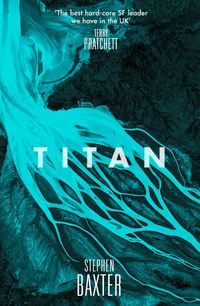

Titan

Suddenly, Benacerraf’s heart was racing. It was as if, cocooned in the warm, gentle comfort of the orbiter, she’d not accepted the reality of the obscure technical failures which had plagued the landing. But that hole in the wall was a violation, a rip in the universe.

Chandran reached down, stiffly. He pulled a pin and worked a ratchet handle.

A telescopic escape pole sprouted out of the ceiling over the hatch opening, forced out by spring tension. The steel pole snaked out of the hatch and bent backwards like a reed, forced back by the wind beyond the hull.

Chandran pulled a lanyard assembly out of a magazine close to the hatch. This was a hook suspended from a Kevlar strap. Chandran wrapped the strap around the pole, and fixed the hook to his pressure suit.

Holding the Kevlar strap in his right hand, he stepped up to the hatchway.

At the last second he turned. His mouth was half-open, a spray of spittle over the inside of his visor.

With awful slowness, he turned again. Clinging with both hands to the Kevlar strap, he stood on the rim of the hatchway. Then, ponderously, he let himself fall out.

Benacerraf could see Chandran sliding down the bent pole. He was twisting in the sudden gale, his orange pressure suit flapping against his flesh. Thread stitching on the Kevlar strap tore, absorbing some of Chandran’s momentum. He slid off the end of the pole, and started to fall away from the hull. Benacerraf could see his parachute opening, like a slowly blossoming flower.

For a moment, the egress seemed to have worked.

But then a gust picked up Chandran, and he soared in the air, his limbs loose as a doll’s.

He caromed into the black leading edge of the orbiter’s big port wing, against the toughest heatshield surface the orbiter carried. He fell over the wing’s upper surface, his parachute limp and trailing, and smashed into the big OMS engine pod at the rear of the orbiter.

After that he fell out of Benacerraf’s sight.

Sanjai Chandran – astrophysicist, father of two – was gone. It had taken just a second.

Benacerraf felt her stomach turn over, and saliva pooled at the back of her throat.

As the crew tried to bail out – tried to work through that dumb-ass tacked-on Shuttle egress system – Marcus White tried to focus on the job he’d volunteered for.

… He remembered coming down to the surface of the Moon, with Tom Lamb at his side:

He leaned forward in his spacesuit, against the restraints that held him standing in his place, trying to see. The LM went through its pitchover manoeuvre, and suddenly there was the Moon below him, a black and white panorama, as battered as a B – 52 bombing range, the shadows long in the lunar morning. There was too much detail, almost a crowd of craters. Really, it was nothing like the sims, with their little cameras flying over plaster-of-paris mocked-up landscapes.

But there was his target, the little collection of eroded craters they’d dubbed the Parking Lot, almost lost in that black and white sea of craters. ‘Hey, there it is,’ he’d said. ‘Son of a gun, Tom. Right down the middle of the road …’

The Moon’s surface had plummeted up to meet them; they were coming in like a bullet, and he’d tipped the LM back to slow it, and the eight-ball had tilted sharply …

Shit, shit. Focus, you old asshole.

It was Benacerraf’s turn.

She took a fresh lanyard assembly from the magazine, hooked into her suit, and slid it over the pole. Then she stepped up to the rim of the hatch. She clung to a handhold there, facing the air, framed by metal.

She could sense the wind, just inches away from her. The hull of the orbiter was still hot from the frictional heating of the entry, and she could feel its warmth, seeping through her boots. To her left, the wing and tail assembly were huge, blocky, black and white shapes.

And, far below, astonishingly far, she could see the Mojave. It was a brown plain, gently curving like a shallow dome, crisscrossed by pale road surfaces, and the dry salt lakes shone like glass.

Bill Angel grabbed her shoulder. ‘I know it’s hard,’ he shouted. ‘But Sanjai knew the rules. You got to play the hand you’ve been dealt, Paula. Godspeed.’

She turned and looked at him. His eyes were shining. This was, she realized, Bill’s apotheosis, what he lived for.

She thought of Chandran, and felt disgust at such bullshit.

She loosened her grip on the handhold –

– she would never have the guts to do this, to follow Sanjai –

– she leaned over the lip of the hatch, feeling the pole taking some of her weight –

– and she pushed herself out of the hatch, kicking against its sill as hard as she could.

She skimmed down the pole. She felt the brisk rip of the breakaway stitching. The hook, sliding roughly over the pole, made a noise like a roar. In a second she reached the pole’s end, and she fell away into the air.

It was like slamming into a wall. The breath was knocked out of her. And there was nothing beneath her feet for four miles. There were sharp tugs at her back as her pilot and drogue chutes opened automatically. She felt herself being hauled sideways and upwards.

She looked up.

She was already dropping away from the orbiter. She’d fallen under the port wing, and the orbiter was a huge delta shape, hanging in the sky only a few yards above her, the big silica tiles on its underside scarred and scorched. Black smoke trailed from the fat OMS engine pods on the tail.

Then it was gone, falling away into the huge air around her, trailing contrails. The white felt of its upper heatshield seemed to shine in the low morning sunlight.

Her main chute opened above her, and she fell into her harness with an impact that jarred the wind out of her.

She was no longer falling. She was just dangling here, and when she looked at her feet, she could see the thinly scattered towns of the Mojave rim, still miles below, obscured by mist. And there was the orbiter, a white delta shape, dropping like a stone, already beneath her. Skimming above the mist, it was the most vivid object in the world, receding rapidly.

She looked up. She could see four more chutes, opening out in the air.

Of Sanjai Chandran, of course, there was no sign.

She felt a sudden warmth between her legs, as her bladder released.

Gently, Lamb worked his pedals, and the control stick. He felt the crippled orbiter respond to his touch. He’d flown big aircraft, 747s and KC-135s. In them there was always a certain lag. But the orbiter was much more responsive, given its size more like a fighter than a liner; he could feel he was flying a big craft, but the responses to the controls were positive and crisp.

Today, though, Columbia was sluggish.

It was time for his own egress …

Things were calming down, though.

The master alarm hadn’t sounded for, oh, three or four minutes. And when he scanned his instruments, when he put it together, the data from his eight-ball and his CRT and his alpha-mach indicators told him that things weren’t too bad. He still had, in fact, enough energy and altitude for a feasible landing profile. Miles from the runway, maybe, but feasible, out on a dry lake somewhere.

He felt as if he’d spent half his life in front of these displays. Maybe he had, he thought. He felt at home here, in this busy, competent, glowing little cockpit.

Just a day at the office.

Lamb didn’t want to throw his life away. On the other hand, if Columbia was lost, that was the end of the space program, for sure.

Maybe it was time to rewrite the rule books, one last time.

He thought his way ahead, through the uncertainties of the next few minutes. He would have to manage his energy. He actually had to accelerate, to get to the ground with enough airspeed; by the time he got down to ten thousand feet he needed to have picked up to two hundred and ninety knots, plus or minus a few per cent.

He pitched Columbia’s nose down. His airspeed rose sharply.

‘Flight, Surgeon. I got six bail-outs. We lost one.’

‘… Six? Capcom –’

White said, ‘Columbia, Houston. What’s going on? You’re dropping out of fifteen thousand. Tom, you asshole, are you still on the flight deck?’

Fahy climbed away from her workstation and crossed to the capcom’s station. She plugged her headset into White’s loop. ‘Tom, this is Fahy. Get your ass out of there.’

‘You’re breaking up, Barbara. Anyway, since when has a Flight Director spoken direct on air-to-ground?’

There was a stir among the controllers.

A picture of the orbiter had come up on the big screen at the front of the FCR. It was hazy with distance and magnification. White contrails looped back from the wings’ trailing edges. And black smoke poured from the OMS engine pods.

Thirteen thousand feet.

Lamb looked down at the baked desert surface. It was flat, semi-infinite, like one huge runway. It was why Edwards had been sited out here in the first place.

Columbia flew over the straight black line of US 58.

This would make a hell of a tale to tell the boys over a couple of Baltics at Juanita’s, like the old days.

Fahy was still talking.

Patiently, he said, ‘If you’re going to be the capcom, give me my heading.’

‘Tom –’

‘Give me a heading, damn it.’

‘Uh, surface wind two zero zero. Seven knots. Set one zero niner niner. Tom –’

Now he was down to ten thousand feet, and that dip had earned him around three hundred knots extra velocity. Not so bad; he ought to be able to land within six or seven miles if he worked at it …

He got another master alarm. Main bus undervolt. That last power unit was giving out on him. But it wasn’t dead yet.

He punched the red button to kill the clamour.

There was no sound at the press stand, save the barking crackle of the PA’s air-to-ground loop.

The recovery convoy was racing off across the desert surface, towards the orbiter’s projected touchdown position, miles from the runway. They raised a dust cloud a thousand feet tall.

The orbiter was huge as it came in, impossibly ungainly. It was gliding down a steep entry path, as smooth as if it were mounted on invisible rails.

You could tell the bird was sick. Even Hadamard could see that, at a glance. There was some kind of black smoke billowing out of the fat engine pods at the orbiter’s tail. The pods themselves were badly charred and buckled. And there were yellow flames, actual flames, licking along the leading edge of that big tail fin. The public affairs officer said that was hydrazine, leaking out of ruptured power units over the orbiter’s hot surfaces.

But it wasn’t a disaster yet. In the distance Hadamard could see five billowing white parachutes, like thistledown, drifting down through the air.

Hadamard tried to think ahead. He was going to have trouble with that arrogant old asshole Tom Lamb, when he emerged from this, covered in fresh glory. He’d have to be kicked upstairs to somewhere he and his old Apollo-era buddies could be kept quiet, once the first PR burst was over …

Arrogant old asshole. Suddenly he pictured Tom Lamb sitting on the flight deck of that battered old orbiter, alone, struggling to bring his spacecraft home.

His calculation receded. Hadamard found he was holding his breath.

To increase his rate of descent, he pushed forward on his stick. The back end of the bird came up a little, and the attitude change increased his sink rate.

It was a steep descent: at seventeen degrees, five times as steep as the normal airliner approach, dropping three feet in every fifteen flown. He was pretty much hanging in the straps now, falling fast. He tried to keep his speed constant, by opening and closing the speed-brake with the throttle lever. He could feel the brake take hold, dragging at the air.

Way to his right, he could see where the runway had been painted on the bare desert surface, remote, useless. Beyond it was a group of drab, dun buildings: it was the Wherry housing area, where he’d once lived, when he’d flown F-104 chasers for the X-15s. But that had been in the middle of a different century, a hundred lifetimes ago.

Two thousand feet.

‘Beginning preflare.’ Using his hand controller and his speed-brake, he started to shallow his glideslope to two degrees.

Columbia responded, sluggishly, to the manoeuvre. But his speed was about right.

It was still possible. Even if the landing gear collapsed, even if the orbiter slid across half the Mojave on its belly. As long as he held her steady, through this final couple of thousand feet.

The baked desert surface fled beneath the prow of the orbiter, already shimmering with heat haze.

At a hundred and thirty-five feet, the orbiter bottomed out of its dip. He lifted the cover of the landing gear arming switch, and pressed it. At ninety feet, he pushed the switch.

He heard a clump beneath him, as the heavy gear dropped and locked into place.

‘Columbia, Houston. Gear down. We can see it, Tom.’

‘Gear down, rog. I’m going to take this damn thing right into the hangar, Marcus.’

‘Maybe we’ll dust it off a little first.’

Just a few more feet. Damn it, he could jump down from here and walk into Eddy.

‘Coming in a little steep, Tom.’

‘Yeah. Could do with a little prop wash right here.’

‘Hell,’ said White, ‘stop complaining. You never had to nurse a sick jet home to a carrier, in pitch darkness, in the middle of forty-foot Atlantic swells. Even a black-shoe surface Navy guy like you can handle this …’

Now for the final manoeuvre, a nose-up flare, to shed a little more velocity.

But now the master alarm sounded again. He didn’t have time to kill it.

According to the warning array, the last power unit had failed.

He jammed on the speed-brake, and shoved at his stick. If he could pitch her forward, get her nose flat – maybe there would be just a little hydraulic pressure left –

But the stick was loose in his hand, the throttle lever unresponsive.

The orbiter tipped back.

He heard an immense bang from the rear of the craft, as the tail section struck Earth.

Columbia was still travelling at more than two hundred knots.

The orbiter bounced forwards, tipping down as its aerosurfaces fluttered. He could feel the bounce, the longitudinal shudder of the airframe. And then came the stall. The orbiter had lost too much of its airspeed in that tail-end scrape to sustain lift.

The nose pointed to the ground.

Now – with the master alarm still crying in his ear, and the caution/warning array a constellation of red lights – the Mojave came up to meet him, exploding in unwelcome detail, more hostile than the surface of the Moon.

Barbara Fahy watched every freeze-framed step in the destruction of OV-102.

The second impact broke the orbiter’s spine. The big delta wings crumpled, sending thermal protection tiles spinning into the air. The crew compartment, the nose of the craft, emerged from the impact apparently undamaged, trailing umbilical wires torn from the payload bay. Then it toppled over and drove itself nose-first into the desert. It broke apart, into shapeless, unrecognizable fragments. The tail section cracked open – perhaps that was the rupture of the helium pressurization tanks – and Fahy could see the hulks of the three big main engines come bouncing out of the expanding cloud of debris, still attached to their load-bearing structures and trailing feed pipes and cables.

The black smoke billowing from the tail section was suddenly brightened by reddish-orange flames, as the residual RCS fuel there burned.

The orbiter’s drag chute billowed out of its container in the tail. Briefly it flared to its full expanse, a half-globe of red, white and blue; then it crumpled, and fell to the dust, irrelevant.

White thought of Tom Lamb. It was like a vision, blinding him.

… Tom came loping out of a a shallow crater, towards White. Tom looked like a human-shaped beach ball, his suit brilliant white against the black sky, bouncing happily over the sandy surface of the Moon. Tom had one glove up over his chest, obscuring the tubes which connected his backpack. to his oxygen and water inlets. His white oversuit was covered in dust splashes. His gold sun visor was up, and inside his white helmet White could see Tom’s face, with its four-day growth of beard …

Damn, damn. It was as if it was yesterday. That was how he was going to remember his friend, he knew; as he was during those three sun-drenched days they’d had together on the Moon, both of them feeling light as feathers: the most vivid moments of his life, three days that had shaped his whole damn existence.

He turned away from the FCR screens.

The morning California sunlight was bright. It illuminated the expanding cloud of dust and smoke, turning it into a kind of three-dimensional, kinetic sculpture of light, set against the remote hills surrounding the dry lake beds.

Hadamard, beyond calculation, knew he would spend the rest of his life with this brief sequence of images, watching them over and again.

Jiang gazed at the glistening curvature of Earth: the wrinkled oceans, the shadow-casting clouds stacked tall over the equator. Outside the cabin, all the way to infinity, there was no air; just silence. She felt small, fragile, barely protected by the thin skin of the xiaohao.

Where she passed, she relayed revolutionary messages, reading from a book she had carried in a pocket of her pressure suit. ‘Warm greetings from space,’ she said. ‘Everything that is good in me I owe to our Communist Party and the Helmsman of the Country. This date is one on which mankind’s most cherished dreams come true, and also marks the triumph of Chinese science and technology …’

The words were so familiar to her, homilies from classes in politics, as to be almost meaningless. And yet, here, alone in the blackness of space, with the blue light of Earth illuminating the pages of the book, she felt filled with a deep, unfocused nostalgia. She felt growing within her an abiding attachment for her huge country, for the billion-strong horde of her countrymen: the brash entrepreneurial class in the bustling coastal cities, the peasants still scratching at their fields as they had done for five millennia. She was of them, and so of the Party which, after seven decades, still ruled; she would, she knew, never be anything more or less than that.

But now the ground controllers were telling her, in clipped sentences, of some disaster involving the American Space Shuttle. They sounded jubilant, she thought. They had her intone words of sympathy, of fellowship, broadcast from orbit.

The truth was she felt little concern, for whatever might have befallen the American astronauts. This was her moment; nothing could diminish that.

Though she knew she would be under pressure to become an ambassador for the space program, for the Party, and for China, Jiang intended to battle to stay within the unfolding program itself. The Helmsman had stated that a Chinese astronaut would walk on the surface of the Moon before 2019: the seventieth anniversary of Mao’s proclamation of the People’s Republic. Jiang felt her grin tighten as she thought about that. It would be a remarkable achievement, an affirmation that China would, after all, awake from her centuries-long slumber and become the dominant world power in the new millennium.

And it was only fifteen years away.

Jiang would still be less than fifty. Americans and Russians had flown at much greater ages than that …

And so she read the simple words of soldier and Party leaders, as she sailed over the skin of Earth.

Paula Benacerraf, suspended, could hear sounds, drifting up to her from the huge, empty ground below. Her own breathing was loud in her ears.

This was the end of the US space program, and the end of her own career.

Earth was claiming her. For the rest of her life.

She could see her future, mapped out. Her destiny was no more than to be a survivor of Columbia, and somebody’s mother, somebody’s grandmother, for the rest of her life.

She’d never get back to space again. She’d never again drift in all that light, never see the lights of her spacecraft as it drifted in its own orbit beneath her.

Like hell, she thought. There has to be an option.

She tucked up her legs, keeping away from the Earth as long as she could. But the impact in the dirt, when it came, was hard.

BOOK TWO Low Earth Orbit A.D. 2004 – A.D. 2008

‘What did you think you were doing, Rosenberg?’

Marcia Delbruck, Rosenberg’s project boss, was pacing around her office, formidable in her Berkeley sweatshirt and frizzed-up hair; she had a copy of Jackie Benacerraf’s life-on-Titan article loaded on her big wall-mounted softscreen. ‘You’ve made a joke of us all, of the whole project.’

‘That’s ridiculous, Marcia.’

‘You let this woman Jackie Benacerraf get to you. You just can’t handle women, can you, Rosenberg?’

Actually, he thought, no. But he wasn’t going to sit here and take this. ‘All I did was speculate a little.’

‘About life on Titan? Jesus Christ. Do you know how much damage that kind of crap can do?’

‘No. No, I don’t really see what damage that kind of crap can do. I know it’s bad science to go shooting my mouth off about tentative hypotheses before –’

‘It’s not the science. It’s the PR. Don’t you understand any of this?’ She sat down behind her desk. ‘Isaac, you have to look at the situation we’re in. Think back to the past. Look at 1964, when the first Mariner reached Mars. It was run out of JPL, right here –’

‘What has some forty-year-old probe got to do with anything?’

‘Lessons of history, Rosenberg. Back then, NASA was already thinking about how to follow on from Apollo. Mars would have been the next logical step, right? Move onward and outward, human expansion into the Solar System.

‘But Mariner found craters, like the Moon’s. They’d directed the craft over an area where they were expecting canals, for God’s sake.

‘All of a sudden, there was no point going to Mars after all, because there was nothing there except another sterile, irradiated ball of rock. You could say that handful of pictures, from that first Mariner, turned the history of space exploration. If Mars had been worth going to, we’d be there by now. Instead, NASA was just wound down.’

‘I know about the disappointment,’ he said icily. ‘I read Bradbury, and Clarke, and Heinlein. I can imagine how it was.’

‘NASA learned its corporate lesson, slowly and painfully.’ She thumped the desk with her closed fist to emphasize her words. ‘Look how carefully they handled the story of the organic materials they found in the Martian meteorite …’

‘Careful, yeah. But so what? They still haven’t flown a Mars sample-return mission to confirm –’

‘It’s not the point, Rosenberg,’ she snapped. ‘You don’t promise what you don’t deliver. You don’t yap to the media about finding life on Titan.’

‘All I talked about was the preliminary results, and what they might mean. You can hear the same stuff in the canteen here any day of the week.’

She tapped the clipping on her screen. ‘This isn’t the JPL canteen, Rosenberg.’

‘Anyway, what does NASA have to do with it? JPL’s an arm of Caltech; it’s organizationally independent –’

‘Don’t be smart, Rosenberg. Who the hell do you think you are? Maybe it’s escaped your notice, but you’re just one of a team here.’

The team lecture, he thought with dread. ‘I know.’ Rosenberg pushed the heels of his hands into his eye sockets. ‘I know about the line, and the matrix management structure, and my office, division, section, group and subgroup. I know about the organization charts and documentation trees.’ It was true. He did know all about that; he’d had to learn. An education in JPL’s peculiar politics was like a return to grade school biology, learning about kingdoms and phyla and classes.