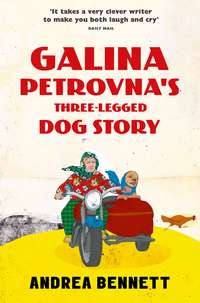

Galina Petrovna’s Three-Legged Dog Story

‘Look out!’ Vasya shrieked and Galia squeezed the brakes as hard as she could, as a shoddy-looking ambulance careering in the opposite direction zig-zagged towards them across the middle of the road, siren blaring. The bike skidded crazily and came to a stop just short of the ambulance, side on. Galia panted as the grim faces of the paramedics, sucking on roll-ups on the front seat, grazed past her nose. They were near enough to touch: no, near enough to kiss, and she could smell the interior of the vehicle. Formaldehyde and aspic. ‘Kiss of death,’ muttered Galia with a shudder as she re-started the engine, nodded to Vasya whose face was now the colour and texture of lumpy sour milk, and roared away.

There was no sign of the van. Galia revved the engine and sped along the nameless, characterless streets, past huge blocks of flats with dark windows like empty eye sockets. She had no idea where they were. A cold sweat replaced the hot sweat and she felt the blood drain from her face: there was no sign of them. The long, straight road was thoroughly empty. Seconds ticked by and she felt tears begin to sting the backs of her eyelids. She’d lost them.

She was about to pull over when Vasya grabbed her arm with shaking fingers and pointed to a turning to the right. Galia tutted, and muttered to herself, but followed his instruction.

‘You old idiot, why would they have gone in there? That’s just …’ She trailed off, and pulled the bike up behind a stack of street bins. The van had pulled in to a courtyard between tower blocks that seemed to have become derelict without ever having been finished. She could see vague movements in the mottled darkness.

‘Vasya, how did you know they had come in here, do you have special powers?’ Galia hissed. She wasn’t any more superstitious than most Russian women, but the old man’s insight had intrigued her.

‘Ha, you women, you’re all the same. If a man knows something you don’t, he must be psychic.’

Galia snorted quietly and attempted to dismount the bike with something like dignity, but found it a lot harder than jumping on had been. Vasya disengaged his legs from under his chin and felt the blood returning painfully to his feet. He couldn’t attempt to get out just yet; he knew he’d fall flat on his nose if he did.

Galia began to creep around the bins and into the courtyard to observe the van from a safe distance.

‘Galia, wait for me! Don’t attempt anything on your own!’ Vasya swung his feet to the ground and levered himself into a vertical position, but wasn’t able to walk.

‘Keep your voice down, you old fool!’ chided Galia, still unhappy at being laughed at.

‘I know his mother.’

‘What do you mean, you know his mother?’

‘I know his mother. The Exterminator’s mother. And when he started coming out this way, I guessed.’

‘What did you guess?’ Galia was becoming exasperated.

‘I guessed what Mitya the Exterminator wanted. After a busy night killing dogs, what would any good exterminator want? He’d want to go to his mother’s apartment for some washing and some kasha. It’s what any man would want, surely?’

Galia was just about to respond with some choice words when the rear doors of the van were flung open and a cacophony of howling smashed the night air to flea-bitten pieces. Vasya reached the spot where Galia stood, grimacing at the noise filling the courtyard.

‘What are we going to do now, Galia?’ asked Vasya with a hopeful half-smile.

‘We’re going to get my dog back,’ Galia retorted, and marched, as well as her still-bent and swollen knees would allow her, across the broken ground towards the back of the van. Vasya sighed, words of reply flapping uselessly on his tongue like carp on a dry river bed, and hobbled after her.

‘You have stolen my dog!’

‘Wha—?’ Mitya the Exterminator had been singing under his breath ‘yorr awn, personal dzhezuz’ while removing dog excrement from his boot and his ear with a special knife he kept for that purpose. The dogs were still in cages in the back of the van and he had been mulling over how to ensure that the perpetrator of said excrement never forgot his vengeance in what was to be left of its short life. The sudden appearance beside him of a solid-looking old woman with bent knees and laddered pop socks, shouting throatily and shaking her fists, was both unwelcome and unsettling.

‘You have stolen my dog!’

Mitya sensed that she was angry, and possibly crazy: why else would she be worried about a dog?

‘Who are you, mad woman?’ he asked, his face twisting under eyes that popped with either fear or hatred, Galia was unsure which.

‘You have stolen my dog!’ Galia tried again, finally straightening her legs, although somewhat tentatively. The noise of the dogs in the back of the van filled her head with the sounds of nightmares. Among the howling, barking and growling, she could make out the sound of Boroda, crying softly.

‘Citizen, let me explain,’ said Mitya the Exterminator softly, ‘all the dogs I take have no owner. It follows, therefore, that your dog is not with me.’ Mitya put his excrement knife back in his bum-bag and turned his back on the old woman with funny knees. He hoped she would now disappear as quickly as she had appeared. She gave him the creeps. And he had unfinished business to attend to.

‘You have stolen my dog! She’s grey and has three legs and a small, pointy beard, and she is in the back of your van! I can hear her. Boroda! Boroda! I’m here, darling! Don’t worry; we’ll get you out, lapochka!’

Mitya smiled slightly to himself. The three-legged dog had been a very easy catch, once he’d got out of the bin.

‘Citizen Old Woman, I only take stray dogs, diseased dogs. Dogs that should not be. I never take a dog with a collar. And your dog must have a collar, if it is genuinely your dog. So it cannot be in my van.’

‘No. You don’t understand—’

‘Has your dog got a collar, Elderly Citizen?’

‘No.’

There was a pause in the barking and growling, a silence filled only by the sound of Vasya panting as he made his way across the courtyard. He finally reached them and leant against the side of the van to catch his breath. Mitya the Exterminator turned to Galia and smirked.

‘No collar? Then Citizen Old Woman, you have no dog. You need to familiarise yourself with the legislation, perhaps. End of discussion.’ Mitya turned away to deal with the dogs.

‘No, she is my dog. She lives with me. Boroda! Boroda!’

‘No, Citizen, it is a stray. As set out in Presidential Decree No. 32 of 1994, Section 14, paragraph 3.2 – go home and read it.’

‘So you admit you’ve got my dog? You scoundrel!’

‘Now, now, Galia, my dear, I am sure Mitya, I mean the Exterminator, is a reasonable man. Maybe we could recompense you for the return of the lady’s dog? We’d be happy to make a donation to any charity you’d care to name, or to cover any personal costs.’ Vasya squeezed a wad of worn bank notes from his pocket and fanned them out for Mitya the Exterminator to see. Enough for some vodka and the dried fish to go with it, Vasya thought.

Mitya stared at the money for two seconds and then glanced into Vasya’s face, his nostrils flaring as if the stench of dog had finally sliced into his olfactory nerves. ‘No, Citizen … Volubchik, I don’t want your money. I enjoy my job – do you understand? Not everyone is motivated by money, even in these days of “freedom” and “democracy”.’

Vasya began to stutter a response, but the Exterminator cut across him.

‘No, Elderly Citizen! These dogs have no place in freedom and democracy. These dogs are strays, and they are unhygienic. And I will deal with them. It is my service. Now go home.’

‘No, please!’ Galia stepped purposefully between Mitya the Exterminator and the van. Mitya thought about shoving the old citizen roughly away, but the thought of having to touch her made his stomach shrivel. He decided that the non-standard issue Taser might be the best weapon for this particular job. Vasya gasped as he saw the Exterminator’s hand reach for his holster, and made a dash, on legs still coming to life, to protect Galia.

Galia saw Vasya launch himself at her at the same moment as Mitya the Exterminator fumbled with a holster. She felt afraid, but didn’t know why. Surely he wasn’t going to shoot her?

A second later a screech as if from Baba Yaga herself ripped through the night. All three protagonists froze, with fear squeezing each and every heart. Only Mitya seemed to know the likely source of the chilling wail, and his head jerked towards the entrance to the flats. In a flash, a tiny old woman with a bristling chin and a brightly coloured headscarf darted out of the stairwell with something gleaming raised above her head. It took Galia a second or two to work out what it was: a sickle.

‘Go to hell you son of a bitch!’ she screeched in a pitch so high it set all the neighbourhood dogs off as she lunged at Mitya the Exterminator with a wicked, slashing motion. Galia and Vasya ducked on instinct, but the old woman hadn’t even seen them. Her terrible eyes tracked the Exterminator alone.

‘No!’ he shouted, backing away, hands outstretched.

‘Murdering bastard, get out of here!’ Again she lunged, and the Exterminator lost his footing slightly, backing away, scrabbling like a chicken about to lose its head.

‘Mother, no! Drop the sickle! It’s me, Mitya! I’ve come for some washing!’

Vasya and Galia stared at each other, dumbfounded for a moment, unable to take in the spectacle of David and Goliath that was unfolding in front of them as the tiny woman chased Mitya the Exterminator around the courtyard, screeching like a banshee with the sickle held high over her head.

A chorus of barking from the back of the van reminded Galia that she’d come here to do more than just gawp at suburban madness. Pulling the van’s battered doors wide, she peered into the murk, her ears ringing. Inside she could make out a patchwork of small cages, each stacked on the other, each housing a miserable dog, each miserable dog just a blur of heaving fur interspersed with white teeth that flashed in the moonlight. Hardly daring to touch the nearest cage, which wobbled about as if on its own accord, she spotted Boroda near the back, small and scared. Galia began to claw out the other cages one by one, placing them on the ground as gently as she could while also withdrawing her hands from the feel of claw and drool as quickly as possible. The stench of the stray dogs caught in her throat and she coughed and gagged as the cages came out.

At last she reached Boroda and heaved out the cage. Glancing over her shoulder to make sure Mitya the Exterminator was still thoroughly occupied with what was apparently his mother; she tugged back the bolt and grabbed the shivering dog.

‘What about these poor wretches, Galia?’ Vasya pointed to the vibrating cages and their contents, strewn about the courtyard floor. ‘What shall we do with these? We can’t just leave them!’

‘Do as you think best, Vasya, I can only care for my dog!’ Galia replied over her shoulder, running for the motorbike with Boroda in her arms. ‘Just do it quickly, for heaven’s sake!’

Vasya looked at the miserable cages and their frenetic contents, and decided quickly. Moving them roughly round so that all the cage doors faced in the same direction, he grabbed the Exterminator’s bag of fat bits from the back of the van, strew them on the ground in a brief trail leading away from him, and then, leaning over the cages from behind, drew back all the bolts and flung the doors as wide as he could. Without waiting to look, he then took to his heels and, with an energy he hadn’t felt since the previous decade, hobbled unevenly across the courtyard to where Galia waited for him on the motorbike.

Galia folded Vasya back in to the sidecar and placed the terrified dog in his lap. She felt like a girl again, a feeling she could almost taste, which rose from the pit of her stomach all the way up: she had outwitted the enemy and might live forever, or just till tomorrow …

As they turned a wide arc to return to town, Vasya glimpsed Mitya the Exterminator falling backwards down the cellar steps into the bowels of the building, the raving old woman following close behind, the moonlight licking the edge of her sickle as it crested above her head. Towards them heaved a pack of stray dogs, howling and yapping and hungry for vengeance. Vasya felt his stomach turn over, and turned his head away. Some things were probably best quickly forgotten.

5

A Visit

‘You say you know his mother?’

Galia threw the question over her shoulder.

Vasya Volubchik was finally seated on a stool at her kitchen table, a place he had often yearned to be, but the circumstances this evening were far from how he had envisaged such a visit. His legs ached like he had been kicked by an apoplectic mule, so much so that Galia had had to half carry, half drag him up the stairs to her apartment. The evening’s upsetting events had effectually driven all thoughts of romance, chivalry and honour from his mind. He felt a bit low, a bit stupid, and really rather old.

‘Yes, we were quite friendly, a long time ago. She was a happy little thing, bright as a button. She was always smiling, singing, dancing. She helped out at my school for some years.’ Vasya’s green eyes became filmy, like still ponds in bloom, and Galia turned away again to frown at her hands as she filled the kettle. A small, semi-stifled tut escaped her, despite herself.

‘And that was his mother we saw tonight?’ Galia gave him a sideways glance, one grey eyebrow raised.

‘Yes.’ Vasily’s gaze skimmed the floor, and a slight movement in his papery, transparent eyelids suggested that a little drop of moisture was escaping from each eye. Galia sighed and set the chipped enamel kettle on the stove. Her match lit the gas with a comforting pop and they sat in silence, save for the soft hiss of the burning blue flame and the occasional bumbling drone of a late-night, sleepy mosquito.

‘Vasily Semyonovich, I have to say, she didn’t seem very happy to me tonight. In fact, she seemed—’

‘Yes, she appears to have changed somewhat since I knew her. I believe grief has a lot to do with it.’ Vasya cut her off, his tone a little clipped. Galia looked up sharply: she wanted to know more.

‘Grief?’

‘Oh, it’s not an interesting story, Galia, really it isn’t. Surely you are already familiar with it?’

Galia shook her head. ‘I don’t know the lady at all. She must keep over at the East Side.’

‘It was just a little small-town heart break, you know. Her husband ran off, a long time ago, and her son is a big disappointment, obviously. That’s the long and the short of it.’ Vasya harrumphed for a moment or two and sniffed, folded his lopsided glasses into his shirt pocket and daintily blotted his nose on the back of his index finger. Then, carefully rolling up his trousers to knee height, he pursed his ancient lips and began tending to his shins with Galia’s proffered iodine and cotton wool. Delicate blobs of green appeared on his dry skin, like moss on wintery silver birches. The pain was making him snappy, Galia thought, and the red blood spots on his trousers, now turning to a rusty brown, were also adding to his bad mood. She toyed with the thought of washing them for him, but the realization that he would be sitting in her kitchen for half the night with those shins on show quickly changed her mind. She felt bad for him, but she knew where to draw the line.

‘Have you heard about Goryoun Tigranovich?’ Vasya looked up from his sorry shins to pose the question.

‘What do you mean?’

‘He’s disappeared, apparently. Something to do with some questionable business with oil wells out east, I heard.’

‘Oh nonsense, Vasily Semyonovich! He’s gone on holiday that is all. You shouldn’t believe everything that every gossipy old bird tells you, you know.’

Vasya returned his attention to his shins, and Galia felt guilty for snapping.

‘Who did her husband run off with?’

‘Whose husband?’

‘Mitya the Exterminator’s mother’s, of course.’

‘Oh, that. Not who, what.’

‘What?’

‘Exactly! Apparently, he took their entire potato harvest, a year’s stock of jam, a pig, a quart of home brew and three sacks of onions. She never got over it. It affected her mind.’

‘Yes, I can imagine,’ Galia said quietly. She passed Vasya a cup of black tea with raspberry jam huddled in the bottom of it. The cup bore the legend ‘Stalingrad – Hero City 1945!’ and was one of Galia’s favourites. She then lowered herself on to her stool near the fridge. When the weather was this close, and all clothes felt like warm wet sheets binding her body, she liked to sit with the fridge door open and her shoulders resting on a flannel draped over the ice box. It was usually infinitely refreshing, although this evening the frost hardly seemed to reach her tired, if not fried, nerve endings.

‘Did that have an effect on … on … the Exterminator, Mitya?’

‘I really don’t know, Galia. He was a delight as a toddler, I seem to recall. A cheeky, happy child – quite outgoing really. But ever since school age, well, seven or eight, he’s been very odd. I remember he was always pulling the wings off butterflies and cutting up caterpillars and snipping worms into pieces … and brusque with his fellow learners, terribly taciturn. I thought maybe he’d become a scientist, and I did try to push him in that direction when he was small, but alas, it was not to be.’

‘You taught him then, Vasya?’

‘No, not directly. He was in the school, but not my class, it was just …’ Vasya trailed off and contemplated the floor in silence for some moments, his face grim. Galia sighed and took in the vibrating, hairy moths circling the yellow kitchen lamp up above, and then glanced into the gloom under the table. Boroda was in her box, curled up, but not asleep: still trembling, and with her chocolate silk eyes wide open.

‘Poor dog, poor lapochka!’ muttered Galia, and rubbed the inside of her knees with each fist. She would be as stiff as a cadaver tomorrow. The clock in the bedroom struck midnight, and Galia longed for her pillow.

‘Galia, you must get that dog a collar.’ She was surprised by the sudden certainty in Vasya’s voice. He had finished with his shins, and now seemed determined to get his point across.

‘It’s not in the contract, Vasya,’ said Galia. ‘She’s my dog, but she’s not really my dog, if you see what I mean. We found each other. She chooses to live with me, so it doesn’t seem right to make her wear a collar. We choose to share our lives. We don’t need to display ownership. It’s not like …’ she hesitated slightly, ‘it’s not like we’re married, or bound in any way.’

‘Galia, yes, I accept that you are not married to your dog.’

Galia blushed and smiled slightly.

‘But you can’t go through tonight’s fiasco ever again, and neither can the dog. It’s monstrous. You must get Boroda a collar. You must take responsibility for her. It’s what civilized society insists, and there can be no argument.’

Galia wanted to argue, in fact she felt it was her duty to argue, and it was on the tip of her tongue to argue, but the battling words died in her throat and instead she took a slow sip of her tea. The day had been a trial for her, it was true. Difficult, for some reason, even before she had left the flat, even while she was cooking with all those irritating memories circling her for no reason. And then during the endless Elderly Club meeting she had felt uneasy, and not a little agitated. And after that the evening had become farcical, dangerous and threatening by turn, in a whirl of motorcycle wheels, dog’s teeth and mad old ladies with sickles in their hands.

In the end, it came down to this: she had stood on a point of principle, assuming that her fellow members of society would respect that principle, and she had come unstuck. Maybe it was time to give in, just a little, to make life safer. Maybe it was time to just get a collar and be done with it. It wouldn’t really hurt, would it?

‘But what if she bites me when I try to put it on? Or leaves home in disgust?’ asked Galia, with a teasing smile that showed a glimpse of her straight white teeth, and the gold ones that crowded round them.

‘She won’t bite you, and she won’t leave home. That dog has more sense than you give her credit for, Galia. She is your willing accomplice, and will respect your decision. You’re just being stubborn.’

Galia sighed. ‘Yes, Vasya, I admit it: maybe you’re right, on this occasion. There has been some stubbornness in this situation. I will get her a collar in the morning. But only if I find the time between the vegetable patch and the market.’

‘And a lead?’

‘A lead? Why would I want a lead?’ laughed Galia, the sound throaty and warm and quite unexpected to Vasya. ‘You go too far, Vasily Semyonovich!’

‘Why indeed? Of course, you won’t be taking her for walks or tying her up. She organises her own entertainment, I understand that. Oh well, maybe we can look at the issue of the lead next week, or next month. Towards autumn, perhaps?’ Now it was Vasya’s turn to trail off slightly as Galia fixed him with her steady blue gaze, and stopped laughing.

‘Well, all’s well that ends well, as they say!’ Vasya smiled and jerked his tea glass towards the light-fittings and moths in a toast. Galia leant away from the ice box and was about to stand to join in the toast when a sharp rap at the front door stopped her in mid-flow, hand raised, mouth open, eyes round.

‘Who’s that?’ she whispered. Boroda whined softly and stood up stiffly under the table, her claws stuttering slightly on the lino floor.

Vasya carefully propelled himself round on his stool with his long, spindly legs and peered out of the kitchen window into the warm, dark courtyard below. Once his eyes had adjusted to the depth of the gloom, he saw, lurking like a playground bully between the peeling swings and the weather-beaten chess tables, the unmistakable outline of a police car.

‘Galina Petrovna, I smell trouble,’ whispered Vasily, and pointed to the car with a nobbled finger.

There was another sharp rap at the door. This time the sound was harder, as if a baton, rather than a fist, was making contact.

‘Better let them in, my dear.’

‘I’ll let them in, in just a second. Boroda, get in the bedroom – in!’ Galia shooed the dog through the hall and into the bedroom, before gently sliding her inside the wardrobe, and behind a box of old photographs. She pushed the bedroom door to, and made her way stiffly across the hall. As she reached the threshold, the door vibrated in front of her eyes as more blows echoed through the quiet building. She took a deep breath, and slid back the bolts.

In the dim orange light of the hallway, she could make out two figures: one short and stocky, a dishevelled and obviously drunken policeman, and the other taller, younger, also dishevelled and smelling of sweat and dog crap. It was, of course, Mitya the Exterminator. His eyes were glassy, and they focused on a place somewhere behind her head. Behind the visitors, she perceived a number of grey heads popping out of other doors down the corridor, and then swiftly withdrawing at the sight of the representative of the law and his companion.

‘Citizens, I am sorry for the delay in opening the door, but it is very late. What can I do for you?’

‘Baba, Baba, don’t worry,’ cried the chubby policeman in a loud voice, wobbling slightly under the weight of his friendly words and leaning on the door jamb for support. ‘We know it’s late, but you’re welcome, very welcome … Do come in!’

Galia looked at him steadily and raised her eyebrows slowly. The policeman giggled and put a chubby fist into his mouth, realizing he had made some sort of mistake, but not quite able to work out what it was. The giggle gradually petered out, and he frowned instead, his glossy bottom lip protruding.

‘I warn you, be careful, Baba!’ he grimaced, fingering his gun holster with one clumsy hand and gesticulating towards his accomplice with the other. ‘Be careful, granny, he’s got teeth, this one. Oh, you – yes, you!’ here he pointed directly at Galia with a puffy finger, ‘need … to be careful! We all need to be careful!’ he giggled again, and leant against the wall more heavily, breathing hard. ‘Have you got any drink, Baba?’