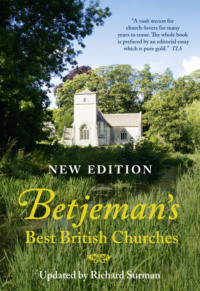

Betjeman’s Best British Churches

And carried to the work house ’gainst his will:

And being of this mortal life quite tired,

He lived about a month and then expired.

The other is on an outside monument on the north wall of the church at Harefield, near Uxbridge, one of the last three country villages left in Middlesex. It is to Robert Mossendew, servant of the Ashby family, who died in 1744. Had he been a gentleman his monument would at this time have been inside the church. He was a gamekeeper and is carved in relief with his gun above this inscription.

In frost and snow, thro’ hail and rain

He scour’d the woods, and trudg’d the plain;

The steady pointer leads the way,

Stands at the scent, then springs the prey;

The timorous birds from stubble rise,

With pinions stretch’d divide the skies;

The scatter’d lead pursues the sight

And death in thunder stops their flight;

His spaniel, of true English kind,

With gratitude inflames his mind;

This servant in an honest way,

In all his actions copies Tray.

The churchyard indeed often contains cruder but more lively and loving verses than the polished tributes inscribed in marble tablets within the church to squires and peers and divines of the county hierarchy. The Dartmoor parish of Buckland Monachorum displays this popular epitaph to a blacksmith which may be found in other parishes:

My sledge and hammer both declin’d,

My bellows too have lost their wind.

My fire’s extinct, my forge decay’d,

And in the dust my vice is laid,

My coal is spent, my iron’s gone,

My nails are drove, my work is done.

Though such an epitaph can scarcely be called Christian, it is at least not an attempt to cover up in mawkish sentiment or in crematorial good taste the inevitability of death.

The Outside

The church whose southern side we are approaching is probably little like the building which stood there even two centuries before, although it has not been rebuilt. The outside walls were probably plastered, unless the church is in a district where workable stone has long been used and it is faced with cut stone known as ashlar. Churches which are ashlar-faced all over are rare, but many have an ashlar-faced western tower, or aisle to the north-east or south-east, or a porch or transept built of cut stone in the 15th century by a rich family. Some have a guild chapel or private chantry where Mass was said for the souls of deceased members of the guild or family. This is usually ashlar-faced and has a carved parapet as well, and is in marked contrast with the humble masonry of the rest of the church.

Rubble or uneven flints were not considered beautiful to look at until the 19th century. People were ashamed of them and wished to see their churches smooth on the outside and inside walls, and weather-proof. At Barnack and Earl’s Barton the Saxons have even gone so far as to imitate in stone the decorative effects of wooden construction. Plaster made of a mixture of hair or straw and sand and lime was from Saxon times applied as a covering to the walls. Only the cut stone round the windows and doors was left, and even this was lime-washed. The plaster was thin and uneven. It was beautifully coloured a pale yellow or pink or white according to the tradition of the district. And if it has now been stripped off the church, it may still be seen on old cottages of the village if any survive. The earlier the walls of a church are, the less likely they are to be ashlar-faced, for there was no widespread use of cut stone in villages until the late 14th century when transport was better, and attention which had formerly been expended on abbeys was paid to building and enlarging parish churches.

EAST SHEFFORD: ST THOMAS – plaster on exterior walls would once have been common but is now a rarity; here too is a use of many materials: brick, stone, tile and timber

© Michael Ellis

And this is the place to say that most of the old parish churches in England are building rather than architecture. They are gradual growths, as their outside walls will shew; in their construction they partake of the character of cottages and barns and the early manor house, and not of the great abbey churches built for monks or secular canons. Their humble builders were inspired to copy what was to be seen in the nearest great church. The styles of Gothic came from these large buildings, but the village execution of them was later and could rarely rise to more than window tracery and roof timbering. Even these effects have a local flavour, they are a village voluntary compared with the music played on a great instrument by the cathedral organist. Of course here and there, when the abbeys declined, a famous mason from an abbey or cathedral might rebuild the church of his native place, and masons were employed in rich wool districts of East Anglia, the Midlands and parts of Yorkshire and Devon to build large churches which really are architecture and the product of a single brain, not the humble expression of a village community’s worship. Much has been discovered about the names and work of medieval architects by Mr John Harvey in his book Gothic England and in the researches of Messrs. Salzman, and Knoop and Jones.

These outside walls on which the sun shews up the mottled plaster, the sudden warm red of an 18th-century patching of brick, the gentle contrast with the ashlar, the lime-washed tracery of the windows, the heating chimney-stack in local brick climbing up the chancel wall or the stove pipe projecting from a window, these are more often seen today in old watercolours in the local museum, or in some affectionate and ill-executed painting hanging in the vestry shewing the church ‘before restoration in 1883’. Most of our old churches have been stripped of their plaster, some in living memory. The rubble has been exposed and then too often been repointed with grey cement, which is unyielding and instead of protecting the old stones causes them to crack and flake in frosty weather, for cement and stone have different rates of expansion. To make matters worse the cement itself has been snail pointed, that is to say pointed in hard, flat lines, so that the church wall looks like a crazy pavement.

Old paintings sometimes shew the external roofs as they used to be. The church roof and chancel are scarcely distinguishable from the cottage roofs. If the original steep pitch survives, it is seen to be covered with the local tiles, stones or thatch of the old houses of the district. 15th-century and Georgian raisings or lowerings of the roof and alterations to a flatter pitch generally meant a re-covering with lead, and the original pitch may be traced on the eastern face of the tower. Victorian restorers much enjoyed raising roofs to what they considered the original pitch, or putting on an altogether new roof in the cathedral manner. The effect of those re-roofings is generally the most obviously new feature on the outside of an old church. Red tiles and patterned slates from Wales or stone tiles which continually come down because they are set at a pitch too steep for their weight, are the usual materials. Instead of being graded in size, large at the eaves and getting smaller as they reach the ridge, the stone tiles are all of the same size so that the roof is not proportioned to the walls. The ridges are usually crowned with ridge tiles of an ornamental pattern which contrast in colour and texture with the rest. The gable ends are adorned with crosses. The drainage system is prominent and there will be pipes running down the wall to a gutter. On the rain-water heads at the top of these pipes there will probably be the date of the restoration. The old way of draining a roof was generally by leaden or wooden spouts rushing out of the fearsome mouths of gargoyles and carrying the water well beyond the walls of the church into the churchyard. If the water did drip on to the walls the plaster served as a protection from damp. Butterfield, a comparatively conservative and severely practical Victorian restorer, in his report on the restoration of Shottesbrooke church (1845) remarks of the flint walls of that elegant building, ‘There are no parapets to any part of the Church, and the water has continued to drip from the eaves for five centuries without any injury to the walls.’ On the other hand the water has continued to drip from the eaves of Sir Edwin Lutyens’ fine church of St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London, and over its Portland stone cornice with considerable injury to the brick walls in less than half a century. The nature of the wall surface, the pointing, and the means devised for draining the water clear from the wall foundation once it has reached the ground, have much to do with keeping out the damp.

Sometimes we may find on the outside walls a variety of scratches, marks and carvings. The only ones of any beauty will probably be the consecration crosses, where the Bishop anointed the walls with oil when the church was newly built. They are high up so that people would not brush them in going past. Similar crosses may be seen on stone altars inside the church. The small crosses which are cut roughly in the jambs of doorways were, according to the late E. A. Greening Lamborn, an angry antiquarian with a good prose style, probably put there not for consecration but ‘to scare away evil spirits and prevent them crossing the threshold’. There is a whole literature devoted to masons’ marks on the walls of churches, outside and in, and to the ‘scratch dials’ or ‘mass clocks’ which look like sundials lacking a gnomon, to be found on the outside south walls of many churches. The masons’ marks are triangles, diamonds, bent arrows, circles, squares and other shapes looking rather like boy scout signs, cut into ashlar in some churches, notably the large ones, and surviving where stone has not been re-tooled by the Victorians. Often they may be only scribbles. But they seem to help some antiquaries to give an exact date to buildings or portions of a building. Scratch dials or mass clocks were used generally to show the time when Mass was to be said (usually 9 a.m. in medieval England). Others are primitive clocks. But they, like the parish registers, belong to the non-visual side of church history and it is with the look of a church that this book is primarily concerned.

Finally there are on the outside of churches the gargoyles spouting water off the roof and the carved heads to be found either side of some windows and the figures in niches on tower or porch. Gargoyles can be fearsome, particularly on the north side of the church, and heads and statues, where they have survived Puritan outrage and Victorian zeal, are sometimes extremely beautiful or fantastic.

The church porch flapping with electoral rolls, notices of local acts, missionary appeals and church services (which will occupy us later) gives us a welcome. Though the powers of the parish vestry have been taken over by parish councils and local government, church doors or the porches which shelter them are often plastered with public announcements. Regularly will the village policeman nail to the church door some notice about Foot-and-Mouth Disease when the British Legion Notice Board has been denied him or the Post Office is shut. Most church porches in England are built on the south side, first as a protection for the door from prevailing south-west gales. Then they were used as places for baptism, bargains were made there, oaths sworn, and burial and marriage services conducted. Above some of them, from the 14th century onward, a room was built, usually for keeping parish chests and records. In these places many a village school was started. At first they may have been inhabited by a watchman, who could look down into the church from an internal window. In counties where stone is rare there are often elaborate wooden porches, notably in Sussex, Surrey and Essex.

ASHTON: ST JOHN THE BAPTIST – the 15th-century screens at the church have some of Devon’s best figurative panel painting

© Michael Ellis

Professor E. A. Freeman, the great Victorian ecclesiologist, thought little of a man who went up the churchyard path to the main door, which is more or less what we have done, and did not go round the whole building first. But he was an antiquary who took his churches slowly, speculated on them and did detective work about dates of extensions. On a day when the wind is not too cold and the grass not too long and wet, a walk round the outside of the church is always worth while. On the farther side, which is generally the north, there may well be extensions, a family mausoleum for instance, of which there is no sign inside the church beyond a blocked archway. Mr John Piper and I had a peculiar experience through not going round the outside of the derelict church of Wolfhamcote near Daventry in Warwickshire. The lovely building was locked, the windows smashed, and the sun was setting on its lichened stone. There was only one cottage near and we could make no one hear. So we climbed through a window in the south aisle. Bat-droppings were over rotting floors and damp stains on the ochre-plastered walls, and in the fading light we saw that the altar cloth had been raised and revealed a black tunnel with light at the end, a most peculiar thing to see beyond an altar. We approached and saw there were stairs going down under the table leading to a passage in which brass-studded coffins lay on shelves. When we went round the outside of the church we saw that beyond the east end was a Strawberry Hill Gothick extension, the mausoleum of the Tibbits family. Vestries are more usual on the north side of churches than mausolea, and very ugly most of them are, hard little stone sheds leant against the old walls. There will be almost for certain a north door blocked or bricked-up long ago, with the trace of its arch mouldings still there. There may even be a north porch. But unless the village and manor house are to the north of the church this side of the churchyard will be gloomy and its tombs will be, at the earliest, 19th century, except for a very few near the east end. And so round by the sexton’s tool-shed and the anthracite dump and the west door of the tower, we return to the south porch.

ROCK: ST PETER AND ST PAUL – like many churches, it has retained its Norman doorway while the church around it has been fully Gothicised

© Michael Ellis

Notice the stonework round the outside doors. Often it is round-headed and of Norman date, an elaborate affair of several concentric semi-circles of carved stone. It may even be the only Norman work left in the church and may originally have been the chancel arch before the chancel was enlarged and a screen put across its western end. The later medieval rebuilders respected the Norman craftsmanship and often kept a Norman door inside their elaborate porches.

There is often difficulty in opening the door. This gives the less impatient of us a chance of looking at the door itself. Either because the business of transferring the huge church lock was too difficult, or because here was a good piece of wood older than any of the trees in the parish, church doors have survived from the middle ages while the interiors on to which they open have been repaired out of recognition. The wood of the door may be carved or be decorated with old local ironwork. If it is an old door it will invariably open inwards. So first turn the iron handle and push hard. Then if the door seems to be locked, turn the handle the other way and push hard. Then feel on the wall-plate of the porch for the key. Church keys are usually six or eight inches long and easy to find. If there is no sign of the key and all vestry doors are locked, call at a house. If the path leading through the churchyard to a door in the vicarage wall is overgrown and looks unused, you may be sure the vicarage has been sold to wealthy unbelievers and there is no chance of getting the key from there. The houses to choose are those with pots of flowers in the window. Here will be living traditional villagers who even if they are chapel will probably know who it is who keeps the church key. Men are less likely to know than women, since men in villages are more rarely church-goers. Villagers are all out on Saturday afternoons shopping in the local town. Only an idiot and the dog remain behind.

The Porch and Bells

Down one step – for the churchyard will have risen round an old building – and we are in the church itself.

The practised eye can tell at a glance how severe the restoration has been, and often indeed who has done the damage. For instance almost every other church in Cornwall, beside many farther east, was restored by Mr J. P. St Aubyn late in the 19th century, and he has left his mark at the church porch in the form of a scraper of his own design, as practical and unattractive as his work. We must remember, however much we deplore it, that the most cumbersome bit of panelling bought from a Birmingham firm without regard for the old church into which it is to go, the sentimental picture for the Art Shop, the banner with the dislocated saint, the Benares ware altar vases, the brass commemorative tablet, the greenish stained-glass window with its sentimental Good Shepherd – often have been saved up for by some devout and penurious communicant. It must be admitted that spirituality and aesthetics rarely go together. ‘Carnal delight even in the holiest things,’ says Father R. M. Benson, founder of the Cowley Father ‘(habits of thought and philosophy, acquisition of knowledge, schemes of philanthropy, aesthetic propriety, influence in society) hinders the development of the Christ-life by strengthening the natural will.’ So when one is inclined to lament lack of taste and seemingly wilful destruction of beauty in a church, it is wise to remember that the incumbent, even if he be that rarity a man of aesthetic appreciation, is probably not to blame for modern blemishes to the fabric. He is primarily a missioner and he cannot offend his parishioners on so unspiritual a matter. The reader who casts his mind back to his early worship as a child will remember that a hymn board, or a brass cross or a garish window were, from his customary gazing on them Sunday after Sunday, part of his religious life. If as an older and more informed person his taste and knowledge tell him these things are cheap and hideous, he will still regret their passing with a part of him which is neither his intellect nor his learning. How much more will an uninformed villager, whose feeling always runs higher where the church is concerned than a townsman’s, cling to these objects he has known as a boy, however cheap they are. When the vicar or rector felt himself entitled to be a dictator, he could with more impunity and less offence than now, ‘restore’ the old church out of recognition. He could hack down the box-pews, re-erect a screen across the chancel, put the choir into surplices and move it from the west gallery to the chancel, and substitute a pipe organ for the old instruments. Even in those days many a disgruntled villager left the church to try his voice in chapel or to play his instrument in the old village band. It is a tribute to the hold of our church that congregations continued to use their churches after restorations in Victorian times. Perhaps the reason for the continued hold is that the more ritualistic performance of the Church Services made church more interesting. There is no doubt that Evangelicals were worried at the success of Tractarian methods. But picture your own childhood’s church whitewashed on the advice of the Diocesan Advisory Committee, your pew gone and a row of chairs in its place, the altar different, and the chancel cleared of choir-stalls and the choir non-existent as a consequence. Were it not your childhood’s church, you would consider this an improvement. One part of you may consider it an improvement despite associations, but not the other. Conservatism is innate in ecclesiastical arrangement. It is what saves for us the history of the village or town in wood and glass and metal and stone.

Let us enter the church by the tower door and climb to the ringing chamber where the ropes hang through holes in the roof. Nowhere outside England except for a very few towers in the rest of the British Isles, America and the Dominions, are bells rung so well. The carillons of the Netherlands and of Bourneville and Atkinson’s scent shop in London are not bell ringing as understood in England. Carillon ringing is done either by means of a cylinder worked on the barrel-organ and musical box principle, or by keyed notes played by a musician. Carillon bells are sounded by pulling the clapper to the rim of the bell. This is called chiming, and it is not ringing.

Bell ringing in England is known among ringers as ‘the exercise’, rather as the rearing and training of pigeons is known among the pigeon fraternity as ‘the fancy’. It is a class-less folk art which has survived in the church despite all arguments about doctrine and the diminution of congregations. In many a church when the parson opens with the words ‘Dearly beloved brethren, the Scripture moveth us in sundry places...’ one may hear the tramp of the ringers descending the newel stair into the refreshing silence of the graveyard. Though in some churches they may come in later by the main door and sit in the pew marked ‘Ringers Only’, in others they will not be seen again, the sweet melancholy notes of ‘the exercise’ floating out over the Sunday chimney-pots having been their contribution to the glory of God. So full of interest and technicality is the exercise that there is a weekly paper devoted to it called The Ringing World.

A belfry where ringers are keen has the used and admired look of a social club. There, above the little bit of looking-glass in which the ringers slick their hair and straighten their ties before stepping down into the outside world, you will find blackboards with gilded lettering proclaiming past peals rung for hours at a stretch. In another place will be the rules of the tower written in a clerkly hand. A charming Georgian ringers’ rhyme survives at St Endellion, Cornwall, on a board headed with a picture of ringers in knee-breeches:

We ring the Quick to Church and dead to Grave,

Good is our use, such usage let us have

Who here therefore doth Damn, or Curse or Swear,

Or strike in Quarrel thogh no Blood appear,

Who wears a Hatt or Spurr or turns a Bell

Or by unskilful handling spoils a Peal,

Shall Sixpense pay for every single Crime

’Twill make him careful ’gainst another time.

Let all in Love and Friendship hither come,

Whilst the shrill Treble calls to Thundering Tom,

And since bells are our modest Recreation

Let’s Rise and Ring and Fall to Admiration.

Many country towers have six bells. Not all these bells are medieval. Most were cast in the 17th, 18th or 19th centuries when change-ringing was becoming a country exercise. And the older bells will have been re-cast during that time, to bring them into tune with the new ones. They are likely to have been again re-cast in modern times, and the most ancient inscription preserved and welded on to the re-cast bell. Most counties have elaborately produced monographs about their church bells. The older bells have beautiful lettering sometimes, as at Somerby, and South Somercotes in Lincolnshire, where they are inscribed with initial letters decorated with figures so that they look like illuminated initials from old manuscripts interpreted in relief on metal. The English love for Our Lady survived in inscriptions on church bells long after the Reformation, as did the use of Latin. Many 18th- and even early 19th-century bells have Latin inscriptions. A rich collection of varied dates may be seen by struggling about on the wooden cage in which the bells hang among the bat-droppings in the tower.

Many local customs survive in the use of bells. In some places a curfew is rung every evening; in others a bell is rung at five in the morning during Lent. Fanciful legends have grown up about why they are rung, but their origins can generally be traced to the divine offices. The passing bell is rung differently from district to district. Sometimes the years of the deceased are tolled, sometimes the ringing is three strokes in succession followed by a pause. There are instances of the survival of prayers for the departed where the bell is tolled as soon as the news of the death of a parishioner reaches the incumbent.