Titan

‘Then,’ she snapped, ‘you know that you occupy one space in that organization, one little bitty square, and that’s where you should damn well stay. Leave the press to the PR people; they know how to handle it right … Look, Rosenberg, you have to come to some kind of accommodation with me. I’m telling you there’s no other way to run a major project like a deep space mission except with a tight, lean organization like ours. And it works. As long as we all work within it.’

‘Come on, Marcia. We shouldn’t be talking about organizational forms, for God’s sake. At the very least we’ve got evidence of a new kind of biochemistry, something completely new, out on the surface of that moon. We should be talking about the data, the results. About going back, a sample-return mission –’

‘Going back?’ She laughed. ‘Don’t you follow the news, Rosenberg? The Space Shuttle just crashed. Nobody knows what the hell the future is for NASA. If it has one at all.’

‘But we have to go back to Titan.’

‘Why?’

He couldn’t see why she would even pose the question. ‘Because there’s so much more to learn.’

‘Let me give you some advice, Rosenberg,’ she said. ‘We aren’t going back to Titan. Not in my lifetime, or yours. No matter what Huygens has found. Just as we aren’t going back to Venus, or Mercury, or Neptune. We’ll be lucky to shoot off a few more probes to Mars. Get used to the fact. And the way to do that is to get a life. I understand you, Rosenberg. Better than you think I do. Probably better than you understand yourself. Titan is always going to be out there. What’s the rush? What you’re talking about is yourself. What you mean is that you want to discover it all, before you die. That’s what motivates you. You can’t bear the thought of the universe going on without you, its events unfolding without your invaluable brain still being around to process them. Right?’

This sudden descent into personal analysis startled him; he had no idea what to say.

She sat back. ‘Look. I know you’re a good worker; I know we need people like you, who can think out of the box. But I don’t need you shooting your mouth off to the press. It’s not three months since Columbia came down. We’re trying to preserve Cassini, the last of the great JPL probes; you must know we haven’t secured funding for the extended mission yet. If you attract enough hostility, you could get us shut down, future projects killed …’

Slowly, he realized that she meant it. She was expressing a genuine fear: that if space scientists attracted too much attention – if they sounded as if they weren’t being ‘responsible’, as if they were shooting for the Moon again – then they’d be closed down.

In the first decade of a new millennium, a sense of wonder was dangerous.

Discreetly he checked his watch. He was meeting Paula Benacerraf later today. Maybe he could find some new way forward, with her. And …

But Delbruck was still talking at him. ‘Have you got it, Rosenberg? Have you?’

Rosenberg came to pick Benacerraf up, in person, from LAX. She shook Rosenberg’s offered hand, and climbed into the car.

Rosenberg swung through Glendale and then turned north on Linda Vista to go past the Rose Bowl. For a few miles they drove in silence, except for the rattling of the car, which was a clunker.

Rosenberg, half Benacerraf’s age, seemed almost shy.

Rosenberg’s driving was erratic – he took it at speed, with not much room for error – and he was a little wild-eyed, as if he’d been missing out on sleep. Probably he had; he seemed the type.

JPL wasn’t NASA, strictly speaking. She’d never been out here before, but she’d heard from insiders that JPL’s spirit of independence – and its campus-like atmosphere – were important to it, and notorious in the rest of the Agency.

So maybe she shouldn’t have been surprised to have been summoned out here like this, by Isaac Rosenberg, a skinny guy in his mid-twenties with glasses, bad skin, and thinning hair tied back in a fashion that had died out, to her knowledge, thirty years ago.

‘This seems a way to go,’ she remarked after a while. ‘We’re a long way out of Pasadena.’

‘Yeah,’ Rosenberg said. ‘Well, they used to test rockets here. Hence “Jet Propulsion Laboratory” …’ He kept talking; it seemed to make him feel more comfortable. ‘The history’s kind of interesting. It all started with a low-budget bunch of guys working out of Caltech, flying their rockets out of the Arroyo Seco, before the Second World War. They had huts of frame and corrugated metal, unheated and draughty, so crammed with rocket plumbing there was no room for a desk … And then a sprawling, expensive suburb got built all around them.

‘After the war the lab became an eyesore, and the residents in Flintridge and Altadena and La Canada started to complain about the static motor tests, and the flashing red lights at night.’

‘Red lights?’

He grinned. ‘It was missile test crews heading off for White Sands. But the rumours were that the lights were ambulances taking out bodies of workers killed in rocket tests.’

She smiled. ‘Are you sure they were just test crews? Or –’

‘Or maybe there’s been a cover-up.’ He whistled a snatch of the classic X-Files theme, and they both laughed. ‘I used to love that show,’ he said. ‘But I never got over the ice-dance version.’

He entered La Canada, an upper-middle-class suburb, lawns and children and ranch-style, white-painted houses, and turned a corner, and there was JPL. The lab was hemmed into a cramped and smoggy site, roughly triangular, bounded by the San Gabriel Mountains, the Arroyo Seco, and the neat homes of La Canada.

Rosenberg swung the car off the road.

There was a guard at the campus entrance; he waved them into a lot.

Rosenberg walked her through visitor control, and offered to show her around the campus.

They walked slowly down a central mall that was adorned with a fountain. The mall stretched from the gate into the main working area of the laboratory. Office buildings filled the Arroyo; some of them were drab, military-standard boxy structures, but there was also a tower of steel and glass, on the north side of the mall, and an auditorium on the south.

Crammed in here, it was evident that the only way JPL had been able to build was up.

Rosenberg said, ‘That’s the von Karman auditorium. A lot of great news conferences and public events took place in there: the first pictures from Mars, the Voyager pictures of Jupiter and Saturn –’

‘What about the glass tower?’

‘Building 180, for the administrators. Can’t you tell? Nine storeys of marble and glass sheathing.’ He pointed. ‘Executive suites on the top floor. I expect you’ll be up there later to meet the Director.’

The current JPL Director was a retired Air Force general. ‘Maybe,’ said Benacerraf. ‘It’s not on my schedule.’ And besides, she’d had enough Air Force in her face recently. ‘I wasn’t expecting quite so much landscaping.’

‘Yeah, but it’s limited to the public areas. I always think the place looks like a junior college that ran out of money half way through a building program. When the trees and flower pots appeared, the old-timers say, they knew it was all over for the organization. Landscaping is a sure sign of institutional decadence. You come to JPL to do the final far-out things, not for pot plants …’

She watched him. ‘You love the place, don’t you?’

He looked briefly embarrassed; it was clear he’d rather be talking at her than be analysed. ‘Hell, I don’t know. I like what’s been achieved here, I guess. Ms Benacerraf –’

‘Paula.’

He looked confused, comically. ‘Call me Rosenberg. But things are changing now. It seems to me I’m living through the long, drawn-out consequences of massive policy mistakes made long before I was born. And that makes me angry.’

‘Is that why you asked me to come out here?’

‘Kind of.’

He guided her into one of the buildings. He led her through corridors littered with computer terminals, storage media and printouts; there were close-up Ranger photographs of the Moon’s surface, casually framed and stuck on the walls.

But those Moon photographs were all of forty years old: just historic curios, as meaningless now as a Victorian naturalist’s collection of dead, pinned insects. There was an air of age, of decay about the place, she thought; the narrow corridors with their ceiling tiles were redolent of the corporate buildings of the middle of the last century.

JPL was showing its age. It had become a place of the past, not the future.

How sad.

He led her out back of the campus buildings, to a dusty area compressed against the Arroyo and the mountain. Here, the roughhewn character of the original 1940s laboratory remained: a huddle of two- and three-storey Army base buildings – now more than sixty years old – in standard-issue military paintwork.

Rosenberg pointed. ‘Even by the end of the war there were still only about a hundred workers here. Just lashed-up structures of corrugated metal, redwood tie and stone. See over there? They had a string of test pits dug into the side of the hill, lined with railroad ties. They called it the gulch. You had to drive to the site over a bumpy road that washed out in the rainy season … It was as crude as hell. And yet, the exploration of the Solar System started right here.’

‘Why are you showing me all this, Rosenberg?’

He took off his glasses and polished them on a corner of his T-shirt. ‘Because it’s all over for JPL,’ he said. ‘For decades, as far back as Apollo, NASA has starved JPL and space science to pay for Man-In-Space. And now – hell, I presume you’ve heard the scuttlebutt. They’re even going to close down the Deep Space Network. They’re already talking about mothballing the Hubble. And Goldstone will be turned over to the USAF for some kind of navel-searching reconnaissance work.’

‘It’s all politics, Rosenberg,’ Benacerraf said gently. ‘You have to understand. The White House has to respond to pressure from the likes of Congressman Maclachlan. They have to appear in control of their space budgets. So if they are throwing money at new launch vehicles to replace Shuttle, they have to cut somewhere else …’

‘But when we all calm down from our fright about the Chinese, they’ll just cut the launcher budgets anyhow, and we’ll be left with nothing. Paula, when it’s gone, it’s gone. The signals coming in from the last probes – the Voyagers, Galileo, Cassini – will fall on a deaf world. Think about that. And as for JPL, those sharks in the USAF have been waiting for something like Columbia, waiting for NASA to weaken. It’s as if they’re taking revenge. They’re going to turn us into a DoD-dedicated laboratory. The NASA links will be severed, and we’ll lose the space work, and all of our research will be classified, for good and all. The Pentagon calls it weaponization.’

‘Rosenberg –’

He looked into the sky. ‘Paula, in another decade, the planets are going to be no more than what they were, before 1960: just lights in the sky. The space program is over at last, killed by NASA and the USAF and the aerospace companies …’

No, she thought automatically. It’s more complex than that. It always was. The space program is a major national investment. It’s been shaped from the beginning by political, economic, technical factors, beyond anyone’s control …

And yet, she thought, standing here in the arroyo dust, she had the instinctive sense that Rosenberg was right. We’ve blown it. We could have done a hell of a lot more. We could have sent robot probes everywhere, multiplied our understanding a hundredfold.

Lights in the sky. That phrase snagged at her. She thought of the forty-year-old Moon photographs. At the LAX bookstalls she’d found rows of astrology books, on the science shelves. Was that the future she wanted to bequeath her grandchildren?

The sense of claustrophobia, of enclosure, she’d felt since returning to Earth increased.

‘Rosenberg, what is it you want?’

He put on his glasses and looked at her. ‘I want you people to start paying back.’

‘I’m listening.’

He guided her back towards the main campus. ‘If you had a free choice, which planet would you choose to go to? The Moon is dead, Venus is an inferno, and Mars is an ice ball, with a few fossils we might dig out of the deep rocks if we sent a team of geologists up there for a century.’

‘Then where?’

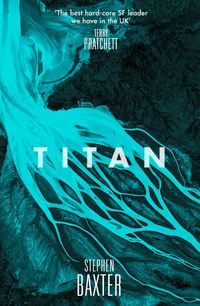

‘Titan,’ he said. ‘Titan …’

He led her to his cubicle in the science back room. It was piled deep with papers, journals, printout; the walls were coated with softscreens.

He sat down. He cleared a softscreen and dug out a Cassini image; it showed the shadowed limb of a smooth, orange-brown globe, billiard-ball featureless. ‘The Cassini-Huygens results have already taught us a hell of a lot about Titan,’ Rosenberg said. ‘It’s a moon of Saturn. But it’s as big as Mercury; hell, it’s a world in its own right. If it wasn’t in orbit around Saturn, if it had its own solar orbit, maybe we would have justified a mission to Titan for its own sake by now …’

Rosenberg brought up a low-altitude image, taken by the Huygens probe a few hundred yards above the surface. The quality was good, though the illumination was low. It was a landscape, she realized suddenly, and Rosenberg expanded on what she saw.

… A reddish colour dominated everything, although swathes of darker, older material streaked the landscape. Towards the horizon, beyond the slushy plain below, there were rolling hills with peaks stained dark red and yellow, with slashes of ochre on their flanks. But they were mountains of ice, not rock. An ethane lake had eroded the base of the hills, and there were visible scars in the hills’ profiles.

Clouds, red and orange, swirled above the hills and flooded the craters …

It was extraordinarily beautiful. Benacerraf felt she was being drawn into the screen, and she wanted to step through and float down through the thick air, her boots crunching into that slushy surface.

Rosenberg said, ‘Titan is the only moon in the Solar System with air, an atmosphere double the mass of Earth’s, mostly nitrogen, with some methane and hydrogen. The sunlight breaks down the methane into tholins – a mixture of hydrocarbons, nitriles and other polymers. That’s the orange-brown smog you can see here. Titan is an ice moon, pocked with craters, which are flooded with ethane. Crater lakes, Paula. The tholins rain out on the surface all the time; Huygens landed in a tholin slush, and we figure there is probably a layer, in some places a hundred yards thick, laid down over the dry land. Titan is an organic chemistry paradise …’

Benacerraf felt faintly bored. ‘I know about the science, Rosenberg.’

‘Paula, I want you to start thinking of Titan in a different way: not as a site of some vague scientific interest, but a resource.’

‘Resource?’

He began to snap out his words, precise, rehearsed. ‘Think about what we have here. Titan is an organic-synthesis machine, way off in the outer Solar System, which we can tune to serve Earthly life. It could become a factory, churning out fibres, food, any organic-chemistry product you like. Such as CHON food.’

‘Huh?’

‘Food manufactured from carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen. Paula, we know how to do this. Generally the comets have been suggested as an off-Earth resource for such raw materials. Titan’s a hell of a lot closer than most comets, and has vastly more mass besides.’ She could not help but see how his mind was working, so clear were his speculations, so transparent his body language.

‘So a colony could survive there,’ she said.

‘More than that. You could export foodstuffs to other colonies, to the inner planets, to Earth itself.’

She nodded. ‘Maybe. There must be cheaper ways to boost the food supply, though … What about a shorter term payoff?’

‘Oh, that’s easy. Helium – 3, from Saturn.’

‘Huh?’

He said patiently, ‘We mine helium – 3 from Saturn’s outer atmosphere, by scooping it off, and export it to Earth, to power fusion reactors. Helium – 3 is a better fuel than deuterium. And you know the Earth-Moon system is almost barren of it.’

She nodded slowly.

He said, ‘And further out in time, on a bigger scale, you could start exporting Titan’s volatiles, to inner planets lacking them.’

‘What volatiles?’

‘Nitrogen,’ he said. ‘An Earth-like biosphere needs nitrogen. Mars has none; Titan has plenty.’ He looked at her closely. ‘Paula, are you following me? Titan nitrogen could be used to terraform Mars.’ He started talking more rapidly. ‘That’s why Titan is vital. We may have only one shot at this, with the technology we have available now. If we could establish some kind of beachhead on Titan, we could use it as a base, long-term, for the colonization of the rest of the System. If we don’t – hell, it might be centuries before we could assemble the resources for another shot. If ever. I’ve thought this through. I have an integrated plan, on how a colony on Titan could be used as a springboard to open up the outer System, over short, medium and long scales … I’ll give you a copy.’

‘Yeah.’ She was starting to feel bewildered. My God, she thought. We can’t even fly our handful of thirty-year-old spaceplanes. We’ve sent one cut-price bucket of bolts down into Titan’s atmosphere. And here is this guy, this hairy JPL wacko, talking about interplanetary commerce, terraforming the bodies of the Solar System.

Future and past were seriously mixed up here, at JPL.

‘Rosenberg, don’t you think we ought to take this one step at a time? If we’re going to fly to other worlds, wouldn’t it be smarter to go somewhere closer to home? The Moon, even Mars?’

‘The old Tsiolkovsky plan,’ he said dismissively. ‘The von Braun scheme. Expand in an orderly way, one step at a time. But hasn’t the history of the last half-century taught us that it just won’t be like that? Paula, the Solar System is a big, empty, hostile place. You can’t envisage an orderly, progressive expansion out there; it will be more like the colonization of Polynesia – fragile ships, limping across the ocean to remote islands. And when you find somewhere friendly, you stop, colonize, and use it as a base to move on. Titan is about the friendliest island we can see; it’s resource-rich, with a shallow gravity well, and it’s a hell of a long way out from the sun. And that’s not all.’

‘What else?’

‘Paula, we think we’ve found life down there.’

‘I know. I read the World Weekly News.’

He looked offended. ‘It wasn’t World Weekly News. And it was your daughter’s report … Anyhow, this changes everything. Don’t you see? Titan is the future: not just for us, the space program, but for life itself in the Solar System.’

She looked, sideways, at his thin face, the orange light of Titan reflecting from his glasses. He didn’t look as if anybody had held him, close, maybe since his early teenage years. And here he was, trying to reach out across a billion miles, to putative beings in some murky puddle on another world.

She’d seen people like this before, on the fringes of the space program. Mostly lonely men. Rosenberg was dreaming of an impossible future. She wondered what it was inside of him he was trying to heal by doing this.

She felt sorry for him.

‘Let me get this straight,’ she said. ‘You want me to back a proposal to send another mission to Titan. Is that right? More probes – maybe some kind of sample return?’

He was shaking his head. She sensed that this situation was about to get worse.

‘No. You haven’t been listening. Not another probe. People,’ he said. ‘We have to send a crewed mission to Titan. We have to send people there.’ He turned in his seat and faced her, deadly serious.

‘Rosenberg, if I’d known you were going to propose something like this –’

‘I know.’ He grinned, and suddenly his looks were boyish. ‘You wouldn’t have flown out. That’s why I didn’t tell you. But I’m not crazy, and I don’t want to waste your time. Just listen.’

‘We don’t have the technology,’ she said. ‘We probably never will.’

‘But we do have the technology. What the hell else are you going to do with your grounded Shuttle fleet?’

‘You want to use Shuttle hardware to reach Titan? Rosenberg, it’s crazy even to think of going to Saturn with chemical rockets. It would take years –’

‘Actually, getting there is easy. So is surviving on the surface. The hard part is coming home …’

At a console, Rosenberg started showing her the preliminary delta-vee and propellant mass calculations he’d made; he was talking too quickly, and she tried to pay attention, following his argument.

She listened.

It was, of course, crazy.

But …

She found herself grinning. Sending people to Titan, huh?

Well, working on a proposal like this, if it could be made to hang together at all, would be a hell of a lot more fun than trawling around the crash inquiries and consultancy circuit forever. It would put bugs up a lot of asses. Including, she thought wickedly, Jackie’s.

In a satisfying way, in fact, her own involvement in this craziness was all Jackie’s fault.

And, what if it all resulted in something tangible? A Titan adventure would be a peg for a lot of young imaginations, in a future which was looking enclosing and bleak. JPL might be finished. So might the Shuttle program, all of America’s first space efforts. But maybe, out of their ashes, some kind of marker to a better future could be drawn.

Or maybe she just wanted to get back at Jackie.

She had a couple of hours before the flight back to Houston. She could afford to indulge Rosenberg a little more.

It would be a thought experiment. It might make a neat little paper for the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. Or maybe one of the sci-fi magazines.

She sat down and started to go through Rosenberg’s back-of-the-envelope numbers more carefully, trying to find the mistake that had to be in there, the hole that would make the whole thing fall apart, the reason why it was impossible to send people to Titan.

Nicola Mott did not want to go home.

She and Siobhan Libet, her sole crewmate on Station, had spent the last day packing the Soyuz reentry module as best they could with results from their work – biological and medical samples, data cassettes and diskettes, film cartridges, notebooks and softscreens. Then Libet dimmed the floods in the Service Module, the Station’s main component, and pulled out her sleeping bag.

But Mott didn’t want to sleep. She wanted to spin out these last few hours as much as she could.

So, alone, she made her way through the open hatch and down to the end of the FGB module, the Russian-built energy block docked on the end of the Service Module.

She stared out the window at the shining, wrinkled surface of the Pacific.

The shadows of the light, high clouds on the water grew longer, and the Station passed abruptly into night. She huddled by the window, curling up into a foetal ball. She could see the lights of a ship, crawling across the skin of the darkened ocean.

She – Nicola Mott, English-born astronaut – might be the last Westerner ever to see such sights, she thought.

She was too young to remember Apollo, barely old enough to remember Skylab and ASTP. She’d been eleven, in the middle of an English spring, when Columbia made her maiden flight, and it had been a hell of a thrill. But after a while she started to wonder why these beautiful spaceships kept on flying up to orbit and coming back down without ever going anywhere.

And when she’d come to understand that, she started to realize that she’d been born at the wrong time: born too late to witness, still less participate in, Apollo; born too early, probably, to witness whatever came next.

Still, she’d decided to make her own way. She’d moved to America and worked through a short career at McDonnell Douglas, where she’d worked on the design and construction of a component of Station called the Integrated Truss Segment So, a piece that now looked as if it would never be shipped out of the McDonnell plant at Huntingdon Beach. She’d enjoyed her time at Huntingdon, looking back; the Balsa Avenue assembly area had the air of an ordinary industrial plant, no fancy NASA-style airlocks or clean rooms …