The Building of England: How the History of England Has Shaped Our Buildings

Fig. 93 The construction of the nave of Westminster Abbey is one of the most remarkable stories in English building. Building began in the east in 1259–72, and subsequent abbots and masons continued the design from the 14th to the 16th century in exactly the same style. Though the inspiration was at first French, the details used over the long construction period are progressively more anglicised.

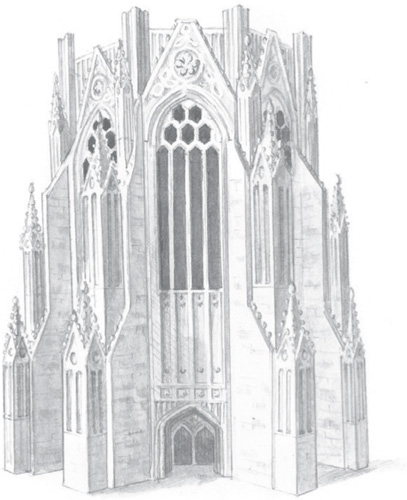

Nor was it alone, for England’s largest and most important cathedral was independently following a similar path. From the 1250s the monks of Old St Paul’s began to rebuild their east end with a massive extension that would make it the longest cathedral in England, whose exterior shared the richness and decoration of Westminster Abbey (fig. 92). A third London building encapsulated many of the new features displayed in the great churches. This was St Stephen’s Chapel, the main royal chapel at Westminster Palace, which Edward I started to rebuild in 1292. Its building history is long and complicated, covering 56 years, only being finally completed by Edward III after 1348 (pp 157–8). Yet the chapel was the most prominent and architecturally magnificent royal commission of its age, and no self-respecting mason or patron was ignorant of its style.

To understand the appearance of buildings in the period from 1250 to 1350 it is best to look at the individual elements since the focus of architectural innovation was on decoration, not on the underlying architectural skeleton. It is hard to convey the importance of decoration in medieval architecture to the modern spectator, as so little survives. The Reformation and the Civil War dealt horrible blows to the greatest English medieval buildings, stripping most of them down to their bare bones. This has led to a loss of meaning, for the architectural bones were the skeleton for a programme of communication through sculpture and paint. Church buildings were designed to represent the kingdom of heaven, and were intended as a signpost and the gateway to paradise for mortals.13

The most important new decorative element was undoubtedly window tracery. It was possible, using lancets grouped together, to let in more light, but it was still obvious that these were individual windows with sections of wall between them. The invention of tracery allowed really big windows to be built without bits of wall in the middle. The adoption of bar tracery at Binham Priory, Norfolk, at Netley Abbey, Hampshire, and at Westminster Abbey and Palace immediately made anything built before the 1250s look old-fashioned (compare figs 58, 94). Windows were now not only a gap in the wall; they were transformed into one of the primary vehicles for decoration and elaboration. Part of this was the extraordinary variety of the tracery, but a great deal of the effect was achieved by advances in glazing technology.

From 1300 a much paler and more translucent type of yellow stain was introduced, thinner glass was being manufactured and the designs were being painted with better, finer brushes. All of these advances let more light into churches. The west window at York Minster, which was glazed in 1339 by Master Robert with the extensive use of yellow stain, can be contrasted with the much heavier, darker windows in the lancets of Canterbury Cathedral (figs 60 and 94). In the York window it is also apparent that stained-glass artists had mastered the use of perspective. Windows depict figures under canopies and vaults similar to, and fully integrated with, those in the architecture around them.14

The narrow lancet windows in early Gothic churches let in little light, creating a mystical and intimate effect. From the early 14th century larger windows and larger east ends made it easier to see the increasingly elaborate rituals that were being performed. These changes can be seen in churches such as St Denys’s, Sleaford, Lincolnshire, with its wild, flowing tracery and west end covered in carving, or Holy Trinity, Hull, begun in around 1300 (fig. 95). Holy Trinity is one of England’s biggest parish churches and the first to be largely built of brick. Its chancel and transepts have some of the most inventive and beautiful traceried windows of their age, flooding the presbytery with light. Outside, the buttresses have canopied niches and parapets carved with wavy patterns.15

Fig. 94 York Minster nave, looking west towards the great west window commissioned in 1339 – it is 55ft high and of eight lights. The whole nave makes the most of the possibilities of big windows, suppressing the visual impact of the triforium by linking it to the clerestory using continuous mullions.

Fig. 95 Holy Trinity, Hull: the east end of the church of around 1300–20. The rich flowing tracery lights the retrochoir. The internal fittings of the choir were funded by the city corporation from a wool tax.

Fig. 96 Eleanor Cross, Geddington, Northamptonshire, 1291–4. Edward I erected twelve crosses marking the nightly resting places of the coffin of his wife, Eleanor of Castile, as it travelled to London. The monument contains canopied niches for statues.

The second fundamental decorative element of the period was the niche. These miniature vaults with a triangular gable sheltering an arch can be found, in large scale, on the outside of churches, most prominently on the west front at Wells Cathedral in the 1220s, but from the 1260s they begin to shrink in scale and become a decorative component often coupled with pinnacles. Perhaps the most prominent use of this combination was in the series of monuments Edward I erected to his queen, Eleanor of Castile. Eleanor died in 1290, and within a year or so twelve crosses had been erected near the religious houses at which her body lay on its journey from Nottinghamshire to Westminster (fig. 96).16 The crosses displayed a sort of micro-architecture of the type that can be found in contemporary metalwork and manuscripts and that was also well suited to tombs. The tomb in Westminster Abbey of Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, who died in 1296, captures the full possibilities of the niche and pinnacle. The astonishing tomb of King Edward II at Gloucester Cathedral of about 1330 is even more exotic, almost Moorish, with niches with S-shaped or ogee tops (fig. 97). The ogee arch had been used in Venice in about 1250, but from the 1290s it was taken up by English architects and designers like nowhere else in Europe. It first started to be used in tombs, then in niches, and then in prominent structures such as the great rose window of St Paul’s Cathedral. The ogee arch gave an exotic, quasi-Eastern form to some of the greatest spaces of the era, such as the Lady Chapel at Ely. The most unforgettable of these is St Mary’s, Redcliffe, Bristol, a parish church that aspires to the grandeur of a cathedral. The hexagonal porch, encrusted with niches with forward-thrusting ogee arches, contains a door that defies architectural description and looks to have escaped from a maharaja’s palace.

Fig. 97 Gloucester Cathedral; the tomb of Edward II, c.1330–5. The effigy is of alabaster on a tomb chest clad in Purbeck marble, but it is the canopy that is a work of genius. It is a bewildering array of crockets, niches, pinnacles and buttresses, all originally painted as befitted a king.

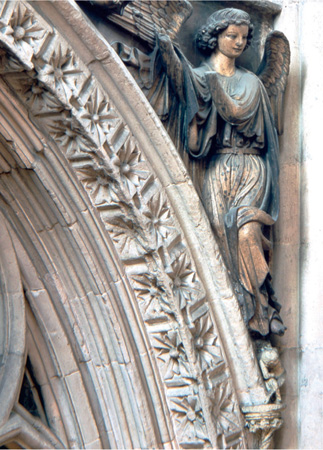

One of the innovations introduced at Westminster Abbey was the idea of interior large-scale sculpted human figures integrated with the structure and the wider decorative programme. Big figures had been used to great effect externally, particularly at Wells on the west front, but their internal use was another idea taken from the Sainte-Chapelle. At Westminster these figures either told stories from the lives of saints or emphasised some important part of the building (fig. 98). Such large-scale sculptures were to be taken up with huge enthusiasm, bringing colour and ornament to interiors.

Fig. 98 Westminster Abbey, south transept, south wall; an angel, elegantly accommodated in a spandrel, wings spread and swinging a censer – a perfect marriage of sculpture and architecture.

Fig. 99 Naturalistic foliage in the arches of the chapter house at Southwell Minster, Nottinghamshire, 1290s.

Medieval sculptors were not interested in accurately representing the human form, and figures – including those of people of great importance – were idealised. The statues of the queen on the Eleanor crosses do not capture the features of a real person; they represent an idealised Christian queen (fig. 96). Saints were instantly identifiable by how they stood or what they held; St Catherine had her wheel and St Peter always held the keys of heaven, while secular figures were identified by their badges or coats of arms. So Queen Eleanor’s crosses were encrusted with the badges of León, England, Castile and Ponthieu.

Yet startling naturalism can also be found, such as the heads carved for the corbels at Salisbury Cathedral, some tomb effigies, but most of all the brilliantly naturalistic foliage in the arches of the chapter house at Southwell Minster, Nottinghamshire (fig. 99). Capitals were now less often carved with narrative schemes (fig. 54), but corbels became a sort of portrait gallery, with hugely expressive images of what were probably real people. Carving – and painting – reflected life, rather than commenting on it as today.

Fig. 100 Exeter Cathedral was the last to be rebuilt almost in its entirety, over a period of 60 years from 1275; the building work was funded by a voluntary tax on the bishop and the chapter’s own income. A result of this is the perfect harmony of its interior, especially the nave, shown here, with its extraordinary high vaults 300ft above the floor.

All these streams of embellishment are represented at Exeter. The Anglo-Norman cathedral there was rebuilt over a 60-year period beginning in 1275. Its new form was constrained by the decision to retain its 12th-century twin towers. Thus Exeter is characteristic of most Gothic cathedrals where bishops and deans grafted their new buildings onto older work. This meant that the Gothic parts normally followed the thick-wall technique of the Anglo-Normans, keeping cathedrals long and low with a stronghorizontal emphasis.

But that is where the conservatism ends, for a succession of bishops determinedly funded a rebuilding of the cathedral in the best modern style (fig. 100). Exeter is an extravaganza. Everything is multiplied: the piers are made up of 16 bunched shafts, and the spectacular vault is a forest of 22 ribs in each bay, creating the longest single continuous Gothic vault in the world. Everything was patterned, from bosses, through corbels to tracery. The west front was started by Bishop Grandison in around 1346, and while it might not have the balance or harmony of the west front of Wells, here every decorative element in the designer’s vocabulary is brought to bear as tiers of figures reside in canopied niches below, perhaps, the most fanciful window of its age (fig. 101). This frontage, like that at Wells, and elsewhere, was intended as a backdrop for the most important services of the year, particularly the processions of Palm Sunday. On this day a choir, hidden behind the façade, seemed to make the very statues, originally painted and gilded, sing.

Fig. 101 Exeter Cathedral; the west front. Originally (1320s–40s) the front had three great doorways, and the west window still remains from this period, but the image screen was added from the mid-1340s and figures were still being completed in the 15th century.

How People Worshipped

We have seen that from the late Anglo-Saxon period local churches were founded and endowed by landowners as acts of piety (p. 56). These patrons – and their successors – retained the right to appoint the priest to their church or, if they chose, to give away the income to endow a monastery, with the condition that their church be provided for. ‘Rector’ is the term given to the priest or the monastery entitled to the parish church’s income from tithes or other sources.

Many individual rectors took their responsibilities seriously and used the income for its proper purpose. However, when patrons decided to appoint members of their own family as rectors, the income was often simply treated as personal wealth. For instance, Bogo de Clare, the son of the Earl of Gloucester and Hereford, was rector of 24 parishes in 1291 with an income of over £2,000. This enabled him to live a life of considerable luxury while he neglected the parishes from which his income came. De Clare was an exceptional case, but a large minority of rectories were farmed for profit.

By 1300 only about half of all parishes had individual rectors; the incomes of the remainder had been transferred to monasteries, a small part of which was reserved for the employment of a vicar (which in Latin means ‘substitute’). So the wealthy church of St Mary’s, Whalley, Lancashire, with an income of over £200, had its income appropriated to the Cistercian monastery there. As parish costs were only £27, the abbey made an annual profit of £173. This system meant that the financial position of a medieval church varied not only with the size of its income but with who controlled it. The impact on churches themselves could be significant because – as we have seen above – responsibility for the fabric of the chancel fell to the priest. Non-resident rectors could ignore their responsibilities, as they did at St John the Baptist’s, Yarkhill, Herefordshire, where water poured through the roof onto the altar when it rained; monastic owners could be equally neglectful of their duties, preferring to keep the income for their own institutions.17

Yet there were positive aspects, too. The earliest church-building contract to survive relates to the chancel of All Saints’, Sandon, Hertfordshire, and dates from 1348. The church at Sandon was owned by the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral. The Sandon estate was worth over £30 a year, and the Dean and Chapter decided to demolish the old chancel and replace it with a new one with fashionable windows, a sedilia, piscina and an Easter sepulchre (to receive the Easter effigy of Christ). The priest there was also well equipped; in 1297 he had three sets of vestments, two enamelled processional crosses, a censer and an incense boat.18

Fig. 102 Much Wenlock Priory, Shropshire; the triple sedilia of the fine chancel added in the 1380s gives the church a beautiful and well-lit setting for its liturgy.

From the Saxon period individual experience of worship in local churches became progressively less intimate and more ceremonialised. At the same time churches became more complex and segregated. The increased focus on communion, following the doctrine of transubstantiation, led to the rebuilding of many chancels as a suitable setting for the celebration of the Mass. New chancels were longer with larger windows and had square ends, unlike the Anglo-Norman ones. The chancel remained separated from the nave by a wooden screen; few early screens survive, but there is a very rare in situ survival from about 1260 at St Michael’s, Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire (fig. 103). This not only shows that views of the chancel were actually quite good, but that holes were cut at a lower level to provide a view of the elevated host for those kneeling. Many chancels were provided with a separate door for the clergy so they could come and go independently from the nave. Altars were now universally built against the east wall and the priest would celebrate communion with his back to the congregation. Since the 9th century priests in larger parishes had not celebrated Mass alone, but from the 13th century chantry priests, assistants and deacons were increasingly present. This was a reason for the increased size of chancels but it also explains the building of special seats for the clergy on the south wall. These sedilia (from the Latin for ‘seat’), usually built in threes, were first seen in Anglo-Norman churches but became very popular in new chancels (fig. 102).

Fig. 103 St Michael’s, Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire; the mid-13th century chancel screen is a rare and early survival.

Fig. 104 St Mary the Virgin, Stanwell, Surrey. A piscina with a ledge for vessels (a credence) and a cupboard (aumbry).

The emphasis on the proper celebration of Mass meant that a small wash-basin or piscina was now provided for water to be poured into after sacred vessels had been washed. Nearby was often a cupboard or aumbry for the storage of precious items. Sedilia, piscina and aumbries provided opportunities for decoration and often had carved, arched or canopied frames; sometimes two or three were combined in a single decorative unit (fig. 104).

Just as the chancel became more actively defined as the sphere of the clergy so, during the 13th century, legislation was enacted making the construction and upkeep of the nave the responsibility of parishioners. From early times there had been no permanent furniture in the nave and the congregation might have brought their own wooden stools to sit on. By the late 13th century pews were introduced, associated with a greater emphasis on preaching and sermons stimulated by the Fourth Lateran Council. The earliest surviving pews are probably those at the beautiful St Mary and All Saints’, Dunsfold, Surrey, of 1270 to 1290 (fig. 105).19

During the 13th century many naves were extended by the addition of an aisle. These first appeared in churches in the hands of rich men or institutions who wanted to bestow greater status on their church by giving it the form of a basilica; aisles also provided them with more space for private side altars and elaborate processions, and for burial inside the church. Less wealthy churches added aisles for more prosaic reasons: a rising population meant that for every churchgoer in 1100 there were three in 1300 and aisles simply fitted more people in.20

From the 1270s the practice of knights and lords being buried in their parish church became common. This was in contrast with the practice in France, for instance, where the rich wanted to be buried in cathedrals and abbeys. In England the strong tie between the lord and his land led to a desire for successive generations to be buried in the churches nearest to their homes. One such place is the manor of Aldworth, Buckinghamshire, where the de la Beche family lived. Sir Robert de la Beche was knighted by Edward I and on his death in around 1300 was buried in St. Mary’s church with an effigy carved fully in the round, cross-legged with a hand on his sword. Eight other members of his family subsequently joined him. These figures of knights and their ladies are realistic and expressive but characteristically stiff (fig. 106). Although the effigies are now badly mutilated, the impact that such monuments could have on a church interior is obvious.21 Less assertive, but no less magnificent or skilled, were the great memorial brasses of the period, in which England led the way.

As well as building outwards parishes were also building upwards. Although there had previously been periods of tower building, there was a rash of new towers from the 1270s, many capped with spires either of lead-covered timber or stone. Stone spires were concentrated in the wealthy, stone-rich midlands from south Lincolnshire across Leicestershire, Huntingdon and Northamptonshire, down through Warwickshire to Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

A spire was a luxury. It had no practical or liturgical function; it simply proclaimed the technical skills of its architect and the wealth of its patrons. It is for this reason that spires were often products of competition. Competitive imitation was one of the ways in which new styles and specific, sometimes quirky, features spread. The concentration of elaborate Easter sepulchres in Lincolnshire or the stone chancel screens of the West Country are examples of features popularised locally. But towers and spires were often not simply the product of imitation; they were built to exceed their neighbours in size and beauty. In neighbouring parishes in Huntingdonshire are the churches of All Saints’, Buckworth, and St Peter and St Paul’s, Alconbury (fig. 107). Their handsome, solid spires with windows (lucarnes) are both broach spires; in other words they rise directly from the tower without a parapet. Built around 1300, they were the result of two villages in fierce competition.22

Fig. 105 St Mary and All Saints, Dunsfold, Surrey; remarkably early pews dating from 1270–90. Simple, robust, and just more comfortable than standing.

Fig. 106 St Mary’s Aldworth, Berkshire; one of the tombs to a member of the de la Beche family. The effigy lies under a canopy, defaced during the commonwealth, but still discernible as an extravagantly carved and cusped recess.

The experience of worship in a cathedral was very different from that in a parish church. Although liturgical practices varied between cathedrals, a good idea of what they were like can be gained by considering Salisbury. Salisbury was the only cathedral during the Middle Ages to be built from scratch. This was down to Richard Poore, first as dean and then as bishop. Poore was also responsible for codifying its liturgical practices, introducing an orderly and regular framework for the feasts of the Christian year that set out how each ought to be celebrated. These liturgical instructions, which became known as the Use of Sarum, were applied to all churches in his diocese and by the 15th century were almost universally used as a sort of standard form of church worship.

Fig. 107 St Peter and St Paul’s, Alconbury, Cambridgeshire. The church has a fine broach spire of c.1300 built, competitively, at the same time as neighbouring All Saints Buckworth.

Although it is not quite comparing like with like, it is useful to compare the plan of St Albans (pp 73–4 and fig. 42) with Salisbury (fig. 108) to show how things had changed since the 1080s.23 The most important principle was that the clergy had their own enclosed area. This was located in the cathedral’s east arm, which was itself of cruciform shape and thus a church within a church. The area was enclosed by screens and was six bays long, three for the choir and three for the presbytery (or chancel). The whole east arm was divided from the rest by a massive stone screen, the pulpitum, which had a central processional entrance.