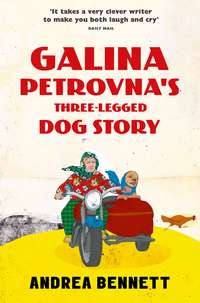

Galina Petrovna’s Three-Legged Dog Story

Mitya cleared his throat, and winced, as if the action caused him pain. He should have warmed up in the car, he thought, but this drunken fool had distracted him. Now he appeared weak, nervous, mucus-ridden. The prolonged incident with his mother had, in truth, unnerved him somewhat and left him feeling slightly unwell. But the fight went on, and the canine had to be brought to justice, no matter how tired and spent he was. He could sense the damp from the basement on the East Side still sticking to his clothes, and his nostrils quivered as he caught a sour whiff of something, which he thought must be the policeman.

‘Orlova, Galina Petrovna?’ Mitya spoke, the pitch a little higher than he would have liked.

Galia nodded slowly, still looking at the greasy policeman, and wondering if she knew his mother.

‘You have in your apartment a dangerous dog, which I am here to remove.’ There was a pause, and Mitya coughed. ‘My colleague here, as you see, is somewhat tired. It has been a long day.’

‘It’s my saint’s day today, Baba!’ chipped in the policeman.

‘However, our actions have all the force of law, and he is armed. Now I call on you to stand aside so that the dangerous canine can be removed.’

‘It’s my saint’s day every day! This modern Russia is sooooo great!’

Galia ceased examining the drunken policeman and turned her gaze to Mitya the Exterminator.

‘Where are your papers, sir?’ she asked softly.

Mitya the Exterminator thrust seven sheets of paper into her face the instant the words left her mouth. All stamped, sealed, laden with official signature, her address, details, birth date, star sign even. She was about to relent and vacate the door space to allow them in, when Vasya joined her on the threshold, looking flushed, breathless, excited even: in a word, a dangerous condition for an elderly man in the middle of the night.

‘Now then young Mitya, we don’t want any trouble here,’ he began. The Exterminator’s eyes became clouded and his cheeks flushed a dull red at the words. ‘I am sure we can sort this out without any unpleasantness. What exactly is the complaint against the dog?’

There was a long pause, filled only with the sound of the policeman shifting from foot to foot and back again, a casual move that required a huge amount of concentration in his present state, and made the sweat drip off his stubby, turned-up nose. Mitya breathed deeply and evenly, his eyes still far off, his hands loose by his sides. Gradually, just as Galia was wondering whether he was still fully conscious, he drew his eyes back from the middle distance and re-focused on Vasya for a few seconds. He reached for his plastic-leather bum-bag and pulled out a notebook. He cleared his throat, peered closely at Vasya for a second time, and then started to read, ‘“That on the aforementioned date said canine did bite the official state dog warden both on the finger and on the ankle and when commanded to desist did recklessly continue to bite the official state dog warden further to said aforementioned place both on the calf and on the wrist. This being an offence under Article 27 of Presidential Decree 695 and in direct contravention of the laws of the Russian Federation, said dangerous dog is required to be exterminated forthwith before it becomes a menace to society.” And that’s the President of the Russian Federation that wants your dog dead, Citizen, not just me.’ Mitya finished with a rush and a prolonged frown.

‘But Boroda would never bite anyone, let alone an official state dog warden!’ cried Galia, offended on the dog’s behalf, and worried by the thought that the President himself could think so badly of her. ‘She is a good dog – a shy dog. She knows what it is to be a stray and has respect for all citizens. She knows an official when she sees one.’

‘A stray, you say?’ enquired Mitya.

Galia hesitated, her eyes wary, not sure what answer she should give.

‘But Galia, isn’t that the dog, exactly the dog, that you took to the river just this evening to drown?’

Galia glared at Vasya for a second as if he had pierced her heart with a knitting needle. Indeed, he thought she might at any minute attempt to strike him, as she raised her hand in horror and leant towards him. He even took a slight step back at the look in her eyes, inadvertently stepping on the drunken policeman’s bunion. This was a grave and fateful error, as he let out a howl that caused an answering howl to echo from deep within the apartment, which made the Exterminator’s left eye twitch. Galia regained her composure in an instant, as if slapped, and coughed loudly to try to drown out the sound of the howl. She nodded slightly at Vasya.

‘Yes, yes, Vasily Semyonovich, you’re right. Gosh was that your stomach – you must be hungry. We have been so busy this evening … The dog … had to go. Yes, she had turned a bit funny, and I am old, and I thought, well, I can’t cope, so … heart-breaking as it was—’

‘We dropped her in the river in a bag full of stones,’ Vasya confirmed quickly, pulling the door almost shut behind him, as he heard Boroda whining in the depths of the wardrobe.

‘The dog is in the river?’ asked Mitya softly.

‘Yes, yes,’ Galia replied, eyes on his second button, hands twisting slightly in front of her. ‘She had to go. I didn’t really want to say … you know, people talk about rights for animals these days, and everything.’

Mitya removed a small red rubber ball from his bum-bag.

‘In the river, you say?’

‘Yes sir, in the river. About a mile down-stream from here. Where it’s deep.’

‘Stand aside, Elderly Citizens.’ He bent towards the door.

‘I say, have you got a permit to do that?’ asked Vasya gruffly.

Mitya squeezed the small red rubber ball sharply and deliberately, three times. It squeaked with a raw venom that zipped up the Elderly Citizens’ backbones and puckered their faces like limes. A small silence was followed by the inevitable clang of doom: a clatter of clever-stupid claws on the wardrobe door. ‘Here doggie, doggie, doggie!’ called Mitya in a strange, childlike voice, squeezing the ball again, and dropping a few morsels of bacon rind on the floor just inside the door.

‘Now then, young man, who gave you permission to strew—’ began Vasya.

‘Stand aside, Volubchik,’ commanded Mitya with some force, placing one finger in the centre of Vasya’s chest.

The squeak and the bacon rind had worked their sensual magic. Their long, chewy fingers of saltiness had reached out to the dog and hooked around her nose, dragging her forward almost against her will, out of the bedroom door and into the hallway, claws skittering softly on the ragged parquet despite herself, edging for the bacon rind and the door, the open door where her mistress stood talking to some familiar, but all the same slightly terrifying, guests. The dog gently scooped up the bacon rind with her tongue and chewed it with sad eyes as they watched. Then, rather apologetically, she wound herself behind Galia’s legs and whined softly.

‘She floats,’ said Mitya, ‘despite the stones: she has risen.’

‘Now please, Mitya, there’s no need to take the dog. I’m sure we can come to some kind of arrangement,’ and again Vasya reached for the greasy wad of notes tucked into his shirt. No man could resist the call of real Russian vodka, and fish dried right there on the riverbank, surely.

‘Put your money away. Officer, this is the second time in four hours that this man has attempted to bribe me, a state official and dog warden. But, Elderly Citizen, this time we have a state enforcer of the law on hand to witness it and I have no distractions to stand between me and bringing you to justice. You cannot get away with such undemocratic and anti-establishment behaviour a second time.’

Mitya waited for the chubby policeman to take action. All three of them, plus the dog, stood expectantly, gazing at Kulakov and waiting for the cop to take his cue. As it gradually became clear to all, including Boroda, that the chubby policeman was far too interested in the fluff inside his whistle and other contents of his breast pocket to take any individual action, Mitya pulled him to one side and hissed in his ear.

‘Officer Kulakov, arrest the old man: he is trying to bribe me! He is trying to bribe you, too! He is corrupting the State!’

‘Arrest him? What for?’

‘Look, I’ll give you two bottles: just arrest him.’

‘For what?’

‘Bribery!’

‘But all the paperwork, Citizen Exterminator, all the kerfuffle: it’s really too much. It’s more than my job’s worth. Really, let’s just go home.’

‘But a crime has been committed, Officer Kulakov.’

‘Ah, a crime, what crime? Oh, OK, OK … what was it?’

‘Bribery!’

‘Ah, yes … well, make it three bottles, and then I might consider it.’

‘Very well, three it is,’ said Mitya, releasing the policeman’s arm and wiping a clammy, warm feeling from his hand on to his trouser leg.

‘You, Citizen Old Man,’ the chubby policeman snapped in a piercing tone at odds with his padded appearance and previous demeanour, like a Pooh Bear channelling Hitler at the Reichstag. ‘You are under arrest. Come with me, don’t struggle.’

The policeman lurched towards Vasya with quick, widely planted steps and deftly twisted the old man’s arm up behind his back with a cruelty that took even Mitya by surprise. Vasya yelped as the two began an unsteady march towards the stairs. Boroda, the quickest to react to this obviously unfair behaviour, launched herself across the hallway and tackled the policeman’s ankle just as he made the top of the stairs. Snarling, growling, snapping and yipping echoed from the stairwell walls as the policeman battled to free his ankle and Vasya struggled to free himself without tipping over the bannisters. Sharp white teeth sank into freckled sweating flesh and brought tears to the eyes of the policeman. Mitya could see that Kulakov was no match for this mutt and reached for his Taser, but couldn’t get a clear shot. He was tempted to shoot anyway, just to see what would happen, but was knocked to the ground face down by Galia who, after several seconds of total immobility, realized that things were looking worse for everyone, but especially her friends, and charged in to call Boroda off.

‘Boroda, quiet!’ Commanded Galia in a voice that shook the walls. The dog released the policeman and retreated towards the stairs. Mitya scrambled to his feet and, pushing the wailing chubby policeman out of the way, grabbed the dog by the scruff. She yelped as he lifted her high into the air and suspended her over the stairwell.

‘Quiet, Boroda,’ commanded Galia again as the dog twisted and turned in Mitya’s grasp, trying to get at least one fang into the sinews of his wrist. Mitya watched the dog’s efforts, and smiled, briefly.

‘Citizen Old Woman, the only thing stopping me from dropping this thing over the bannister is the mess it would make on my boots when I stepped through it on leaving the building. Uncontrolled canines are vermin, and this vermin must be controlled. I am now taking charge of this animal and it will be exterminated. You have the paperwork. It explains your rights.’

He started down the stairs.

‘What rights?’ shouted Galia after him, desperate.

‘To the body: you have none. It will be burnt, along with other vermin,’ with a half-smile, Mitya marched further down the steps with Boroda still held at arm’s length by the scruff of her neck, still twisting, still whining.

‘Please!’ wailed Galia.

‘Kulakov! Wake up and take that man to the station! Three bottles, remember?’ called Mitya from the next floor down. Vasya was, by this point, seeing to the injured Officer Kulakov, helping him back to his feet and offering him iodine and cotton wool, which he waved away with an oath.

‘My apologies, Citizen Old Man, but it seems you must accompany me to the station. Bring any medication you may need. This may take some time. I really must arrest you, you see.’ Leaning on each other, they began slowly down the concrete steps, Vasya supporting the wobbling policeman to the best of his ability. They passed Galia as she watched Mitya disappearing into the darkness with her dog.

‘Go inside, Galia, and lock the door. I’ll be OK. Don’t worry.’ Vasya shot Galia a worried look, but failed to catch her eye: she was still watching after Boroda, receding into the darkness, whimpering and afraid.

‘Don’t worry, Galina Petrovna, I’ll be OK,’ he shouted louder, ‘and I’ll free your dog! Don’t give up hope! We live in a democracy. Dogs must be free, just as people must be free!’

The words pierced Galia’s thick bubble of shock. ‘Vasya, be brave,’ she said. ‘We’ll get you out. You’ll see. We’ll get you out tomorrow. You and Boroda. I’ll make sure of that. They have no grounds for taking you!’

‘Tomorrow? We won’t even have started on the paperwork by tomorrow, Elderly Citizens,’ mumbled Officer Kulakov as he folded Vasya into the back of his Zhiguli police car and then took his position behind the wheel. ‘OK Citizen Old Man, we’re just going to have a little nap before we set off for the station, so just make yourself comfortable. There’s no point us getting there before six. Nothing ever happens there before six. We may as well sleep things off here a bit, and then go in with a clear head, don’t you think?’

Up in the apartment block, Galia stumbled back in to her flat and clicked the door shut. In the kitchen, with no company save the empty dog box under the table and Vasya’s tea glass, still half full, waiting for him to complete his toast to the bright future, she began to shake. The only sound now was the clock, ticking away the quiet, lonely night, with an occasional soft bong to mark the march towards dawn.

6

The Plan

Galina Petrovna did not sleep well. After struggling to undress, feeling like an old woman, maybe the oldest old woman in the town, or even in the whole of Russia, she eased her way into her favourite, most comforting poplin night dress and lay on her bed, exhausted but wide awake. She was barely able to unwind her lids and shut her eyes, let alone nod off. Her eyeballs stuck to her eyelids; there was no comfort in her head, and no restfulness in her body. She lay taut on top of the covers and stared at the top of the wardrobe door. After several minutes listening to herself breathe, she sighed and gingerly pushed herself vertical. This would not do.

With a solid determination to be sensible and not give in to needless and unhelpful despair, she tried all the methods in her repertoire to relax into sleep as the night wore on. She started by sitting at the kitchen table, wrapped in a blanket, making scratchy lists of jobs to do in order to empty her brain; then she walked the floor with deliberate, certain steps, no doubt annoying the light-sleepers downstairs but feeling the need for movement; she cleaned the kitchen cupboards, clanging about at three a.m. and finding four dead cockroaches, two bottles of tomatoes from 1975 and a mouse trap (empty); she forced down weak tea with so much added jam you could stand a spoon up in it; she had a bath with oil of lavender so strong it took her breath away; and eventually, giving in, she took a tablet. Galia wasn’t one for tablets: the only discernible effect of this one was to turn her water green for the whole of the following day. Still she did not sleep.

At five a.m., after several half-hearted attempts at a gardening crossword, she went back to bed feeling cold and despondent despite the promising glow of the rising sun. She turned from one side to the other and then back again, replaying all the events of the evening and things that could have turned out differently, and most of all chiding herself for being a stubborn old idiot and not getting the dog a collar from the outset. If only she hadn’t stood on a principle, none of this would ever have happened. Poor Boroda would not be awaiting execution, and old Vasya would be asleep in his own bed instead of languishing in some prison cell far across town. And slowly, once all the scenarios had been churned over and re-jigged to exhaustion and started getting jumbled up with one another in her tired mind, she absently and unwittingly turned to examining problems further back in time: situations, places and people she had left behind a long time ago. The theatre behind her eyelids was filled with scenes and characters about whom she hardly ever thought when she was busy with her garden, her card games, her vegetables and her Boroda.

She dozed fitfully, and remembered a time when she was young. Back then, when things were different, life was properly difficult and her memories of it were dark. She remembered clattering footsteps in the stairwell, and the dry choking dust coming off the unmade roads in huge silvery plumes all summer. It was a time when work was a twelve-hour day at least, and sparse summer harvests had to be made to last all winter. When they first moved in to the apartment, the electricity, which they were very lucky to have, went off in the evening. That was no great problem, as they had no fridge and no TV, and generally no need for light after eight p.m. In those days, the lazy got nothing, unless they were the bosses, in which case they got theirs and a slice of everybody else’s, and more besides. She remembered her elderly neighbours: they were respected, but had nothing, and hoped for nothing, except maybe a better future for their grandchildren, if they survived. She tried to visualize the faces of some of those friends and neighbours who had gone away years ago and never come back, but the images were smudgy, lacking detail. Too much time had passed. There had been no miracle reunions, no matter what the films in the mobile cinema tried to make you believe. The disappeared did not come back.

The war had left Galia an orphan, but found her a husband, for which she was grateful. The move from active duty to dealing with the burdens of married life came very quickly. Galia found her new domestic chores rather stifling: occasionally, her heart beat fast against her ribs and she felt a little nauseous, a little trapped, a little desperate, sitting on her stool in the stuffy flat, waiting for Pasha to return from the factory.

She had no previous connection to the town of Azov: Pasha was required to work at the factory, which produced things that she was not allowed to know about, so they were posted to the town by the Regional government soon after the war’s end. At first they lived in a wooden shack, along with the old lady who was the original tenant and a number of her livestock. Once the factory had been fully rebuilt, new apartments for workers were slotted together with amazing speed, and Galia knew they were lucky to be among the first to be re-homed. At first, they shared the two rooms plus kitchen and bathroom with another family whose baby girl howled all night and whose grandfather howled all day. After a year or so the others were re-housed, and Galia missed the baby once she had caught up on her sleep.

Azov was a sociable southern town: the people promenaded in the summer evenings, slapping mosquitoes from their legs and always wearing Sunday best if they had it, no matter what day of the week. In the wintertime, when the river froze over and the icy wind snarled in from the north, the locals would wrap up in all the clothes they possessed and go skating over the fishes and the weeds. Married men would seek the silent companionship of ice-fishing as long as the river would take their weight, and day and night, blizzard or sun, they sat over tiny holes drilled through the leaden surface, waiting for a bite or a nip from their own bottles hidden away under piles of bread and pork fat supplied by their loyal wives. Pasha never went ice-fishing though. Galia would have liked it if he had, but her suggestion was always met with a shrug and a sardonic smile. Pasha kept himself to himself.

Galia loved the river with its changing face and wide, sunlit banks, but no more than she enjoyed the old town walls and the crumbling fortress, red brick and fusty, which repelled invasion by no-one these days, but was chock-full of stories and ghosts. As a young woman, Galia had been impressed with Shop No. 1, Shop No. 2, the shoe shop and the newly built Palace of Culture. It seemed to her that her country was indeed building Communism and rebuilding itself into a better, fairer, and brighter place. The factories and the schools that sprang up around the town were right on her doorstep. It was all new and as fresh as dew on green tomatoes, for a while. Galia felt part of this beginning and wanted to take a role in the real work of the collective, her union, the Soviet Union.

But at home, life was never simple, and it never reflected the Soviet model that, for a while at least, Galia hoped it would. When Pasha chose to sit and drink, she would stay in the kitchen and work methodically on enough vareniki for a month, gifting them out to the toothless old men and women from down the hall, when they were well enough to be roused by her knock at the door. When Pasha fell asleep at the vegetable patch during the harvest, she carried on, working all day without a break, and ensuring that he was shaded as far as possible so that his translucent pale skin did not peel. When he’d slap her backside with a pink hand and lead her into the shed for a glass of home brew and a cuddle, she tried not to think of her aching back but instead focused on the love that she hoped his attention signified. His stubble and the stale tang of sleep on his tongue sometimes brought a tear to her eye, but the intimate rub of bare wood on her buttocks as he moved inside her sent little shock-waves of desire through her belly and down her legs, and made her toes and fingers curl into tight knots of pleasure.

But in truth, Galia had realized fairly early on that she didn’t really like Pasha at all. Once she had accepted this to herself, as a woman of principle, she became determined to make a good wife for him, as far as was possible: he was to be clean, his socks darned, meals provided, and other needs met. But despite her good intentions, it was not many years before her interest in him shrivelled like a late rose caught in a sly first frost. Once the home brew had dried up and the shed became a place where only the seedlings received any attention, she squared her shoulders and got on with other things. In time, this became her mantra: get on with things, and don’t complain, and all will be well.

Pasha had started being away when he should be home almost before the wedding feast (boiled meat, potatoes, kvas and apples) had been fully digested and forgotten by all those concerned. Not that there were many guests to be had at their nuptials, most of their relatives and friends being missing, dead, in prison or building Communism elsewhere in the huge Union. Pasha’s absence hurt Galia at first, but in a dull sort of way. She had expected a man who would be there, making demands on her, eating her food, sleeping with her, giving her ultimatums, making a mess and demanding her attention when she was busy. But mostly she saw the back of his head: as he sat at his desk in the main room, studying papers from the factory, fingers and stubble streaked with ink; or as he stood on the balcony staring out into the evening, smoke from his cigarette rising straight and listless into the still summer sky; or as he slept on the sofa, sucking air noisily out of the room and hiding it in the cavity of his chest like a miser hoarding candle ends. And then there was the quiet mockery of the click of the closing door, sometimes mid-sentence, sometimes just before a meal. Galia ate many meals for two alone. When she was lying on the bed waiting for him, wondering if there was something wrong with her, with her frizzy blonde hair and her pale skin, she’d finish off his pie, lick the fork, and tell herself it didn’t matter. Good food, honesty, timeliness, good neighbourliness: these were worthy enough causes.

At first she would listen to the familiar bossy tones of the radio while she waited. Sometimes housework kept her occupied, or some mending. She’d watch the children playing in the courtyard between the brand new blocks of flats, occasionally shouting down half-hearted remonstrations. And she would cook, even on the evenings when he did not come home at all, she would cook. Her favourite was vareniki like her own mother had made. Often she bottled fruit or vegetables, and when she’d run out of her own produce she’d take in endless cherries, plums, cucumbers and tomatoes from her neighbours to do the same for them. Her life revolved around ceaseless movements and small busy tasks for the hands, her methodical steps around the kitchen comforting and repetitive like notes on the balalaika when she was learning to dance before the war, her mother looking on sternly. How had she forgotten that for so long?