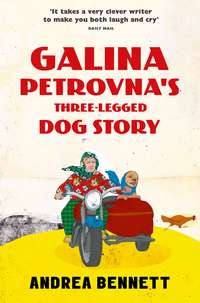

Galina Petrovna’s Three-Legged Dog Story

So the army was not for him. He needed something more direct, a service he could provide locally, with immediate results, and which kept the streets clean of foreign bodies and pestilence. He became a defender of freedom from animal tyranny, a fighter against the disease and nuisance caused by flea-bitten scrag-end dogs: Mitya was a warrior against unauthorized canine infestations. Mitya could not abide a dog. Any dog he saw made Mitya feel sick, the bitter bile rising in his throat, catching at his tonsils, making him cough. But a stray dog: a stray dog made him really mad. A stray dog was an enemy of the state, an enemy of civilization: a personal enemy of Mitya. He contained his loathing through his job, and put his hatred to good use. Any stray in Azov had better be on the lookout: Mitya showed no mercy.

And as the great Soviet Union had finally fallen to pieces and was replaced by a patchwork of republics and autonomous regions, each one jostling the other, he found his own job became semi-autonomous, and he had more freedom to work as he saw fit. While he would never condone the black market, pernicious as it was, it offered up opportunities for armament and persuasion that had previously been out of the question for dog wardens. So, armed with his dog pole, throw net and Taser (not strictly standard issue, but an addition he felt was fully justified), he spent six evenings out of seven patrolling his jurisdiction in the Canine Control Van, or CCV. Mitya was the best Exterminator this side of Kharkov. And the town of Azov relied on him to keep canine vermin at bay, even if they didn’t know it.

This evening, warm and sweet-smelling as only an industrial town on a river in August can be, Mitya was targeting the west side of town, the old quarter, which took in a lot of important staging posts and was always a good hunting ground. His van oiled slowly around the areas beloved of stray dogs: the collage of kiosks selling books, gum, porn, dried fish, vodka and music boxes; the back of the market, where huge bins of rotting mush drew crowds of dogs like flies, with flies as big as bears buzzing around their squirming sores; and the waste-ground outside the shabby church, strewn with begging crones and bones flung down by do-gooders for the dogs that prowled around the old women, and sometimes took a crafty bite out of them when God wasn’t looking.

Mitya started the evening at the kiosks and worked his way around in a clockwise direction. He was swift with his pole: a talented snatcher. He never took on a whole pack. He would observe a group of dogs from a distance and then pick off the weaker specimens one by one as they got distracted and separated. The only way to deal with a whole pack would be by using a stun-grenade or poisonous gas, neither of which was currently approved by the state for dog-warden use, to Mitya’s chagrin. The evening was warm, and Mitya’s skin became wet and sour beneath his close-fitting trousers and regulation shirt. He pulled the van over and took a wet-wipe from his black plastic-leather bum-bag. It was important to try to remain clean and fresh. Mitya had no idea how doggy he smelt. No-one except Andrei the Svoloch ever told him, probably because Andrei the Svoloch was the only person he regularly came in to contact with.

With four matted mongrels already caged and whining in the back, Mitya spotted a lone dog, thin and lank, sitting in a square just off Engels Street on the corner with Karl Marx Avenue. Lone dogs were bad news: even their own canine kind could not stand them. A group of children played nearby. Mitya’s stomach quivered: the dirty dog was salivating, panting like an animal, preparing to savage one of the innocents, there and then. It was Mitya’s duty to spare the child and bring the dog to justice.

‘Master and servant,’ whispered Mitya as he dropped the used wet-wipe into a plastic bag he kept in the van specifically for this purpose, and sprang quietly on to the pavement. He took a few steps into the square and concealed himself behind a set of bins, resting his mini-binoculars on the rim, the better to observe his quarry. He watched, while the dog licked its forepaw, and he blinked, confused: the animal appeared to be a tri-ped.

‘Excuse me?’ a female voice behind him made him jump and drop his mini-binoculars into the open bin with a soft clunk.

‘Christ! Look what you’ve done!’ Mitya thrust his arm into the bin after the binoculars. His fingers came into contact with slime, grit, and soft-boiled cabbage and he winced. He pulled out his hand and turned on the owner of the voice.

‘Oh! It’s you!’ He put his dirty hand behind his back and tried to wipe off his fingers on the edge of the metal bin. It was the angel from the smallest room, Katya. His gaze bounced off the golden hair crowning her head and rested for a moment on her toes, which peeped out from a pair of slightly dog-eared wedge sandals. He found himself imagining his tongue curling around them, and bit on his free knuckle.

‘Oh, I’m sorry! I didn’t realize you were … what were you doing, actually?’

‘I’m working, female citizen.’ Mitya aimed for clipped tones, and tried not to look at the curve of her jeans.

‘Oh, you can call me Katya, you know. You asked so nicely, after all.’

Mitya felt the skin on his face and neck flush hot red, and almost stuttered his response, ‘Yes, but I’m working, and you made me drop my binoculars.’

‘Oh shucks, I am sorry.’ The girl looked genuinely contrite, her brown eyes large and serious.

‘It’s OK. They’re only the regulation ones. Not the special night-vision ones.’

‘Ooh, night-vision binoculars. Wow! Are you spying on those grannies over there?’

‘No, I am not.’

‘What have they done? Are you in the Spetznaz?’

‘No, of course I’m not in the Spetznaz—’

‘But I suppose you wouldn’t be able to tell me if you were!’ She smiled at him and winked in her lopsided way.

‘I’m not in the Spetznaz, Katya. Look, I’m busy right now. What do you want?’

‘Oh, it’s nothing really. To be honest, I just wanted to talk to you.’

‘Why?’

‘Well, I’m new in town, and I don’t really know anyone, except my cousin, and I like to chat. You know, just chat. And I know you – sort of. And I was just curious about what you were doing sneaking around like that—’

‘I wasn’t sneaking around.’

‘And you remind me of someone.’

‘Who?’

‘I’m not sure. But it’ll come to me.’ Katya smiled self-consciously and scraped her sandal across the corner of the flower bed, watching intently as the dry earth broke like brown sugar over her toes. She looked up and caught Mitya’s stare.

‘Look, I just wanted to know if you could tell me how to get to the cinema?’

‘The cinema?’ Mitya asked flatly, his face blank.

‘Yes, the cinema. I’ve never been and I’m having a bit of trouble finding it. I’ve been round this block at least three times and no sign. But the tourist map says it should be here. Look – see?’ She leant towards Mitya and pointed to a blob on the badly reproduced map that was supposed to represent the location of the cinema. He observed her golden hair and the way the streetlight picked up slight reddish tones in it around her ears and the nape of her neck.

‘Ooh, what’s that smell?’ she squealed, looking up suddenly, her golden head nearly colliding with Mitya’s nose.

‘Sewers!’ Mitya bit out, jumping back to a safer distance. ‘It’s always the sewers, and the bins. Look, I’ve never been to the cinema, but I can tell you that it is that way.’ Mitya indicated the boulevard to their left with a slightly shaking finger. ‘Your map is clearly out of date. Or maybe you’ve got it upside down – I hear women often do that. Now, I have important work to do, so, please be on your way.’

Katya looked him up and down slowly, her eyes seeming to reach into every nook and crevice of his body, through his clothes. Mitya shuddered slightly and again felt his skin flush.

‘OK, thank you. But you should go to the cinema some time. They have some good films these days. You could learn a lot! Oh, and,’ she stepped towards him slightly, leaning in conspiratorially, ‘your flies are undone, soldier!’ With a tinkling laugh and a wink she turned and ambled off up the boulevard, her hands swinging slightly, everything about her looking light and fresh and clean and happy.

Mitya yanked up his flies with his sticky hand and for a few seconds watched her progress up the street, wishing he had his binoculars: the binoculars that were languishing in the bottom of the rancid bin. He turned to examine the square: the dangerous tri-ped was still sitting there and the children were still in danger. He turned for one final glance at Katya’s receding backside, and then stared at the patch of earth disturbed by her tiny, perfect foot a minute ago. There was nothing else for it: he was going to have to retrieve his equipment.

‘Hey, you, Citizen Child!’ he called out to a small boy playing under a bench on the edge of the square. ‘I’ve got a task for you. I’ll give you five roubles if you’ll get my binoculars out of this bin.’ He pointed to the bin.

‘Get them yourself, stinky!’ replied the small boy, before running off to find his babushka.

Mitya sighed, and cautiously set about climbing into the bin.

* * *

Ten minutes later, like a cabbage-encrusted stay-pressed sheriff from the old Wild West, Mitya loped into the courtyard towards the dog, his pole over one shoulder and a few streaks of pork fat in the opposite hand. He had egg stains on his trousers and something unmentionable sticking to the sole of his left shoe, but he didn’t care: the binoculars were again his, and now he was fully primed to bag this three-legged son-of-a-bitch.

‘Here doggie doggie doggie!’ he called in a strange, soft, high-pitched voice.

The children on the swings looked up at Mitya’s approach. Old ladies buried their stories mid-grumble and sucked in their gums, while the little ones at their feet moved back, their snot-sticky fingers forgotten half-way between nose and mouth. Masha, the tallest and the leader of the gang, stopped stirring her dirt pie and dropped the stirring stick back on to the dusty ground, hands hanging by her sides, watching. The Exterminator’s steps were unhurried, taking him gently over the ground that separated him and the dog in his sights.

‘That dog isn’t stray,’ said Masha, bravely.

‘Hush, Citizen Child. This dog has no collar.’ Mitya stepped forward, and extended his hand towards the canine.

‘Yes, but she’s not a stray,’ she persisted, doubt and fear making her voice wobble slightly, and she frowned.

‘Yes, she’s right – this dog is no stray!’ Baba Krychkova broke in.

‘It has no collar. It is illegal. And it is dangerous.’ Mitya approached ever nearer, moving carefully, his feet barely making a sound.

‘But she belongs to Galina Petrovna!’

‘No, little girl: it belongs to me.’

Boroda, who had been dozing with the scent of wild olive all around her, woke with a start and peered up at the stranger moving slowly towards her. She felt an odd sort of twinge: she sensed pork fat, mixed with a riot of other scents that made her hair stand on end. But the pork fat was the strongest, in fact somewhat overpowering. The hand that reached out to her was relatively clean and calm and sure, the finger-nails short. She hesitated, and heard a strange chorus of barking from somewhere nearby but closed off. She couldn’t make it out: her hearing wasn’t as good as it had been as a pup. The hair on her back was still raised, her spine tingling, but she felt safe here in the courtyard, with the old ladies and the children. She inspected the stranger more closely as best she could in the dusk. She sensed no vodka or big sticks, and he certainly didn’t appear drunk. And people with pork fat were generally good, weren’t they?

4

A Chase

The shrieking at the House of Culture peaked to a crescendo that threatened to crack the windows and then died down slowly, somewhat like a fire ripping through several shops and an old people’s home, consuming everything in its path but now reducing to glowing embers, every so often expelling a mouthful of acrid yellow sparks and fizzes of burning fat. Vasya had corralled the oldest old woman and her gang to one side of the hall with the promise of tea and cards and the strategic positioning of some folding chairs, while the second oldest old woman and her hangers-on were hemmed in on the opposite side, being plied with biscuits and soothed with spider plants. In the middle, there was a floating ridge of ladies who had no interest in politics, history or rain, and they presided over an uneasy peace. Vasya congratulated himself on having restored some sort of order and felt the chances of successfully bringing off the Lotto draw were now not worse than evens.

As calm was restored within the hall and relative quiet ensued, a row of barking dogs broke out like sniper fire, far off on a distant river bank, giving the breeze a sharp and threatening edge as it drifted over the town. Galia, dishing out biscuits and helpful tuts and sighs to the ladies who hated Communism, hesitated mid-flow on hearing the noise. It was a good thing that Boroda was at home under the table, out of the way of those packs of stray dogs. She recalled the mutts she had seen that day outside the railway station: wild and toothy with matted fur and dripping backsides. She collected herself, and asked if anyone had any further questions about the cabbage root fly.

As she sat down after batting away a vague concern over the use of pesticides – all methods of defence must be considered – a chill ran through her as she remembered that Boroda was not locked inside the flat, but was out in the courtyard. The noise of the dogs was continuing, getting louder and then dipping away again, making no sense, like troublesome conversations in a bad dream. During a lull in the barking, the sleeping man, utterly peaceful until that point and marooned in the middle of the room, suddenly awoke with a cry and slipped from his chair on to the floor with an ominous, muffled crack. A furore of clucking broke out as twelve old ladies around him sprang from their perches to circle him like flapping chickens, or perhaps well-meaning vultures. The old man groaned as he was put in the recovery position by an old lady who had been a grocer, and then turned around and put in a different recovery position by an old lady who had been a nurse. An old lady who had been a construction worker was just about to have a go herself when Galia joined the fray, offering to straighten the old man’s leg if he bit on a metal spoon. His other leg was raised, and lowered, and raised again by the construction worker, as an old lady who had been a teacher tried to get everyone else to sit down and listen to her instructions. No-one listened to Galia’s offer to straighten the leg apart from Vasya, who begged her to be patient for a few moments while the construction worker attempted to find out which bit of the old man, if any, needed straightening. Galia stood by the Chairman’s desk and, with nothing else she could helpfully do at that moment, selected a red boiled sweet from the bowl in front of her and popped it into her mouth. The concentrated sweetness made her gold teeth ache, but still, it was sweet.

‘Turn him over!’ bellowed the construction worker.

‘Nooo!’ groaned the old man, who Galia now recognized as Petya, who used to be around six foot six and had been an engineer: quite high up, and once very athletic. A broad, tall, dependable man, who now lay on the floor being re-arranged by a gaggle of hens.

‘Citizens, perhaps we should wait for the skoraya? Has anyone called them? I say, has anyone called an ambulance?’ Galia shouted over the melee, but there was no discernible response. She made her way out of the room, down the grand marble staircase and over to the reception desk, where a lady in a bobble hat sat knitting a blanket. ‘Please call for an ambulance, Alicia Nikolaevna, there has been an accident.’

‘An accident? Another one? What do you old birds do up there? That’s the third time this summer!’

‘Please just call the ambulance, Alicia Nikolaevna. There is a man in pain, and he needs help.’

‘And it’s always the men, isn’t it? Why is it always the men? What do you do to them up there? Poor old Afanasy Albertovich last month, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes, that was most unfortunate, but please – just get on the phone, Alicia Nikolaevna.’

‘I’ve not seen him since, you know! No-one has!’

Galia gave the door keeper a stern look, for several seconds. ‘Alicia Nikolaevna, the phone—’

‘Yes, yes, I’m doing it! I’ve just got to finish this line.’

Galia thumped her hand on the desk with a gravity that surprised both of them. The other woman slowed her knitting, completed a stitch and put it down with an exasperated sigh.

‘Some old people should know their places!’ Alicia Nikolaevna shrilled as she reached for the phone.

Galia strode back up the grand marble staircase with purposeful steps. Just as she reached the top, the big metal doors at the front of the building clattered open and a stampede of small feet slapped their way across the grand hallway in an awful hurry and made straight for the staircase.

‘Stop, no children allowed in here! Get out!’ cried Alicia Nikolaevna, jumping up from her chair and dropping the knitting and the phone to the floor.

The children slowed and glanced at her briefly, but on spying Galia at the top of the stairs surged forward again en-masse.

‘Baba Galia, Baba Galia! It’s terrible! Come quick! Something terrible has happened!’

Galia’s jaw sagged slightly, and she wished she hadn’t wished for more excitement at the Elderly Club.

‘What, children?’

‘He’s taken Boroda!’

‘Who? What are you talking about?’

‘The dog van! The Exterminator! He’s taken Boroda!’

‘We told him she wasn’t wild, but he took her with the others anyway, and put her in the van.’

‘He said she hadn’t got a collar on, so she must be wild. He said it’s the law!’

‘She left her headdress behind, Baba Galia! I found it in the street! Look!’

‘Shut up you idiot, what does that matter? They’re going to gas her!’

‘No, they’re going to shoot her. That’s what he said.’

‘No, he said they would exterminate her by all means necessary.’

Galia looked at the broken leafy headdress, her mouth open. She felt her knees buckle and dropped the metal spoon she’d been clasping for the last five minutes down the concrete steps, the sound reverberating off the marble like a mad church bell. Her kneecaps cracked on the floor where they hit, the goodly layer of flesh not enough to cushion them, and even Alicia Nikolaevna looked up from her desk with a flash of sharp interest on her face.

‘Baba Galia, are you ill? You must get up and run after the van!’ one of the children cried as they tugged at her shoulder.

Galia could not speak. In the deep black night enveloping the building, they heard the faint imprint of a howl as a rattling engine passed by a couple of streets away.

Vasya Volubchik let the old man’s head drop with a soft thunk when he saw Galia, out on the landing, drop to her knees. This was not good. The old man would have to be left to the women. Vasya hobbled over to the door and stood hovering gently, unsure where to begin.

‘Galia my dear, what’s the matter? Are you ill?’

‘No, Dedya Vasya, Boroda has been taken away by the exterminator van! They are going to gas her! She will be eaten by the wild dogs and then gassed!’ Masha, the tallest and boldest, started to cry.

‘My goodness, is this true?’

The children nodded vigorously, all of them now sniffling and dripping like leaky buckets.

‘Galia, there is no time to waste, why are you on your knees? Get up, get up, woman!’ Vasya gripped Galia’s shoulders and looked into her face. He always thought this moment would be full of joy, to touch her and gaze into her eyes. But alas, it stopped him short and made his heart thump in a most unpleasant way. Because for a moment, his Galia was lost: the dependable, stolid woman had disappeared and been replaced by a frightened child dressed up as a haggard old lady with death in her eyes and her mouth wide open.

‘Galia, listen to me: don’t despair. Even if the Exterminator has got Boroda – and we don’t know that for certain – it’s not without hope. We can go after him! And, and even if that fails, I know where he lives, that Mitya the Exterminator. We can find him! Now is no time to sit on the floor. Look – the old ladies are looking at you; they think you’ve lost your reason!’

And indeed, the coven had, as one, ceased to minister to the old man with the broken hip, and were gathered, goggle eyed, at the doorway, watching Galia minutely, while the old man took up groaning again and pleading for a nip of vodka, or a swift death.

‘But it’s too late, Vasya, she’s gone. She’s in the van already.’

‘We can chase him down! Listen. My bike is just outside. I’ve been tuning it all day. It’s running like a dream and ready for anything. We can do it, Galia!’

And with the help of the children gathered around him, together they levered Galia upright, dusted her down and jostled her down the steps, through the clattering metal doors and out into the darkened street. At the kerb, Vasya’s ancient but gleaming Ural motorbike and sidecar waited, a vision of polished chrome and blood-red paintwork.

‘Get in, woman, get in!’

Galia held the ends of her headscarf close to her chin and eyed the gleaming motorbike and its deep, narrow sidecar. She knew she would never fit. Her brows drew together, and then she spoke.

‘You get in, Vasya.’

She caught Vasya’s eye, and held it. ‘I’ll drive. It’s the only way.’ Vasya looked from bike to woman to sidecar and back to woman, and then at his shoes. She was right.

‘OK, but follow my instructions.’

‘But of course, Vasily Semyonovich.’

‘Listen!’ cried Masha. They froze, Vasya with one foot the size of a tennis racket in the sidecar, Galia with skirt hitched above her knee, the rosy flesh oozing delicately over the top of her pop sock. The wind carried vague hints of sound, a scrap of a rasping engine, a hint of muffled furry fury which could have been the noise of a dozen wild dogs, maybe in a van, maybe in a tin can buried underground. Maybe in hell.

‘That way!’ shrieked Masha, flinging her right arm wildly into the air. ‘Go! Save the dogs!’

Vasya folded his stiff legs in front of him in the sidecar as Galia hitched up her floral skirt still higher and, with an ease that Vasya couldn’t help noticing, straddled the bike. A sandaled foot kick-started the faithful engine and then, headscarf and frizzy hair streaming in the wind, she increased the revs and took off after Mitya the Exterminator’s van.

Across the bridge and the blackened oily river, past the factory, out to the flats on the new side of town they sped. Galia hadn’t ridden a motorbike for at least thirty years, but after the first couple of minutes and a rather hair-raising bend or two, she discovered that it was, indeed, just like riding a bike. Vasya kept a beady eye on both her gear changing and her speed, while also trying to make out the lights of Mitya the Exterminator’s van in front of them, and the exact texture of the pink flesh that was oozing at him oh-so-beautifully from the top of Galia’s pop sock.

Vasya was aware at this moment that he was a truly modern man, in every sense: not only had he allowed the woman to drive, but he could multi-task, even in a dangerous and unusual situation like this. He congratulated himself, briefly, before the discomfort of being thrown violently forward and his nose coming into close contact with his knees concentrated his mind on other matters, such as the blood spots on his trousers.

Every so often they pulled over to ask teenagers snogging on benches or sniffing glue to tell them which way the Exterminator had gone. Everyone knew his van. When they reached the newest new flats, they glimpsed the van’s red lights for the first time, meandering through the suburbs, looking for dogs to make disappear. Their eyes met for a moment, and then they surged onward. Hearing nothing over the roar of the engine and seeing nothing apart from those twin red lights, they gradually reeled them in, getting closer, starting to make out the back of the van through the thickening dark.