Titan

Anyhow, then she’d transferred to NASA. She’d worked as a payload controller in Mission Control, and then, at her third attempt, made it into the Astronaut Office. She’d paid her dues as an ascan, and finally been attached to a Shuttle flight – STS – 141, Atlantis – and come flying up here, to Station, for a six-month vigil.

It turned out to be a question of just surviving in this shack of a Service Module, boring a hole in the sky for month after month. Russian and American crews, brought up by Shuttle, had been rotating up here on six-month shifts, struggling to do some real research in these primitive conditions, their main purpose to keep this rump of the Station alive with basic maintenance and housekeeping.

Even so, at first she’d been thrilled just to be in space, all these years after those Illinois dreams. And as her relationship with Siobhan Libet had matured, the experience had come to seem magical.

Then, after a few weeks of circling the Earth, she’d got oddly frustrated. She got bored with the stodgy Russian food and with the daily regime of exercise and dull maintenance. The Station blocks were so small compared to the huge spaces out there; it seemed absurd to be so confined, to huddle up against the warm skin of Earth like this.

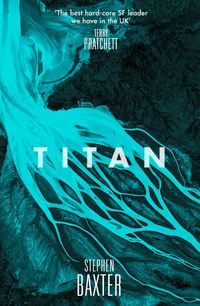

Damn it, she wanted to go somewhere. Such as Titan, where those hairies at JPL thought they’d found life signs … But nobody was offering a ride.

It wasn’t really the great tragic downfall in human destiny that was bothering her, she admitted. It was her own screwed-up career.

Mott was thirty-four years old, and she wasn’t given to morbid late-night thoughts like these. She started to feel cold, and, suddenly, terribly lonely. Staying up all night no longer seemed such a great idea.

She pulled herself back through to the Service Module.

The interior of Station was cramped and crowded. The walls were lined with instrument panels, wall mounts for air-scrubbing lithium chlorate canisters, other equipment. These two modules had been serving alone as the core of the Space Station for too many years now, and as parts had worn out replacements had been flown up and crudely bolted in place, and new experiments had been brought up here and fixed to whatever wall space was available. As a result the clutter was prodigious; cables and pipes and lagged ducts trailed everywhere, and there was a sour smell, the stink of people locked up in a small space for too long.

She pressurized the water tank, and fired the spigot. A globe of water came shimmering through the air towards her face, the lights of the module sharply reflected in its meniscus. She opened her mouth and let the water drift in; when she closed her mouth around the globule it was as if the water exploded over her palate, crisp and cold.

If she couldn’t get back into space, she’d never in her life be able to take a drink like that again, she thought. Returning to Earth was going to be like a little death.

Her sleeping compartment was a space like a broom cupboard, with its own window, cluttered with bits of gear and clothing. Her sleeping bag was fixed straight up and down against the wall of the module, and she had to crane her neck to see out of her window, at the slice of Earth which drifted past there. With the Earthlight, and the subdued floods of the compartment, the Service Module was pretty bright, and the pumps and ventilation fans kept up a continual rattle. It was like being in the guts of some huge machine.

She pulled herself deeper into her sleeping bag, which soon became warm enough for her to be able to forget the endless vacuum a few inches away from her face, beyond the module’s cladded hull.

After an unmeasured time, she felt a hand stroking her back. She turned in her bag. Siobhan, naked, her hair floating around her face in a big burst of colour, was silhouetted against the cabin lights.

Mott smiled and reached out. She brushed Libet’s hair back, revealing her fine, high brow. ‘You look like Barbarella,’ she said.

‘In your dreams. Are you going to let me in?’

The sleeping bags were too small for two people. But they’d found a way of zipping their two bags together. It was cold, the opening at the top liable to let in draughts, but their bodies would soon build up a layer of warm air around them.

‘Anyhow,’ Mott said, ‘I thought you wanted to sleep.’

‘I did. I do. But I guess I can spend the rest of my life asleep. Down there, at the bottom of the gravity well. This seems too good an opportunity to pass up. The last time anyone will be having sex in space, for a long, long time …’

Mott clung to Libet.

Libet stroked her back. ‘Who was the first, do you think? The first orgasm in space.’

Mott snorted. ‘Yuri Gagarin, probably. Or one of those Mercury assholes fulfilling a bet. Maybe even old Al Shepard managed it.’

‘Oh, come on. He only had fifteen minutes. Even Big Al couldn’t have done it in that time. Anyway, those Mercury suits were hard to open up.’

‘Fifteen minutes. Well, we haven’t got much longer.’

Libet’s hand, warm now, moved over Mott’s stomach. ‘From first to last.’

‘From first to last,’ Mott said, and she closed her eyes.

She was woken by a buzzer alarm, at 4 a.m. It felt as if she hadn’t slept at all.

They prepared a hasty meal: tinned fish and potatoes, tubes of soft cheese, and a vegetable puree that had to be reconstituted with hot water. The rations were Russian standard, and, as usual, tasted salty and heavy with butter and cream to Mott. She drank sweet coffee from a plastic bag with a roll-out spout. She tried not to drink too much; she was going to be in her pressure suit for a long time.

Libet went down to the Soyuz to run a final check, and Mott got herself dressed in her stiff Russian-design pressure suit.

Libet suited up in her turn, and they pressurized each other’s suits, making sure they were airtight. Then Mott tested her pressure-release valve, a large knob on the suit’s chest panel.

She pocketed some souvenirs: her Swiss army knife, photographs.

By six a.m. they were both ready to leave.

A TV camera was mounted in one corner of the Service Module, all but concealed amid the equipment lockers and cables there. The camera was mute, no red light showing. It looked as if nobody wanted to record these last acts of the American manned space program, two unhappy astronauts clambering into Russian pressure suits.

Mott led the way for the last time out of the Service Module and through the FGB towards Soyuz. Behind her, Libet killed the lights in the Service Module.

The waiting Soyuz was stuck on the side of the FGB, nose-first.

She could see through blister windows in the FGB that the body of the ship was a light blue-green, an oddly beautiful, Earthlike colour. The Soyuz looked something like a pepperpot, a bug-like shape nine feet across. Two matte-black solar panels jutted from its rounded flanks, like unfolded wings, and a parabolic antenna was held away from the ship, on a light gantry. Soyuz was basically a Gemini-era craft, still flying in this first decade of a new millennium. And today, Mott and Libet were going to have to ride Soyuz home.

The Soyuz was strictly an assured crew return vehicle, in the nomenclature of the Station project, a simple mechanism for the crew to make it back to Earth in case the Shuttle, the primary crew ferry, couldn’t make it in some emergency. The Mission Controllers, down in Houston and Kalinin, had decided that the Columbia incident and subsequent Shuttle grounding constituted just such an emergency.

The Soyuz’s Orbital Module was a ball stuck to the craft’s front end, lined with lockers, just big enough for one person to stretch out. It would be discarded to burn up during the reentry, so Mott and Libet had packed it full of garbage. Now Mott had to struggle through discarded food containers and clothing and equipment wrappers, many of them floating around, to get through to the Descent Module. It was like struggling through a surreal blizzard.

The Descent Module, the headlight-shaped compartment in which they would make their return to Earth, was laid out superficially like an Apollo Command Module, with three lumpy-looking moulded couches set out in a fan formation, their lower halves touching. There were two circular windows, facing out beside the two outer seats. Big electronics racks filled up the space beneath the couches, and a large moulded compartment on one wall contained the main parachute. Mott slid herself in, feet-first, wriggling until she could feel the contours of the right-hand seat under her. The seat was too short for her, and compressed her at her shoulders and calves.

There was a small, circular pane of glass at Mott’s right elbow. She peered out of this now, trying to lose herself in the view of blue Earth.

After a few minutes, Libet floated headfirst into the compartment. She pushed the last of the garbage back into the Orbital Module, and dogged the hatch closed. Then she somersaulted neatly and slid into the center couch, compressing Mott against the wall; their lower legs were in contact, and there was no space for her to move away.

The two of them began to work through a pre-entry checklist.

At a little after 9.00 a.m., it was time for the undocking. The clamps that held the craft together were released. A spring connector pushed at the Soyuz; there was a gentle thump, and the Soyuz drifted gently away from Station.

For an hour, Libet used the Soyuz’s crude hand controller to fly the ferry around Station. Mott was supposed to take a final set of photographs of the abandoned Station before the descent. She had to sit up out of her couch and wedge herself in the small porthole to get the shots.

Mott could see the whole assembly, floating against a curving horizon, with the meniscus of clouds masking the ground below. In the light of Earth, Station was brightly illuminated, a T-shaped mélange of greys, greens, whites. It looked quite delicate and beautiful.

The unfinished Station looked pretty much like Mir had, in an early stage of its construction, she supposed. The two main blocks, both orbited by Russian Protons, were the Service Module, a three-crew habitat based closely on the Mir’s base block, and the FGB, based on the Mir’s Kvant supply module. The two modules were squat cylinders, docked end-to-end, punctuated with small round portholes, and coated with thermal insulation, a powdery cloth that was peppered by fist-sized meteorite scars. Small solar panels stretched out to either side of each module, like battered wings, with big charcoal-black cells and fat wires fixed in place with crude blobs of solder. A Progress unmanned ferry, another Soyuz variant, was docked to the Service Module’s aft port, on the other side from the FGB.

On the forward port of the FGB was docked the main American contribution to date, a small module called Resource Node 1, which had provided storage space for supplies and equipment, berthing ports, a Shuttle docking port, and attachment points for more modules and the Station’s large truss: a gantry that would have stretched all of three hundred and sixty feet long, with the huge photovoltaic arrays stretching out to either side.

But the assembly hadn’t got that far. Only the first piece of the truss, a small complex element called Z1, had been hauled up by Endeavour and fitted to the top of Node 1. Future flights would have brought up more truss segments, the comparatively luxurious US habitation module, and the multinational lab modules, sleek, modern-looking cylinders the size of railway carriages which would have clustered closely around the Resource Nodes.

In fact, the completed Station would have looked, she thought, like a collision between the twenty-first century and the twentieth – the modern American design, components and concepts inherited from the billions invested in abortive Space Station studies since 1984, forced together with a second-generation Russian Mir.

It was all such a waste.

If they’d flown up one more mission, STS – 94, at least they’d have had a serious science facility up here. STS – 94 would have been the fifth US assembly flight; it would have delivered the first US lab module, complete with thirteen racks of science equipment, life support, maintenance and control gear. And they would have been able to do some real work up here, instead of the small-scale make-work experiments they’d had to run: monitoring herself for drug metabolism by taking saliva samples, checking for radiation health with miniature dosimeters strapped to her body, checking her respiration during exercises on the treadmill, investigating the relationship between bone density and venous pressure by wearing dumb little tourniquets around her ankle …

STS – 94 had been scheduled for early 1999. Delays, funding cuts and problems with the early Station modules and operations had pushed back its launch five years. And now, it would never fly, and Station would never be completed.

Soyuz was passing over South America. Mott could see the pale fresh water of the Amazon, the current so strong it had still failed to mingle, hundreds of miles off shore, with the dark salt ocean.

The retro rockets fired with a solid thump. For the first time in four months a sensation of weight returned to Mott, and she was pressed into her seat.

When the burn was done, the feeling of weight disappeared. But now the Soyuz was no longer in a free orbit but was falling rapidly towards Earth.

There was something wrong with her eyes. She lifted up her hand, and found salt water, big thick drops of it, welling over her cheeks.

She was crying. Damn it.

‘Dabro pazhalavat,’ Siobhan Libet said softly. ‘Welcome home.’

Through her window now she could see nothing but blackness.

Jake Hadamard called Benacerraf. She was in her room in the Astronaut Office at JSC, poring over a technical reconstruction of the multiple failures that had destroyed Columbia’s APUs.

‘Hi. I’m here at JSC. Look, I need to talk to you. Can you get away?’

When she heard the Administrator’s dry voice, she felt pressure piling up on top of her, a force as tangible as the deceleration which had dragged her down into her canvas seat, during that last reentry from space. What now? ‘Do you want me to come over?’

‘No. Let’s get out of here, for a couple of hours. Meet me at the Public Affairs Office parking lot …’

It was a bizarre request, but Benacerraf sure as hell needed a break. She pulled on a light white sweatshirt and a broad-brimmed hat, and went out to the elevator.

It was three p.m. on a hot July afternoon.

She emerged into a Mediterranean flat heat – after the dry, cold air-conditioning it was like walking into a wall of dampness – and she was immersed in the steady chirp of crickets. She walked across the courtyard of the JSC campus towards Second Street, which led to the main gate.

The blocky black and white buildings of JSC were scattered over the landscaped lawns like children’s blocks, with big black nursery-style identifying numbers on their sides. Between the buildings were Chinese tallow trees and tough, thick-bladed, glowing green Texas grass; sprinklers seemed to work all the time, hissing peacefully, a sound that always reminded her of a Joni Mitchell album she’d gotten too fond of in her teenage years.

But JSC was showing its age. Most of the buildings were more than forty years old; despite the boldness of the chunky 1960s style the buildings themselves were visibly ageing, and after decades of budget cutbacks looked shabby: the concrete stained, the paint peeling. On her first visits here she’d been struck by the narrow corridors and gloomy ceiling tiles of many of the older buildings; it was more like some beat-up welfare agency than the core of a space program.

As he’d promised, Jake Hadamard was waiting for her at the car park close to the PAO. The lot was pretty full: old hands said wearily that there hadn’t been so much press interest in NASA since Challenger.

They piled into Hadamard’s car. It was a small ’oo Dodge. He drove out through the security barrier, down Second Street, and towards NASA Road One, the public highway. Hadamard grinned. ‘I have a limousine here I can use, with a driver,’ he said. ‘But my job is kind of diffuse. I like to be able to do things personally from time to time.’

Benacerraf said, ‘So, you drive for release.’

‘I guess.’

To the right of Second Street, which ran through the heart of JSC, was the Center’s rocket garden. There was a Little Joe – a test rocket for Apollo – and a Mercury-Redstone, looking absurdly small and delicate. The black-and-white-striped Redstone booster was just a simple tube, so slim the Mercury capsule’s heat shield overhung it. The Redstone was upright but braced against wind damage with wires; it looked, Benacerraf thought, as if it had been tied to the Earth, Gulliver-style. And, just before the big stone ‘Lyndon B Johnson Space Center’ entry sign at NASA One, they passed, on the right, the Big S itself: a Saturn V moon rocket, complete with Apollo, broken into pieces and lying on its side.

A small group of tourists, evidently bussed over from the visitors’ center, Space Center Houston, hung about in front of the Redstone. They wore shorts and baseball caps, and their bare skin was coated with image-tattoos, and they looked up at the Redstone with baffled incomprehension.

But then, Benacerraf thought, it was already more than four decades since Alan Shepard’s first sub-orbital lob in a tin can like this. Two generations. No wonder these young bedecked visitors looked on these crude Cold War relics with bemusement.

Hadamard pulled out onto NASA Road One, and headed west. As he drove he sat upright, his grey-blond hair close-cropped, his hands resting confidently on the wheel as the car’s internal processor took them smoothly through the traffic.

They cut south down West NASA Boulevard, and pulled off the road and into a park. Hadamard drove into a parking area. The lot was empty save for a big yellow school bus.

‘Let’s walk,’ Hadamard said.

They got out of the car.

The park was wide, flat, tree-lined, green. The air was still, silent, save for the sharp-edged rustle of crickets, and the distant voices of a bunch of children, presumably decanted from the bus. Benacerraf could see the kids in the middle distance, running back and forth, some kind of sports day.

Hadamard, wearing neat dark sunglasses and a NASA baseball cap, led the way across the field.

Benacerraf took a big breath of air, and swung her arms around in the empty space.

Hadamard grinned at her, and his shades cast dazzling highlights. ‘Feels like coming home, huh.’

‘You bet.’ She thought about it. ‘You know, I don’t think I’ve walked on grass, except for taking short cuts across the JSC campus, since I got back from orbit.’

‘You should get out more.’ He scuffed at the grass with his patent leather shoes. ‘This is where we belong, after all. Here, on Earth, where we’ve spent four billion years adapting to the weather.’

‘So you don’t think we ought to be travelling in space.’

He shrugged, and patted at his belly. ‘Not in this kind of design. A big heavy bag of water. Spacecraft are mostly plumbing, after all … Humans don’t belong up there.’

‘Oh, come on.’

‘Well, they don’t. You should hear what the scientists say to me. Every time someone sneezes on Station, a microgravity protein growth experiment is wrecked.’

Benacerraf said, ‘You’re repeating the criticisms that are coming out in the Commission hearings. You know, it’s like 1967 over again, after the Apollo fire.’

‘Yes, but back then they managed to restrict the inquiries afterward to a NASA internal investigation. And that meant they could keep most of the recommendations technical rather than managerial.’

Benacerraf grunted. ‘Neat trick.’

Hadamard laughed. ‘Well, the Administrator back then was a wily old fox who knew how to play those guys up on the Hill. But I’m no Jim Webb. After Challenger we had a Presidential Commission, just like the one that we’re facing now.’

They reached the woods, and the seagull-like cries of the children receded.

Eventually they came to a glade. A monument stood on a little square of bark-covered ground, enclosed by the trees, and the dappled sunlight reflected from its upper surface. It was box-like, waist high, and constructed of some kind of black granite.

It was peaceful here. She wondered what the hell Hadamard wanted.

Jake Hadamard took a deep breath, pulled off his sunglasses, and looked at Benacerraf. ‘Paula, do you know where you are? When I first came to work at NASA, I was struck by the –’ he hesitated ‘– the invisibility of the Challenger incident. I mean, there are plenty of monuments around JSC to the great triumphs of the past, like Apollo 11. Pictures on the walls, the flight directors’ retirement plaques, Mission Control in Building 30 restored 1960s style as a national monument, for God’s sake.

‘But Challenger might never have happened.

‘It’s the same if you go around the Visitors’ Center. You have your Lego exhibits and your Station displays and your pig-iron toy Shuttles in the playground, and that inspirational music playing on a tape loop all the time. But again, Challenger might never have happened.

‘Outside NASA, it’s different. For the rest of us, Challenger was one of the defining moments of the 1980s. The moment when a dream died.’

He said us. Benacerraf found the word startling; she studied Hadamard with new interest.

He said, ‘Look around Houston and Clear Lake. You have Challenger malls and car lots and drug stores … And look at this monument.’

Benacerraf bent to see. The monument’s white lettering had weathered badly, but she could still make out the Harris County shield inset on the front, and, on the top, the mission patch for Challenger’s final flight: against a Stars-and-Stripes background, the doomed orbiter flying around Earth, with those seven too-familiar names around the rim: McNair, Onizuka, Resnik, Scobee, Smith, Jarvis, McAuliffe.

‘We’re in the Challenger Seven Memorial Park,’ Hadamard said. ‘You see, what’s interesting to me is that this little monument wasn’t raised by NASA, but by the local people.’

‘I don’t see what you’re getting at, Jake.’

‘I’m trying to understand how, over two decades, these NASA people have come to terms with the Challenger thing. Because I need to learn how to size up the recommendations I’m getting from you for the way forward after Columbia.’

Benacerraf said, ‘You want to know if you can trust us.’

He didn’t smile.

‘NASA people didn’t launch that Chinese girl into orbit,’ she said. ‘And that’s the source of the pressure on you to come up with some way to keep flying.’

‘Is it?’

Benacerraf decided to probe. ‘You know, now that I’m getting to know you, you aren’t what I expected.’

He smiled. ‘Not just a bean counter, a politico on the make? Paula, I am both of those things. I’m not going to deny it, and I’m not ashamed of either of them. We need politicos and bean counters to make our world go round. But –’

‘What?’

‘I wasn’t born an accountant. I was seventeen when Apollo II landed. I painted my room black with stars, and had a big Moon map on the ceiling –’

‘You?’

‘Sure.’

‘And you’re the NASA Administrator.’

He shrugged. ‘I’m the Administrator who was on watch when Columbia turned into a footprint on that salt lake.

‘I’m going through hell, frankly, facing that White House Commission. Phil Gamble is getting the whipping in the media, but the Commission are just beating up on me. And then there’s the pressure from the Air Force. You know, over the years the Air Force has made some big mistakes chasing manned spaceflight. They wasted a lot of money on projects that didn’t come to fruition: the X – 20 spaceplane, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory … In the 1970s they were pushed into relying on the Shuttle as their sole launch vehicle. That single space policy mistake cost them twenty billion dollars, they tell me, in today’s money. And now we got Columbia, and the fleet is grounded again. You can bet that if Shuttle never flies again, there will be plenty in USAF who won’t shed a tear.