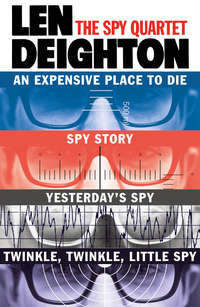

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

‘You are going into the cellars?’

‘Not the cellars of Datt’s place,’ Loiseau said to me. ‘We’re punching a hole in these cellars two doors away, then we’ll mousehole through into Datt’s cellars.’

‘Why didn’t you ask these people?’ I pointed at the house behind which the roadwork was going on. ‘Why not just ask them to let you through?’

‘I don’t work that way. As soon as I ask a favour I show my hand. I hate the idea of you knowing what we are doing. I may want to deny it tomorrow.’ He mopped his brow again. ‘In fact I’m damned sure I will be denying it tomorrow.’ Behind him the road-ripper exploded into action and the chiselled dust shone golden in the beams of the big lights, like illustrations for a fairy story, but from the damp soil came that sour aroma of death and bacteria that clings around a bombarded city.

‘Come along,’ said Loiseau. We passed three huge Berliot buses full of policemen. Most were dozing with their képis pulled forward over their eyes; a couple were eating crusty sandwiches and a few were smoking. They didn’t look at us as we passed by. They sat, muscles slack, eyes unseeing and minds unthinking, as experienced combat troops rest between battles.

Loiseau walked towards a fourth bus; the windows were of dark-blue glass and from its coachwork a thick cable curved towards the ground and snaked away into a manhole cover in the road. He ushered me up the steps past a sentry. Inside the bus was a brightly lit command centre. Two policemen sat operating radio and teleprinter links. At the back of the bus a large rack of MAT 49 sub-machine guns was guarded by a man who kept his silver-braided cap on to prove he was an officer.

Loiseau sat down behind a desk, produced a bottle of Calvados and two glasses. He poured a generous measure and pushed one across the desk to me. Loiseau sniffed at his own drink and sipped it tentatively. He drank a mouthful and turned to me. ‘We hit some old pavé just under the surface. The city engineer’s department didn’t know it was there. That’s what slowed us down, otherwise we’d be into the cellars by now, all ready for you.’

‘All ready for me,’ I repeated.

‘Yes,’ said Loiseau. ‘I want you to be the first into the house.’

‘Why?’

‘Lots of reasons. You know the layout there, you know what Datt looks like. You don’t look too much like a cop – especially when you open your mouth – and you can look after yourself. And if something’s going to happen to the first man in I’d rather it wasn’t one of my boys. It takes a long time to train one of my boys.’ He allowed himself a grim little smile.

‘What’s the real reason?’

Loiseau made a motion with the flattened hand. He dropped it between us like a shutter or screen. ‘I want you to make a phone call from inside the house. A clear call for the police that the operator at the Prefecture will enter in the log. We’ll be right behind you, of course, it’s just a matter of keeping the record straight.’

‘Crooked, you mean,’ I said. ‘It’s just a matter of keeping the record crooked.’

‘That depends where you are sitting,’ said Loiseau.

‘From where I’m sitting, I don’t feel much inclined to upset the Prefecture. The Renseignements généraux are there in that building and they include dossiers on us foreigners. When I make that phone call it will be entered on to my file and next time I ask for my carte de séjour they will want to deport me for immoral acts and goodness knows what else. I’ll never get another alien’s permit.’

‘Do what all other foreigners do,’ said Loiseau. ‘Take a second-class return ticket to Brussels every ninety days. There are foreigners who have lived here for twenty years who still do that rather than hang around for five hours at the Prefecture for a carte de séjour.’ He held his flat hand high as though shielding his eyes from the glare of the sun.

‘Very funny,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry,’ Loiseau said. ‘I couldn’t risk your telling the whole Prefecture that the Sûreté had enlisted you for a job.’ He smiled. ‘Just do a good job for me and I’ll make sure you have no trouble with the Prefecture.’

‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘And what if there is someone waiting for me at the other side of the mousehole? What if I have one of Datt’s guard dogs leap at my throat, jaws open wide? What happens then?’

Loiseau sucked his breath in mock terror. He paused. ‘Then you get torn to pieces,’ he said and laughed, and dropped his hand down abruptly like a guillotine.

‘What do you expect to find there?’ I asked. ‘Here you are with dozens of cops and noise and lights – do you think they won’t get nervous in the house?’

‘You think they will?’ Loiseau asked seriously.

‘Some will,’ I told him. ‘At least a few of the most sophisticated ones will suspect that something’s happening.’

‘Sophisticated ones?’

‘Come along, Loiseau,’ I said irritably. ‘There must be quite a lot of people close enough to your department to know the danger signals.’

He nodded and stared at me.

‘So that’s it,’ I said. ‘You were ordered to do it like this. Your department couldn’t issue a warning to its associates but it could at least warn them by handling things noisily.’

‘Darwin called it natural selection,’ said Loiseau. ‘The brightest ones will get away. You can probably guess my reaction, but at least I shall have the place closed down and may catch a few of the less imaginative clients. A little more Calvados.’ He poured it.

I didn’t agree to go, but Loiseau knew I would. The wrong side of Loiseau could be a very uncomfortable place to reside in Paris.

It was another half-hour before they had broken into the cellars under the alley and then it took twenty minutes more to mousehole through into Datt’s house. The final few demolitions had to be done brick by brick with a couple of men from a burglar-alarm company tapping around for wiring.

I had changed into police overalls before going through the final breakthrough. We were standing in the cellar of Datt’s next-door neighbour under the temporary lights that Loiseau’s men had slung out from the electric mains. The bare bulb was close to Loiseau’s face, his skin was wrinkled and grey with brick dust through which little rivers of perspiration were shining bright pink.

‘My assistant will be right behind you as far as you need cover. If the dogs go for you he will use the shotgun, but only if you are in real danger, for it will alert the whole house.’

Loiseau’s assistant nodded at me. His circular spectacle lenses flashed in the light of the bare bulb and reflected in them I could see two tiny Loiseaus and a few hundred glinting bottles of wine that were stacked behind me. He broke the breach of the shotgun and checked the cartridges even though he had only loaded the gun five minutes before.

‘Once you are into the house, give my assistant your overalls. Make sure you are unarmed and have no compromising papers on you, because once we come in you might well be taken into custody with the others and it’s always possible that one of my more zealous officers might search you. So if there’s anything in your pockets that would embarrass you …’

‘There’s a miniaturized radio transmitter inside my denture.’

‘Get rid of it.’

‘It was a joke.’

Loiseau grunted and said, ‘The switchboard at the Prefecture is being held open from now on’ – he checked his watch to be sure he was telling the truth – ‘so you’ll get through very quickly.’

‘You told the Prefecture?’ I asked. I knew that there was bitter rivalry between the two departments. It seemed unlikely that Loiseau would have confided in them.

‘Let’s say I have friends in the Signals Division,’ said Loiseau. ‘Your call will be monitored by us here in the command vehicle on our loop line.’9

‘I understand,’ I said.

‘Final wall going now,’ a voice called softly from the next cellar. Loiseau smacked me lightly on the back and I climbed through the small hole that his men had made in the wall. ‘Take this,’ he said. It was a silver pen, thick and clumsily made. ‘It’s a gas gun,’ explained Loiseau. ‘Use it at four metres or less but not closer than one, or it might damage the eyes. Pull the bolt back like this and let it go. The recess is the locking slot; that puts it on safety. But I don’t think you’d better keep it on safety.’

‘No,’ I said, ‘I’d hate it to be on safety.’ I stepped into the cellar and picked my way upstairs.

The door at the top of the service flight was disguised as a piece of panelling. Loiseau’s assistant followed me. He was supposed to have remained behind in the cellars but it wasn’t my job to reinforce Loiseau’s discipline. And anyway I could use a man with a shotgun.

I stepped out through the door.

One of my childhood books had a photo of a fly’s eye magnified fifteen thousand times. The enormous glass chandelier looked like that eye, glinting and clinking and unwinking above the great formal staircase. I walked across the mirror-like wooden floor feeling that the chandelier was watching me. I opened the tall gilded door and peered in. The wrestling ring had disappeared and so had the metal chairs; the salon was like the carefully arranged rooms of a museum: perfect yet lifeless. Every light in the place was shining bright, the mirrors repeated the nudes and nymphs of the gilded stucco and the painted panels.

I guessed that Loiseau’s men were moving up through the mouseholed cellars but I didn’t use the phone that was in the alcove in the hall. Instead I walked across the hall and up the stairs. The rooms that M. Datt used as offices – where I had been injected – were locked. I walked down the corridor trying the doors. They were all bedrooms. Most of them were unlocked; all of them were unoccupied. Most of the rooms were lavishly rococo with huge four-poster beds under brilliant silk canopies and four or five angled mirrors.

‘You’d better phone,’ said Loiseau’s assistant.

‘Once I phone the Prefecture will have this raid on record. I think we should find out a little more first.’

‘I think …’

‘Don’t tell me what you think or I’ll remind you that you’re supposed to have stayed down behind the wainscoting.’

‘Okay,’ he said. We both tiptoed up the small staircase that joined the first floor to the second. Loiseau’s men must be fretting by now. At the top of the flight of steps I put my head round the corner carefully. I put my head everywhere carefully, but I needn’t have been so cautious, the house was empty. ‘Get Loiseau up here,’ I said.

Loiseau’s men went all through the house, tapping panelling and trying to find secret doors. There were no documents or films. At first there seemed to be no secrets of any kind except that the whole place was a kind of secret: the strange cells with the awful torture instruments, rooms made like lush train compartments or Rolls Royce cars, and all kinds of bizarre environments for sexual intercourse, even beds.

The peep-holes and the closed-circuit TV were all designed for M. Datt and his ‘scientific methods’. I wondered what strange records he had amassed and where he had taken them, for M. Datt was nowhere to be found. Loiseau swore horribly. ‘Someone,’ he said, ‘must have told Monsieur Datt that we were coming.’

Loiseau had been in the house about ten minutes when he called his assistant. He called long and loud from two floors above. When we arrived he was crouched over a black metal device rather like an Egyptian mummy. It was the size and very roughly the shape of a human body. Loiseau had put cotton gloves on and he touched the object briefly.

‘The diagram of the Couzins girl,’ he demanded from his assistant.

It was obtained from somewhere, a paper pattern of Annie Couzins’s body marked in neat red ink to show the stab wounds, with the dimensions and depth written near each in tiny careful handwriting.

Loiseau opened the black metal case. ‘That’s it,’ he said. ‘Just what I thought.’ Inside the case, which was just large enough to hold a person, knife points were positioned exactly as indicated on the police diagram. Loiseau gave a lot of orders and suddenly the room was full of men with tape-measures, white powder and camera equipment. Loiseau stood back out of their way. ‘Iron maidens I think they call them,’ he said. ‘I seem to have read about them in some old schoolboy magazines.’

‘What made her get into the damn thing?’ I said.

‘You are naïve,’ said Loiseau. ‘When I was a young officer we had so many deaths from knife wounds in brothels that we put a policeman on the door in each one. Every customer was searched. Any weapons he carried were chalked for identity. When the men left they got them back. I’ll guarantee that not one got by that cop on the door but still the girls got stabbed, fatally sometimes.’

‘How did it happen?’

‘The girls – the prostitutes – smuggled them in. You’ll never understand women.’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Nor shall I,’ said Loiseau.

21

Saturday was sunny, the light bouncing and sparkling as it does only in impressionist paintings and Paris. The boulevard had been fitted with wall-to-wall sunshine and out of it came the smell of good bread and black tobacco. Even Loiseau was smiling. He came galloping up my stairs at 8.30 A.M. I was surprised; he had never visited me before, at least not when I was at home.

‘Don’t knock, come in.’ The radio was playing classical music from one of the pirate radio ships. I turned it off.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Loiseau.

‘Everyone’s at home to a policeman,’ I said, ‘in this country.’

‘Don’t be angry,’ said Loiseau. ‘I didn’t know you would be in a silk dressing-gown, feeding your canary. It’s very Noël Coward. If I described this scene as typically English, people would accuse me of exaggerating. You were talking to that canary,’ said Loiseau. ‘You were talking to it.’

‘I try out all my jokes on Joe,’ I said. ‘But don’t stand on ceremony, carry on ripping the place apart. What are you looking for this time?’

‘I’ve said I’m sorry. What more can I do?’

‘You could get out of my decrepit but very expensive apartment and stay out of my life. And you could stop putting your stubby peasant finger into my supply of coffee beans.’

‘I was hoping you’d offer me some. You have this very light roast that is very rare in France.’

‘I have a lot of things that are very rare in France.’

‘Like the freedom to tell a policeman to “scram”?’

‘Like that.’

‘Well, don’t exercise that freedom until we have had coffee together, even if you let me buy some downstairs.’

‘Oh boy! Now I know you are on the tap. A cop is really on the make when he wants to pick up the bill for a cup of coffee.’

‘I’ve had good news this morning.’

‘They are restoring public executions.’

‘On the contrary,’ said Loiseau, letting my remark roll off him. ‘There has been a small power struggle among the people from whom I take my orders and at present Datt’s friends are on the losing side. I have been authorized to find Datt and his film collection by any means I think fit.’

‘When does the armoured column leave? What’s the plan – helicopters and flame-throwers and the one that burns brightest must have been carrying the tin of film?’

‘You are too hard on the police methods in France. You think we could work with bobbies in pointed helmets carrying a wooden stick, but let me tell you, my friend, we wouldn’t last two minutes with such methods. I remember the gangs when I was just a child – my father was a policeman – and most of all I remember Corsica. There were bandits; organized, armed and almost in control of the island. They murdered gendarmes with impunity. They killed policemen and boasted of it openly in the bars. Finally we had to get rough; we sent in a few platoons of the Republican Guard and waged a minor war. Rough, perhaps, but there was no other way. The entire income from all the Paris brothels was at stake. They fought and used every dirty trick they knew. It was war.’

‘But you won the war.’

‘It was the very last war we won,’ Loiseau said bitterly. ‘Since then we’ve fought in Lebanon, Syria, Indo-China, Madagascar, Tunisia, Morocco, Suez and Algeria. Yes, that war in Corsica was the last one we won.’

‘Okay. So much for your problems; how do I fit into your plans?’

‘Just as I told you before; you are a foreigner and no one would think you were a policeman, you speak excellent French and you can look after yourself. What’s more you would not be the sort of man who would reveal where your instructions came from, not even under pressure.’

‘It sounds as though you think Datt still has a kick or two left in him.’

‘They have a kick or two left in them even when they are suspended in space with a rope around the neck. I never underestimate the people I’m dealing with, because they are usually killers when it comes to the finale. Any time I overlook that, it will be one of my policemen who takes the bullet in the head, not me. So I don’t overlook it, which means I have a tough, loyal, confident body of men under my command.’

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘So I locate Datt. What then?’

‘We can’t have another fiasco like last time. Now Datt will be more than ever prepared. I want all his records. I want them because they are a constant threat to a lot of people, including stupid people in the Government of my country. I want that film because I loathe blackmail and I loathe blackmailers – they are the filthiest section of the criminal cesspit.’

‘But so far there’s been no blackmail, has there?’

‘I’m not standing around waiting for the obvious to happen. I want that stuff destroyed. I don’t want to hear that it was destroyed. I want to destroy it myself.’

‘Suppose I don’t want anything to do with it?’

Loiseau splayed out his hands. ‘One,’ he said, grabbing one pudgy finger, ‘you are already involved. Two,’ he grabbed the next finger, ‘you are employed by some sort of British government department from what I can understand. They will be very angry if you turn down this chance of seeing the outcome of this affair.’

I suppose my expression changed.

‘Oh, it’s my business to know these things,’ said Loiseau. ‘Three. Maria has decided that you are trustworthy and in spite of her occasional lapses I have great regard for her judgement. She is, after all, an employee of the Sûreté.’

Loiseau grabbed his fourth digit but said nothing. He smiled. In most people a smile or a laugh can be a sign of embarrassment, a plea to break the tension. Loiseau’s smile was a calm, deliberate smile. ‘You are waiting for me to threaten you with what will happen if you don’t help me.’ He shrugged and smiled again. ‘Then you would turn my previous words about blackmail upon me and feel at ease in declining to help. But I won’t. You are free to do as you wish in this matter. I am a very unthreatening type.’

‘For a cop,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ agreed Loiseau, ‘a very unthreatening type for a cop.’ It was true.

‘Okay,’ I said after a long pause. ‘But don’t mistake my motives. Just to keep the record straight, I’m very fond of Maria.’

‘Can you really believe that would annoy me? You are so incredibly Victorian in these matters: so determined to play the game and keep a stiff upper lip and have the record straight. We do not do things that way in France; another man’s wife is fair game for all. Smoothness of tongue and nimbleness of foot are the trump cards; nobleness of mind is the joker.’

‘I prefer my way.’

Loiseau looked at me and smiled his slow, nerveless smile. ‘So do I,’ he said.

‘Loiseau,’ I said, watching him carefully, ‘this clinic of Datt’s: is it run by your Ministry?’

‘Don’t you start that too. He’s got half Paris thinking he’s running that place for us.’ The coffee was still hot. Loiseau got a bowl out of the cupboard and poured himself some. ‘He’s not connected with us,’ said Loiseau. ‘He’s a criminal, a criminal with good connections but still just a criminal.’

‘Loiseau,’ I said, ‘you can’t hold Byrd for the murder of the girl.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because he didn’t do it, that’s why not. I was at the clinic that day. I stood in the hall and watched the girl run through and die. I heard Datt say, “Get Byrd here.” It was a frame-up.’

Loiseau reached for his hat. ‘Good coffee,’ he said.

‘It was a frame-up. Byrd is innocent.’

‘So you say. But suppose Byrd had done the murder and Datt said that just for you to overhear? Suppose I told you that we know that Byrd was there? That would put this fellow Kuang in the clear, eh?’

‘It might,’ I said, ‘if I heard Byrd admit it. Will you arrange for me to see Byrd? That’s my condition for helping you.’ I expected Loiseau to protest but he nodded. ‘Agreed,’ he said. ‘I don’t know why you worry about him. He’s a criminal type if ever I saw one.’ I didn’t answer because I had a nasty idea that Loiseau was right.

‘Very well,’ said Loiseau. ‘The bird market at eleven A.M. tomorrow.’

‘It’s Sunday tomorrow,’ I said.

‘All the better, the Palais de Justice is quieter on Sunday.’ He smiled again. ‘Good coffee.’

‘That’s what they all say,’ I said.

22

A considerable portion of that large island in the Seine is occupied by the law in one shape or another. There’s the Prefecture and the courts, Municipal and Judicial police offices, cells for remand prisoners and a police canteen. On a weekday the stairs are crammed with black-gowned lawyers clutching plastic briefcases and scurrying like disturbed cockroaches. But on Sunday the Palais de Justice is silent. The prisoners sleep late and the offices are empty. The only movement is the thin stream of tourists who respectfully peer at the high vaulting of the Sainte Chapelle, clicking and wondering at its unparalleled beauty. Outside in the Place Louis Lépine a few hundred caged birds twitter in the sunshine and in the trees are wild birds attracted by the spilled seed and commotion. There are sprigs of millet, cuttlebone and bright new wooden cages, bells to ring, swings to swing on and mirrors to peck at. Old men run their shrivelled hands through the seeds, sniff them, discuss them and hold them up to the light as though they were fine vintage Burgundies.

The bird market was busy by the time I got there to meet Loiseau. I parked the car opposite the gates of the Palais de Justice and strolled through the market. The clock was striking eleven with a dull dented sound. Loiseau was standing in front of some cages marked ‘Caille reproductrice’. He waved as he saw me. ‘Just a moment,’ he said. He picked up a box marked ‘vitamine phospate’. He read the label: ‘Biscuits pour oiseaux’. ‘I’ll have that too,’ said Loiseau.

The woman behind the table said, ‘The mélange saxon is very good, it’s the most expensive, but it’s the best.’

‘Just half a litre,’ said Loiseau.

She weighed the seed, wrapped it carefully and tied the package. Loiseau said, ‘I didn’t see him.’

‘Why?’ I walked with him through the market.

‘He’s been moved. I can’t find out who authorized the move or where he’s gone to. The clerk in the records office said Lyon but that can’t be true.’ Loiseau stopped in front of an old pram full of green millet.

‘Why?’

Loiseau didn’t answer immediately. He picked up a sprig of millet and sniffed at it. ‘He’s been moved. Some top-level instructions. Perhaps they intend to bring him before some juge d’instruction who will do as he’s told. Or maybe they’ll keep him out of the way while they finish the enquêtes officieuses.’10

‘You don’t think they’ve moved him away to get him quietly sentenced?’

Loiseau waved to the old woman behind the stall. She shuffled slowly towards us.

‘I talk to you like an adult,’ Loiseau said. ‘You don’t really expect me to answer that, do you? A sprig.’ He turned and stared at me. ‘Better make it two sprigs,’ he said to the woman. ‘My friend’s canary wasn’t looking so healthy last time I saw it.’