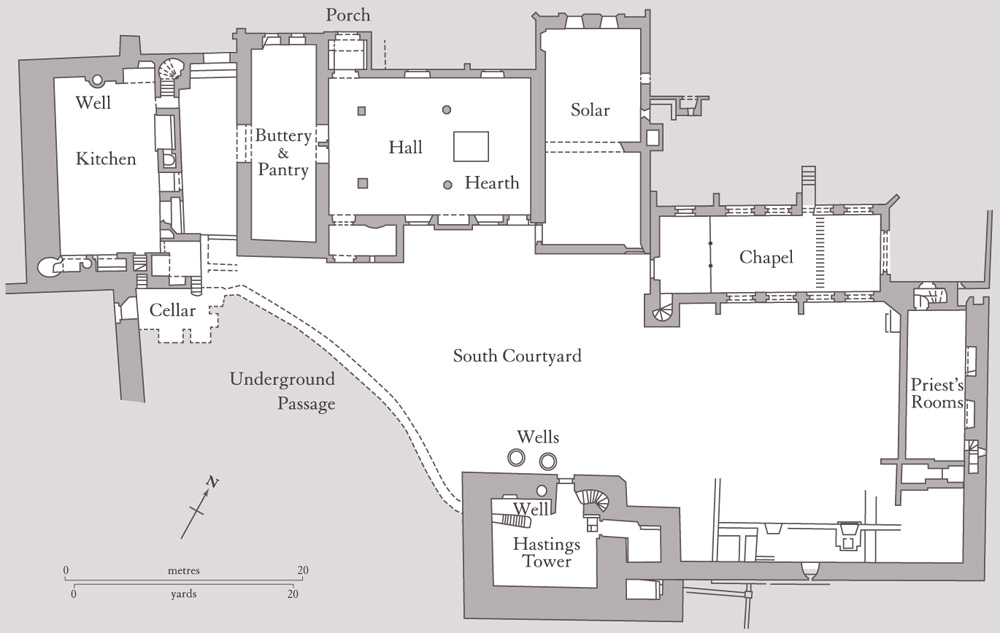

Access to the great hall was no longer from a door in the centre of one of its long walls but through a door at the lower end; this door led to a passage that was screened off from the rest of the hall by a timber partition. Doors from the kitchen, from the buttery (for beer) and pantry (for bread) would lead into this enclosure, which became known as the screens passage. This more integrated arrangement allowed lords to spend more time in the comfort of their chambers while coming and going through their halls. This private space was a badge of rank, part of the charisma of greatness and wealth. To be inaccessible was to be important, as it enabled favour to be shown and intimacy to be conferred and withdrawn. More exclusive rooms that often included private chapels (or oratories) were further symbols of exclusivity.32

Fig. 111 Lincoln, Bishop’s Palace: reconstructed as it would have been seen from the great courtyard of the palace. To the left is the great hall with its porch and bay window; on the right there is the kitchen linked to the hall by a passage. The palace was built on sloping ground and so the kitchen was raised up on a vault.

Many of these innovations in domestic planning were led by the bishops, who were single, rich and less conservative in outlook than the monarchy or the magnates. In the shadow of Lincoln Cathedral lies the now ruined bishop’s palace, once among the most lavish buildings in the kingdom. Here modern-day visitors can see one of the earliest instances of a kitchen linked to the lower end of a hall, with three doors serving the buttery, pantry and kitchen (fig. 111). The hall was started in the 1220s and about 20 years later Bishop Grosseteste set out 23 rules for the smooth running of a household. In these he was careful to cover appropriate behaviour in the hall, and rules for the serving, seating and attire of dinner guests.33 Such household regulations were increasingly enforced by chamberlains, the guardians of the lord’s dignity and privacy. The chamberlain was not the only officer in a great household as, by 1100, most aristocrats were accompanied by men holding posts such as steward, butler, constable, marshal, clerk and huntsman. These people – and their more humble followers – were the human backdrop to aristocratic power: a household such as that of Bishop Grosseteste would have had as many as eighty attendants, that of a duke or an earl perhaps twice that.34

These structured and hierarchical households with their integrated kitchens, halls and chambers presented new architectural opportunities. Stokesay Castle, Shropshire, is a miraculously unaltered house of the 1280s built by the super-rich wool merchant Laurence of Ludlow, an early example of a man, enriched by trade, who set himself up as a country squire. Laurence built himself a fine great hall with tall windows and a central hearth; at its south end was a block containing his own chambers, leading on to a tower with three large, well-lit rooms. At the lower end of the hall were more chambers, possibly for guests or perhaps his family (fig. 113).

Fig. 112 Penshurst Place, Kent; the great hall. A remarkable, perfectly preserved 14th-century great hall now only lacking its central louvre to let out the smoke. Originally there were large-scale murals depicting men-at-arms under gabled canopies.

Fig. 113 Stokesay Castle, Shropshire, the west elevation of the great hall and the north tower built 1285–1305. The hall windows were not glazed but closed with wooden shutters.

One of the most innovative features of Stokesay is the great hall roof. It is one of the first to achieve an impressive span without aisle posts. A post-less hall was the holy grail of early medieval secular architects. Posts cluttered up the hall, reducing flexibility and visibility, and from the 1220s experiments had taken place to create wide spans without the need for posts. After about 1310 no hall had posts – all were clear, unsupported spans.35

Stokesay is a modest house; a more spectacular example, almost as well preserved, is Penshurst Place, Kent, begun by Sir John Pulteney between 1338 and 1349. Pulteney emerged as a financier in the 1320s and, thanks to a shrewd financial nose, became one of the richest men in England. At the heart of his house was a magnificent great hall, very much today as Pulteney left it. Entered by a two-storey porch and lit by tall windows with fine tracery, the hall is covered with a vast chestnut roof (fig. 112). The trusses are held together by collar-beams resting on richly moulded purlins. From the collars arched braces come down to another richly carved horizontal member, the wall plate. Each brace terminates in a life-size wooden figure originally standing on a stone corbel.

This was the social centre of Pulteney’s universe. Here he sat at table on his tiled dais facing a wooden screen bearing a gallery for musicians. Between the windows were full-size paintings of men-at-arms. With a fanfare from above, his food would be brought from the kitchens, under the screen past a fire blazing in the centre of the room and to his table. From his dais a spiral stair led up to a large chamber lit on three sides, heated by a fireplace and furnished with a latrine. Penshurst and Pulteney were as grand as it got, unless, that is, you were royalty.

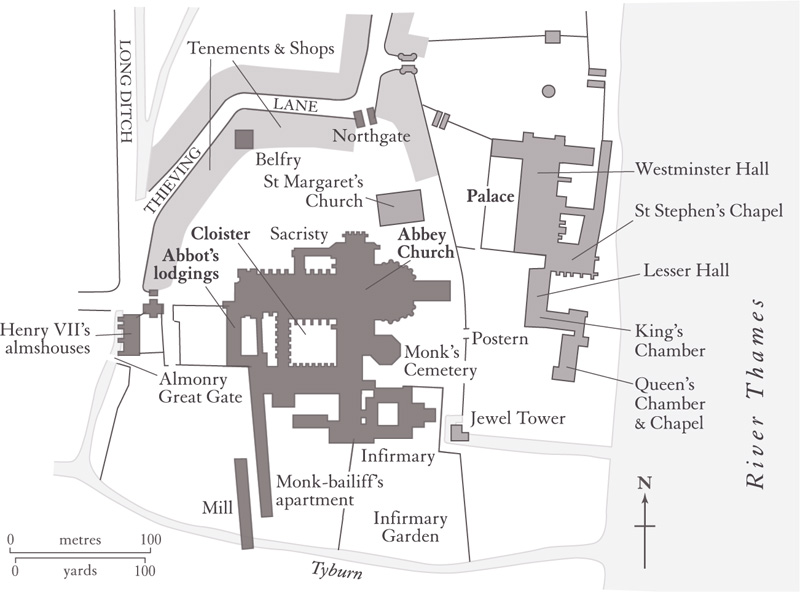

Fig. 114 Map of Westminster in the later Middle Ages.

The English word ‘palace’ comes from the Latin ‘palatium’, referring to the principal residence of the Roman emperors on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Westminster was the palace of the English kings and every medieval monarch contributed something to its adornment. By the time Henry III came to the throne William Rufus’s great hall (p. 78) had already been joined by another hall to its south, smaller and more convenient for everyday use. There was a chamber at right angles to this chamber, its eastern windows overlooking the Thames (fig. 114). Henry III remodelled the chamber, giving it new windows, fireplace, roof and a small oratory. This room, soon to be known as the Painted Chamber after its extensive murals, was Henry’s bedchamber, with his bed in a curtained enclosure and a small squint window providing a view of the altar in the oratory. To the south of the Painted Chamber was the queen’s chamber and chapel, newly constructed by Henry III for Queen Eleanor between 1237 and 1238.36

Westminster Palace, with its conglomeration of fine chambers, did not stand alone. Part of Henry III’s conception was for his palace and Westminster Abbey to be linked physically and institutionally, with the abbey serving as a private monastery to his principal residence. The chapter house, for instance, was always intended to act as a meeting place in which to discuss state business (and became a meeting place of parliament). This was typical of the intense personal interest that Henry took in the construction of the palace and the abbey that made both so influential.

Defence of the Realm

The crisis of 1216–17 (p. 120) and the continued tension between the Crown and the magnates caused some fundamental questions to be asked about the design of castles. It must be remembered that Dover, the most important and powerful castle in England, had been besieged in 1216 and nearly taken. At the start of Henry III’s reign it was time to review how these powerhouses were built. Henry III spent the following 30 years completing the outer defensive walls at Dover, building outworks and what was probably the most impressive and complex gatehouse to any castle in England (fig. 115).37

Dover was key to the defence of the kingdom, as had been demonstrated in 1216–17. No less so was the Tower of London. Built to overawe Londoners, and by Henry III’s reign the home of the royal treasury and arsenal, it was central to the power of the monarchy. Relations with the city had, however, been strained, and Henry felt it vital to bring this fortress up to standard, too.

Fig. 115 Dover Castle, Kent; the Constable’s Gate, probably the largest gatehouse ever built in England. Begun in 1217 as the new principal entrance to the fortress, but also to contain a residence for the castle’s permanent chief, the Constable.

At the Tower of London, in the 1220s and from the late 1230s, Henry III re-planned the defensive circuit around the Conqueror’s White Tower, building a massive curtain wall protected by a series of circular and D-shaped towers and a 160ft-wide moat. A new gatehouse and barbican faced the City of London, and the White Tower assumed its current name thanks to its first all-over coat of whitewash. Henry’s work, which increased the walled area of the Tower by at least an acre, probably remained unfinished; part of it certainly collapsed, and it was left to Edward I to complete the fortification of the Tower between 1275 and 1285. Edward threw a second wall around the one built by his predecessor, digging a new moat and creating a complex series of outworks and gatehouses as a new entrance. The Tower of London was now the first coherently planned concentric fortress in England (fig. 116).

Fig. 116 The Tower of London today. Although altered in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Tower is still recognisably a concentric fortress with rings of defences and, bottom right, an elaborate system of gatehouses, drawbridges and causeways that secured its entrance.

To enter, it was now necessary to pass from Tower Hill on to the Lion Tower, a semicircular enclosure surrounded by a moat and guarded by two gates and a drawbridge. From here the would-be visitor had to pass through the twin-towered Middle Tower, a gateway defended by a drawbridge, gateway and two portcullises, before passing onto a parapeted causeway across the moat. Here visitors were confronted by a second twin-towered gatehouse, the Byward Tower, also defended by a gate, portcullises and a drawbridge. King Edward I is known, rightly, as one of the great builders in English history. As well as substantial work in England, over a 25-year period – and at the cost of £80,000 – he built a series of castles and fortified towns in North Wales as part of his campaign to conquer and subdue the Welsh. Caernarvon, Conway, Harlech and Beaumaris, for example, still stand witness to this remarkable chapter in royal patronage. As these buildings are in Wales they fall outside the scope of this book, yet it is necessary to ask what influence, if any, did this gargantuan building programme carried out for an English king with English labour and finance have on the development of English architecture?38