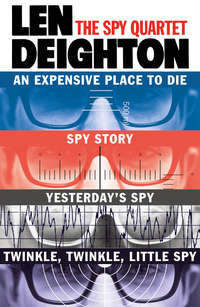

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

‘Ten out of ten,’ I said. ‘Good stuff: waiting till he took the glasses off. But you could use a better D and P man.’

‘They are just rough prints,’ said the courier. ‘The negs are half-frame but they are quite good.’

‘You are a regular secret agent,’ I said admiringly. ‘What did you do – shoot him in the ankle with the toe-cap gun, send out a signal to HQ on your tooth and play the whole thing back on your wristwatch?’

He rummaged through his papers again, then slapped a copy of L’Express upon the table top. Inside there was a photo of the US Ambassador greeting a group of American businessmen at Orly Airport. The courier looked up at me briefly.

‘Fifty per cent of this group of Americans work – or did work – for the Atomic Energy Commission. Most of the remainder are experts on atomic energy or some allied subject. Bertram: nuclear physics at MIT. Bestbridge: radiation sickness of 1961. Waldo: fall-out experiments and work at the Hiroshima hospital. Hudson: hydrogen research – now he works for the US Army.’ He marked Hudson’s face with his nail. It was the man he’d photographed.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘What are you trying to prove?’

‘Nothing. I’m just putting you in the picture. That’s what you wanted, isn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Thanks.’

‘I’m just juxtaposing a hydrogen expert from Peking with a hydrogen expert from the Pentagon. I’m wondering why they are both in the same city at the same time and especially why they both cross your path. It’s the sort of thing that makes me nervous.’ He gulped down the rest of his coffee.

‘You shouldn’t drink too much of that strong black coffee,’ I said. ‘It’ll be keeping you awake at night.’

The courier picked up his photos and copy of L’Express. ‘I’ve got a system for getting to sleep,’ he said. ‘I count reports I’ve filed.’

‘Watch resident agents jumping to conclusions,’ I said.

‘It’s not soporific.’ He got to his feet. ‘I’ve left the most important thing until last,’ he said.

‘Have you?’ I said, and wondered what was more important than the Chinese People’s Republic preparing for nuclear warfare.

‘The girl was ours.’

‘What girl was whose?’

‘The murdered girl was working for us, for the department.’

‘A floater?’

‘No. Permanent; warranty contract, the lot.’

‘Poor kid,’ I said. ‘Was she pumping Kuang-t’ien?’

‘It’s nothing that’s gone through the Embassy. They know nothing about her there.’

‘But you knew?’

‘Yes.’

‘You are playing both ends.’

‘Just like you.’

‘Not at all. I’m just London. The jobs I do for the Embassy are just favours. I can decline if I want to. What do London want me to do about this girl?’

He said, ‘She has an apartment on the left bank. Just check through her personal papers, her possessions. You know the sort of thing. It’s a long shot but you might find something. These are her keys – the department held duplicates for emergencies – small one for mail box, large ones front door and apartment door.’

‘You’re crazy. The police were probably turning it over within thirty minutes of her death.’

‘Of course they were. I’ve had the place under observation. That’s why I waited a bit before telling you. London is pretty certain that no one – not Loiseau nor Datt nor anyone – knew that the girl worked for us. It’s probable that they just made a routine search.’

‘If the girl was a permanent she wouldn’t leave anything lying around,’ I said.

‘Of course she wouldn’t. But there may be one or two little things that could embarrass us all …’ He looked around the grimy wallpaper of my room and pushed my ancient bedstead. It creaked.

‘Even the most careful employee is tempted to have something close at hand.’

‘That would be against orders.’

‘Safety comes above orders,’ he said. I shrugged my grudging agreement. ‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘Now you see why they want you to go. Go and probe around there as though it’s your room and you’ve just been killed. You might find something where anyone else would fail. There’s an insurance of about thirty thousand new francs if you find someone who you think should get it.’ He wrote the address on a slip of paper and put it on the table. ‘I’ll be in touch,’ he said. ‘Thanks for the coffee, it was very good.’

‘If I start serving instant coffee,’ I said, ‘perhaps I’ll get a little less work.’

16

The dead girl’s name was Annie Couzins. She was twenty-four and had lived in a new piece of speculative real estate not far from the Boul. Mich. The walls were close and the ceilings were low. What the accommodation agents described as a studio apartment was a cramped bed-sitting room. There were large cupboards containing a bath, a toilet and a clothes rack respectively. Most of the construction money had been devoted to an entrance hall lavished with plate glass, marble and bronze-coloured mirrors that made you look tanned and rested and slightly out of focus.

Had it been an old house or even a pretty one, then perhaps some memory of the dead girl would have remained there, but the room was empty, contemporary and pitiless. I examined the locks and hinges, probed the mattress and shoulder pads, rolled back the cheap carpet and put a knife blade between the floorboards. Nothing. Perfume, lingerie, bills, a postcard greeting from Nice, ‘… some of the swimsuits are divine …’, a book of dreams, six copies of Elle, laddered stockings, six medium-price dresses, eight and a half pairs of shoes, a good English wool overcoat, an expensive transistor radio tuned to France Musique, tin of Nescafé, tin of powdered milk, saccharine, a damaged handbag containing spilled powder and a broken mirror, a new saucepan. Nothing to show what she was, had been, feared, dreamed of or wanted.

The bell rang. There was a girl standing there. She may have been twenty-five but it was difficult to say. Big cities leave a mark. The eyes of city-dwellers scrutinize rather than see; they assess the value and the going-rate and try to separate the winners from the losers. That’s what this girl tried to do.

‘Are you from the police?’ she asked.

‘No. Are you?’

‘I’m Monique. I live next door in apartment number eleven.’

‘I’m Annie’s cousin, Pierre.’

‘You’ve got a funny accent. Are you a Belgian?’ She gave a little giggle as though being a Belgian was the funniest thing that could happen to anyone.

‘Half Belgian,’ I lied amiably.

‘I can usually tell. I’m very good with accents.’

‘You certainly are,’ I said admiringly. ‘Not many people detect that I’m half Belgian.’

‘Which half is Belgian?’

‘The front half.’

She giggled again. ‘Was your mother or your father Belgian, I mean.’

‘Mother. Father was a Parisian with a bicycle.’

She tried to peer into the flat over my shoulder. ‘I would invite you in for a cup of coffee,’ I said, ‘but I musn’t disturb anything.’

‘You’re hinting. You want me to invite you for coffee.’

‘Damned right I do.’ I eased the door closed. ‘I’ll be there in five minutes.’

I turned back to cover up my searching. I gave a last look to the ugly cramped little room. It was the way I’d go one day. There would be someone from the department making sure that I hadn’t left ‘one or two little things that could embarrass us all’. Goodbye, Annie, I thought. I didn’t know you but I know you now as well as anyone knows me. You won’t retire to a little tabac in Nice and get a monthly cheque from some phoney insurance company. No, you can be resident agent in hell, Annie, and your bosses will be sending directives from Heaven telling you to clarify your reports and reduce your expenses.

I went to apartment number eleven. Her room was like Annie’s: cheap gilt and film-star photos. A bath towel on the floor, ashtrays overflowing with red-marked butts, a plateful of garlic sausage that had curled up and died.

Monique had made the coffee by the time I got there. She’d poured boiling water on to milk powder and instant coffee and stirred it with a plastic spoon. She was a tough girl under the giggling exterior and she surveyed me carefully from behind fluttering eyelashes.

‘I thought you were a burglar,’ she said, ‘then I thought you were the police.’

‘And now?’

‘You’re Annie’s cousin Pierre. You’re anyone you want to be, from Charlemagne to Tin-Tin, it’s no business of mine, and you can’t hurt Annie.’

I took out my notecase and extracted a one-hundred-new-franc note. I put it on the low coffee table. She stared at me thinking it was some kind of sexual proposition.

‘Did you ever work with Annie at the clinic?’ I asked.

‘No.’

I placed another note down and repeated the question.

‘No,’ she said.

I put down a third note and watched her carefully. When she again said no I leaned forward and took her hand roughly. ‘Don’t no me,’ I said. ‘You think I came here without finding out first?’

She stared at me angrily. I kept hold of her hand. ‘Sometimes,’ she said grudgingly.

‘How many?’

‘Ten, perhaps twelve.’

‘That’s better,’ I said. I turned her hand over, pressed my fingers against the back of it to make her fingers open and slapped the three notes into her open palm. I let go of her and she leaned back out of reach, rubbing the back of her hand where I had held it. They were slim, bony hands with rosy knuckes that had known buckets of cold water and Marseilles soap. She didn’t like her hands. She put them inside things and behind them and hid them under her folded arms.

‘You bruised me,’ she complained.

‘Rub money on it.’

‘Ten, perhaps twelve, times,’ she admitted.

‘Tell me about the place. What went on there?’

‘You are from the police.’

‘I’ll do a deal with you, Monique. Slip me three hundred and I’ll tell you all about what I do.’

She smiled grimly. ‘Annie wanted an extra girl sometimes, just as a hostess … the money was useful.’

‘Did Annie have plenty of money?’

‘Plenty? I never knew anyone who had plenty. And even if they did it wouldn’t go very far in this town. She didn’t go to the bank in an armoured car if that’s what you mean.’ I didn’t say anything.

Monique continued, ‘She did all right but she was silly with it. She gave it to anyone who spun her a yarn. Her parents will miss her, so will Father Marconi; she was always giving to his collection for kids and missions and cripples. I told her over and over, she was silly with it. You’re not Annie’s cousin, but you throw too much money around to be the police.’

‘The men you met there. You were told to ask them things and to remember what they said.’

‘I didn’t go to bed with them …’

‘I don’t care if you took the anglais with them and dunked the gâteau sec, what were your instructions?’ She hesitated, and I placed five more one-hundred-franc notes on the table but kept my fingers on them.

‘Of course I made love to the men, just as Annie did, but they were all refined men. Men of taste and culture.’

‘Sure they were,’ I said. ‘Men of real taste and culture.’

‘It was done with tape recorders. There were two switches on the bedside lamps. I was told to get them talking about their work. So boring, men talking about their work, but are they ready to do it? My God they are.’

‘Did you ever handle the tapes?’

‘No, the recording machines were in some other part of the clinic.’ She eyed the money.

‘There’s more to it than that. Annie did more than that.’

‘Annie was a fool. Look where it got her. That’s where it will get me if I talk too much.’

‘I’m not interested in you,’ I said. ‘I’m only interested in Annie. What else did Annie do?’

‘She substituted the tapes. She changed them. Sometimes she made her own recordings.’

‘She took a machine into the house?’

‘Yes. It one of those little ones, about four hundred new francs they cost. She had it in her handbag. I found it there once when I was looking for her lipstick to borrow.’

‘What did Annie say about it?’

‘Nothing. I never told her. And I never opened her handbag again either. It was her business, nothing to do with me.’

‘The miniature recorder isn’t in her flat now.’

‘I didn’t pinch it.’

‘Then who do you think did?’

‘I told her not once. I told her a thousand times.’

‘What did you tell her?’

She pursed up her mouth in a gesture of contempt. ‘What do you think I told her, M. Annie’s cousin Pierre? I told her that to record conversations in such a house was a dangerous thing to do. In a house owned by people like those people.’

‘People like what people?’

‘In Paris one does not talk of such things, but it’s said that the Ministry of the Interior or the SDECE8 own the house to discover the indiscretions of foolish aliens.’ She gave a tough little sob, but recovered herself quickly.

‘You were fond of Annie?’

‘I never got on well with women until I got to know her. I was broke when I met her, at least I was down to only ten francs. I had run away from home. I was in the laundry asking them to split the order because I didn’t have enough to pay. The place where I lived had no running water. Annie lent me the money for the whole laundry bill – twenty francs – so that I had clean clothes while looking for a job. She gave me the first warm coat I ever had. She showed me how to put on my eyes. She listened to my stories and let me cry. She told me not to live the life that she had led, going from one man to another. She would have shared her last cigarette with a stranger. Yet she never asked me questions. Annie was an angel.’

‘It certainly sounds like it.’

‘Oh I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking that Annie and I were a couple of Lesbians.’

‘Some of my best lovers are Lesbians,’ I said.

Monique smiled. I thought she was going to cry all over me, but she sniffed and smiled. ‘I don’t know if we were or not,’ she said.

‘Does it matter?’

‘No, it doesn’t matter. Anything would be better than to have stayed in the place I was born. My parents are still there; it’s like living through a siege, besieged by the cost of necessities. They are careful how they use detergent, coffee is measured out. Rice, pasta and potatoes eke out tiny bits of meat. Bread is consumed, meat is revered and Kleenex tissues never afforded. Unnecessary lights are switched off immediately, they put on a sweater instead of the heating. In the same building families crowd into single rooms, rats chew enormous holes in the woodwork – there’s no food for them to chew on – and the w.c. is shared by three families and it usually doesn’t flush. The people who live at the top of the house have to walk down two flights to use a cold water tap. And yet in this same city I get taken out to dinner in three-star restaurants where the bill for two dinners would keep my parents for a year. At the Ritz a man friend of mine paid nine francs a day to them for looking after his dog. That’s just about half the pension my father gets for being blown up in the war. So when you people come snooping around here flashing your money and protecting the République Française’s rocket programme, atomic plants, supersonic bombers and nuclear submarines or whatever it is you’re protecting, don’t expect too much from my patriotism.’

She bit her lip and glared at me, daring me to contradict her, but I didn’t contradict. ‘It’s a lousy rotten town,’ I agreed.

‘And dangerous,’ she said.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Paris is all of those things.’

She laughed. ‘Paris is like me, cousin Pierre; it’s no longer young, and too dependent upon visitors who bring money. Paris is a woman with a little too much alcohol in her veins. She talks a little too loud and thinks she is young and gay. But she has smiled too often at strange men and the words “I love you” trip too easily from her tongue. The ensemble is chic and the paint is generously applied, but look closely and you’ll see the cracks showing through.’

She got to her feet, groped along the bedside table for a match and lit her cigarette with a hand that trembled very slightly. She turned back to me. ‘I saw the girls I knew taking advantage of offers that came from rich men they could never possibly love. I despised the girls and wondered how they could bring themselves to go to bed with such unattractive men. Well, now I know.’ The smoke was getting in her eyes. ‘It was fear. Fear of being a woman instead of a girl, a woman whose looks are slipping away rapidly, leaving her alone and unwanted in this vicious town.’ She was crying now and I stepped closer to her and touched her arm. For a moment she seemed about to let her head fall upon my shoulder, but I felt her body tense and unyielding. I took a business card from my top pocket and put it on the bedside table next to a box of chocolates. She pulled away from me irritably. ‘Just phone if you want to talk more,’ I said.

‘You’re English,’ she said suddenly. It must have been something in my accent or syntax. I nodded.

‘It will be strictly business,’ she said. ‘Cash payments.’

‘You don’t have to be so tough on yourself,’ I said. She said nothing.

‘And thanks,’ I said.

‘Get stuffed,’ said Monique.

17

First there came a small police van, its klaxon going. Co-operating with it was a blue-uniformed man on a motor-cycle. He kept his whistle in his mouth and blew repeatedly. Sometimes he was ahead of the van, sometimes behind it. He waved his right hand at the traffic as if by just the draught from it he could force the parked cars up on the pavement. The noise was deafening. The traffic ducked out of the way, some cars went willingly, some grudgingly, but after a couple of beeps on the whistle they crawled up on the stones, the pavement and over traffic islands like tortoises. Behind the van came the flying column: three long blue buses jammed with Garde Mobile men who stared at the cringing traffic with a bored look on their faces. At the rear of the column came a radio car. Loiseau watched them disappear down the Faubourg St Honoré. Soon the traffic began to move again. He turned away from the window and back to Maria. ‘Dangerous,’ pronounced Loiseau. ‘He’s playing a dangerous game. The girl is killed in his house, and Datt is pulling every political string he can find to prevent an investigation taking place. He’ll regret it.’ He got to his feet and walked across the room.

‘Sit down, darling,’ said Maria. ‘You are just wasting calories in getting annoyed.’

‘I’m not Datt’s boy,’ said Loiseau.

‘And no one will imagine that you are,’ said Maria. She wondered why Loiseau saw everything as a threat to his prestige.

‘The girl is entitled to an investigation,’ explained Loiseau. ‘That’s why I became a policeman. I believe in equality before the law. And now they are trying to tie my hands. It makes me furious.’

‘Don’t shout,’ said Maria. ‘What sort of effect do you imagine that has upon the people that work for you, hearing you shouting?’

‘You are right,’ said Loiseau. Maria loved him. It was when he capitulated so readily like that that she loved him so intensely. She wanted to care for him and advise him and make him the most successful policeman in the whole world. Maria said, ‘You are the finest policeman in the whole world.’

He smiled. ‘You mean with your help I could be.’ Maria shook her head. ‘Don’t argue,’ said Loiseau. ‘I know the workings of your mind by now.’

Maria smiled too. He did know. That was the awful thing about their marriage. They knew each other too well. To know all is to forgive nothing.

‘She was one of my girls,’ said Loiseau. Maria was surprised. Of course Loiseau had girls, he was no monk, but it surprised her to hear him talk like that to her. ‘One of them?’ She deliberately made her voice mocking.

‘Don’t be so bloody arch, Maria. I can’t stand you raising one eyebrow and adopting that patronizing tone. One of my girls.’ He said it slowly to make it easy for her to understand. He was so pompous that Maria almost giggled. ‘One of my girls, working for me as an informant.’

‘Don’t all the tarts do that?’

‘She wasn’t a tart, she was a highly intelligent girl giving us first-class information.’

‘Admit it, darling,’ Maria cooed, ‘you were a tiny bit infatuated with her.’ She raised an eyebrow quizzically.

‘You stupid cow,’ said Loiseau. ‘What’s the good of treating you like an intelligent human.’ Maria was shocked by the rusty-edged hatred that cut her. She had made a kind, almost loving remark. Of course the girl had fascinated Loiseau and had in turn been fascinated by him. The fact that it was true was proved by Loiseau’s anger. But did his anger have to be so bitter? Did he have to wound her to know if blood flowed through her veins?

Maria got to her feet. ‘I’ll go,’ she said. She remembered Loiseau once saying that Mozart was the only person who understood him. She had long since decided that that at least was true.

‘You said you wanted to ask me something.’

‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘Of course it matters. Sit down and tell me.’

She shook her head. ‘Another time.’

‘Do you have to treat me like a monster, just because I won’t play your womanly games?’

‘No,’ she said.

There was no need for Maria to feel sorry for Loiseau. He didn’t feel sorry for himself and seldom for anyone else. He had pulled the mechanism of their marriage apart and now looked at it as if it were a broken toy, wondering why it didn’t work. Poor Loiseau. My poor, poor, darling Loiseau. I at least can build again, but you don’t know what you did that killed us.

‘You’re crying, Maria. Forgive me. I’m so sorry.’

‘I’m not crying and you’re not sorry.’ She smiled at him. ‘Perhaps that’s always been our problem.’

Loiseau shook his head but it wasn’t a convincing denial.

Maria walked back towards the Faubourg St Honoré. Jean-Paul was at the wheel of her car.

‘He made you cry,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘The rotten swine.’

‘I made myself cry,’ said Maria.

Jean-Paul put his arm around her and held her tight. It was all over between her and Jean-Paul, but feeling his arm around her was like a shot of cognac. She stopped feeling sorry for herself and studied her make-up.

‘You look magnificent,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘I would like to take you away and make love to you.’

There was a time when that would have affected her, but she had long since decided that Jean-Paul seldom wanted to make love to anyone, although he did it often enough, heaven knows. But it was a good thing to hear when you have just argued with an ex-husband. She smiled at Jean-Paul and he took her hand in his large tanned one and turned it around like a bronze sculpture on a turntable. Then he released it and grabbed at the controls of the car. He wasn’t as good a driver as Maria was, but she preferred to be his passenger rather than drive herself. She lolled back and pretended that Jean-Paul was the capable tanned he-man that he looked. She watched the pedestrians, and intercepted the envious glances. They were a perfect picture of modern Paris: the flashy automobile, Jean-Paul’s relaxed good looks and expensive clothes, her own well-cared-for appearance – for she was as sexy now as she had ever been. She leaned her head close upon Jean-Paul’s shoulder. She could smell his after-shave perfume and the rich animal smell of the leather seats. Jean-Paul changed gear as they roared across the Place de la Concorde. She felt his arm muscles ripple against her cheek.

‘Did you ask him?’ asked Jean-Paul.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I couldn’t. He wasn’t in the right mood.’

‘He’s never in the right mood, Maria. And he’s never going to be. Loiseau knows what you want to ask him and he precipitates situations so that you never will ask him.’

‘Loiseau isn’t like that,’ said Maria. She had never thought of that. Loiseau was clever and subtle; perhaps it was true.